Practice Essentials

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a serious gastrointestinal disease of neonates and is a leading cause of death and disability in preterm newborns. NEC is characterized by mucosal or transmucosal necrosis of part of the intestine. Infants born before term who are undersized and ill are most susceptible to NEC. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] NEC has an incidence of 3-15%, and in 30-40% of cases, surgical intervention is necessary. Mortality is 20-30%. [8] The high mortality in children with NEC is largely due to late diagnosis of early complications and the increasing survival of premature infants with extremely low birth weight who have severe NEC. [9] Early diagnosis through noninvasive imaging significantly improves outcomes.

The mainstay of diagnostic imaging is abdominal radiography. An anteroposterior (AP) abdominal radiograph and a left lateral decubitus radiograph (left-side down) are essential for initially evaluating any baby with abdominal signs. Characteristic findings on an AP abdominal radiograph include an abnormal gas pattern, dilated loops, and thickened bowel walls (suggesting edema/inflammation). Serial radiographs help assess disease progression. A fixed and dilated loop that persists over several examinations is especially worrisome. Pneumatosis intestinalis—gas in the bowel wall that displays a linear or bubbly pattern—is present in 50-75% of patients. It appears as a characteristic train-track lucency configuration within the bowel wall. Intramural air bubbles represent gas produced by bacteria within the wall of the bowel. [4, 10, 11, 12, 8, 13, 14, 15]

The presence of abdominal free air is ominous and usually requires emergency surgical intervention, but it can be difficult to discern on a flat radiograph, which is why decubitus radiographs are recommended at every evaluation. A subtle, oblong lucency over the liver and abdominal contents is characteristic of intraperitoneal air on a flat plate. It represents the air bubble that has risen to the most anterior aspect of the abdomen in a baby lying in a supine position.

Free air can be difficult to differentiate from intraluminal air. Left-side down (left lateral) decubitus radiography allows detection of intraperitoneal air, which rises above the liver shadow (right-side up) and can be visualized more easily than it can on other views. This view should be obtained with every AP examination until progressive disease is no longer a concern.

Portal gas appears as linear, branching areas of decreased density over the liver shadow and represents air present in the portal venous system. Its presence is considered to be a poor prognostic sign. Portal gas is much more dramatically observed on ultrasonography.

Distended loops of small bowel are one of the most common, although nonspecific, radiographic findings in NEC. Serial radiographic studies are important to monitor the degree of distention and to observe for any fixed or dilated loops of bowel persistent in nature and location for 24 hours.

Abdominal ultrasonography (AUS) studies of neonates with NEC have revealed positive findings. [16, 17] Ultrasonography of the abdomen characteristically shows thick-walled loops of bowel with hypomotility. Intraperitoneal fluid is often present. In the presence of pneumatosis intestinalis, gas is seen in the portal venous circulation within the liver. [18] Advantages of AUS include the availability at bedside and noninvasive imagery of intra-abdominal structures. Disadvantages of ultrasonography include limited availability at some medical centers, extensive training to discern subtle ultrasonographic appearance of some pathologies, and interference of abdominal air (easily observed on ultrasonography and in grossly distended patients) with assessing intra-abdominal structures. [7, 16, 17, 19, 20, 9, 21, 22]

AUS can depict bowel wall thickness and echogenicity, free and focal fluid collections, peristalsis, and the presence or absence of bowel wall perfusion using Doppler imaging without the need for ionizing radiation. [9, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 22, 28]

The use of CT is not advocated for the diagnosis of NEC or for identifying the presence of free air. CT scanning or an examination with a water-soluble enema may be used to demonstrate pneumatosis or a site of perforation.

(See the images below.)

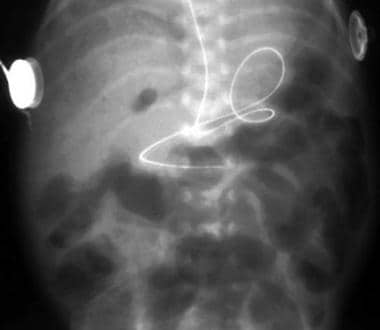

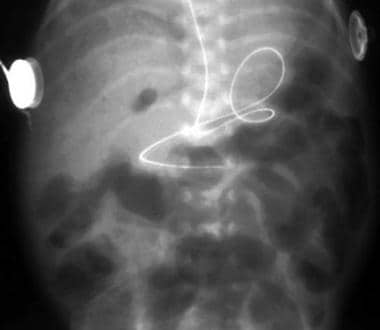

The radiograph demonstrates multiple dilated loops in the large bowel and small bowel. Note the pneumatosis intestinalis with bubbly and linear gas collections in the bowel wall.

