Practice Essentials

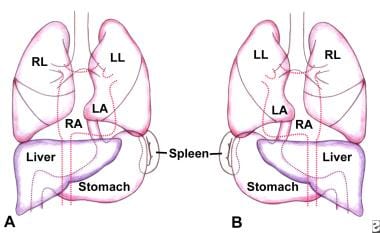

Marco Severino first recognized dextrocardia in 1643. More than a century later, Matthew Baillie described the complete mirror-image reversal of the thoracic and abdominal organs in situs inversus. Situs inversus is present in 0.01% of the population. Situs describes the position of the cardiac atria and viscera. Situs solitus is the normal position, and situs inversus is the mirror image of situs solitus (see the image below). Cardiac situs is determined by the atrial location. In situs inversus, the morphologic right atrium is on the left, and the morphologic left atrium is on the right. The normal pulmonary anatomy is also reversed, so that the left lung has 3 lobes and the right lung has 2 lobes. In addition, the liver and gallbladder are located on the left, whereas the spleen and stomach are located on the right. The remaining internal structures are also a mirror image of the normal.

When performing invasive surgical procedures, a mirror-image technique can be used that includes positioning the patient and equipment on the opposite side. However, most surgeons are right-handed, and operating instruments and pedals with their left hand and foot can be challenging. In cases of surgery, the surgeon has to modify port placements. There are many reports of surgical procedures in patients with situs inversus and the adaptations that need to be made. The surgical procedures include laparoscopic cholecystectomy, appendectomy, proximal gastric resection, gastrectomy for malignancies, nephrectomy, and various colorectal operations. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

Schematic drawings illustrate the standard anatomy of situs solitus (A) and the mirror image of situs inversus (B). The right lung (RL), left lung (LL), right atrium (RA), and left atrium (LA) are shown.

Schematic drawings illustrate the standard anatomy of situs solitus (A) and the mirror image of situs inversus (B). The right lung (RL), left lung (LL), right atrium (RA), and left atrium (LA) are shown.

Types of situs inversus

Situs inversus can be classified further into situs inversus with levocardia and situs inversus with dextrocardia. The classification of situs is independent of the cardiac apical position. The terms levocardia and dextrocardia indicate only the direction of the cardiac apex at birth; they do not imply the orientation of the cardiac chambers. In levocardia, the base-to-apex axis points to the left, and in dextrocardia, the axis is reversed. Isolated dextrocardia is also termed situs solitus with dextrocardia. The cardiac apex points to the right, but the viscera are otherwise in their usual positions. Situs inversus with dextrocardia is also termed situs inversus totalis because the cardiac position, as well as the atrial chambers and abdominal viscera, is a mirror image of the normal anatomy. Situs inversus totalis has an incidence of 1 in 8,000 births. Situs inversus with levocardia is less common, with an incidence of 1 in 22,000 births. [9]

When situs cannot be determined, the patient has situs ambiguous or heterotaxy. In these patients, the liver may be midline, the spleen absent or multiple, the atrial morphology unclear, and the bowel malrotated. Often, normally unilateral structures are duplicated or absent. The 2 primary subtypes of situs ambiguous include (1) right isomerism, or asplenia syndrome, and (2) left isomerism, or polysplenia syndrome. Heterotaxy syndromes have an incidence of 1 in 10,000 newborn births but account for about 4% of all cases of congenital heart disease (CHD). [9]

In classic right isomerism, or asplenia, bilateral right-sidedness occurs. These patients have bilateral right atria, a centrally located liver, and an absent spleen, and both lungs have 3 lobes. The descending aorta and inferior vena cava are on the same side of the spine. Right isomerism has an incidence of between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 20,000 births, male predominance, and a nearly 100% incidence of CHD. It often presents in childhood with a cyanotic heart defect such as a common AV canal, univentricular heart, transposition of the great arteries, or total anomalous pulmonary venous return. [9]

In left isomerism, or polysplenia, bilateral left-sidedness occurs. These patients have bilateral left atria and multiple spleens, and both lungs have 2 lobes. Interruption of the inferior vena cava with azygous or hemiazygous continuation is often present. Left isomerism has an incidence of between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 20,000 births and a female predominance. Associated cardiac malformations include partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, atrial septal defect (ASD), and a common atrioventricular (AV) canal. [9]

The features of situs ambiguous are inconsistent; therefore, situs ambiguous cases are challenging and require thorough evaluation of the viscera. [10] The location and relationships of the following should be reviewed carefully: abdominal viscera, hepatic veins, superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, coronary sinus, pulmonary veins, cardiac atria, atrioventricular connections and valves, cardiac ventricles, position of the cardiac apex, and aortic arch and great vessels.

