Practice Essentials

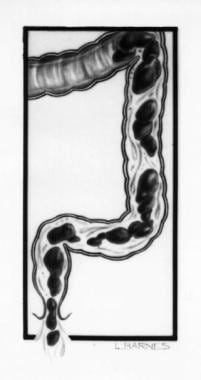

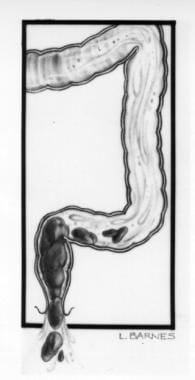

Encopresis is the involuntary discharge of feces (ie, fecal incontinence). In most cases, it is the consequence of chronic constipation and resulting overflow incontinence (see the images below), but a minority of patients have no apparent history of constipation or painful defecation. No good prospective data suggest that encopresis is primarily a behavioral or psychological disorder. The behavioral difficulties associated with encopresis are most likely the result of the condition rather than its cause.

Encopresis, along with enuresis, is classified as an elimination disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). It may be divided into two subtypes: encopresis with constipation (retentive encopresis) and encopresis without constipation.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of encopresis may include the following:

-

History of constipation (sometimes very remote) or painful defecation (~80-95% of children with encopresis)

-

Inability to differentiate passing gas and passing feces

-

Soiling episodes usually occurring during the daytime (soiling during sleep is uncommon)

-

With retentive encopresis, intermittent passage of extremely large bowel movements

Physical findings, other than those from abdominal and rectal examinations, are usually normal. Unless contraindicated, a digital rectal examination should be performed on every child with encopresis.

Examination may reveal the following:

-

Palpable stool throughout the distribution of the colon, especially in the left lower quadrant

-

Stool smeared around the anus

-

Lax and patulous anal sphincter

-

Rectum enlarged and filled with soft stool that yields negative results on fecal occult blood testing

Neurological findings should be normal. Patients should have a normal anal wink and normal sensation, strength, and reflexes in the lower extremities.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Other problems to be considered in the diagnosis include the following:

-

Spina bifida

-

Meningomyelocele

-

Spinal-cord injury with dysfunction of the anal sphincter

-

Tethered spinal cord

-

Ultrashort-segment Hirschsprung disease (ie, congenital megacolon)

-

Imperforate anus with fistula

In most patients, the diagnosis of encopresis is established on the basis of the history and complete physical examination, including a rectal examination. Laboratory studies are rarely warranted. The following studies may be helpful:

-

Plain abdominal radiography

-

Anorectal manometry

-

Biopsy (either surgical or done by means of a suction device)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Conventional medical therapy is commonly the first therapy attempted, generally consisting of the following:

-

Demystification and education

-

Colonic disimpaction followed by routine laxative therapy

-

“Toilet training”

Agents that can be used for disimpaction include the following:

-

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)

-

Sodium phosphate

-

Magnesium citrate

-

Enemas

Virtually any laxative can be used, provided that it is administered in sufficient quantity to produce 1-2 soft stools daily.

In addition to long-term laxative therapy, modalities that have been proposed for the treatment of chronic encopresis include the following:

-

Biofeedback therapy (efficacy not proved)

-

Intensive behavioral program (effective adjunct to conventional medical therapy)

Although the critical components of a successful intensive behavioral program have not been systematically elucidated, common elements of existing programs include the following:

-

Demystifying the condition and educating patients and families

-

Providing specific toileting instruction about appropriate positioning and straining

-

Designing a program of regular, timed, and uninterrupted toileting

-

Maintaining a symptom and toileting diary

-

Defining specific achievable target behaviors

-

Establishing age-appropriate rewards and consequences

-

Strongly emphasizing consistency

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Encopresis is the involuntary discharge of feces (ie, fecal incontinence). In most cases, it is the consequence of chronic constipation and resulting overflow incontinence, but a minority of patients have no apparent history of constipation or painful defecation. No good prospective data suggest that encopresis is primarily a behavioral or psychological disorder. The behavioral difficulties associated with encopresis are likely the result of the condition rather than its cause.

In most patients, the diagnosis of encopresis is established with the history and complete physical examination, including a rectal examination. Laboratory studies are rarely warranted, though radiography, manometry, and biopsy may be helpful. Treatment remains largely experiential and generally consists of demystification and education, colonic disimpaction followed by routine laxative therapy, and “toilet training.”