The radiograph demonstrates multiple dilated loops in the large bowel and small bowel. Note the pneumatosis intestinalis with bubbly and linear gas collections in the bowel wall.

NEC staging

The Bell system is the staging system most commonly used to describe necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). [15, 29]

Bell stage I is suspected disease. Stage IA characteristics are as follows:

-

Mild, nonspecific systemic signs such as apnea, bradycardia, and temperature instability are present

-

Mild intestinal signs such as increased gastric residuals and mild abdominal distention are present

-

Radiographic findings can be normal or can show some mild nonspecific distention.

Stage IB diagnosis is the same as stage IA, with the addition of grossly bloody stool.

Bell stage II is definite disease. Stage IIA characteristics are as follows:

-

Patient is mildly ill.

-

Diagnostic signs include the mild systemic signs present in stage IA

-

Intestinal signs include all of the signs present in stage I, with the addition of absent bowel sounds and abdominal tenderness

-

Radiographic findings show ileus and/or pneumatosis intestinalis

Stage IIB characteristics are as follows:

-

Patient is moderately ill

-

Diagnosis requires all of stage I signs plus the systemic signs of moderate illness, such as mild metabolic acidosis and mild thrombocytopenia

-

Abdominal examination reveals definite tenderness, perhaps some erythema or other discoloration, and/or right lower quadrant mass

-

Radiographs show portal venous gas with or without ascites

Bell stage III is advanced disease. This stage represents advanced, severe NEC that has a high likelihood of progressing to surgical intervention. Stage IIIA characteristics are as follows:

-

Patient has severe NEC with an intact bowel

-

Diagnosis requires all of the above conditions, with the addition of hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory failure, severe metabolic acidosis, coagulopathy, and/or neutropenia

-

Abdominal examination shows marked distention with signs of generalized peritonitis

-

Radiographic examination reveals definitive evidence of ascites

Stage IIIB designation is reserved for the severely ill infant with perforated bowel observed on radiograph in addition to the findings for IIIA.

Radiography

Infants suspected of having NEC should undergo periodic radiography of the abdomen. In some centers, infants in whom NEC is highly suspected undergo routine frontal abdominal radiography every 4-6 hours.

Cross-table lateral examinations with a horizontal beam are useful for detecting subtle, early collections of free air, although some clinicians prefer to use lateral decubitus radiographs to detect free air (see the images below). In the presence of peritoneal adhesions, keeping the patient in the decubitus position for a prolonged period ensures that the air moves to the highest point.

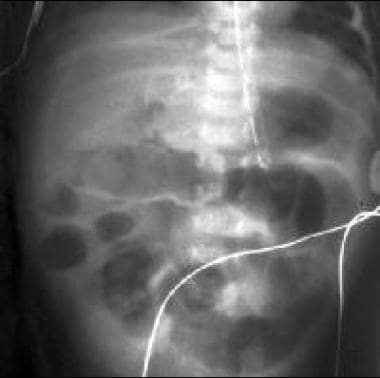

In this radiograph, free air is observed over the liver that outlines the falciform ligament. This finding indicates perforation of the bowel, which necessitates surgical exploration and resection of necrotic bowel.

In this radiograph, free air is observed over the liver that outlines the falciform ligament. This finding indicates perforation of the bowel, which necessitates surgical exploration and resection of necrotic bowel.

Imaging findings

Radiography is sufficient for an accurate diagnosis of NEC; the presence of air on a horizontal-beam radiograph is sufficient for diagnosing a bowel perforation.

Abdominal radiographs may demonstrate multiple dilated bowel loops that display little or no change in location and appearance with sequential studies. Pneumatosis intestinalis—gas in the bowel wall that displays a linear or bubbly pattern—is present in 50-75% of patients. (See the images below.)

The radiograph demonstrates multiple dilated loops in the large bowel and small bowel. Note the pneumatosis intestinalis with bubbly and linear gas collections in the bowel wall.

The radiograph demonstrates multiple dilated loops in the large bowel and small bowel. Note the pneumatosis intestinalis with bubbly and linear gas collections in the bowel wall.