Other features of situs inversus

Situs inversus occurs more commonly with dextrocardia. [11] A 3-5% incidence of congenital heart disease is observed in situs inversus with dextrocardia, usually with transposition of the great vessels. Of these patients, 80% have a right-sided aortic arch. Situs inversus with levocardia is rare, [12] and it is almost always associated with congenital heart disease. [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18]

The typical clinical phenotype of primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) includes any or all of the following: neonatal respiratory distress; chronic, persistent lower respiratory symptoms (early onset and persistent wet cough); chronic, persistent upper respiratory symptoms (nasal congestion and otitis media), and a laterality defect (situs inversus or ambiguous). The presence of any 2 of these features provides a strong clinical phenotype for PCD. At least 12% of PCD patients have situs ambiguous, and these patients have a 200-fold increased probability of having structural congenital heart disease as compared to the general population with heterotaxy. [19]

The recognition of situs inversus is important for preventing surgical mishaps that result from the failure to recognize reversed anatomy or an atypical history. For example, in a patient with situs inversus, cholecystitis typically causes left upper quadrant pain, and appendicitis causes left lower quadrant pain. A trauma patient with evidence of external trauma over the ninth to eleventh ribs on the right side is at risk for splenic injury. [20] If surgery is planned on the basis of radiographic findings in a patient with situs inversus, the surgeon should pay careful attention to image labeling to avoid errors such as a right thoracotomy for a left lung nodule.

Imaging modalities

Situs abnormalities may be recognized first by using radiography or ultrasonography. [10, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25] However, computed tomography (CT) scanning is the preferred examination for the definitive diagnosis of situs inversus with dextrocardia. CT scanning provides good anatomic detail for confirming visceral organ position, cardiac apical position, and great vessel branching. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually reserved for difficult cases or for patients with associated cardiac anomalies. [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] Most patients with situs inversus with levocardia require additional imaging to evaluate the associated cardiac anomalies. When radiation exposure is a concern, MRI or ultrasonography may be preferred. Prenatal MRI of the fetus can provide a detailed description of situs anomalies. [1]

The differential diagnosis includes appendicitis, asplenia/polysplenia, congenital coronary abnormalities, sinusitis, and ventricular septal defect. Other conditions to be considered are PCD, heterotaxy (see Heterotaxy Syndrome and Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia), left isomerism (ie, Ivemark syndrome) (see Asplenia/Polysplenia), right isomerism (ie, asplenia syndrome) (see Asplenia), situs solitus, and transposition of the great arteries.

If radiologic intervention is to be performed in a patient with situs inversus, the condition should be known from earlier diagnostic imaging. A question of improper image labeling must be resolved before any procedure is initiated. [31] Failure to recognize situs inversus before performing a radiologic procedure may result in intervention on the incorrect side of the patient. Attention to the left and right sides of the patient and the left and right labeling of images is helpful to prevent mistakes in diagnosis and/or surgical intervention.

Discordance between the direction of the cardiac apex and the abdominal situs suggests congenital heart disease. Situs ambiguous and situs inversus with levocardia have this discordance between the direction of the cardiac apex and the abdominal situs; thus, further imaging is usually needed.

Angiography is unnecessary for the diagnosis of situs inversus. In fact, noninvasive methods are preferred. Although the atrial morphology can be analyzed to determine atrial situs, angiography is usually reserved for the evaluation of congenital heart disease. The degree of confidence with angiography is high. The false-positive and false-negative angiographic findings are similar to those of fluoroscopy.

Radiography

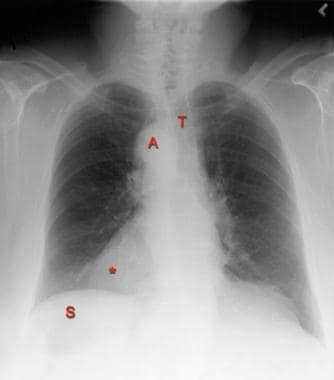

In most patients with situs inversus, chest radiography shows dextrocardia, with the cardiac apex pointing to the right and the aortic arch and stomach bubble located on the right as well.

