Background

Fuchs endothelial dystrophy (FED) is characterized by an asymmetrical, bilateral, slowly progressive edema of the cornea in elderly patients. When inherited, the transmission is autosomal dominant. Corneal endothelium is a monolayer of cells that acts as the major pump to deturgesce the cornea and ensures clarity. The normal attrition rate of endothelial cells is 0.6% per year; the rate is accelerated in Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. The root cause of the condition is a slowly progressive formation of guttate lesions between the corneal endothelium and the Descemet membrane. [1] These wartlike, anvil-shaped or mushroom-shaped excrescences are said to be abnormal elaborations of basement membrane and fibrillar collagen by distressed or dystrophic endothelial cells. As the lesions enlarge, the covering endothelial cells initially become stretched, and they eventually fall off. [1] Examples are shown in the images below.

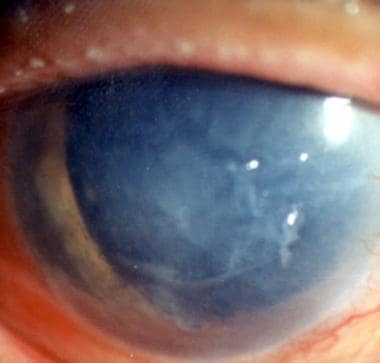

Familial Fuchs endothelial dystrophy in a 65-year-old female. The other eye presented similarly. Her father and older brother were reported to have the same malady.

Familial Fuchs endothelial dystrophy in a 65-year-old female. The other eye presented similarly. Her father and older brother were reported to have the same malady.

The left eye of a 75-year-old man showing fully developed Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. The optical section shows marked thickening of the central part of the cornea and lifting up of the epithelium. Bullae formation is seen on the nasal side. The epithelium is thickened.

The left eye of a 75-year-old man showing fully developed Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. The optical section shows marked thickening of the central part of the cornea and lifting up of the epithelium. Bullae formation is seen on the nasal side. The epithelium is thickened.

Growth of cornea guttata progresses from the center of the cornea to the periphery. As the endothelial cells fall, the remaining cells enlarge to cover the gap. With the reduced number of endothelial cells, the pump function suffers. Endothelial cell attrition rises with increasing number and size of the guttate lesions. Cornea guttata may be discovered accidentally or when specular endothelial microscopy is performed to find out the cause of the visual disturbance. [2] Studies have indicated the possibility of associated anterior stromal changes in the form of keratocyte depletion in this condition. [3]

Fuchs endothelial dystrophy passes through 4 clinical stages. These stages evolve over a period of 2 or 3 decades. The changes are bilateral but usually asymmetric.

Stage 1

This stage is cornea guttata. It occurs in the fourth or fifth decade of life. Slit lamp examination by specular reflection may show cornea guttata in the central part of the corneal endothelium. Examples are shown in the images below.

Severe cornea guttata in a 61-year-old woman. The endothelium is speckled with pigment. This patient had complained of mistiness in her otherwise excellent vision.

Severe cornea guttata in a 61-year-old woman. The endothelium is speckled with pigment. This patient had complained of mistiness in her otherwise excellent vision.

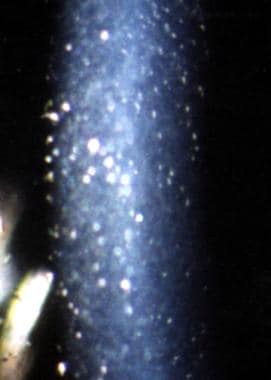

Specular endothelial microscopy in a case of severe cornea guttata with transparent cornea. The guttata lesions have affected many individual cells and groups of cells.

Specular endothelial microscopy in a case of severe cornea guttata with transparent cornea. The guttata lesions have affected many individual cells and groups of cells.

Some pigment dusting also may be seen. The excrescences of corneal guttata increase in number and may become confluent, resulting in a beaten metal appearance of the endothelial surface. The condition spreads from the center toward the periphery.

