Practice Essentials

Retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF) is characterized by the development of extensive fibrosis throughout the retroperitoneum, typically centered over the anterior surface of the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae, and results in entrapment and obstruction of retroperitoneal structures (notably the ureters). [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] In most patients (approximately 70%), no etiologic factor is found. Therefore, the term idiopathic RFP is used. [7, 8, 9]

Evidence suggests that RPF is an autoimmune response to an insoluble lipid called ceroid that has leaked through a thinned arterial wall from atheromatous plaques. [10, 11] Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis has been considered to be a spectrum of immunoglobulin G4-related disease, a systemic inflammatory disease. Studies have shown that most plasma cells are positive for immunoglobulin 4 (IgG4). The presence of IgG4-producing plasma cells suggests that RPF could be a manifestation of IgG4-related disease. [1, 7, 8, 12, 13, 4]

Other implicated causes include drugs, abdominal aortic aneurysm, ureteric renal injury, infection, retroperitoneal malignancy, postirradiation therapy, chemotherapy and hemilaminectomy, hypothyroidism, and carcinoid tumor. No genetic predominance is seen in malignant retroperitoneal fibrosis. [14, 15, 16, 17]

RPF can be diagnosed on the basis of the history and the radiologic observations. At times, the diagnosis is not established firmly until surgical exploration. The use of steroids in RPF remains controversial; however, some authors believe that steroids can be used as an adjuvant to surgical ureterolysis. Immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and tamoxifen, have been used to treat RPF. [18, 19, 20]

RPF must be differentiated from other conditions that can cause ureteric obstruction and renal failure, such as retroperitoneal abscess, infections, inflammation, pelvic surgery, and radiation therapy. Unusual causes that can cause ureteric obstruction include barium granuloma after colon perforation, use of sclerosing agents for treatment of inguinal hernia and hemorrhoids, and methyl methacrylate cement used for joint replacement. [21, 22, 23]

Imaging appearances similar to those of RPF can be demonstrated by abdominal aortic aneurysm; tumors inducing desmoplastic response, such as lymphomas, sarcomas, and pancreatic carcinomas; and metastatic malignancies from the breast, lung, stomach, colon, kidney, bladder, prostate, carcinoid and cervix. Other conditions that may simulate RPF include periaortic hematoma and amyloidosis.

(See the image below.)

Plain abdominal radiograph of a patient with biopsy-proven retroperitoneal fibrosis shows a calcified mass in the retroperitoneum (to the right of the mid lumbar spine).

Plain abdominal radiograph of a patient with biopsy-proven retroperitoneal fibrosis shows a calcified mass in the retroperitoneum (to the right of the mid lumbar spine).

Imaging modalities

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide superior delineation of the extent of the masses of RPF. [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] Plain radiographic findings in RPF are nonspecific, and most findings are related to the late complications of fibrosis, such as bowel obstruction and pulmonary edema secondary to renal failure. Contrast-enhanced studies, such as barium follow-through and barium enema examinations, can show the level of bowel obstruction. The diagnosis of RPF has often been suggested on the basis of the excretory urographic findings due to extensive changes in the urinary tract. Retrograde pyelography is used in patients with severely impaired renal function. [31, 32, 33]

Aortography, venography, and lymphangiography help in assessing the level and extent of occlusion; however, findings from these examinations can be normal in advanced disease.

Ultrasonography can be used as a noninvasive technique. Sonograms may or may not help in identifying the retroperitoneal mass, but they can readily demonstrate the degree of obstruction to the ureters and kidneys. Attempts have been made to differentiate benign RPF from malignant RPF by using color Doppler imaging.

Isotope renography is useful in the serial assessment of renal function. Gallium scintigraphy may demonstrate increased uptake, depending on the activity of inflammation. The use of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in differentiating benign from malignant RPF is promising. [34, 35, 36]

Limitations of techniques

Findings on plain radiography and contrast-enhanced studies are nonspecific, demonstrating the late effects of fibrosis. Excretory urography helps in establishing a diagnosis in the early stage of the disease.

