Practice Essentials

Fecal incontinence is a syndrome that involves the unintentional loss of solid or liquid stool. Many definitions of fecal incontinence exist, some of which include flatus (passing gas), while others are confined to stool. [1]

True anal incontinence is the loss of anal sphincter control leading to the unwanted or untimely release of feces or gas. This must be distinguished from other conditions that lead to stool passing through the anus. Stool seepage that produces soilage of undergarments may result from hemorrhoids, enlarged skin tags, poor hygiene, fistula-in-ano, and rectal mucosal prolapse. Other conditions that result in poor bowel control are inflammatory bowel disease, laxative abuse, parasitic infection, and toxins. Fecal urgency also must be differentiated from fecal incontinence because urgency may be related to medical problems other than anal sphincter disruption.

Diagnosis

History and physical examination

The history should include a thorough account of the type and duration of fecal incontinence, frequency of incontinent episodes, type of stool lost, impact of the disorder on the patient's life, history of associated trauma or surgery, and associated factors such as protective undergarment use. In addition, an obstetric history should be obtained.

A focused physical examination should be performed. After inspection, sensation of the perianal region should be assessed. Digital examination should be performed to detect obvious anal pathology and provide an initial assessment of the anal resting tone.

Imaging studies

The standard diagnostic imaging study for the anal sphincters is transanal or endoanal ultrasonography. See the image below.

Fecal incontinence. Ultrasound taken with the patient in the low lithotomy position showing a defect in the internal anal sphincter at the level of the puborectalis muscle that can be seen as a U-shaped echogenic mass posteriorly.

Fecal incontinence. Ultrasound taken with the patient in the low lithotomy position showing a defect in the internal anal sphincter at the level of the puborectalis muscle that can be seen as a U-shaped echogenic mass posteriorly.

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnostic procedures used in the workup of fecal incontinence include the following:

-

Anal manometry

-

Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency

-

Electromyelography

-

Defecography (evacuation proctography)

See Workup for more detail.

Treatment

Conservative treatment options for fecal incontinence include bulking agents and biofeedback. The goal of medical therapy is to reduce stool frequency and improve stool consistency.

Once medical therapy has been maximized, minimally invasive therapies, such as sacral nerve stimulation, and surgical therapies may be considered. In select patients, injectable materials may improve anal sphincter function.

Several surgical procedures are performed for the treatment of anal incontinence. The standard procedure for incontinence due to anal sphincter disruption is the anterior overlapping sphincteroplasty.

See Treatment for more detail.

Background

Fecal incontinence is one of the most psychologically and socially debilitating conditions in an otherwise healthy individual. It can lead to social isolation, loss of self-esteem and self-confidence, and depression. This article is devoted to the problem of fecal incontinence in the adult female patient. [2]

In 2015, summaries of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, classification, and treatment of fecal incontinence were published from the 2013 National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Workshop. [3, 4]

Pathophysiology

Bowel function is controlled by multiple factors including anal sphincter pressure, anorectal sensation, rectal compliance, colonic transit time, and stool volume and consistency. In addition, adequate cognitive function with appropriate ability to access bathroom facilities are necessary for continence. If any of these factors are compromised, incontinence can occur.

Fecal continence is maintained by the structural and functional integrity of the anorectal unit. Normal anal sphincter function is a critical part of continence. The anal sphincter is comprised of 2 components: the internal anal sphincter (IAS), which is a 0.3-0.5 cm expansion of the circular smooth muscle layer of the rectum and the external anal sphincter (EAS), a 0.6-1.0 cm expansion of the levator ani muscles. The IAS is chiefly responsible for maintaining continence at rest and contributes approximately 70-80% of the resting sphincter tone. This barrier is reinforced during voluntary squeeze by the EAS, the anal mucosal folds, and the anal endovascular cushions.

These barriers are further augmented by the puborectalis muscle, which forms a sling around the rectum and creates a forward pull to reinforce the anorectal angle. The anorectal angle, which is approximately 90 degrees at rest, is created as the rectum perforates the levator complex. During voluntary squeeze, the angle becomes more acute, whereas during defecation, the angle becomes more obtuse. Innervation of the EAS is from the pudendal nerve, a mixed motor and sensory nerve that arises from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves (S2, S3, and S4). Innervation of the puborectalis arises more directly from the sacral nerves listed above. [5]

Continence requires the complex integration of signals among the smooth muscle of the colon and rectum, the puborectalis muscle, and the anal sphincters. As colonic contents are presented to the rectum, the rectum distends. The sensation of rectal distension is most likely transmitted along the S2, S3, and S4 parasympathetic nerves. This results in a parasympathetically mediated relaxation of the IAS (rectoanal inhibitory reflex) and a contraction of the EAS (rectoanal contractile reflex).

