Practice Essentials

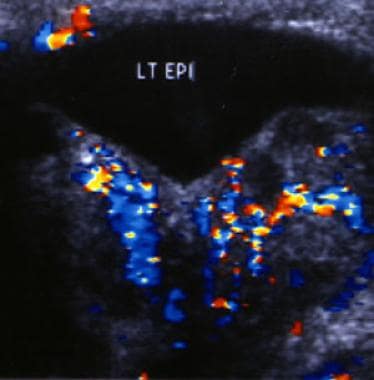

Epididymitis (inflammation of the epididymis; see the image below) is a significant cause of morbidity and is the fifth most common urologic diagnosis in men aged 18-50 years. [1] Epididymitis must be differentiated from testicular torsion, which is a true urologic emergency. [2]

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.

Signs and symptoms

The following history findings are associated with acute epididymitis and orchitis:

-

Gradual onset of scrotal pain and swelling, usually unilateral, often developing over several days (as opposed to hours for testicular torsion)

-

Dysuria, frequency, or urgency

-

Fever and chills (in only 25% of adults with acute epididymitis but in up to 71% of children with the condition)

-

Usually, no nausea or vomiting (in contrast to testicular torsion)

-

Urethral discharge preceding the onset of acute epididymitis (in some cases)

The following history findings are associated with chronic epididymitis:

-

Long-standing (>6 weeks) history of pain, either waxing and waning or constant

-

Scrotum that is not usually swollen but may be indurated in long-standing cases

The following history findings are associated with mumps orchitis:

-

Fever, malaise, and myalgia (common)

-

Parotiditis typically preceding the onset of orchitis by 3-5 days

-

Subclinical infections (30-40% of patients)

Physical examination findings may fail to distinguish acute epididymitis from testicular torsion. Physical findings associated with acute epididymitis may include the following:

-

Tenderness and induration occurring first in the epididymal tail and then spreading

-

Elevation of the affected hemiscrotum

-

Normal cremasteric reflex

-

Erythema and mild scrotal cellulitis

-

Reactive hydrocele (in patients with advanced epididymo-orchitis)

-

Bacterial prostatitis or seminal vesiculitis (in postpubertal individuals)

-

With tuberculosis, focal epididymitis, a draining sinus, or beading of the vas deferens

-

In children, an underlying congenital anomaly of the urogenital tract

Findings associated with orchitis may include the following:

-

Testicular enlargement, induration, and a reactive hydrocele (common)

-

Nontender epididymis

-

In 20-40% of cases, association with acute epididymitis

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The following laboratory studies may be indicated for suspected epididymitis:

-

Urinalysis: Pyuria or bacteriuria (50%); urine culture indicated for prepubertal and elderly patients

-

Complete blood count: Leukocytosis

-

Gram stain of urethral discharge, if present

-

Urethral culture, nucleic acid hybridization, and nucleic acid amplification tests to facilitate detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis

-

Performance of (or referral for) syphilis and HIV testing in patients with a sexually transmitted etiology

-

The use of C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to differentiate epididymitis from other causes of acute scrotum is under investigation

Although epididymitis may often be an infectious process, cultures commonly fail to demonstrate any identifiable infection.

Imaging studies that may be considered to evaluate structural abnormalities and help distinguish acute epididymitis from testicular torsion include the following:

-

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG)

-

Retrograde urethrography

-

Abdominal/pelvic ultrasonography

-

Radionuclide scanning and scintigraphy

-

In tuberculous epididymitis, chest radiography, computed tomography, or excretory urography

Other measures that may be useful for evaluation include the following:

-

Cystourethroscopy

-

Scrotal exploration or aspiration

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Pharmacologic treatment of epididymitis may include the following:

-

In chronic epididymitis, a 4- to 6-week trial of antibiotics effective against bacterial pathogens (especially chlamydiae)

-

When treating epididymitis secondary to Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae, treatment of all sexual partners

-

In prepubertal patients with epididymitis, antibiotic therapy only for young infants and those with pyuria or positive urine culture findings

In addition to antibiotics (except in viral epididymitis), the mainstays of supportive therapy for acute epididymitis and orchitis are as follows:

-

Reduction in physical activity

-

Scrotal support and elevation

-

Ice packs

-

Anti-inflammatory agents

-

Analgesics, including nerve blocks

-

Avoidance of urethral instrumentation

-

Sitz baths

Surgical options include the following:

-

Epididymotomy: Infrequently performed in patients with acute suppurative epididymitis

-

Epididymectomy: Typically reserved for refractory cases

-

Orchiectomy: Indicated only for patients with unrelenting epididymal pain

-

Skeletonization of the spermatic cord via subinguinal varicocelectomy: Performed in rare cases of refractory pain due to chronic epididymitis and orchialgia

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Go to Acute Epididymitis for complete information on emergent management of epididymitis.