The patient usually has no complaints at this stage. Some very observant patients notice that the quality of their 20/20 vision is not the same as before. A slit lamp examination of the endothelium leads to the diagnosis.

Stage 2

This stage is characterized by increasing visual and other problems, caused by incipient edema of the corneal stroma initially and later the epithelium. The patient sees halos around lights and also experiences blurred vision and glare. Tiny droplets of corneal epithelial edema (bedewing) are best seen using retroillumination. The epithelial microcysts later coalesce and form bullae; hence, the name bullous keratopathy. The bullae rupture and expose the cornea to the danger of infectious keratitis. The patient experiences foreign body sensation and pain. Corneal sensitivity is reduced by the destruction of the epithelial nerve endings.

Slit lamp examination shows typical changes quite early. The posterior corneal lamellae are first to become edematous. They cause wrinkling in the Descemet membrane, termed striae. Epithelial edema is seen later.

Stage 3

In this stage, subepithelial connective tissue and pannus formation along the epithelial basement membrane are present. The periphery of the cornea becomes vascularized. A reduction of bullae formation occurs. The epithelial edema is reduced, so that the patient is more comfortable. However, the stromal edema remains. The epithelial layer is strengthened by the underlying pannus and fibrous tissue.

No medical treatment is known to prevent or stop the formation of cornea guttata. Hyperosmotic drops and ointment and bandage contact lenses may help for a time. Once the vision becomes adversely affected, a penetrating graft is advised at the convenience and the need of the patient. A deep lamellar endothelial graft is new, potentially effective alternate technique. The results of surgery in Fuchs endothelial dystrophy are excellent in most cases.

Stage 4

The chronicity of the disease leads to fibrovascular proliferation, followed by end-stage subepithelial scarring. This decreases the vision further.

No known medical treatment prevents or stops the formation of cornea guttata. Hyperosmotic drops and ointment and bandage contact lenses may help temporarily. Once the vision becomes adversely affected, an endothelial graft is advised. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) is the latest surgical technique for Fuchs endothelial dystrophy, and the results of this surgery are excellent in most cases.

Pathophysiology

The cornea is a highly specialized tissue with unique physiological functions of the various constituents that help to keep it transparent. The endothelium plays a major role in maintaining corneal transparency. Oxygen from the anterior chamber serves the needs of the endothelium and the posterior layers of the cornea. The essential nutrients (eg, glucose, amino acids) pass through it to provide for the cellular elements of all the layers of the cornea. The endothelial monolayer is responsible for relative deturgescence. This is completed in 2 ways: (1) by acting as a barrier to the movement of salt and metabolites into the stroma, and (2) by actively pumping bicarbonate ions out of the stroma and back to the aqueous humor.

In Fuchs dystrophy, the basic lesion appears to be cornea guttata. [1] Upon ultrastructural examination, this newly deposited abnormal portion of Descemet membrane consists of bundles and sheets of widely spaced, banded collagen and multiple laminations of basement membrane material. Endothelial cells may produce these wartlike, mushroom-shaped or anvil-shaped excrescences. Guttate excrescences in the peripheral cornea are of no consequence. However, their strong presence in the center of the cornea foreshadows trouble in the coming years. The increasing cornea guttata thins and progressively destroys the endothelial cells. The remaining cells enlarge and cover the gaps.

A stage comes, when because of the reduced number of functioning endothelial cells, the barrier and pump functions fail to maintain the delicate balance, and excessive hydration of the cornea starts (decompensation). The edema fluid separates the corneal lamellae and forms "fluid lakes." The separation of collagen fibrils leads to clouding of the cornea. As the disease progresses, the edema fluid enters the epithelium, resulting in an irregular epithelial surface. The retinal image becomes increasingly blurred. The edema varies from slight bedewing to frank bullae formation. Mild-to-moderate cornea guttata can remain as such for years without affecting vision. Only when stromal, and especially epithelial, edema manifest is the condition called Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. As the disease advances, vascular connective tissue is formed under and in the epithelium. This condition is followed by secondary complications (eg, epithelial erosions, microbial ulceration, corneal vascularization).