Characteristically, medial deviation of the ureter is present, usually at the middle third, beginning at the level of the third or fourth lumbar vertebra. The medial deviation of the ureter is not a constant finding in patients with RPF, and approximately 20% of patients with normal urographic findings have medial deviation of ureters without demonstrable evidence of pathologic change in the urinary tract. Most retroperitoneal neoplasms displace the ureters in a lateral direction, but medial deviation can occur. Other causes for medial displacement of the ureters include aneurysm, metastatic tumors, and bladder diverticulum. Medial displacement may be seen after abdominoperineal resection and removal of pelvic malignancy.

Retrograde pyelography is an invasive technique with no additional value compared with excretory urography.

On sonograms, RPF may appear as a relatively echo-free mass centered on the sacral promontory. Imaging the retroperitoneum may not be possible, particularly in obese patients or in those with excessive bowel gas.

With CT and MRI, the fibrosis can be shown in more detail. The symmetric distribution and geometric shape are highly suggestive of RPF. CT scans may not be helpful in differentiating benign RPF from malignant RPF. MRI may help in differentiating the 2 conditions, but the diagnosis cannot be certain by using MRI.

Radiography

On plain abdominal radiographs, the psoas shadows may not be visible. The renal outline may be enlarged if hydronephrosis has occurred. Features related to the complications of RPF may be visualized; these include bowel dilatation due to obstruction and splenomegaly secondary to portal hypertension. Findings related to associated bone conditions may be seen. Such findings include metastasis, ankylosing spondylitis, and tuberculosis of the spine.

(See the image below.)

Plain abdominal radiograph of a patient with biopsy-proven retroperitoneal fibrosis shows a calcified mass in the retroperitoneum (to the right of the mid lumbar spine).

Plain abdominal radiograph of a patient with biopsy-proven retroperitoneal fibrosis shows a calcified mass in the retroperitoneum (to the right of the mid lumbar spine).

On chest radiographs, signs of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema may be seen secondary to fluid overload. Pulmonary fibrosis can occur if associated with SLE and ankylosing spondylitis. Mediastinal widening may occur due to a soft-tissue mass associated with mediastinal fibrosis.

Excretory urography

Characteristically, medial deviation of the ureters occurs, usually at the middle third, beginning at the level of third and fourth lumbar vertebrae. Varying degrees of ureteric obstruction with resultant hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and tapering of the ureter at the level of L4-L5 vertebrae may be evident. [37]

(See the images below.)

Excretory 5-minute urographic image demonstrates medial deviation of the right ureter at the L3-L4 vertebral level, which is suggestive of retroperitoneal fibrosis. Note the delayed excretion of the hydronephrotic left kidney.

Excretory 5-minute urographic image demonstrates medial deviation of the right ureter at the L3-L4 vertebral level, which is suggestive of retroperitoneal fibrosis. Note the delayed excretion of the hydronephrotic left kidney.

Excretory 15-minute urographic image shows progression in the severity of hydronephrosis. Smooth tapering of the medially deviated ureters is noted.

Excretory 15-minute urographic image shows progression in the severity of hydronephrosis. Smooth tapering of the medially deviated ureters is noted.

Excretory urogram in a 54-year-old man shows characteristic medial deviation of the ureter at the L4-L5 vertebral level. Note the lack of contrast material excretion on the left.

Excretory urogram in a 54-year-old man shows characteristic medial deviation of the ureter at the L4-L5 vertebral level. Note the lack of contrast material excretion on the left.

Retrograde pyeloureterography

Small ureteral catheters can be passed easily beyond the obstruction, despite the appearance of complete occlusion on excretory urograms, because of restricted peristalsis rather than intraluminal constriction.

Degree of confidence

Plain radiographic findings are nonspecific and occur in a variety of other conditions that are more common than RPF. Moreover, the findings are related to late effects or complications of the disease process rather than to the disease itself.

A diagnosis of RPF often is suggested on the basis of excretory urographic findings. Although excretory urography may be useful in showing the degree and level of obstruction in the ureters, it may not be particularly helpful in identifying the cause. Moreover, ureteric involvement and obstruction may not be seen in the early stage of the disease.

Retrograde studies are used to demonstrate the pelvocalyceal system and ureter when they are inadequate because of poor renal function and to assess the extent of the disease process.