(See the image below.)

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows that the cardiac apex (*) points to the right. A right-sided aortic arch (A) is associated with slight deviation of the trachea (T) to the left. The stomach (S) bubble is visible in the right upper quadrant.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows that the cardiac apex (*) points to the right. A right-sided aortic arch (A) is associated with slight deviation of the trachea (T) to the left. The stomach (S) bubble is visible in the right upper quadrant.

Confirming a mirror-image position of the atria allows confident diagnosis of situs inversus if the viscera are also reversed. The atrial morphology cannot be discerned on chest radiographs, but it can be determined indirectly by evaluating the bronchi. [24] In almost every patient, the side of the morphologic bronchus corresponds to the side of the morphologic atrium; therefore, situs inversus is confirmed if the bronchus intermedius is on the left, because the morphologic right atrium is also on the left. If a minor fissure can be identified, by inference, an eparterial bronchus and morphologic right atrium exist on that side.

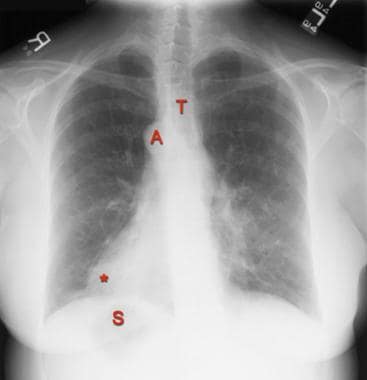

In situs inversus, the longer hyparterial bronchus is on the right side and passes under the pulmonary artery; the shorter eparterial bronchus is on the left side and passes over the pulmonary artery. A left bronchus and right bronchus of equal length suggests isomerism. Because 1 in 5 patients with situs inversus have Kartagener syndrome, evaluate the chest radiographs carefully for evidence of bronchiectasis (see the images below).

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 55-year-old woman with Kartagener syndrome and situs inversus. This image shows a right-sided aortic arch (A) with slight leftward deviation of the trachea (T), dextrocardia (*), and a stomach bubble (S) in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Subtle bronchiectasis is also present in the lung bases (see the next image).

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 55-year-old woman with Kartagener syndrome and situs inversus. This image shows a right-sided aortic arch (A) with slight leftward deviation of the trachea (T), dextrocardia (*), and a stomach bubble (S) in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Subtle bronchiectasis is also present in the lung bases (see the next image).

Magnified view of the left lower lobe in a 55-year-old woman with Kartagener syndrome and situs inversus (same patient as in previous image). This image shows bronchiectasis (arrows).

Magnified view of the left lower lobe in a 55-year-old woman with Kartagener syndrome and situs inversus (same patient as in previous image). This image shows bronchiectasis (arrows).

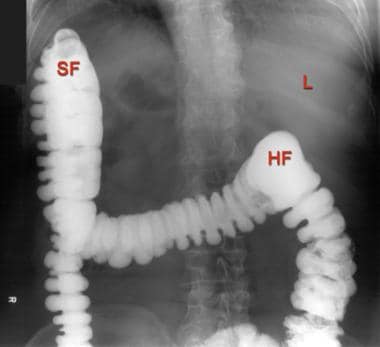

Upper and lower gastrointestinal examinations are usually not performed for the diagnosis of situs inversus. However, situs inversus may be found incidentally during such examinations. In an upper gastrointestinal examination in a patient with situs inversus, the stomach is on the right, with the C loop of the duodenum curving to the left. The liver and spleen are also in mirror-image locations compared to their normal position. In a barium enema examination, the sigmoid colon curves to the right, leading to a right-sided descending colon and terminating in a left-sided cecum (see the images below).

Radiograph of the upper abdomen from a barium enema examination in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows the liver (L) in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. The positions of the splenic flexure (SF) and hepatic flexure (HF) are reversed.

Radiograph of the upper abdomen from a barium enema examination in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows the liver (L) in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. The positions of the splenic flexure (SF) and hepatic flexure (HF) are reversed.

Radiograph of the lower abdomen from a barium enema examination in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows the sigmoid colon (SC) on the right and the cecum (C) on the left.

Radiograph of the lower abdomen from a barium enema examination in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows the sigmoid colon (SC) on the right and the cecum (C) on the left.

