Practice Essentials

Cervical spondylosis is a chronic degenerative condition of the cervical spine that affects the vertebral bodies and intervertebral disks of the neck (in the form of, for example, disk herniation and spur formation), as well as the contents of the spinal canal (nerve roots and/or spinal cord). Some authors also include the degenerative changes in the facet joints, longitudinal ligaments, and ligamentum flavum. [1]

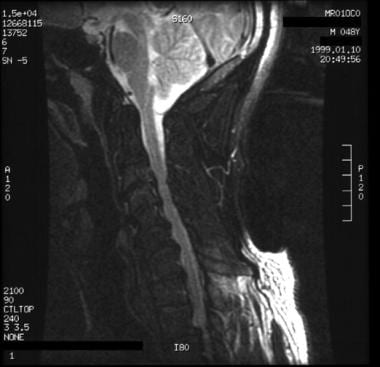

Spondylosis progresses with age and often develops at multiple interspaces. Chronic cervical degeneration is the most common cause of progressive spinal cord and nerve root compression. Spondylotic changes can result in stenosis of the spinal canal, lateral recess, and foramina. Spinal canal stenosis can lead to myelopathy, [2] whereas the latter 2 can cause radiculopathy. (See image below)

A T2-weighted cervical magnetic resonance imaging scan shows obliteration of the subarachnoid space as a result of spondylotic changes.

A T2-weighted cervical magnetic resonance imaging scan shows obliteration of the subarachnoid space as a result of spondylotic changes.

Signs and symptoms of cervical spondylosis

These include the following:

-

Cervical pain - Chronic suboccipital headache may be present

-

Cervical radiculopathy - Compression of the cervical nerve roots leads to ischemic changes that cause sensory dysfunction (eg, radicular pain) and/or motor dysfunction (eg, weakness)

-

Cervical myelopathy - Cervical spondylotic myelopathy is the most serious consequence of cervical intervertebral disk degeneration, especially when it is associated with a narrow cervical vertebral canal

Workup in cervical spondylosis

Plain cervical radiography is routine in every patient with suspected cervical spondylosis.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning, with or without intrathecal dye, can be used to estimate the diameter of the spinal canal. CT scans may demonstrate small, lateral osteophytes and calcific opacities in the middle of the vertebral body.

High–signal-intensity lesions can be seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of spinal cord compression; this finding indicates a poor prognosis. False-positive and false-negative MRI results occur frequently in patients with cervical radiculopathy; therefore, MRI results and clinical findings should be used when interpreting root compression. [3]

Management

Immobilization of the cervical spine is the mainstay of conservative treatment for patients with severe cervical spondylosis with evidence of myelopathy. Mechanical traction, a widely used technique, may be useful because it promotes immobilization of the cervical region and widens the foraminal openings. However, traction in the treatment of cervical pain was not better than placebo in two randomized groups.

The use of cervical exercises has been advocated in patients with cervical spondylosis. Isometric exercises are often beneficial to maintain the strength of the neck muscles. Neck and upper back stretching exercises, as well as light aerobic activities, also are recommended.

Indications for surgery include the following:

-

Progressive neurologic deficits

-

Documented compression of the cervical nerve root and/or spinal cord

-

Intractable pain

Pathophysiology

Intervertebral disks lose hydration and elasticity with age, and these losses lead to cracks and fissures. The surrounding ligaments also lose their elastic properties and develop traction spurs. The disk subsequently collapses as a result of biomechanical incompetence, causing the annulus to bulge outward. As the disk space narrows, the annulus bulges, and the facets override. This change, in turn, increases motion at that spinal segment and further hastens the damage to the disk. Annulus fissures and herniation may occur. Acute disk herniation may complicate chronic spondylotic changes.

As the annulus bulges, the cross-sectional area of the canal is narrowed. This effect may be accentuated by hypertrophy of the facet joints (posteriorly) and of the ligamentum flavum, which becomes thick with age. Neck extension causes the ligaments to fold inward, reducing the anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the spinal canal.

As disk degeneration occurs, the uncinate process overrides and hypertrophies, compromising the ventrolateral portion of the foramen. Likewise, facet hypertrophy decreases the dorsolateral aspect of the foramen. This change contributes to the radiculopathy that is associated with cervical spondylosis. Marginal osteophytes begin to develop. Additional stresses, such as trauma or long-term heavy use, may exacerbate this process. These osteophytes stabilize the vertebral bodies adjacent to the level of the degenerating disk and increase the weight-bearing surface of the vertebral endplates. (See images below) The result is decreased effective force on each of these structures.

A cervical myelogram shows advanced spondylotic changes and multiple compression of the spinal cord by osteophytes.

A cervical myelogram shows advanced spondylotic changes and multiple compression of the spinal cord by osteophytes.

A 59-year-old woman presented with a spastic gait and weakness in her upper extremities. A T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scan shows cord compression from cervical spondylosis, which caused central spondylotic myelopathy. Note the signal changes in the cord at C4-C5, the ventral osteophytosis, buckling of the ligamentum flavum at C3-C4, and the prominent loss of disk height between C2 and C5.

A 59-year-old woman presented with a spastic gait and weakness in her upper extremities. A T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scan shows cord compression from cervical spondylosis, which caused central spondylotic myelopathy. Note the signal changes in the cord at C4-C5, the ventral osteophytosis, buckling of the ligamentum flavum at C3-C4, and the prominent loss of disk height between C2 and C5.

A 48-year-old man presented with neck pain and predominantly left-sided radicular symptoms in the arm. The patient's symptoms resolved with conservative therapy. An axial, gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging scan shows moderate anteroposterior narrowing of the cord space due to a ventral osteophyte at the C4 level, with bilateral narrowing of the neural foramina (more prominently on the left side).