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Exact incidence of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy is not known. It begins with the formation of guttate excrescences. Cornea guttata is seen quite often. Frequency of cornea guttata increases with age. After age 40 years, 70% of patients have cornea guttata. Only 0.1% of these patients have epithelial edema and bullae formation.

International

A cross-sectional study in Japan found the prevalence of cornea guttata to be 4.1% among residents aged 40 years or older using only specular microscopic criteria. [4] Older age, female sex, and a thinner cornea were independently associated with a higher risk of cornea guttata.

Mortality/Morbidity

Once corneal decompensation starts, the course is relentless. In a matter of months or years, the vision is progressively disturbed. Finally, the patient is visually crippled. In addition, problems caused by repeated bullae formation, ulceration, scarring, and vascularization occur. If left untreated, the condition ends in near blindness, which may be painful.

Race

No race is immune from this condition.

Sex

Females are affected more than males (3:1).

Age

Fuchs endothelial dystrophy can be differentiated into early-onset (manifesting in the third decade of life) and late-onset (manifesting in the sixth decade of life, on average). However, the root of the condition is evident 1 or 2 decades earlier in the form of profuse cornea guttata in the central part of the cornea.

Prognosis

As a result of a successful corneal graft, patients experience complete freedom from bullae formation, pain, and irritation.

A high percentage of patients will have excellent transparency of the graft.

If the host cornea is not vascularized, the chances of graft rejection are minimized.

If the crystalline lens is transparent and the macular function is good, the chance of the patient regaining excellent vision is great.

Secondary procedures may be necessary to minimize astigmatism and any gross refractive error.

If the cornea has been vascularized as a result of repeated erosions and ulcer formation, the long-term results are less predictable.

Patient Education

As long as the vision is good for practical purposes, with or without local medication, surgery is not needed.

If a patient develops a cataract, that patient will need cataract surgery with or without keratoplasty. The surgeon in consultation with the patient will make the final decision.

This corneal condition needs a long-term, close interaction between the patient and the ophthalmologist.

The less affected eye needs as much attention as the affected eye.

Since the condition can be familial, other members of the family should have an eye examination.

A regular balanced diet and exercise are as useful to the body as they are to the eye.

Genetics and Inheritance

Proteomic and gene expression analyses may aid in clarifying the underlying mechanism and etiology of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. Several gene expression profiles have been investigated and were found to differ in Fuchs endothelial dystrophy corneas as compared to normal corneas. Based on these analyses, there is increasing evidence that interaction between genetic and environmental factors contribute to the complex alterations in the proteome and genome of the diseased endothelial cells and that addressing such interactions will enable better characterization of the pathogenic mechanisms involved. [5] In addition to decreased antioxidant defense, distinct oxidative DNA damage has been identified, indicating that mitochondria are the primary targets of oxidative damage in Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. One of the first genetic defects identified in Fuchs endothelial dystrophy was mutations in the COL8A2 gene, which are associated with early-onset Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. [6]

A new IC3D classification system for corneal dystrophies consists of four categories that reflect the known genetic and pathologic evidence for a given dystrophy. [7] Fuchs endothelial dystrophy falls into categories 1-3; category 4 is reserved for suspected new corneal dystrophies and does not fit the profile of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. Some of the inherited cases of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy are autosomal dominant. [8]

Category 1 indicates a well-defined corneal dystrophy in which the gene has been identified and a specific mutation is known. [7] Early-onset Fuchs endothelial dystrophy, mapped to COL8A2 (FECD C1), fits into this category. Early-onset Fuchs endothelial dystrophy usually begins in the first decade of life and becomes clinically detectable in the second and third decades.

