Practice Essentials

Organizing pneumonia is characterized by the presence of granulation tissue in the distal air spaces. When organizing pneumonia is associated with granulation tissue in the bronchiolar lumen, the qualifying term bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) is added. A case of pulmonary disease may be classified as organizing pneumonia on the basis of the following criteria [1, 2] : (1) the cause has been determined, (2) the cause remains undetermined but is occurring in a specific and relevant context, (3) the disease is cryptogenic (idiopathic) organizing pneumonia (COP).

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is often confused with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP). [3] COP is a clinicopathologic syndrome that rapidly resolves with the use of corticosteroids but that is also marked by frequent relapses when treatment is tapered or stopped.

Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia is an inflammatory reaction with a variety of causes. Most cases are idiopathic. Swirls or plugs of fibrous, granulation tissue fil the small bronchiole airways. Although the term pneumonia is used, BOOP is not an infection. Causes of BOOP include radiation therapy; exposure to fumes or chemicals; postrespiratory infections; and medications. Disorders associated with BOOP include connective tissue disease, immunologic disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease. [4, 5, 6] Postradiotherapy BOOP in women has been reported to occur at a rate of 1-3%. [7]

Radiologically identical peripheral airspace consolidation occurs in patients with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) and BOOP. CEP primarily involves the upper lobe; by contrast, in BOOP, consolidation is predominantly in the lower zones, although some patients have pathologic characteristics of CEP and BOOP.

A variety of plain radiographic findings are found in patients with BOOP, although no radiographic features are diagnostic of the disease. Bilateral or unilateral, patchy alveolar airspace consolidation is seen; it is often subpleural and peribronchial in location and exists mainly in the lower zones.

Patients with COP present with nonspecific flulike symptoms (fever, cough) and mild to severe dyspnea. [8, 9] Severe dyspnea can be a sign of progressing disease. Crackles are a common finding on physical examination. Because of the lack of pathognomonic signs and symptoms, diagnosis is often delayed. [9, 10]

A tissue biopsy specimen is needed for a precise diagnosis, but clinicoradiologic characteristics determined through biopsy-based studies may provide enough diagnostic information. [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]

CT scanning is more sensitive than chest radiography in assessing disease pattern and distribution. CT scanning is also superior in determining the biopsy site; therefore, high-resolution CT (HRCT) is usually performed before lung biopsy.

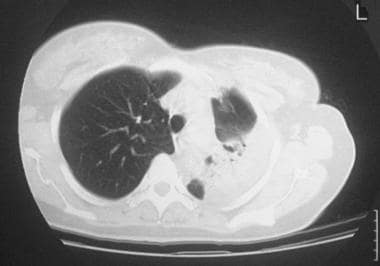

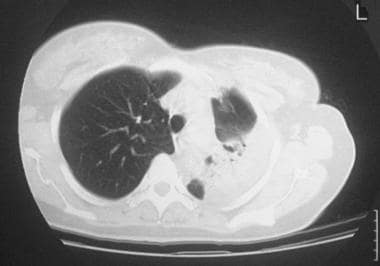

(See the image below.)

Standard nonenhanced axial thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows left lower-lobe consolidation with some loss of volume and an air bronchogram. Transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

Standard nonenhanced axial thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows left lower-lobe consolidation with some loss of volume and an air bronchogram. Transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

Manifestations of organizing pneumonia include the following [20, 21] :

-

Consolidation is the most common manifestation, seen in 80-95% of patients, and is usually bilateral and asymmetric.

-

Areas of ground-glass attenuation are present in 60-90% of patients and are bilateral and random in distribution.

-

The perilobular pattern is observed in about 55% of patients and consists of bowed or polygonal opacities with poorly defined margins around the interlobular septa. It occurs in all lung zones, with a predominance in middle and lower zones.

-

The reversed halo sign is a focal rounded area of ground-glass opacity surrounded by a ring of consolidation and is seen in about 20% of patients.

