Practice Essentials

Bicuspid aortic valve is a common congenital anomaly but does not cause functional problems unless aortic valve stenosis, aortic valve regurgitation, aortic root dilatation, or dissection or infective endocarditis occurs. Follow up for development of these functional lesions is indicated. Routine endocarditis prophylaxis is not recommended, but maintaining good oral and dental hygiene is emphasized. Routine endocarditis prophylaxis is indicated if there is prior history of endocarditis, prosthetic valve placement or for 6-months after complete repair of heart defect.

Background

Sir William Osler was one of the first to recognize the bicuspid aortic valve as a common congenital anomaly of the heart. [1] Leonardo da Vinci recognized the superior engineering advantages of the normal trileaflet valve. [2] However, bicuspid aortic valve is mentioned only briefly in many pediatric and cardiology textbooks.

Definition

The normal aortic valve has three equal-sized leaflets or cusps with three lines of coaptation. A congenitally bicuspid aortic valve has two functional leaflets. Most have one complete line of coaptation. Approximately half of cases have a low raphe. Stenotic or partially fused valves caused by inflammatory processes, such as rheumatic fever, are not included in this chapter.

Embryology

The embryonic truncus arteriosus is divided by the spiral conotruncal septum during development. The normal right and left aortic leaflets form at the junction of the ventricular and arterial ends of the conotruncal channel. The nonseptal leaflet (posterior) cusp normally forms from additional conotruncal channel tissue. Abnormalities in this area lead to the development of a bicuspid valve, often through incomplete separation (or fusion) of valve tissue. [3]

Bicuspid aortic valve is often observed with other left-sided obstructive lesions such as coarctation of the aorta or interrupted aortic arch, suggesting a common developmental mechanism. [4] Specific gene mutations have been isolated. [5, 6]

Anatomy

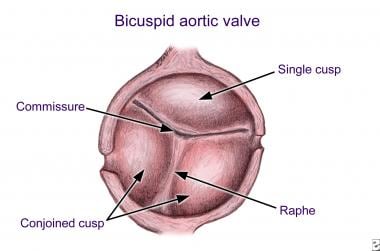

The bicuspid valve is composed of two leaflets or cusps, usually of unequal size. [7, 8] See the image below.

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Bicuspid aortic valve with unequal cusp size. Note eccentric commissure and raphe.

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Bicuspid aortic valve with unequal cusp size. Note eccentric commissure and raphe.

The larger leaflet is referred to as the conjoined leaflet. Two commissures (or hinge points) are present; usually, neither is partially fused. The presence of a partially fused commissure, also called a high raphe, probably predisposes toward eventual stenosis. At least half of all congenitally bicuspid valves have a low raphe, which never attains the plane of the attachments of the two commissures and never extends to the free margin of the conjoined cusp. Redundancy of a conjoined leaflet may lead to prolapse and insufficiency. [9]

Valve leaflet orientation and morphology can vary. A recent surgical study showed conjoined leaflets in 76% of specimens. [10] Of these, fusion of the raphe was noted between the right and left cusps in 86%, and fusion was noted between the left and noncoronary cusps in only 3%. Of the valves without raphes, more than 30% of the leaflets were unequal in size.

Coronary arteries may be abnormal. [8] A left-dominant coronary system (ie, posterior-descending coronary artery arising from the left coronary artery) is more commonly observed with bicuspid aortic valve. Rarely, the left coronary artery may arise anomalously from the pulmonary artery. The left main coronary artery may be up to 50% shorter in patients with a bicuspid aortic valve. Occasionally, the coronary ostium may be congenitally stenotic in association with bicuspid aortic valve.

The aortic root may be dilated. [11] This dilatation has some similarities to the dilatation of the aorta seen in Marfan syndrome. [12, 13] The dilatation may involve the ascending aorta (most commonly) but may also involve the aortic root or transverse aortic arch. [14, 15, 16, 17] A recent study compared aortic dilation in children who had bicuspid aortic valve with and without coarctation of the aorta; the conclusion was that valve morphologic characteristics and function and age at the time of coarctation of the aorta repair had no impact to minimal impact on aortic dimensions. [18]

Pathophysiology

With degeneration of aging valves, sclerosis and calcification can occur. [19] The changes are similar to those in atherosclerotic coronary arteries. The bicuspid valve may also be completely competent, producing no regurgitant flow. However, redundancy and prolapse of cusp tissue can lead to valve regurgitation. Complications arise in as many as one third of patients over their lifetimes [20] ; this disorder, therefore, deserves close attention and medical follow-up.

Valve morphology may be predictive of problems of stenosis, insufficiency, or both. Fusion along the right or left leaflets is less commonly associated with stenosis or insufficiency in children. This arrangement is much more common in patients with coarctation of the aorta, whose valves function adequately. Fusion along the right and noncoronary leaflets is more frequently associated with pathologic changes of stenosis or insufficiency in the pediatric population. [21]

Epidemiology

United States data

Bicuspid aortic valves may be present in as many as 1-2% of the population. Because the bicuspid valve may be entirely silent during infancy, childhood, and adolescence, these incidence figures may be underestimated and are not generally included in the overall incidence of congenital heart disease.

International data

Incidence does not appear to be affected by geography.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

A recent report suggests much lower than expected prevalence in African-Americans. [22]

The male-to-female ratio is 2:1 or greater. Sex is not a predictive variable in the natural history of bicuspid aortic valve. A recent prospective echocardiographic study in newborn infants showed a prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve in 7.1 per 1,000 male newborns versus 1.9 per 1,000 female newborns. [23]

Bicuspid aortic valve may be identified in patients of any age, from birth through the 11th decade of life. It may be only an incidental finding at autopsy. Bicuspid aortic valve may remain silent and be discovered as an incidental finding on echocardiographic examination of the heart.