The degree of confidence of radiographs is high. CT scan findings can be used to resolve any remaining questions. The most common cause of false-positive results is the technologist's or radiologist's inattention to proper labeling. This problem occasionally occurs when a technologist prepares for posteroanterior imaging of the chest and labels the image, but the patient is then seated and imaged in an anteroposterior projection (eg, because of patient debility); as a result, the correct labeling is reversed.

The most common cause of a false-negative diagnosis of situs inversus also results from inattention to labeling. The technologist may incorrectly revise a properly labeled radiograph in a patient with situs inversus, because the anatomy is reversed compared to the normal anatomy. A radiologist may incorrectly display an image, so that it fits a mental template of what is normal without consciously noting the left or right marker. If a question of proper labeling exists, consult the technologist. If the projection of the image is known, the positioning of the name blocker can usually be used to reconstruct the correct labeling of the image. Alternatively, radiography may be repeated with supervision or special instructions to verify correct left-sided and right-sided labeling.

Most fluoroscopic machines have a button that electronically reverses the image. An experienced radiologist recognizes this reversal as soon as the table is moved to the left or right, because the expected direction of table travel is opposite to that observed on the image intensifier. An inexperienced operator can be confused by this apparent reversal of normal anatomy. Conceivably, a patient with situs inversus can be examined with a fluoroscopy machine, and the image can be reversed electronically in a misguided attempt to correct the mirror-image anatomy.

Computed Tomography

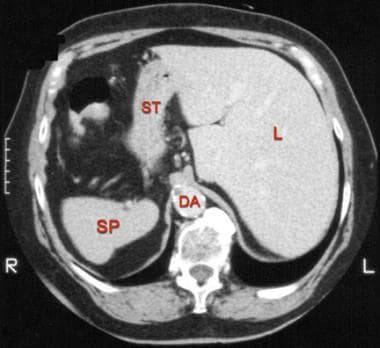

CT scanning demonstrates the mirror-image anatomy of the viscera in situs inversus (see the images below). The heart and great vessels are a mirror image of their normal anatomy; the left hemithorax contains a trilobed lung, whereas the right hemithorax contains a bilobed lung; and the liver and gallbladder are on the left side, whereas the spleen and stomach are on the right side. [30]

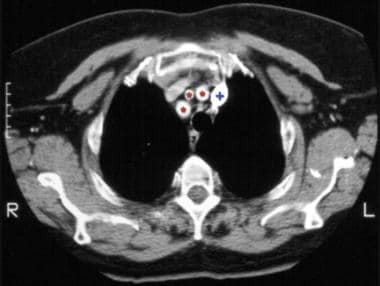

Chest computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the origins of the great vessels in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image demonstrates mirror-image branching of the great vessels (*) and a left-sided superior vena cava (+).

Chest computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the origins of the great vessels in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image demonstrates mirror-image branching of the great vessels (*) and a left-sided superior vena cava (+).

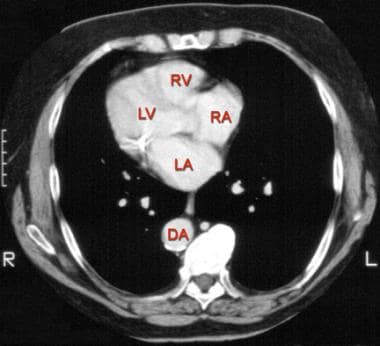

Chest computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the aortic outflow tract in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows reversal of the normal cardiac anatomy. The left atrium (LA), right atrium (RA), left ventricle (LV), and right ventricle (RV) are shown. The descending aorta (DA) is on the right.

Chest computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the aortic outflow tract in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows reversal of the normal cardiac anatomy. The left atrium (LA), right atrium (RA), left ventricle (LV), and right ventricle (RV) are shown. The descending aorta (DA) is on the right.

Computed tomography scan of the upper abdomen in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows reversal of the normal anatomy. The spleen (SP), stomach (ST), and liver (L) are shown. The descending aorta (DA) is on the right.

Computed tomography scan of the upper abdomen in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows reversal of the normal anatomy. The spleen (SP), stomach (ST), and liver (L) are shown. The descending aorta (DA) is on the right.