-

Nodular opacities (1-10 mm in diameter) are seen in 15-50% of patients and are randomly distributed but more numerous along the bronchovascular bundles.

Radiography

A variety of plain radiographic findings are found in patients with BOOP, although no radiographic features are diagnostic of the disease. Bilateral or unilateral, patchy alveolar airspace consolidation is seen; it is often subpleural and peribronchial in location and exists mainly in the lower zones. Consolidation is nonsegmental and is commonly 2-6 cm in diameter. An air bronchogram may be present. Nodules 3-5 mm in diameter are seen in approximately 50% of patients, and unilateral focal or lobar consolidation occurs in 5-31% of patients. [22] Basal, irregular linear opacities may be noted, and miliary shadowing has been reported. Cavitary BOOP that mimics tuberculosis and cavitating opacity after lung transplantation have also been reported.

(See the images below.) [23]

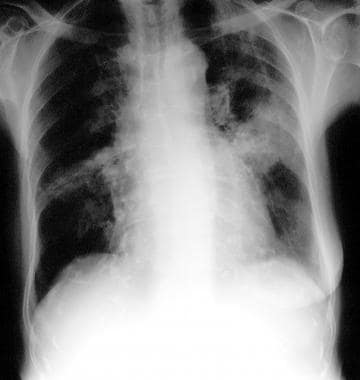

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause. The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. She presented with migratory lung opacities and areas of consolidation. Radiograph shows areas of consolidation at the lung base, with an air bronchogram at the right lung base. A wedge-shaped, pleural-based opacity is demonstrated astride the lateral part of the lesser fissure.

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause. The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. She presented with migratory lung opacities and areas of consolidation. Radiograph shows areas of consolidation at the lung base, with an air bronchogram at the right lung base. A wedge-shaped, pleural-based opacity is demonstrated astride the lateral part of the lesser fissure.

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause (same patient as in the previous image). The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. Radiograph obtained 2 months after the previous image shows that the consolidation had moved to the right upper zone and both midzones.

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause (same patient as in the previous image). The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. Radiograph obtained 2 months after the previous image shows that the consolidation had moved to the right upper zone and both midzones.

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause (same patient as in the previous 2 images). The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. Radiograph shows changing consolidation located in both midzones.

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause (same patient as in the previous 2 images). The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. Radiograph shows changing consolidation located in both midzones.

A 54-year-old man with asthma and an 8- to 9-month history of left-sided chest pain, anorexia, weight loss, and increasing shortness of breath. The patient had an episode of pneumonia 6 months previously, when a chest radiograph showed a right-sided, apical, segmental consolidation, which improved with antimicrobial therapy. This radiograph shows opacity in the left upper zone, with tethering to the pleural space.

A 54-year-old man with asthma and an 8- to 9-month history of left-sided chest pain, anorexia, weight loss, and increasing shortness of breath. The patient had an episode of pneumonia 6 months previously, when a chest radiograph showed a right-sided, apical, segmental consolidation, which improved with antimicrobial therapy. This radiograph shows opacity in the left upper zone, with tethering to the pleural space.

Chest radiograph in a 54-year-old man with asthma and an 8- to 9-month history of left-sided chest pain, anorexia, weight loss, and increasing shortness of breath (same patient as in the previous image). The patient had an episode of pneumonia 6 months earlier. A computed tomography (CT) scan obtained 3 weeks after the previous image shows enlargement of the left upper-zone opacity. An open lung biopsy was performed and showed microscopic changes characteristic of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

Chest radiograph in a 54-year-old man with asthma and an 8- to 9-month history of left-sided chest pain, anorexia, weight loss, and increasing shortness of breath (same patient as in the previous image). The patient had an episode of pneumonia 6 months earlier. A computed tomography (CT) scan obtained 3 weeks after the previous image shows enlargement of the left upper-zone opacity. An open lung biopsy was performed and showed microscopic changes characteristic of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

Chest radiograph in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows a left-sided unilateral focal/lobar consolidation associated with some loss of volume.