Portal venous gas and gallbladder gas are indicative of serious disease. Pneumoperitoneum indicates a bowel perforation. (See the image below.)

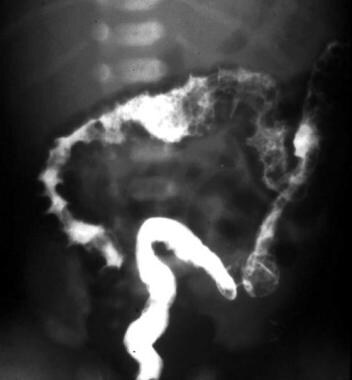

Computed tomography (CT) scanning or a water-soluble enema examination may be used to demonstrate pneumatosis or a site of perforation. (See the image below.)

Image obtained during examination with a water-soluble enema shows the pneumatosis well. This technique is not recommended.

Image obtained during examination with a water-soluble enema shows the pneumatosis well. This technique is not recommended.

A high index of suspicion is essential for the diagnosis of NEC. Although positive radiographic findings are predictive, negative findings do not rule out NEC. Both pneumatosis and portal venous gas are pathognomonic signs of NEC, but their absence or disappearance is not always a positive sign, and therefore improvement should always be assessed clinically. Dilated bowel loops on radiography are a nonspecific sign and may also be present in normal premature babies. True bowel wall thickening is rarely seen in NEC; the term separation of bowel loops is more appropriate and is nonspecific. [14]

Small amounts of free air may not be easily visible on supine abdominal radiographs. Thickening of the bowel wall may not be easily observed in the presence of a dilated bowel.

Abdominal USS is a useful adjunct to X-ray and can provide additional valuable information in patients with NEC.

In a study of preterm infants with NEC stage II or greater, plane abdominal radiography showed bowel loop distention on initial AR may serve as an additional diagnostic tool in the early diagnosis and severity of NEC stages II/III. In preterm infants with surgical NEC, there was a significant increase in the ratio of largest bowel loop diameter to the laterolateral diameter of the peduncle of the first lumbar vertebra (AD/L1 ratio) and the ratio of largest bowel loop diameter to the distance of the upper edge of the first lumbar vertebra and the lower edge of the second one, including the disc space (AD/L1-L2 ratio). [11]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography can be used to identify areas of loculation and/or abscess consistent with a walled-off perforation when patients with indolent NEC have scarce gas or a fixed area of radiographic density. Ultrasonography is also excellent for identifying and quantifying ascites. Serial examinations can be used to monitor the progression of ascites as a marker for the disease course. In addition, ultrasonography can be used to visualize portal air, which can easily be seen as bubbles present in the venous system. Abdominal ultrasonography has offers the ability to confirm findings of traditional radiographs (ie, pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous air) with the added ability to better assess the integrity of the intestinal walls, decreased peristalsis, and bowel wall perfusion. [19, 20, 23, 25, 22, 28]

Abdominal ultrasonography (AUS) can depict bowel wall thickness and echogenicity, free and focal fluid collections, peristalsis, and the presence or absence of bowel wall perfusion using Doppler imaging without the need for ionizing radiation. [9, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 22, 28]

Ultrasonographic assessment of major splanchnic vasculature can help differentiate NEC from other disorders that are either more benign or emergent. The orientation of the superior mesenteric artery in relationship to the superior mesenteric vein can provide information regarding the possibility of a malrotation with a subsequent volvulus. If a volvulus is present, the artery and vein are twisted and, at some point in their courses, their orientation switches. This abnormality can be detected, even if the rotation is 360⁰, if the full path of the vessels can be observed.

-

The radiograph demonstrates multiple dilated loops in the large bowel and small bowel. Note the pneumatosis intestinalis with bubbly and linear gas collections in the bowel wall.

-

Increasing pneumatosis intestinalis is seen in this radiograph.

-

Anteroposterior image shows necrotizing enterocolitis with pneumatosis intestinalis.

-

Lateral abdominal image shows pneumatosis intestinalis.

-

This radiograph shows free air secondary to bowel wall necrosis.

-

Left lateral decubitus radiograph shows free air.

-

Portal venous air is present in a patient with pneumatosis intestinalis.

-

Image obtained during examination with a water-soluble enema shows the pneumatosis well. This technique is not recommended.

-

In this radiograph, free air is observed over the liver that outlines the falciform ligament. This finding indicates perforation of the bowel, which necessitates surgical exploration and resection of necrotic bowel.