Medial deviation of the ureter is not a constant finding in RPF, and approximately 20% of patients without RPF can have medial deviation. A minority of retroperitoneal neoplasms can also cause medial deviation of the ureter. Other conditions causing medial deviation of the ureters include aneurysm, metastatic tumor, and bladder diverticulum. Medial deviation can occur after abdominoperineal and pelvic malignancy resection.

On retrograde studies, the characteristic features of RPF are not a constant finding.

Computed Tomography

CT is the imaging modality used to diagnose RPF and to perform follow-up studies. RPF can be seen in detail on CT scans. The exact etiology cannot be identified, but it can be suggested by excluding other identifiable causes. CT scans help in assessing the extent of disease and in studying the effects on other organs. Differentiating benign RPF from malignant RPF may not be possible. [38, 25] Similar CT features may be seen in metastatic malignancy, lymphoma, periaortic hematoma, and amyloidosis. [23, 39]

On CT scans, RPF may appear as a rind of soft tissue around the aorta and inferior vena cava extending between the renal hilum and sacral promontory. Laterally, RPF spreads to involve the ureters, causing varying degrees of obstruction.

The fat plane between the mass and the psoas muscle may be obliterated. The mass tends not to displace the aorta anteriorly. The attenuation value of the mass is similar to that of muscle and shows variable degrees of enhancement depending on the stage of the disease.

Certain CT features can help in differentiating benign masses from malignant masses. The mass in RPF may be bulky but not as massive as neoplastic lesions; however, some exceptions exist. The presence of enlarged mesenteric nodes and displacement of the aorta from the spine by the periaortic mass favors malignancy, although some displacement can occur in RPF. Unlike RPF, most retroperitoneal neoplasms displace the ureters laterally.

RPF does not produce local bone destruction.

(See the images below.)

CT scan in a 62-year-old man shows a soft-tissue attenuating mass encircling the abdominal aorta. Note the extension of the soft-tissue mass around the left kidney. A right-sided nephrostomy and a left ureteric stent are seen.

CT scan in a 62-year-old man shows a soft-tissue attenuating mass encircling the abdominal aorta. Note the extension of the soft-tissue mass around the left kidney. A right-sided nephrostomy and a left ureteric stent are seen.

CT scan in a 62-year-old man shows a soft-tissue attenuating mass encircling the common iliac arteries.

CT scan in a 62-year-old man shows a soft-tissue attenuating mass encircling the common iliac arteries.

Nonenhanced transaxial CT scan of the abdomen in a 55-year-old man shows a well-defined, soft-tissue attenuating mass around the atheromatous abdominal aorta of normal caliber.

Nonenhanced transaxial CT scan of the abdomen in a 55-year-old man shows a well-defined, soft-tissue attenuating mass around the atheromatous abdominal aorta of normal caliber.

Contrast-enhanced transaxial CT scan in a 55-year-old man shows mild enhancement of a soft-tissue mass encircling the lower abdominal aorta.

Contrast-enhanced transaxial CT scan in a 55-year-old man shows mild enhancement of a soft-tissue mass encircling the lower abdominal aorta.

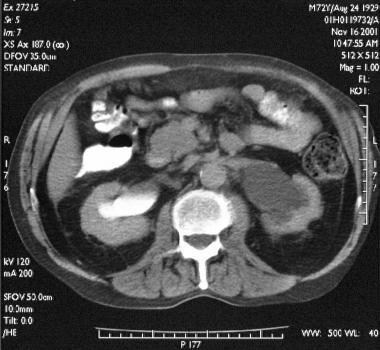

Transaxial enhanced abdominal CT scan in a 72-year-old man shows bilateral hydronephrosis that is more pronounced on the left than on the right.

Transaxial enhanced abdominal CT scan in a 72-year-old man shows bilateral hydronephrosis that is more pronounced on the left than on the right.

Transaxial contrast-enhanced CT scan through the lower abdomen in a 72-year-old man (same patient as in the previous image) shows a soft-tissue mass encasing the iliac vessel and ureters at the L5 vertebral level.

