Practice Essentials

Granulosa-theca cell tumors, also known as granulosa cell tumors (GCTs), represent about 2% of all ovarian tumors. GCTs can be divided into adult (95%) and juvenile (5%) types based on histologic findings. See the image below.

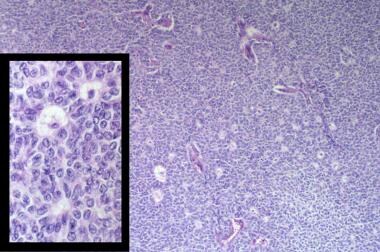

Microfollicular pattern of an adult granulosa cell tumor at 100X magnification. Inset is characteristic Call-Exner bodies and nuclear grooves (400X). Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.

Microfollicular pattern of an adult granulosa cell tumor at 100X magnification. Inset is characteristic Call-Exner bodies and nuclear grooves (400X). Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.

Signs and symptoms

Many patients with GCTs exhibit manifestations of hyperestrogenism. These symptoms vary depending on the patient’s age and menstrual status. In most patients, a palpable mass can be detected during the physical examination.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies

A pregnancy test is recommended for all reproductive-aged patients (even at the extremes of reproductive age) who present with abdominopelvic symptoms.

The standard laboratory workup for a patient with an adnexal mass varies depending on patient age, as follows:

-

In patients who are prepubertal or younger than 30 years, especially if the mass has solid components: Beta–human chorionic gonadotropin (bhCG), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and cancer antigen 125 (CA125)

-

In reproductive-aged women older than 30 years: CA125 test, serum inhibin levels, and serum sex hormone levels if clinical findings are consistent with excess hormone production

-

In postmenopausal women: CA125 test and serum sex hormone levels if findings are consistent with excess hormone production

Ancillary laboratory studies that may be useful include stool guaiac testing, complete blood cell (CBC) count with differential, blood chemistries, urinalysis, and cervical cultures for gonorrhea and chlamydia.

Imaging studies

Imaging studies that may be useful in the workup include the following:

-

Transvaginal sonography

-

Chest radiography

-

Abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

Mammography: For women aged older than 40 years who have not had a mammogram in the preceding 6-12 months

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Surgery is considered first-line therapy for patients with GCTs. Chemotherapy can be used as adjuvant therapy in patients with advanced or recurrent disease and has been effective in improving disease-free survival. A number of different chemotherapy regimens have been used in this setting, with varying toxicity and response rates.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Three major types of ovarian neoplasms are described, with epithelial cell tumors (>70%) comprising the largest group of tumors. Germ cell tumors occur less frequently (20%), while sex cord–stromal tumors make up the smallest proportion, accounting for approximately 8% of all ovarian neoplasms.

Granulosa-theca cell tumors, more commonly known as granulosa cell tumors (GCTs), belong to the sex cord–stromal category and include tumors composed of granulosa cells, theca cells, and fibroblasts in varying degrees and combinations. GCTs account for approximately 2% of all ovarian tumors and can be divided into adult (95%) and juvenile (5%) types based on histologic findings.

Both subtypes commonly produce estrogen, and estrogen production often is the reason for early diagnosis. However, while adult GCTs (AGCTs) usually occur in postmenopausal women and have late recurrences, most juvenile GCTs (JGCTs) develop in individuals younger than 30 years and often recur within the first 3 years. Theca cell tumors almost always are benign and carry an excellent prognosis. The rare malignant thecoma likely represents a tumor with a small admixture of granulosa cells. For this reason, the remainder of the article focuses on GCTs, except where indicated.

Recognition of the signs and symptoms of abnormal hormone production and consideration of these tumors in the differential diagnosis of an adnexal mass can allow for early identification, timely surgical management, and excellent cure rates. Despite the good overall prognosis, long-term follow-up always is required in patients with GCTs. [1]

No means of preventing sex cord–stromal tumors of the ovary are known.

Pathophysiology

Two theories exist to explain the etiology of sex cord–stromal tumors. The first proposes that these neoplasms are derived from the mesenchyme of the developing genital ridge. The second purports that sex cord and stromal cells of the mature ovary are derived from precursors found within the mesonephric and coelomic epithelium.

