Background

The number of individuals participating in athletic activities is continually increasing, whether these individuals are highly competitive athletes or weekend sports enthusiasts. [1, 2] Stress fractures of the femoral neck are uncommon injuries (see image depicted below). In general, these injuries occur in 2 distinct populations: (1) young, active individuals with unaccustomed strenuous activity or changes in activity, such as runners or endurance athletes, and (2) elderly individuals with osteoporosis. [3] Elderly individuals may also sustain femoral neck stress fractures; however, hip fractures are much more common and are often devastating injuries.

Femoral neck fractures in young patients are usually caused by high-energy trauma. These fractures are often associated with multiple injuries and high rates of avascular necrosis and nonunion. Results of this injury depend on (1) the extent of injury (ie, amount of displacement, amount of comminution, whether circulation has been disturbed), (2) the adequacy of the reduction, and (3) the adequacy of fixation. Recognition of the disabling complications of femoral neck fractures requires meticulous attention to detail in their management.

For excellent patient education resources, see eMedicineHealth's patient education article Total Hip Replacement.

Etiology

Training errors are the most common risk factors for femoral neck fractures, including a sudden increase in the quantity or intensity of training and the introduction of a new activity. Other factors include low bone density, abnormal body composition, dietary deficiencies, biomechanical abnormalities, and menstrual irregularities.

Predisposing factors, such as anatomic variations, relative osteopenia, poor physical conditioning, systemic medical conditions that demineralize bone, or temporary inactivity, can make bone more susceptible to stress fractures. As reported by Monteleone, studies have indicated that women have an increased incidence of stress fractures, which may be the result of anatomic variations. [4] Women tend to direct axial force during weight bearing along different axes of long bones compared with men. Women also have 25% less muscle mass per body weight than men. This may concentrate, rather than dissipate, the stabilizing forces through the bony anatomy.

Markey reported that Hersman et al documented women have a higher incidence of stress fractures. [5] This higher incidence is partly a result of mechanical differences and anatomic variations between men and women. Differences in women include various stride lengths, number of strides per distance, a wider pelvis, coxa vara, and genu valgum.

Exercise-induced endocrine abnormalities are well known to result in amenorrhea or nutritional deficiencies, which can lead to bone demineralization and can place these patients at risk for various overuse injuries. Stress fractures, especially in trabecular bone, have shown a decrease in bone mineral content. This decrease can be reproduced by a decrease in circulating estrogen, which is observed in amenorrheic female athletes. Lack of protective estrogen leads to a decrease in bone mass. The female athlete triad of amenorrhea, osteoporosis, and disordered eating affects many active women. Irreversible bone loss places the patient at a higher risk for fractures.

Most people are not competitive athletes and may not be at a level of optimum fitness. Individuals often force themselves to participate at a level for which they are not physically fit. Flexibility, muscle strength, and neuromuscular coordination contribute to injuries when individuals are not properly trained.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Stress fractures of the femoral neck are uncommon, but they may have serious consequences. Markey reported that femoral neck fractures comprise 5-10% of all stress fractures. [5] Certain groups of athletes, including long-distance runners who suddenly change or add activities, appear to have a higher prevalence of femoral neck stress fractures compared with the general population.

Plancher and Donshik reported a prevalence rate of at least 10% for ipsilateral femoral shaft fractures, of which 30% are missed on the initial presentation. [6] Brukner reported that women have a higher rate of stress fractures than men, with relative risks ranging from 1.2 to 10 for similar training volumes. [7] Training errors are the most common risk factors, including a sudden increase in the quantity or intensity of training and the introduction of a new activity.

A number of factors predispose the elderly population to fractures, including osteoporosis, malnutrition, decreased physical activity, impaired vision, neurologic disease, poor balance, and muscle atrophy. Hip fractures are common and are often devastating in the geriatric population. [8] More than 250,000 hip fractures occur in the United States each year; however, as reported by Koval and Zuckerman, with an aging population, the annual number of hip fractures is expected to double by the year 2050. [9]

Prevention of osteoporosis is key to reducing these numbers, as osteoporosis remains the single most important contributing factor to hip fractures. The prevalence of hip fractures, regardless of location, is highest among white women, followed by white men, black women, and black men.

Koval and Zuckerman noted the age-adjusted incidence of femoral neck fractures in the United States is 63.3 cases per 100,000 person-years for women and 27.7 cases per 100,000 person-years for men. [9] Femoral neck fractures in elderly patients occur most commonly after minor falls or twisting injuries, and they are more common in women. In addition, Joshi et al noted stress fractures of the ipsilateral femoral neck as a rare consequence of total knee arthroplasty. [10] Influencing factors are correction of a significant knee deformity and inactivity before the total knee arthroplasty.

International statistics

The exact incidence of femoral neck stress fractures is not known. Volpin et al reported a rate of 4.7% in 194 Israeli military recruits. [11] Zahger et al reported a higher rate of femoral neck stress fractures in Israeli female military recruits. [12] Insufficiency fractures are more common in females secondary to osteoporosis.