Chest radiograph in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows a left-sided unilateral focal/lobar consolidation associated with some loss of volume.

Pleural thickening occurs in 13% of patients, [22] and pleural effusions may be present. Migratory opacities or areas of consolidation may exist.

Ground-glass appearances are unusual on standard chest radiographs.

To assess the role of chest radiography in the differential diagnosis of BOOP and usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), Muller et al compared chest radiography, clinical information, and pulmonary function data, without knowledge of the pathologic diagnosis. [24] The clinical symptoms of BOOP were similar to those of UIP, although the duration of symptoms was longer in UIP, and the prevalence of systemic symptoms was higher in BOOP.

The physical findings in the study by Muller et al were similar, except that finger clubbing was more common in patients with UIP than in those with BOOP. No significant difference in lung volumes, flows, or diffusing capacity was recorded. In the majority of patients, UIP and BOOP could be distinguished on the basis of findings on chest radiographs. The most characteristic radiologic finding in BOOP was the presence of patchy areas of airspace consolidation. [24]

Diseases that may mimic BOOP include collagen disease, usual interstitial pneumonia, lung metastases, Wegener granulomatosis, eosinophilic pneumonia, primary bronchogenic neoplasm, and tuberculosis.

Computed Tomography

CT scan and high-resolution CT (HRCT) scan findings include the following [22, 25, 26, 27] :

-

Patchy ground-glass opacities in a subpleural and/or peribronchovascular distribution (80%)

-

Bilateral basal airspace consolidation (71%)

-

Bronchial wall thickening and cylindrical bronchial dilatation in areas of air bronchogram (71%) (See the image below.)

Standard nonenhanced axial thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows left lower-lobe consolidation with some loss of volume and an air bronchogram. Transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

Standard nonenhanced axial thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows left lower-lobe consolidation with some loss of volume and an air bronchogram. Transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

-

Centrilobular nodules 3-5 mm in diameter (50%)

-

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy (27%)

-

Small, nodular opacities measuring from 1 to 10 mm in diameter, typically ill defined (50%)

-

Cavitating lung mass (rare)

-

Pleural effusions (33%)

The early clinical and radiographic findings of interstitial pneumonitis (IP) are often similar to those of BOOP. [28, 29] Differentiation is important, because interstitial pneumonitis carries a poor prognosis. Analysis of certain HRCT findings has shown that traction bronchiectasis, interlobular septal thickening, and intralobular reticular are more prevalent in usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) than in BOOP. Lung parenchymal nodules and peripheral distribution are more prevalent in BOOP than in IP. Areas with ground-glass attenuation, airspace consolidation, and architectural distortion are common in IP and BOOP. Thus, when differentiating BOOP from interstitial pneumonitis, special consideration should be given to the aforementioned radiographic features. [30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36]

In the early stages, clinical and chest radiographic findings of acute AIP and BOOP may be similar; however, HRCT findings of acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) and BOOP may differ. Traction bronchiectasis, interlobular septal thickening, and intralobular septal thickening are significantly more prevalent in patients with AIP than in patients with BOOP, whereas parenchymal nodules and peripheral distribution are more prevalent in BOOP. Areas with ground-glass attenuation, airspace consolidation, and architectural distortion are common in AIP and BOOP.

Degree of confidence

Plain radiographic and CT findings are nonspecific in BOOP and may be seen in a variety of pulmonary infectious or inflammatory processes and neoplastic diseases. However, CT scanning is more sensitive than chest radiography in assessing disease pattern and distribution. CT scanning is also superior in determining the biopsy site; therefore, high-resolution CT (HRCT) is usually performed before lung biopsy.

