Practice Essentials

Gastric volvulus (Latin volvere, to roll) is rotation of all or part of the stomach by more than 180º, which may lead to a closed-loop obstruction and possible strangulation. [1, 2, 3] Symptoms may range from mild abdominal pain and vomiting, when no or partial outlet obstruction is present, to severe pain and retching, when there is complete obstruction and ischemia. [2] Presentations of gastric volvulus with severe chest pain mimicking acute coronary syndrome have been reported. [4, 5] Gastric volvulus is rare, and the diagnosis may be missed on imaging because it is not included in the differential diagnoses. Most cases of gastric volvulus are associated with paraesophageal hiatal hernia and thus should be considered in patients with acute abdominal symptoms and a history of hiatal hernia. [6, 7]

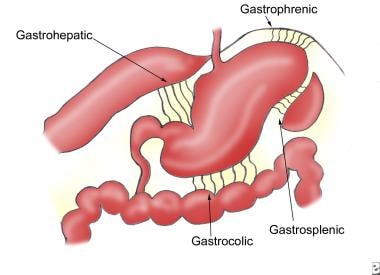

Idiopathic gastric volvulus, or type 1, makes up two thirds of cases and is presumably due to abnormal laxity of the gastrosplenic, gastroduodenal, gastrophrenic, and gastrohepatic ligaments. Type 2 is found in one third of patients and is usually associated with congenital or acquired abnormalities that result in abnormal mobility of the stomach. [8, 9, 10, 11]

The most frequently used classification for gastric volvulus is that created by Singleton, as follows [12] :

-

Organoaxial: This is the most common type of gastric volvulus, occurring in approximately 59% of cases, and is usually associated with diaphragmatic defects. The stomach rotates around an axis that connects the esophagogastric junction and the pylorus. The antrum rotates in the opposite direction to the fundus of the stomach. Strangulation and necrosis commonly occur.

-

Mesenteroaxial: This etiology accounts for approximately 29% of cases of gastric volvulus. The mesenteroaxial axis bisects the lesser and greater curvatures. The antrum rotates anteriorly and superiorly, so that the posterior surface of the stomach lies anteriorly.

-

Combined: The combined type of gastric volvulus is a rare form in which the stomach twists both mesenteroaxially and organoaxially.

(See the images below.)

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Imaging modalities

The definitive diagnosis of gastric volvulus resides with the radiologist. Typically, the first examination to be performed in the patient with symptoms referable to the chest and/or abdomen is a plain radiograph. Although this is a good examination to start with, the most definitive study is the upper GI barium study. [3, 13, 14, 15] Plain radiography may demonstrate findings that are indistinguishable from those that are produced by other causes of gastric atony or obstruction. However, the modality is useful for excluding other causes of the patient's symptoms, such as pneumoperitoneum or pneumothorax. [16]

Barium study is highly sensitive and specific. However, the diagnosis may be missed in cases of intermittent torsion. Fiberoptic endoscopy has a limited role in the diagnosis of gastric volvulus because the twist precludes passage of the endoscope. In a study by Ramos et of patients with gastric volvulus who had undergone preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE), the diagnostic yield was 34.6% (27/78). The most common endoscopic findings were erosive esophagitis (13/27) and gastric or duodenal ulcers (5/27). According to the authors, preoperative UGIE rarely demonstrates clinically significant findings and can potentially delay definitive surgical intervention. [17]

In a study by Mazaheri et al of 30 patients with surgically proven gastric volvulus who underwent preoperative CT, the most frequent and sensitive CT findings of volvulus with high positive likelihood ratios were stenosis at the hernia neck and transition point at the pylorus. The presence of perigastric fluid or a pleural effusion were significantly more frequent in patients with ischemia at surgical pathology. The transition point at the pylorus was the most sensitive (70–80%) and specific (100%) overall CT finding for the diagnosis of gastric volvulus. [9]

Laboratory studies are generally unrewarding, although levels of amylase and alkaline phosphatase may be increased.

Radiography

In mesenteroaxial volvulus, the distended stomach appears spherical on supine images. Two air-fluid levels are visible on the upright film: one in the fundus, which is inferior, and one in the antrum, which is superior. In addition, the upright image often demonstrates a beak where the esophagogastric junction is seen on normal images. If a nasogastric tube is passed, the esophagogastric junction is seen inferior to its normal location. If barium moves past the esophagogastric junction, the upside-down configuration of the stomach and the degree of obstruction can be documented.

Organoaxial volvulus is difficult to diagnose on plain images. The stomach lies horizontally and contains a single air-fluid level on upright views. No characteristic beak is observed. Decreased air is noted within the remaining GI tract. Barium study shows that the esophagogastric junction is lower than normal. Marked gastric dilatation and the slow passage of contrast material past the site of twisting are noted.

(See the images below for the radiographic characteristics of gastric volvulus.)