Reports of extraovarian GCTs can be found in the literature and may lend support to the derivation of this class of tumors from epithelium of the coelom and mesonephric duct.

Various theories propose explanations for the differentiation of normal granulosa and/or stromal cells into neoplastic entities. To date, no clear etiologic process has been identified. However, the most recent molecular data regarding these tumors have linked a missense point mutation (C402G) in the FOXL2 gene to granulosa cell tumors. [2] Using whole transcriptome sequencing of 4 adult GCTs, the mutation in FOXL2 was identified. They confirmed this mutation was present in an additional 86 of 89 adult GCTs, 3 of 14 thecomas, and 1 in 10 juvenile-type GCTs. Moreover, the mutation was not found in any of 49 sex cord stromal tumors of other types or in epithelial ovarian tumors. This suggests a potential pathogenic mutation and raises the possibility of identifying novel targeted therapies. [3]

GCTs are thought to be tumors of low malignant potential. Most of these tumors follow a benign course, with only a small percentage showing aggressive behavior, perhaps due to early stage at diagnosis. Metastatic disease can involve any organ system, although tumor growth usually is confined to the abdomen and pelvis.

Etiology

No definite etiologies for GCTs have been found. Proposed etiologies include chromosomal anomalies and/or autocrine and endocrine signaling abnormalities. A multifactorial etiology has been postulated.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The American Cancer Society estimates that 21,410 new cases of ovarian cancer will be diagnosed in 2021 and 13,770 women will die from the disease. [4] Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecologic malignancies. Because sex cord–stromal tumors account for only 5% of all ovarian tumors and approximately 8% of all malignant ovarian neoplasms, each year only 1500-2000 new cases of these tumors are diagnosed in the United States.

International statistics

Unlike epithelial ovarian cancers, no racial or ethnic predilection is found for ovarian germ cell or sex cord–stromal tumors. The incidence of this group of tumors essentially is the same throughout the world, as witnessed by similar frequency of these tumors in Japan, Sweden, and the West Indies.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Limited available data show that this class of neoplasms makes up a similar proportion of ovarian malignancies in the United States, Europe, the Far East, and the West Indies.

Granulosa cell tumors can occur in the juvenile and adult male testes, albeit very rarely. The frequency of GCTs in the male testes is even lower than that of GCTs in females and is the least common sex cord stromal tumor in the testes.

AGCTs account for 95% of all GCTs and usually are seen in postmenopausal women, with a median age at diagnosis of 52 years.

JGCTs comprise only 5% of all GCTs, and almost all of these tumors are found in patients younger than 30 years.

Theca cell tumors (ie, thecomas) account for less than 1% of all ovarian tumors, and the mean age at diagnosis is 53 years. These tumors are rare in women younger than 30 years, with the exception of the luteinized thecoma, which tends to occur in younger women.

Prognosis

The prognosis for granulosa-theca cell tumors generally is very favorable. GCTs are considered to be tumors of low malignant potential. Approximately 90% of GCTs are at stage I at the time of diagnosis (see Staging for further detail). The 10-year survival rate for stage I tumors in adults is 90-96%. GCTs of more advanced stages are associated with 5- and 10-year survival rates of 33-44%. The overall 5-year survival rates for patients with AGCTs or JGCTs are 90% and 95-97%, respectively. The 10-year survival rate for AGCTs is approximately 76%. In contrast, the overall 5-year survival rate for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer is only 30-50% because only one quarter of patients present with stage I disease.

Recurrences in patients with AGCTs tend to be later than in patients with JGCTs. Mom et al reported a recurrence rate of 43% in 30 patients with stage I-III GCT observed over 10 years. Mom states that while the recurrence rate might be high, it falls within the range of 9-39% cited in other studies. [5] Average recurrence for the adult type is approximately 5 years after treatment, with more than half of these occurring more than 5 years after primary treatment. These tumors tend to follow an indolent course, with a mean survival of 5 years after the recurrence is diagnosed. The 10-year overall survival after an AGCT recurrence is in the 50-60% range.