Diagnostic Criteria (DSM-5)

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), uses the term elimination disorder to classify both encopresis and enuresis. [1] Encopresis is further divided into two subtypes: encopresis with constipation (retentive encopresis) and encopresis without constipation. The latter subtype is much less common and most often occurs in association with oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder or as a consequence of anal masturbation.

DSM-5 criteria for encopresis are as follows [1] :

-

Repeated passage of feces into inappropriate places, whether involuntary or intentional

-

One such event occurs each month for at least 3 months

-

Occurs in children at least age 4 years (or of equivalent developmental level)

-

The behavior is not attributable to the physiologic effects of a substance or another medical condition except through a mechanism involving constipation

Pathophysiology

In the vast majority of cases, encopresis develops as a consequence of chronic constipation with resulting overflow incontinence (see the images below), [2] which is typically termed retentive encopresis; encopresis in the absence of a history of constipation or painful bowel movements is typically referred to as nonretentive. Many children with encopresis have a remote history of constipation or painful defecation [3] or demonstrate incomplete evacuation during defecation on physical examination or radiographic assessment. [4]

Chronic constipation due to irregular and incomplete evacuation results in progressive rectal distention and stretching of both the internal anal sphincter and the external anal sphincter (EAS). As the child habituates to chronic rectal distention, he or she no longer senses the normal urge to defecate. Soft or liquid stool eventually leaks around the retained fecal mass, resulting in fecal soiling.

Etiology

In most cases, encopresis is thought to develop as a consequence of chronic constipation with resulting overflow incontinence. Approximately 80-95% of children with encopresis have a history of constipation or painful bowel movements. The remaining 5-20% appear to have nonretentive encopresis and no history of constipation or painful defecation; they generally have no evidence of incomplete evacuation on physical evaluation or radiographic evaluation.

No good prospective data suggest that encopresis, whether retentive or nonretentive, is primarily a behavioral or psychological disorder. Rather, most of the available evidence indicates that children with encopresis do not have an increased incidence of major behavioral or personality disorders when compared with age-matched peers. [5] Overall, the evidence suggests that behavioral difficulties associated with encopresis may be the result of the encopresis rather than the cause. [6, 7]

No good evidence suggests that encopresis is an indicator of sexual abuse. [8] The incidence of fecal soiling is comparable among children with a history of sexual abuse and among children with psychiatric and behavioral disorders. [8, 9]

Children with encopresis are significantly more likely to have attention-deficit disorder/hyperactivity (ADHD) than the general population. [10, 11]

Low self-esteem or parent-child conflict as a result of the disorder is not uncommon. Embarrassed youngsters also frequently deny having the problem.

Epidemiology

Although few prospective studies have been conducted to examine the prevalence of encopresis in childhood, it is estimated that 1-2% of children younger than 10 years have encopresis. In a study of 482 children aged 4-17 years who were observed over a 6-month period in a primary care pediatric clinic in Iowa, 4.4% of the subjects experienced fecal incontinence at least once per week. [12]

Nearly all of the few published population-based studies examining the prevalence of encopresis have been conducted in North America and Europe. In one such study conducted in the Netherlands, 4.1% of children aged 5-6 years and 1.6% of children aged 11-12 years experienced fecal soiling at least once per month. [13] Studies conducted in Sweden and the United Kingdom [14] reported similar numbers.

In nearly all published series, boys are much more commonly affected than girls. In most series, approximately 80% of affected children are boys.

Prognosis

Even with aggressive medical and behavioral interventions, as many as 30% of children remain symptomatic. [15] Unfortunately, the available data are insufficient to enable clinicians to make reliable predictions as to which children will successfully respond to which specific treatment protocols.

Current evidence suggests that family disorganization correlates with a poor response to all forms of treatment. In contrast, no demographic, manometric, behavioral, social, academic, or self-esteem measures are clearly associated with response to therapy. No investigators have systematically examined the child’s motivation, the family’s motivation, or the state of change to determine whether any of these is predictive of the patient’s response to treatment.

Nonretentive encopresis may be associated with oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Urinary tract infection may be associated with encopresis, but is more frequently seen in females than in males.

-

Encopresis. Overflow incontinence.

-

Encopresis. Overflow incontinence.