Functional Anatomy

The femoral aspect of the hip is made up of the femoral head with its articular cartilage and the femoral neck, which connects the head to the shaft in the region of the lesser and greater trochanters. The synovial membrane incorporates the entire femoral head and the anterior neck, but only the proximal half of the posterior neck. The shape and size of the femoral neck vary widely.

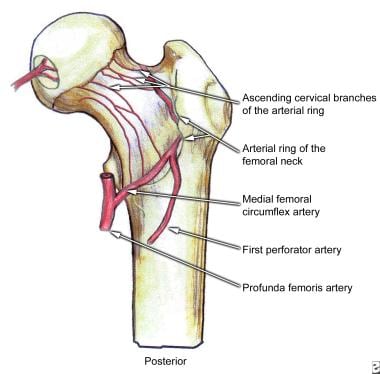

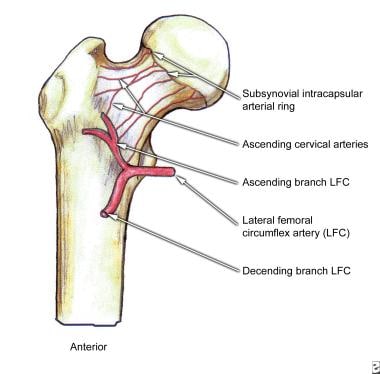

Crock standardized the nomenclature of the vessels around the base of the femoral neck. The blood supply to the proximal end of the femur is divided into 3 major groups. The first is the extracapsular arterial ring located at the base of the femoral neck. The second is the ascending cervical branches of the arterial ring on the surface of the femoral neck. The third is the arteries of the ligamentum teres.

A large branch of the medial femoral circumflex artery forms the extracapsular arterial ring posteriorly and anteriorly by a branch from the lateral femoral circumflex artery (see images shown below). The ascending cervical branches ascend on the surface on the femoral neck anteriorly along the intertrochanteric line. Posteriorly, the cervical branches run under the synovial reflection toward the rim of the articular cartilage, which demarcates the femoral neck from its head. The lateral vessels are the most vulnerable to injury in femoral neck fractures.

A second ring of vessels is formed as the ascending cervical vessels approach the articular margin of the femoral head. From this second ring of vessels, the epiphyseal arteries are formed. The lateral epiphyseal arterial group supplies the lateral weight-bearing portion of the femoral head. The epiphyseal vessels are joined by the inferior metaphyseal vessels and vessels from the ligamentum teres.

Femoral neck fractures frequently disrupt the blood supply to the femoral head (see images below). The superior retinacular and lateral epiphyseal vessels are the most important sources of this blood supply. Widely displaced intracapsular hip fractures tear the synovium and the surrounding vessels. The progressive disruption of the blood supply can lead to serious clinical conditions and complications, including osteonecrosis and nonunion.

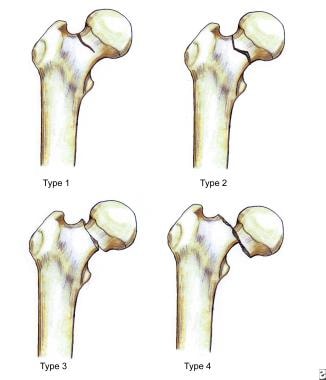

In 1961, Garden described the classification of femoral neck fractures. In this classification, femoral neck fractures are divided into the following 4 grades based on the degree of displacement of the fracture fragment:

-

Grade I is an incomplete or valgus impacted fracture.

-

Grade II is a complete fracture without bone displacement.

-

Grade III is a complete fracture with partial displacement of the fracture fragments.

-

Grade IV is a complete fracture with total displacement of the fracture fragments.

Frandersen et al concluded that clinically differentiating the 4 grades of fractures is difficult. Multiple observers were able to completely agree on the Garden classification in only 22% of the cases. Hence, classifying femoral neck fractures as nondisplaced (Garden grades I or II) or displaced (Garden grades III or IV) is more accurate. See the illustration depicted below.

Femoral neck fractures are usually intracapsular. The femoral neck has essentially no periosteal layer; hence, all healing is endosteal in origin. The synovial fluid bathing the fracture may interfere with the healing process. Angiogenic-inhibiting factors in synovial fluid can inhibit fracture repair. These factors, along with the precarious blood supply to the femoral head, make healing unpredictable and nonunions fairly frequent.

Bone physiology

Bone is a dynamic tissue, which continually reacts to stressful events. According to data from Maitra and Johnson, stress fractures result from an imbalance between bone resorption and bone deposition during the host bone response to repeated stressful events. [13] Most cortical stress involves tension or torsion; however, bone is weaker in tension and tends to fail by fracturing along a cement line.

Maitra and Johnson went on to report that tension forces promote osteoclastic resorption, whereas compressive forces promote an osteoblastic response. [13] With repeated stress, new bone formation cannot keep pace with bone resorption. This inability to keep up results in thinning and weakening of cortical bone, with propagation of cracks through cement lines, and, eventually, the development of microfractures. Without proper rest to correct this imbalance, these microfractures can progress to clinical fractures, the sine qua non of overuse.