Transaxial contrast-enhanced CT scan through the lower abdomen in a 72-year-old man (same patient as in the previous image) shows a soft-tissue mass encasing the iliac vessel and ureters at the L5 vertebral level.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Retroperitoneal fibrosis appears as a mass with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and variable signal on T2-weighted images, depending on the activity of the disease. On T2-weighted images, RPF may appear hyperintense when active inflammation is present and hypointense in end-stage fibrosis. Inhomogeneous signal intensity on T2-weighted MRIs suggests malignancy. [24, 26, 27, 28]

The signal intensity of RPF is distinct from that of the adjacent fat and psoas muscle, thereby enabling adequate visualization of the lesion. MRI may help in assessing the response to treatment. After steroid therapy in the early stage of the disease, tissue edema is reduced and appears hypointense on T2-weighted sequences. Since the MR imaging features of most retroperitoneal soft-tissue masses are nonspecific, prediction of a specific histologic diagnosis remains a radiologic challenge. Nevertheless, there are some specific MRI appearances that are useful. Dynamic enhancement patterns can reflect the vascularity of masses, differentiating benign from malignant soft-tissue masses.

Brandt and associates evaluated dynamic enhancement analysis (DEA) as a possible predictor of response to medical treatment in idiopathic RPF. In this study, 24 patients with fibrosis were assessed by MRI and DEA. The dynamic enhancement quotient (DEQ) was measured before therapy with prednisone (n = 12) or tamoxifen (n = 12) and in follow-up investigations after 3 and 6 months. Response to medical treatment was recorded by changes in the retroperitoneal mass on MRI and possible relief of ureteral obstruction, which was monitored by intravenous pyelogram and/or mercaptoacetyltriglycine (MAG3) scan after removal of double-J stents. DEA was able to distinguish between patients with different response rates to medical treatment of idiopathic RPF and may be useful to individualize therapeutic decision-making. [40]

Most malignancies demonstrate high signal intensity on T2-weighted images; therefore, differentiating the early stage of RPF from malignancy may not be possible. Although the inhomogeneity of signal on T2-weighted sequences suggests malignancy, the diagnosis cannot be certain on the basis of MRI appearances alone.

Ultrasonography

On ultrasonograms, RPF may appear as a well-defined, smooth-marginated, hypoechoic, retroperitoneal soft-tissue mass encasing the aorta and inferior vena cava. Distal extension beyond the sacral promontory and the absence of lobulation suggest a benign etiology. Ultrasonography may demonstrate dilatation of the pelvocalyceal system and the ureters. Sonograms may show features of coexisting primary biliary cirrhosis, bile duct dilatation due to common bile duct stricture, portal hypertension due to portal vein compression, focal or diffuse pancreatic mass due to sclerosing pancreatitis, and dilated bowel loops due to obstruction.

Some have attempted to use Doppler ultrasonography to differentiate benign RPF from malignant RPF. However, findings suggest that color Doppler ultrasonography has no role in differentiating benign masses from malignant retroperitoneal masses.

Degree of confidence

Ultrasonography is a noninvasive technique that can be used to diagnose RPF and to perform follow-up studies. The detection of RPF with ultrasonography depends on the size of the periaortic soft tissue. Detecting RPF in the early stage may not be possible, and assessing the retroperitoneum may be difficult, particularly in obese patients or in those with a large amount of bowel gas.

Ultrasonography is not a sensitive examination, as compared with CT and MRI. Color Doppler imaging is not helpful in differentiating benign masses from malignant masses because they have no distinguishing features.

Ultrasonography is not the imaging modality used to assess RPF. Assessing the para-aortic region may be difficult, particularly in obese individuals, because of excessive retroperitoneal fat. Although features such as caudal extension beyond the sacral promontory and the absence of lobulation suggest a benign cause, malignancy cannot be excluded with confidence. Color Doppler imaging has no role in differentiating benign masses from malignant retroperitoneal masses.