Complications

Complications associated with acute epididymitis and bacterial orchitis include the following:

-

Scrotal abscess and pyocele

-

Testicular infarction: Cord swelling can limit testicular artery blood flow

-

Fertility problems

-

Testicular atrophy

-

Cutaneous fistulization from rupture of an abscess through the tunica vaginalis (seen especially in tuberculosis)

-

Recurrence, chronic epididymitis, and orchialgia

With regard to the last item above, true local pain can be distinguished from referred pain by spermatic cord injection with 1% lidocaine. Refractory pain that is not improved by analgesics has also been managed by denervation of the spermatic cord.

With regard to fertility problems, sterility is uncommon after acute epididymitis, although the true incidence is unknown. Disturbances in the sperm quality secondary to leukocytospermia and inflammation are usually transient. More important is the far less common azoospermia, which is caused by the epididymal duct obstruction observed in men with untreated or improperly treated epididymitis. The incidence of this condition is unknown.

Complications associated with mumps orchitis include the following:

-

Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism can occur as a result of testicular atrophy, which is observed in 30-50% of patients

-

Sterility occurs in 7-13% of affected patients; orchitis affects the testicular interstitium more than the Leydig and Sertoli cells, but sperm counts, mobility, and morphology can be affected

-

Orchialgia may develop

-

Mumps orchitis is not associated with the development of testicular tumors

Patient education

The patient should limit activity, and the scrotum should be immobilized.

Stress that the course of antibiotics needs to be completed, and also stress the need for screening tests for and treatment of comorbid sexually transmitted diseases for the patient and his sexual partners.

For patient education information, see Epididymitis.

Anatomy

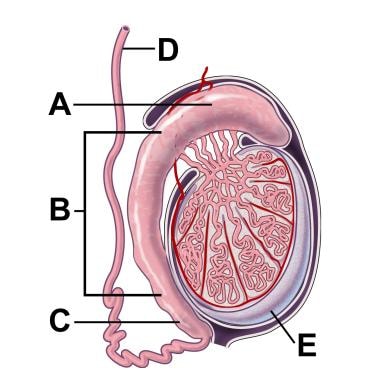

The epididymis is a coiled tubular structure located along the posterior aspect of the testis, connecting the efferent ducts of the testis to the vas deferens. It allows for the storage, maturation, and transport of sperm

The image below is a diagram of the testis and epididymis.

Cross-section illustration of a testicle and epididymis. A: Caput or head of the epididymis. B: Corpus or body of the epididymis. C: Cauda or tail of the epididymis. D: Vas deferens. E: Testicle. Illustration by David Schumick, BS, CMI. Reprinted with the permission of the Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art and Photography © 2009. All Rights Reserved.

Cross-section illustration of a testicle and epididymis. A: Caput or head of the epididymis. B: Corpus or body of the epididymis. C: Cauda or tail of the epididymis. D: Vas deferens. E: Testicle. Illustration by David Schumick, BS, CMI. Reprinted with the permission of the Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art and Photography © 2009. All Rights Reserved.

Etiology

The exact etiology of acute epididymitis is unclear; however, it is believed to be caused by the retrograde passage of urine from the prostatic urethra to the epididymis via the ejaculatory ducts and vas deferens. Obstruction of the prostate or urethra and congenital anomalies create a predisposition for reflux. Normally, the oblique angle of the ejaculatory ducts through the dense prostatic tissue prevents reflux. Fifty-six percent of men older than 60 years who have epididymitis exhibit concurrent bladder outlet obstruction (BOO), such as a urethral stricture or benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Reflux may also be induced by Valsalva maneuvers or strenuous exertion. This can be seen in athletes such as weight lifters. Epididymitis is commonly found to develop during strenuous exertion in conjunction with a full bladder.

Instrumentation and indwelling catheters are common risk factors for acute epididymitis.

Epididymitis may be accompanied by urethritis or prostatitis.