Critical aortic stenosis and infective endocarditis may be considered relatively early sources of morbidity for patients with bicuspid aortic valve. Critical aortic stenosis may occur in infancy and may be associated with a bicuspid valve.

Occasionally, bicuspid aortic valve is diagnosed after a patient has developed infective endocarditis with systemic embolization.

Stenosis of a bicuspid aortic valve is more likely to develop in persons older than 20 years and is caused by progressive sclerosis and calcification. High levels of serum cholesterol have been associated with more rapidly progressive sclerosis of the congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. [24]

Children who develop early progressive, pathologic changes in the bicuspid aortic valve are more likely to develop valve regurgitation than stenosis. Bicuspid aortic valve was identified in 167 (0.8%) of 20,946 young Italian military conscripts. Of these, 110 were found to have either mild or moderate aortic insufficiency.

Prognosis

Overall prognosis for the individual with bicuspid aortic valve is good. Reviews and reports in the past have emphasized the fairly benign course for patients with bicuspid valves. However, more recent reports on the natural history of these valves suggest numerous more serious problems and an acceleration of normal valvular wear and tear. These problems may not develop until adulthood. Routine and regular follow-up for the child or adolescent with bicuspid aortic valve is recommended.

Complications

Overall complication rates in patients with bicuspid aortic valves vary. [20] In general, bicuspid aortic valve may be a common reason for acceleration of the normal aging process (eg, valve sclerosis, calcification). Four specific complications are related to the congenitally bicuspid aortic valve: aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency, infective endocarditis, and aortic root dissection.

Aortic stenosis

Sclerosis of the bicuspid aortic valve generally begins in the second decade of life, and calcification becomes more concerning during and after the fourth decade of life. [25] The presence of coronary risk factors (eg, smoking, hypercholesterolemia) may accelerate these processes.

Approximately 50% of adults with severe aortic stenosis have a congenitally bicuspid valve.

Historically, rheumatic fever was the most common cause of aortic stenosis. With significantly decreasing incidence of rheumatic fever in developed nations, bicuspid aortic valve is the most common cause of aortic stenosis in adults and is probably the most common etiology of valve insufficiency as well. Acute rheumatic fever and its recurrences are still a major problem in developing countries, and, in these areas, long-term effects of rheumatic fever are still more significant than bicuspid valve in the etiology of aortic stenosis and insufficiency. Rheumatic aortic valve damage can be confirmed only at surgery or autopsy by the presence of Aschoff bodies by histology.

Aortic insufficiency

Most cases of severe aortic insufficiency are related, either directly or indirectly, to a congenitally bicuspid valve.

Numerous factors may contribute to development of aortic valve insufficiency. These include cusp prolapse, erosion of irregular commissure lines, aortic root dilatation (particularly at the sinotubular junction or supra-aortic ridge), infective endocarditis, and systemic hypertension (particularly with coarctation).

Infective endocarditis

The risk of developing infective endocarditis on a bicuspid aortic valve is 10-30% over a lifetime.

Bicuspid aortic valve is the second most common congenital etiology for infective endocarditis in infants and children; [26] overall, approximately 25% of endocarditis infections develop on a bicuspid valve.

Aortic root dissection

Enlargement of the root is often attributed to poststenotic dilatation. However, the root may dilate without significant valve stenosis, and abnormal histology with broken elastic fibers and other findings suggestive of Marfan syndrome has been identified in numerous studies. [12, 13] Findings on histologic studies of the aortic root in individuals with bicuspid aortic valve are controversial. [27]

The risk of aortic root dissection is much higher for individuals with Marfan syndrome (approximately 40%) than for those with bicuspid aortic valve (approximately 5%). However, because bicuspid aortic valve is more prevalent in the general population, this disorder is more commonly associated with aortic root dissection.

A population-based, retrospective cohort study assessed the complications of patients with bicuspid aortic valve living in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Of the 416 patients studied over a mean follow-up of 16 years, reported incidence of aortic dissection was low (2 of 416), but it was significantly higher than in the general population. [28]

Patient Education

Patient and family education should emphasize the fairly benign course for the child with bicuspid aortic valve.

Older children and adolescents should begin to be made aware of the accelerated aging processes (ie, progressive stenosis), with particular attention to coronary risk factors. Therefore, patients should be encouraged to maintain healthy diet, exercise regularly, and avoid coronary risk factors such as smoking.

The importance of bicuspid aortic valve as a potential substrate for infective endocarditis should be emphasized. Even though routine endocarditis prophylaxis is not recommended by the American Heart Association, good oral and dental hygiene is important—along with regular dental care by professionals at least once every 6 months.

Most young individuals with bicuspid aortic valve should not require restrictions in physical activity or sports participation, unless they have significant stenosis or regurgitation. Routine examination is recommended prior to sports participation at least once.

-

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Bicuspid aortic valve with unequal cusp size. Note eccentric commissure and raphe.

-

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Parasternal long-axis echocardiogram showing doming of a bicuspid aortic valve.

-

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view in diastole, showing bicuspid aortic valve with nearly equal cusp size and right-left orientation of the commissure. Note the two color signals showing minimal aortic insufficiency.

-

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Two-dimensional echocardiogram of typical bicuspid aortic valve in diastole and systole. Valve margins are thin and pliable and open widely, creating the fishmouth appearance.

-

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Long-axis and short-axis transthoracic echocardiograms showing a bicuspid aortic valve. In diastole, hammocking (prolapse) of the valve cusps occurs. The short-axis view shows the irregular sclerotic margins. This type of bicuspid valve is the most commonly replaced, typically because of insufficiency.

-

Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Basilar oblique transesophageal image showing congenitally bicuspid aortic valve with vegetation (due to Streptococcus viridans endocarditis).