More recently, van Meurs et al developed a prognostic model for the prediction of recurrence-free survival using BMI, clinical stage, tumor diameter, and mitotic index. [6] This model may provide useful information in the surveillance of AGCTs.

JGCTs recur much sooner, with more than 90% of recurrences occurring in the first 2 years. Recurrence in these patients is rapidly fatal.

Tumor stage at the time of initial surgery is the most important prognostic variable. Besides stage, Zhang et al found early stage disease and age younger than 50 years to be statistically significant factors in predicting survival. Other features associated with a poorer prognosis include high mitotic rates, moderate-to-severe atypia, preoperative spontaneous rupture of the capsule, and tumors larger than 15 cm. The presence of bizarre nuclei and tumor rupture intraoperatively does not appear to affect prognosis. [7] A study by Bryk et al reported tumor rupture as the strongest predictive factor for AGCT recurrence. [8]

Approximately 10% of tumors occur during pregnancy, but this does not affect prognosis. Perform surgical treatment for an adnexal mass in pregnancy early in the second trimester in order to minimize surgical and pregnancy risks.

True thecomas have an excellent prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of nearly 100%. However, their estrogen-producing capabilities may cause increased overall morbidity due to endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial adenocarcinoma, and possibly, breast carcinoma.

Morbidity/mortality

AGCTs and JGCTs have very good cure rates due to the early stage of disease at diagnosis. More than 90% of AGCTs and JGCTs are diagnosed before spread occurs outside the ovary. Five-year survival rates usually are 90-95% for stage I tumors compared to 25-50% for patients presenting with advanced-stage disease. Although 5-year survival rates are quite good, AGCTs have a propensity for late recurrence, some occurring as many as 37 years after diagnosis. Mean survival after the diagnosis of a recurrence is 5 years.

Approximately 20% of patients diagnosed with GCTs die of their disease over the course of their lifetime.

Morbidity related to GCTs primarily is due to endocrine manifestations of the disease. Physical changes brought on by high estrogen levels from the tumor usually regress upon removal of the tumor. However, a small group of patients present with symptoms of androgen excess from the tumor. Changes caused by androgen excess may be permanent or may only partially regress over time.

Serious estrogen effects can occur in various end organs. Unopposed estrogen production by these tumors has been shown to cause stimulation of the endometrium. Anywhere from 30-50% of patients develop endometrial hyperplasia and another 8-33% have endometrial adenocarcinoma. Patients also may be at an increased risk for breast cancer, although a direct correlation has been difficult to prove.

Complications

In 10-15% of cases, acute abdominal symptoms may be the presenting complaints for patients with rupture of their mass, hemorrhage into the mass, or torsion of the ovary.

Adverse effects from chemotherapy can be expected but generally are well tolerated. Specific adverse effects vary with the type of chemotherapy given (see Inpatient and Outpatient Medications for further detail).

Patient Education

Patients must be educated about the need for long-term follow-up, especially those with AGCTs. Early diagnosis and treatment can lead to prolonged survival in this group of patients.

For patient education resources, see the Women's Health Center and Cancer and Tumors Center, as well as Ovarian Cancer.

-

Microfollicular pattern of an adult granulosa cell tumor at 100X magnification. Inset is characteristic Call-Exner bodies and nuclear grooves (400X). Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.

-

Less well-differentiated diffuse pattern of adult granulosa cell tumor. Monotonous pattern can be confused with low-grade stromal sarcoma (200X). Inset is high-power magnification demonstrating nuclear grooves and nuclear atypia. Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.

-

Juvenile granulosa cell tumor. Multiple follicles in various shapes and sizes (200X). Inset shows nuclei that are rounded, hyperchromatic, lacking grooves and showing atypia, and are abnormal mitotic figures (400X). Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.

-

Gyriform pattern of adult granulosa cell tumor. Undulating single-file rows of granulosa cells (200X). Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.

-

Theca cell tumor. Typical thecoma with lipid-rich cytoplasm, pale nuclei, and intervening hyaline bands (200X). Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.

-

Luteinized thecoma. Vacuolated theca cells with an abundant fibromatous stroma (200X). Image courtesy of James B. Farnum, MD, TriHealth Department of Pathology.