Nuclear Imaging

In the early inflammatory stage of the disease, gallium-67 scintigraphy may show increased uptake. Little or no uptake may occur in the later stages of the disease. Therefore, gallium imaging may be helpful in predicting the therapeutic response to steroids and to monitor the response to treatment. The absence of gallium uptake in the mature stage of the disease makes the lesion less likely to be of malignant origin. Benign inflammation and malignancy can show increased uptake. [29, 34]

On FDG-PET scanning, benign RPF masses exhibit low uptake, whereas malignant masses exhibit increased uptake. [35, 36, 41] [42, 43, 44, 45] A study by Fernando et al of patients with RPF who underwent 101 FDG-PET scans showed that FDG-PET could reduce the need for biopsy in patients with RPF by distinguishing cancer from noncancerous RPF. It also appeared to predict a patient's response to steroids, which could help individualize treatment. Of the 24 patients with negative FDG-PET findings, none had malignancy on biopsy, and FDG-PET identified malignancy in 4 of 4 patients before biopsy. [43]

(See the image below.)

Analog (top) and digital (bottom) images of a radionuclide renogram show bilateral hydronephrosis with reduced function in the left kidney.

Analog (top) and digital (bottom) images of a radionuclide renogram show bilateral hydronephrosis with reduced function in the left kidney.

Angiography

Angiography and venography help in assessing the level and degree of obstruction. Abdominal aortic aneurysm can be demonstrated on angiograms.

Lymphangiographic findings in RPF include a delay in the passage of contrast material through the aortic and para-aortic lymphatics. Lymphatic flow may be obstructed at the L3-L4 vertebral level, resulting in nonvisualization of the lymphatics above the fourth lumbar vertebra, filling of collateral lymphatic channels, and small, irregular filling defects in the mesenteric and para-aortic lymph nodes. The absence of lymph node metastasis helps in excluding malignancy.

The retroperitoneal lymphatics are delicate structures; therefore, obstruction of the lymphatics occurs before compression of the ureters or major vessels.

Lymphangiography can be a complementary study. Lymphangiographic findings can be negative in patients with severe RPF. Angiography and venography are not helpful in the diagnosis of RPF. Angiography often leads to underestimation of the size of an aortic aneurysm because of the presence of a mural thrombus.

-

Plain abdominal radiograph of a patient with biopsy-proven retroperitoneal fibrosis shows a calcified mass in the retroperitoneum (to the right of the mid lumbar spine).

-

Excretory 5-minute urographic image demonstrates medial deviation of the right ureter at the L3-L4 vertebral level, which is suggestive of retroperitoneal fibrosis. Note the delayed excretion of the hydronephrotic left kidney.

-

Excretory 15-minute urographic image shows progression in the severity of hydronephrosis. Smooth tapering of the medially deviated ureters is noted.

-

Excretory urogram in a 54-year-old man shows characteristic medial deviation of the ureter at the L4-L5 vertebral level. Note the lack of contrast material excretion on the left.

-

Analog (top) and digital (bottom) images of a radionuclide renogram show bilateral hydronephrosis with reduced function in the left kidney.

-

Nephrostogram obtained after percutaneous nephrostomy shows smooth tapering of the ureter at the L4-L5 vertebral level.

-

CT scan in a 62-year-old man shows a soft-tissue attenuating mass encircling the abdominal aorta. Note the extension of the soft-tissue mass around the left kidney. A right-sided nephrostomy and a left ureteric stent are seen.

-

CT scan in a 62-year-old man shows a soft-tissue attenuating mass encircling the common iliac arteries.

-

Nonenhanced transaxial CT scan of the abdomen in a 55-year-old man shows a well-defined, soft-tissue attenuating mass around the atheromatous abdominal aorta of normal caliber.

-

Contrast-enhanced transaxial CT scan in a 55-year-old man shows mild enhancement of a soft-tissue mass encircling the lower abdominal aorta.

-

Transaxial enhanced abdominal CT scan in a 72-year-old man shows bilateral hydronephrosis that is more pronounced on the left than on the right.

-

Transaxial contrast-enhanced CT scan through the lower abdomen in a 72-year-old man (same patient as in the previous image) shows a soft-tissue mass encasing the iliac vessel and ureters at the L5 vertebral level.

-

Bilateral ureteric double-J stent in a patient with ureteric obstruction. Note the characteristic medial course of the right ureteric stent at the L4-L5 vertebral level.

-

Aortic and common iliac arterial graft in a patient with severe arterial insufficiency secondary to retroperitoneal fibrosis. Note a nephrostomy catheter in the right renal collecting system and the fragmented left ureteric stent.