A 48-year-old man presented with neck pain and predominantly left-sided radicular symptoms in the arm. The patient's symptoms resolved with conservative therapy. An axial, gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging scan shows moderate anteroposterior narrowing of the cord space due to a ventral osteophyte at the C4 level, with bilateral narrowing of the neural foramina (more prominently on the left side).

A 48-year-old man presented with neck pain and predominantly left-sided radicular symptoms in the arm. The patient's symptoms resolved with conservative therapy. A T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scan shows ventral osteophytosis, most prominent between C4 and C7, with reduction of the ventral cerebrospinal fluid sleeve.

A 48-year-old man presented with neck pain and predominantly left-sided radicular symptoms in the arm. The patient's symptoms resolved with conservative therapy. A T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scan shows ventral osteophytosis, most prominent between C4 and C7, with reduction of the ventral cerebrospinal fluid sleeve.

Degeneration of the joint surfaces and ligaments decreases motion and can act as a limiting mechanism against further deterioration. Thickening and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) also decreases the diameter of the canal. [4, 5, 6]

The blood supply of the spinal cord is an important anatomic factor in the pathophysiology. Radicular arteries in the dural sleeves tolerate compression and repetitive minor trauma poorly. The spinal cord and canal size also are factors. A congenitally narrow canal does not necessarily predispose a person to myelopathy, but symptomatic disease rarely develops in individuals with a canal that is larger than 13 mm.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Cervical spondylosis is a common condition that is estimated to account for 2% of all hospital admissions. It is the most frequent cause of spinal cord dysfunction in patients older than 55 years. On the basis of radiologic findings, 90% of men older than 50 years and 90% of women older than 60 years have evidence of degenerative changes in the cervical spine.

International

Investigators in a study involving Ghanaians reported, "out of 225 patients who carried loads on their head, 143 (63.6%) had cervical spondylosis, and of the 80 people who did not carry load on their head, 29 (36%) had cervical spondylosis."

Mortality/Morbidity

The course of cervical spondylosis may be slow and prolonged, and patients may either remain asymptomatic or have mild cervical pain. Long periods of nonprogressive disability are typical, and in a few cases, the patient's condition progressively deteriorates.

Morbidity ranges from chronic neck pain, radicular pain, diminished cervical range of motion (ROM), headache, [7] myelopathy leading to weakness, and impaired fine motor coordination to quadriparesis and/or sphincteric dysfunction (eg, difficulty with bowel or bladder control) in advanced cases. The patient may eventually become chair bound or bedridden.

A retrospective cohort study by Lin et al suggested that cervical spondylosis increases the risk for migraine headaches. The investigators found the overall incidence of migraines in persons with cervical spondylosis to be 5.16 per 1000 people annually, compared with 2.09 per 1000 people annually in controls. The adjusted hazard ratio for migraine in cervical spondylosis was reported to be 2.03. In cervical spondylosis patients with myelopathy, the incidence of migraine was 2.19 times greater than in controls. [8]

A study by Woodworth et al suggested that cervical spondylosis leads to cortical thinning and atrophy in the brain, with resultant increases in neurologic symptoms and pain. Using high-resolution T1-weighted structure magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the investigators reported that in patients with cervical spondylosis, changes were seen in parts of the brain associated with sensorimotor function and pain processing, including cortical thinning in the superior frontal gyrus, anterior cingulate, and precuneus and volume reduction in the putamen. [9]

Race

No apparent correlation between race and cervical spondylosis exists.

Sex

Both sexes are affected equally. Cervical spondylosis usually starts earlier in men than in women.

Age

Symptoms of cervical spondylosis may appear in persons as young as 30 years but are found most commonly in individuals aged 40-60 years. Radiologic spondylotic changes increase with patient age; 70% of asymptomatic persons older than 70 years have some form of degenerative change in the cervical spine.

A retrospective study by Wang et al of 1276 cases of cervical spondylosis found an aging-related increase in the incidence of the condition—including bulge or herniation at C3-C4, C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7—in patients up to age 50 years and a decrease in the condition’s incidence with aging in patients older than 50 years, with the decrease particularly seen after age 60 years. Additionally, an aging-related increase in the incidence of hyperosteogenesis and spinal stenosis was found prior to age 60 years, with a decrease in incidence seen after age 60 years. [10]

Cervical spondylosis usually starts earlier in men than in women. When cervical spondylosis develops in a young individual, it is almost always secondary to a predisposing abnormality in one of the joints between the cervical vertebrae, probably as a result of previous mild trauma.

-

A cervical myelogram shows advanced spondylotic changes and multiple compression of the spinal cord by osteophytes.

-

A 59-year-old woman presented with a spastic gait and weakness in her upper extremities. A T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scan shows cord compression from cervical spondylosis, which caused central spondylotic myelopathy. Note the signal changes in the cord at C4-C5, the ventral osteophytosis, buckling of the ligamentum flavum at C3-C4, and the prominent loss of disk height between C2 and C5.

-

A T2-weighted cervical magnetic resonance imaging scan shows obliteration of the subarachnoid space as a result of spondylotic changes.

-

A 48-year-old man presented with neck pain and predominantly left-sided radicular symptoms in the arm. The patient's symptoms resolved with conservative therapy. An axial, gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging scan shows moderate anteroposterior narrowing of the cord space due to a ventral osteophyte at the C4 level, with bilateral narrowing of the neural foramina (more prominently on the left side).

-

A 48-year-old man presented with neck pain and predominantly left-sided radicular symptoms in the arm. The patient's symptoms resolved with conservative therapy. A T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scan shows ventral osteophytosis, most prominent between C4 and C7, with reduction of the ventral cerebrospinal fluid sleeve.