A stress fracture is the result of a dynamic process over time, unlike an acute fracture, which is usually the result of a single supraphysiologic event. Markey reported that stress fractures can be described as a normal host response to abnormal stress, and this is different from insufficiency fractures, which are an abnormal host response to normal stresses. [5]

Devas, in 1965, classified stress fractures into 2 types that differ radiologically and have different clinical outcomes. [14] The first is the tension stress fracture, which results in a transverse fracture directed perpendicular to the line of force transmitted in the femoral neck and originates at the superior surface of the femoral neck. This fracture pattern is at increased risk for displacement. These fractures carry a risk for further advancement of the fracture line superiorly and eventual displacement, leading to nonunion and avascular necrosis. Hence, early diagnosis and treatment are essential.

The second type is a compression type of femoral neck stress fracture, which has evidence of internal callus formation on radiographic images. The fracture is usually located at the inferior margin of the femoral neck without cortical discontinuity. This fracture pattern is thought to be mechanically stable. The compression fracture occurs mostly in younger patients, and continued stress does not usually cause displacement. The earliest radiographic evidence of a compression stress fracture is usually a haze of internal callus in the inferior cortex of the femoral neck. Eventually, a small fracture line appears in this area, and it gradually scleroses.

Fullerton and Snowdy described a femoral neck stress fracture classification with the following 3 categories [15] : (1) tension, (2) compression, and (3) displaced, as depicted below. Tension fractures occur on the superolateral aspect of femoral neck and are at high risk for displacement. Compression fractures are similar to those described by Devas, which occur on the inferomedial aspect of the femoral neck and have a low risk for displacement.

Sport-Specific Biomechanics

Several theories have been developed to explain the mechanisms of femoral neck stress fractures and the biomechanics of the hip. Nordin and Frankel described the biomechanics of the hip. The load on the femoral neck can exceed 3-5 times the body weight when an individual is walking or running. Gravity acts on the center of the body mass, which results in torque on the medial aspect of the hip joint. This torque is counterbalanced by the contraction of the gluteus medius and minor. The total load on the femoral head is the sum of the forces producing these 2 torque forces. Then, these forces on the femoral head are transmitted through the femoral neck to the shaft, which create a significant amount of stress on the femoral neck as a result of compression and bending.

Minimal tension or compressive strains have been confirmed to occur in the superior aspect of the femoral neck during a normal single-leg stance. When tension increases, the inferior aspect of the femoral neck takes over the burden of damping the forces of compression. When a patient bends forward, stress is induced on the superior aspect of the femoral head; however, counter traction of the abductor muscles also occurs. Hence, if the gluteus medius muscle is fatigued, the strain is placed entirely on the superior aspect of the femoral neck. This strain can predispose patients to femoral neck stress fractures. If the abductor muscles fatigue and are unable to provide normal tension, the tensile stress in the femoral neck increases.

Muscle fatigue has been implicated as a contributing factor in the development of stress fractures. Muscle imbalance leads to changes in the application of stress across the femoral neck that may exceed the bone's capability to respond appropriately to stress. Muscle fatigue secondary to repetitive activity can decrease its shock-absorbing capacity so that higher peak stresses occur in the femoral neck. This can lead to gait abnormalities, which, in turn, can alter the body's center of gravity and change the patterns of stress placed on the femoral neck.

In the 1960s, Frankel proposed that femoral neck fractures occur in the presence of a high ratio of axial load to bending load. Altered muscle balance may also increase the risk of a hip fracture. Another theory is that a fall onto the hip with a direct blow to the greater trochanter may generate an axial force along the neck, creating an impaction fracture. The combination of axial and rotational forces has also been proposed as a mechanism.

The miserable malalignment syndrome combines femoral neck anteversion, genu valgum, increased Q-angle, tibia vera, and compensatory foot pronation that may not allow individuals to compensate for overuse. Leg-length discrepancy may also predispose individuals to injuries by creating an unequal distribution of stress and tension across the hip joint.

Prognosis

Depending on the nature of the fracture, the athlete may or may not return to premorbid functioning. A displaced stress fracture of the femoral neck may end the career of an elite athlete even if correctly treated. Early diagnosis and treatment may prevent displacement of the fracture and thus improve the prognosis.

Complications

Complications include recurrent stress fractures.

Patient Education

The patient with a femoral neck fracture should have a good understanding of his or her diagnosis and the benefits and risks of treatment. Completing education throughout the rehabilitation process is very important for patients to obtain the most optimal results and to possibly to return to their previous level of activity or specific sport.

Patients should take an active role in their care and understand what is necessary for proper healing, in addition to being instructed in a home exercise program for regaining their strength and range of motion of the affected lower extremity. Patient education is crucial to the prevention of recurrent neck stress fractures.

-

Posterior view of the extraosseous blood supply to the femoral head.

-

Anterior view of the extraosseous blood supply to the femoral head.

-

Garden fracture classification.

-

Classification of femoral neck stress fractures.