The degree of confidence with CT scanning is high. In preparing for CT scanning, the technologist records the patient's position—prone or supine—and whether the patient is moved into the scanner head first or feet first. If the orientation is specified incorrectly, the left-right orientation is displayed incorrectly, and situs inversus is simulated.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is a valuable adjunct to echocardiography and angiography in demonstrating abnormalities of congenital heart disease and in aiding surgical planning. This imaging modality is particularly helpful in diagnosing atrial situs. The morphologic right atrium contains the ostium of the coronary sinus; a connection to the suprahepatic inferior vena cava; a large, wide-based, pyramidal atrial appendage; the crista terminalis; and the pectinate muscles. The morphologic left atrium has the ostia for the pulmonary veins and an atrial appendage with a narrow base and a tubular, hooked shape. [29, 32]

The degree of confidence with MRI is high. As with CT scanning, if the technologist incorrectly records whether the patient is moved head first or feet first into the bore or whether the patient is prone or supine, the image is reversed, and incorrect situs anatomy is simulated.

Ultrasonography

Echocardiography demonstrates the morphologic left and right atria. The morphologic right atrium has connections to the superior and inferior vena cava and a wide atrial appendage. The morphologic left atrium has a narrow left atrial appendage. Ultrasonography demonstrates the mirror-image anatomy of the abdominal viscera. Fetal ultrasonography can be used to detect situs inversus in utero; detection of this condition in utero alerts the physician to the possibility of PCD or congenital heart disease, which then warrants further evaluation. [33]

The degree of confidence with ultrasonography is high. Although it is possible to switch the left and right sides of the ultrasonographic displays by holding the transducer backwards or electronically reversing the image, this error is expected only with inexperienced users. False-positive or false-negative diagnoses with ultrasonography are unlikely.

Nuclear Imaging

Any nuclear medicine study that is used to evaluate the heart or viscera can be influenced by the presence of situs inversus. These studies include cardiac, pulmonary, hepatobiliary, splenic, and gastrointestinal imaging. For example, on a ventilation-perfusion pulmonary scan, the photopenic defect from the heart is reversed in cases of situs inversus with dextrocardia. The technologist must be able to recognize situs inversus anatomy, because nonstandard camera positioning is often necessary for optimal imaging.

Pawar et al reported that changing patient positioning from feet-first supine during acquisition to prone during processing of rest perfusion and FDG-PET images resulted in images that were easier to interpret. [34]

The degree of confidence with most nuclear medicine studies is moderate because of the limited anatomic detail. Recording the anterior and posterior projections incorrectly reverses the left and right labeling. As with other digital images, the nuclear medicine image can be reversed electronically.

-

Schematic drawings illustrate the standard anatomy of situs solitus (A) and the mirror image of situs inversus (B). The right lung (RL), left lung (LL), right atrium (RA), and left atrium (LA) are shown.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows that the cardiac apex (*) points to the right. A right-sided aortic arch (A) is associated with slight deviation of the trachea (T) to the left. The stomach (S) bubble is visible in the right upper quadrant.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 55-year-old woman with Kartagener syndrome and situs inversus. This image shows a right-sided aortic arch (A) with slight leftward deviation of the trachea (T), dextrocardia (*), and a stomach bubble (S) in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Subtle bronchiectasis is also present in the lung bases (see the next image).

-

Magnified view of the left lower lobe in a 55-year-old woman with Kartagener syndrome and situs inversus (same patient as in previous image). This image shows bronchiectasis (arrows).

-

Radiograph of the upper abdomen from a barium enema examination in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows the liver (L) in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. The positions of the splenic flexure (SF) and hepatic flexure (HF) are reversed.

-

Radiograph of the lower abdomen from a barium enema examination in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows the sigmoid colon (SC) on the right and the cecum (C) on the left.

-

Chest computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the origins of the great vessels in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image demonstrates mirror-image branching of the great vessels (*) and a left-sided superior vena cava (+).

-

Chest computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the aortic outflow tract in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows reversal of the normal cardiac anatomy. The left atrium (LA), right atrium (RA), left ventricle (LV), and right ventricle (RV) are shown. The descending aorta (DA) is on the right.

-

Computed tomography scan of the upper abdomen in a 40-year-old man with situs inversus and dextrocardia. This image shows reversal of the normal anatomy. The spleen (SP), stomach (ST), and liver (L) are shown. The descending aorta (DA) is on the right.