Acute epididymo-orchitis

Infection that is severe and extends to the adjacent testicle is termed acute epididymo-orchitis. [2] The etiology of acute epididymo-orchitis varies with the age of the patient and may be a bacterial, nonbacterial infectious, noninfectious, or idiopathic process.

Infections with urinary coliforms (eg, E coli, Pseudomonas species, Proteus species, Klebsiella species) are the most common cause in children and in men older than 35 years. Ureaplasma urealyticum, Corynebacterium species, Mycoplasma species, and Mima polymorpha have also been isolated. Systemic Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitides infections are rare. In men who are the insertive partner during anal intercourse, infections with coliform bacteria are also a common etiology. [3]

Chlamydia is the most common cause in sexually active men younger than 35 years (accounting for up to 50% of cases, although laboratory evidence of chlamydia may be absent in up to 90% of cases). [4] Infections with the following pathogens also occur in this population:

-

N gonorrhoeae

-

Treponema pallidum

-

Trichomonas species

-

Gardnerella vaginalis

Tuberculous epididymitis can occur in endemic areas and is still the most common form of urogenital tuberculosis (TB). It is believed to spread hematogenously and often involves the kidneys.

Epididymo-orchitis may develop following bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) treatment for superficial bladder cancer (at a rate of 0.4%).

Viral epididymitis is thought to be the predominant etiology of pediatric epididymitis. It is defined by the absence of pyuria. Although mumps is the most common viral cause of epididymitis, coxsackievirus A, varicella, and echoviral infections have also been identified.

Other rare infections (eg, brucellosis, [5] coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, cytomegalovirus [CMV], candidiasis, CMV in human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection, nontuberculous mycobacteria) have been implicated in epididymitis but usually occur in immunocompromised hosts.

Roughly 1 in 1000 men who undergo vasectomy describe a postvasectomy pain syndrome of chronic, dull, aching pain in the epididymis and testicle. The pain is most likely secondary to chronic epididymal congestion of sperm and fluid that continues to be produced after the vasectomy. The epididymis can become distended from back pressure of this fluid, particularly following the close-ended vasectomy technique. When sperm extravasates from the end of the vas deferens, such as can occur in the open-ended vasectomy technique, a sperm granuloma may develop, with a resulting inflammatory reaction.

Men older than 40 years may have BOO (eg, BPH) or a urogenital malformation that predisposes them to urethrovasal reflux and the development of epididymitis. Such reflux can also be induced iatrogenically after certain surgical procedures, such as transurethral resection of the ejaculatory ducts, resulting in epididymitis. It can also be a result of heavy physical activity such as weight lifting.

In children, infection is less common an etiology. One study of a pediatric emergency department found only 4 (4.1%) of 97 children diagnosed with epididymitis had a positive urine culture. [6] Children may have various congenital abnormalities or functional voiding problems that increase the risk of reflux into the ejaculatory ducts. For example, epididymitis may be related to urethral abnormalities, an ectopic ureter, an ectopic vas deferens, detrusor sphincter dyssynergia, or vesicoureteral reflux. In rare cases, children with anorectal malformations and resulting rectourinary fistulae may have resulting bacterial causes of epididymitis. [7]

Acute epididymo-orchitis has been described in 12-19% of individuals with Behçet syndrome. It is also associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura in the pediatric population, most likely as part of a systemic inflammatory process. Up to 38% of patients with Henoch-Schönlein have scrotal involvement (range, 2-38%).

Amiodarone epididymitis is secondary to high drug concentrations, usually in the head of the epididymis, and can occur in up to 3-11% of patients taking the drug. This is a dose-dependent phenomenon and typically occurs at dosages greater than 200 mg daily. Epididymal levels of the drug are up to 300 times those of the serum, resulting in antiamiodarone HCl antibodies that subsequently attack the epididymis, resulting in the symptoms of epididymitis. Histologic analysis reveals focal fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltration of epididymal tissues.

Sarcoidosis affects the genitourinary system in up to 5% of cases, typically presenting with epididymal nodules. Trauma to the scrotum can also be a precipitating event, while some cases are idiopathic.