The reverse halo sign (RHS) on chest CT is defined as a focal area of ground-glass attenuation with a surrounding ring of consolidation. The sign was initially thought to be specific for cryptogenic organizing pneumonia but was later found with a variety of infectious and noninfectious diseases. Marchiori et al published a review on the causes of the RHS. [37] The authors suggested that although the presence of RHS helps narrow the differential diagnosis, the final diagnosis is established on the basis of the clinical setting. Nevertheless, tissue diagnosis may be required to establish the diagnosis.

Organizing pneumonia is the most frequent cause of the RHS. However, other causes of RHS include granulomatous disease, infections in immunocompromised patients, invasive aspergillosis, pulmonary zygomycosis, noninvasive fungal infections (eg, paracoccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia), Wegener granulomatosis, radiofrequency ablation, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.

The RHS has been reported in the CT scans of 6 confirmed cases of COVID-19 pneumonia [38] .

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI has no true diagnostic role in BOOP, but it may have a role in the follow-up imaging of patients with the disease to assess treatment response or disease activity. In one study, by Gaeta et al, of the value of gadolinium-enhanced MRI in evaluating disease activity in chronic infiltrative lung diseases (sarcoidosis, BOOP, UIP, radiation pneumonitis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, rheumatoid lung, vasculitis, alveolar proteinosis, bronchoalveolar carcinoma, and/or CEP) in which T1-weighted breath-hold MRIs were obtained before and after administration of the contrast agent, 14 of 17 patients with active disease were found to have enhancing lesions. [39]

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma may mimic BOOP. The white lung sign is not commonly found in pulmonary consolidations that have been assessed with heavily T2-weighted sequences. However, although the sign is usually negative in patients with BOOP, one study found the sign to be positive in 5 out of 5 patients with bronchoalveolar carcinoma. [40]

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or magnetic resonance angiography scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness.

-

Standard nonenhanced axial thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows left lower-lobe consolidation with some loss of volume and an air bronchogram. Transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

-

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause. The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. She presented with migratory lung opacities and areas of consolidation. Radiograph shows areas of consolidation at the lung base, with an air bronchogram at the right lung base. A wedge-shaped, pleural-based opacity is demonstrated astride the lateral part of the lesser fissure.

-

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause (same patient as in the previous image). The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. Radiograph obtained 2 months after the previous image shows that the consolidation had moved to the right upper zone and both midzones.

-

Chest radiograph in an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause (same patient as in the previous 2 images). The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. Radiograph shows changing consolidation located in both midzones.

-

Photomicrograph of a transbronchial biopsy sample of the right upper-lobe bronchus of an 81-year-old woman with mitral- and aortic-valve stenosis, hiatal hernia, and iron-deficiency anemia of unknown cause. The patient had undergone right-sided mastectomy for a carcinoma of the breast 20 years earlier. The slide was a part of a series of sections that showed granulation tissue polyps within the lumina of the bronchioles and alveolar ducts. These were associated with patchy areas of organizing pneumonia consisting largely of mononuclear cells and foamy macrophages in the surrounding lung. Plugs of immature fibroblasts covered by cuboidal cells were seen. There was a variable degree of infiltration of interstitium and alveoli.

-

A 54-year-old man with asthma and an 8- to 9-month history of left-sided chest pain, anorexia, weight loss, and increasing shortness of breath. The patient had an episode of pneumonia 6 months previously, when a chest radiograph showed a right-sided, apical, segmental consolidation, which improved with antimicrobial therapy. This radiograph shows opacity in the left upper zone, with tethering to the pleural space.

-

Chest radiograph in a 54-year-old man with asthma and an 8- to 9-month history of left-sided chest pain, anorexia, weight loss, and increasing shortness of breath (same patient as in the previous image). The patient had an episode of pneumonia 6 months earlier. A computed tomography (CT) scan obtained 3 weeks after the previous image shows enlargement of the left upper-zone opacity. An open lung biopsy was performed and showed microscopic changes characteristic of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

-

Chest radiograph in a 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus shows a left-sided unilateral focal/lobar consolidation associated with some loss of volume.