Category 2 indicates a well-defined corneal dystrophy that has been mapped to one or more specific chromosomal loci, but the gene or genes have not been identified. [7] Familial Fuchs endothelial dystrophy is included in this category (FECD C2), in which multiple chromosomal loci have been mapped. Familial Fuchs endothelial dystrophy is described in the literature as a primarily autosomal dominant condition. [8, 9]

Category 3 indicates a well-defined corneal dystrophy in which the chromosomal locus has not been identified and accounts for a large percentage of familial Fuchs endothelial dystrophy cases. [7] The IC3D classification applies only to hereditary cases of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy and does not apply if no evidence of inheritance has been established. Moreover, some authors argue that most Fuchs endothelial dystrophy cases are more like a degeneration than a dystrophy because of late onset, lack of family history of the disease, and occasional asymmetric pattern, commonly associated with degeneration. [10]

Results of a genomewide association study and replication studies showed that E2-2 protein was associated with Fuchs corneal dystrophy (FCD). The association of alleles in the transcription factor 4 gene (TCF4), which encodes an E2-2 protein, increased the odds of FCD by 30 for homozygotes. This type of genetic testing may be useful in the future. [11]

It was also shown that approximately 5% of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy cases in Chinese patients and 4% of cases in Indian patients can be attributed to mutations in the SLC4A11 gene. [12]

The first genetic locus for late-onset Fuchs endothelial dystrophy (called FCD1) that was mapped to the 13pTel-13q12.13 interval followed a typical autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. [13] A second locus for late-onset Fuchs endothelial dystrophy (FCD2) was mapped to 18q21.2-q21.32. [14] More recently, the FCD3 locus was identified in a single large family at the 5q33.1-q35.2 interval. [15]

-

Familial Fuchs endothelial dystrophy in a 65-year-old female. The other eye presented similarly. Her father and older brother were reported to have the same malady.

-

The left eye of a 75-year-old man showing fully developed Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. The optical section shows marked thickening of the central part of the cornea and lifting up of the epithelium. Bullae formation is seen on the nasal side. The epithelium is thickened.

-

Close-up view of the limbal area of the same patient as in Media file 2. It clearly shows thickening of the epithelium, bullae formation, and vascularization of the cornea.

-

An optical section through the right cornea of the same patient as in Media file 3. It shows edema of the cornea and severe endothelial changes. The endothelial cell count in this eye was 800 cells/mm2.

-

Severe cornea guttata in a 61-year-old woman. The endothelium is speckled with pigment. This patient had complained of mistiness in her otherwise excellent vision.

-

Slit lamp examination under high magnification of a 54-year-old man, showing severe cornea guttata. The cornea illuminated by retroillumination from the edge of the slit light on the iris resembles dewdrops.

-

Pseudoguttata produced by uveal inflammation. Corneal edema is also present. The other eye was normal. These "guttata" disappeared completely under treatment.

-

Specular endothelial microscopy in a case of severe cornea guttata with transparent cornea. The guttata lesions have affected many individual cells and groups of cells.

-

Corneal edema in the eye of a 67-year-old woman.

-

Slit-lamp photograph of a 58-year-old man with epithelial bedewing and stromal and endothelial edema due to Fuchs endothelial dystrophy.

-

Ocular coherence tomography (OCT) image of a patient with Fuchs endothelial dystrophy showing gross corneal edema of 850 microns and epithelial bullae formation.

-

Ocular coherence tomography (OCT) image of the same patient as above with Fuchs endothelial dystrophy after undergoing Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) and showing overall compact cornea with a thickness of 450 microns and thin attached DMEK graft.

-

Slit lamp photograph of a 62-year-old man with Fuchs endothelial dystrophy showing corneal stromal edema and Descemet folds.

-

Slit lamp photograph of the same patient as above who underwent DMEK and showed symptomatic amelioration. Her vision improved to 20/40.

-

Slit lamp photograph on postoperative day 1 of a patient who underwent Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), showing an intact and well-adherent graft, compact cornea inferior peripheral iridectomy, and an air bubble.

-

Ocular coherence tomography picture of a patient with Fuchs endothelial dystrophy showing gross corneal edema of 850 microns and epithelial bullae formation.