Etiology of chronic epididymitis

The etiology of chronic epididymitis includes the following:

-

Inadequate treatment of acute epididymitis

-

Recurrent epididymitis

-

Association with a granulomatous reaction (most commonly Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

-

Association with a chronic disease process such as Behçet syndrome

Etiology of acute orchitis

Causes of acute orchitis include the following:

-

Viral: Mumps orchitis was once the most common etiology; however, since the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1985, this has been virtually eliminated

-

Bacterial and pyogenic infections: Infections with E coli, Klebsiella species, Pseudomonas species, Staphylococcus species, and Streptococcus species are unusual

-

Granulomatous: T pallidum, M tuberculosis, Mycobacterium leprae, Actinomyces, and fungal diseases are rare

-

Trauma

-

Idiopathic

With regard to a viral etiology, roughly one third of postpubertal boys with mumps have concomitant orchitis. Coxsackievirus type A, varicella, and echoviral, adenoviral, enteroviral, influenzal, and parainfluenzal infections are rare.

Epidemiology

An estimated 1 in 1000 men develop epididymitis annually, and acute epididymitis accounts for more than 600,000 medical visits per year in the United States. Epididymitis is the most common cause of intrascrotal inflammation. Incidence is less than 1 case in 1,000 males per year. However, chronic epididymitis may account for up to 80% of patients presenting with scrotal pain in the outpatient setting.

An Australian study of men aged 15 to 44 years found that in 2014, the emergency department (ED) incidence rate of epididymitis was 91.9 per 100,000 men, while the hospital admision rate for epididymitis was 38.7 per 100,000 men. Compared with 2009, those rates represented a 40% increase in ED presentation and a 32% increase in hospital admissions. [8]

Age-related demographics

Epididymitis is the fifth most common urologic diagnosis in men ages 18-50 years. The average age of a patient with chronic epididymitis is 49 years. Patients often experience symptoms for 5 years before diagnosis.

Acute epididymitis most commonly occurs in men aged 20-59 years (43% in men aged 20-39 y and 29% in men aged 40-59 y). Childhood (prepubertal) epididymitis is rare; testicular torsion is more common in this age group. [9]

In a study from Spain, epididymitis accounted for 28.4% of cases of acute, intense scrotal pain in adults presenting to an ED at one hospital. Orchiepididymitis comprised 28.7% of cases. The mean age of these patients was 40.2 ± 17.3 years. [10]

Structural urologic abnormalities are common in children and in men older than 40 years with acute epididymitis. Adults usually have BOO or urethral stricture or may have had previous urologic surgery on their urethra, altering their anatomy and predisposing them to infection. Children may have urethral abnormalities, such as a prostatic utricle, urethral duplication, posterior urethral valves, or urethrorectal fistula, or other anomalies, such as an ectopic ureter, ectopic vas deferens, detrusor sphincter dyssynergia, or vesicoureteral reflux.

Siegel et al found that 47% of prepubertal boys with epididymitis had associated urogenital abnormalities, including ectopic vas deferens or ureters, and urethral abnormalities. [11]

Mumps orchitis occurs in 20-40% of postpubertal boys with mumps but is rare in prepubertal boys.

Prognosis

Hongo et al reported that older age; previous history of diabetes mellitus and fever; and higher white blood cell count, C-reactive protein level, and blood urea nitrogen level were independently associated with severity in Japanese patients with epididymitis. These authors created an algorithm that proved to have 98.8-100% specificity for predicting severe epididymitis. [12]

Pain improves within 1-3 days, but induration may take several weeks or months to resolve. Infection of the epididymis can lead to the formation of an epididymal abscess. In addition, progression of the infection can lead to involvement of the testicle, causing epididymo-orchitis or a testicular abscess. Sepsis is a potential consequence of severe infection. Bilateral epididymitis may result in sterility due to occlusion of the ductules from peritubular fibrosis.

Patients with epididymitis secondary to a sexually transmitted disease have 2-5 times the risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV. [13] All sexual partners of patients with epididymitis secondary to a sexually transmitted disease need referral to ensure that they receive adequate testing and treatment.

-

Cross-section illustration of a testicle and epididymis. A: Caput or head of the epididymis. B: Corpus or body of the epididymis. C: Cauda or tail of the epididymis. D: Vas deferens. E: Testicle. Illustration by David Schumick, BS, CMI. Reprinted with the permission of the Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art and Photography © 2009. All Rights Reserved.

-

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.

-

Scrotal sonogram demonstrating the presence of a hydrocele and an enlarged epididymis in a patient with epididymitis. The echogenic white area is the normal testicle surrounded by the hydrocele.

-

Scrotal sonogram showing the testes adjacent to the inflamed epididymis with a reactive hydrocele.