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with a typical beak (arrow). Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with a typical beak (arrow). Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

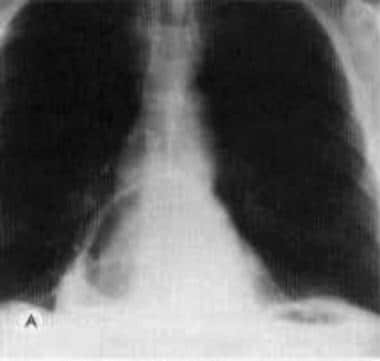

Frontal chest image shows 2 air-fluid levels, 1 below the left hemidiaphragm and 1 retrocardiac, in a patient with paraesophageal hiatal hernia complicated by gastric volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Frontal chest image shows 2 air-fluid levels, 1 below the left hemidiaphragm and 1 retrocardiac, in a patient with paraesophageal hiatal hernia complicated by gastric volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

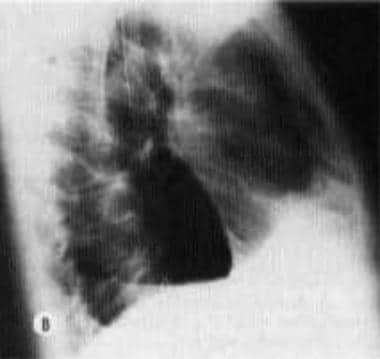

Lateral chest image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Lateral chest image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Frontal chest image obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images, 2 days later. An additional air-fluid level is present on the left side of the chest. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Frontal chest image obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images, 2 days later. An additional air-fluid level is present on the left side of the chest. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

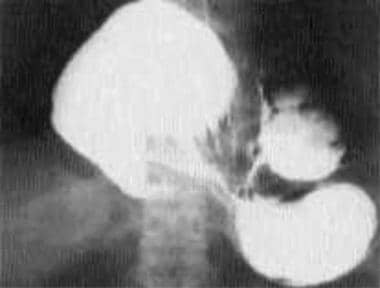

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series, obtained in the same patient as in the previous 3 images, shows a gastric volvulus with obstruction at the outlet of a rotated herniated segment. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series, obtained in the same patient as in the previous 3 images, shows a gastric volvulus with obstruction at the outlet of a rotated herniated segment. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

Computed Tomography

The computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of gastric volvulus can be variable. The extent of diaphragmatic herniation, the points of torsion, and the final position of the stomach determine the appearance. [18, 19, 8]

CT scanning and MRI are not typically considered to be the diagnostic examinations of choice in patients who are evaluated for gastric volvulus. However, some experts argue that the multiaxial reconstructions that are afforded by helical CT in particular may be preferred to the images obtained with conventional barium study, particularly in the acutely ill patient who is unable to tolerate a fluoroscopic examination. In addition, chronic gastric volvulus is often discovered incidentally in patients undergoing CT scanning for an unrelated condition. In most patients, CT scan or MRI findings that suggest a gastric volvulus should be confirmed with an upper GI series.

Without torsion, gastric volvulus may be difficult to distinguish from paraesophageal hiatal hernia, and false-positive, as well as false-negative, diagnoses can result.

In a study by Mazaheri et al of 30 patients with surgically proven gastric volvulus who underwent preoperative CT, the most frequent and sensitive CT findings of volvulus with high positive likelihood ratios were stenosis at the hernia neck and transition point at the pylorus. The presence of perigastric fluid or a pleural effusion were significantly more frequent in patients with ischemia at surgical pathology. The transition point at the pylorus was the most sensitive (70–80%) and specific (100%) overall CT finding for the diagnosis of gastric volvulus. [9]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is a noninvasive modality that can be performed on debilitated patients relatively easily and repeatedly; it requires no specific preparation. A study has demonstrated the peanut sign in a case of chronic gastric volvulus. The ultrasonographic features consist of a constricted segment of stomach, with 2 dilated segments located above and below the constricted part, akin to a peanut. [20] In several case reports, however, the ultrasonographic evaluation of gastric volvulus showed normal findings. Until more data are available, upper GI series should be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Nuclear Imaging

Gastric volvulus may be discovered during scintigraphic examination, sometimes incidentally, as the cause of a patient's symptoms. However, scintigraphic evidence of gastric volvulus should be confirmed with an upper GI series.

In one case report, a technetium-99m pertechnetate Meckel scan obtained to assess chronic GI bleeding in a child demonstrated an intrathoracic stomach with the greater curvature superior to the lesser curvature. Another case report demonstrated similar findings during an iodine-131 whole-body scan in a patient with metastatic thyroid cancer. In each case, upper GI series confirmed an organoaxial volvulus.

Angiography

During an episode of gastric volvulus, the arteries supplying the stomach are displaced according to the position of the stomach. Typically, the right and left gastroepiploic arteries are displaced high beneath the left hemidiaphragm. The right gastroduodenal artery also is displaced, and the left gastric artery appears to be coiled and shortened. Angiography is often used in the evaluation of massive or refractory GI hemorrhage. Although it is a rare cause of such hemorrhage, gastric volvulus should be considered. The angiographic appearance is sensitive and specific during an acute episode.

-

Normal ligamentous attachments of the stomach.

-

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Supine abdominal image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus with a typical beak (arrow). Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Upright abdominal image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images shows a mesenteroaxial volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Frontal chest image shows 2 air-fluid levels, 1 below the left hemidiaphragm and 1 retrocardiac, in a patient with paraesophageal hiatal hernia complicated by gastric volvulus. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Lateral chest image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Frontal chest image obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images, 2 days later. An additional air-fluid level is present on the left side of the chest. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.

-

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series, obtained in the same patient as in the previous 3 images, shows a gastric volvulus with obstruction at the outlet of a rotated herniated segment. Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Roentgenology, to be used only in the Medscape Reference Radiology article Gastric Volvulus.