Rectal contents are allowed to come into contact with the very sensitive epithelial lining of the upper anal canal. The epithelial lining of the upper anal canal has a rich supply of sensory nerve endings, especially in the region of the anal valves. The contents are then sampled as to their nature (ie, gas, liquid, or solid). This sampling is described as an equalization of the rectal and upper anal canal pressures. Miller et al found that sampling occurred spontaneously in 16 of 18 control patients but in only 6 of 18 incontinent patients. Similarly, Miller's study demonstrated that patients with impaired continence had decreased thermal and electrical sensitivity to stimuli. [6] The decreased anorectal sensation and abnormal sampling likely contribute in the pathogenesis of anal incontinence as sampling facilitates the fine tuning of the continence barrier. This process is incompletely understood. [5, 7]

When defecation is desired, the anorectal angle straightens (which is facilitated by squatting or sitting), and abdominal pressure is increased by straining. This results in descent of the pelvic floor, contraction of the rectum, inhibition of the external anal sphincter, and subsequent evacuation of the rectal contents.

If evacuation of the rectum is not socially appropriate, sympathetically mediated inhibition of the smooth muscle of the rectum and voluntary contraction of EAS and puborectalis musculature occur. The anorectal angle becomes more acute and prevents the bolus of stool from descending further. The contents of the rectum are forced back into the compliant rectal reservoir above the levators, which allows the IAS to recover and contract again. A decrease in the compliance of this rectal reservoir has been associated with fecal urgency and anal incontinence. The exact mechanism of this is unclear and debate continues as to whether it is a cause or result of anal incontinence.

In essence, any process that interferes with these mechanisms, including trauma from vaginal delivery or a neurological insult, can result in fecal incontinence.

A 2015 summary of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and classification of fecal incontinence from the 2013 National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Workshop has been published. [3]

Etiology

Fecal incontinence has many etiologies. One or a combination of several factors can lead to the inability to control passage of stool or flatus. Congenital abnormalities such as spina bifida and myelomeningocele with resultant spinal cord damage can result in fecal incontinence. Inflammatory bowel disease may lead to decreased compliance of the rectum and may manifest as fecal urgency, frequency, soilage, or incontinence. Anal surgery, such as hemorrhoidectomy and sphincterotomy, has been associated with internal sphincter injury and subsequent urgency and incontinence. [8]

Medical conditions that may result in fecal incontinence include diabetes mellitus, stroke, spinal cord trauma, and degenerative disorders of the nervous system. These conditions may alter normal sensation, feedback, or function of the complex mechanism of anal continence. The patient's ambulatory status is also important when considering the etiology of the disorder. Wheelchair-bound patients and those who are dependent on others for access to bathroom facilities may have episodes of functional incontinence, yet have completely normal anorectal function.

Vaginal delivery is widely accepted as the most common predisposing factor to fecal incontinence in an otherwise young and healthy woman. [9] Vaginal delivery may result in internal or external anal sphincter disruption, or may cause more subtle damage to the pudendal nerve through overstretching and/or prolonged compression and ischemia.

Many studies support the theory that mechanical sphincter disruption contributes to fecal incontinence. [10] Abramowitz et al found a de novo sphincter defect rate of 16.7% after vaginal delivery (14% with external, 1.7% internal, and 1% both). The overall anal incontinence rate was 9%, and 45% of these women had identifiable sphincter defects on anal endosonography. [11]

In addition, inadequate repairs of obstetric sphincter injuries may contribute to delayed symptoms of fecal incontinence. In a study of 34 women who sustained third-degree obstetric anal sphincter tears and 88 matched controls, Sultan et al found that approximately half the women (47%) who sustained a third-degree tear experienced some impairment of anal continence despite a primary repair. Anal pressures were significantly lower, but pudendal nerve terminal motor latency measurements were not different. They relate the cause as a persistent mechanical sphincter disruption rather than pudendal nerve damage. [12]

Similarly, Nielsen et al found that 13 of 24 (54%) patients who underwent primary repair for sphincter disruption at the time of delivery demonstrated external sphincter defects at 3- and 12-month follow-up. Tetzschner et al found that 18 of 94 (19%) of women who sustained obstetric anal sphincter rupture had fecal incontinence shortly after delivery. [13] A follow-up study by the same group demonstrated that 30 of 72 (42%) women who had sustained an obstetric anal sphincter rupture had fecal incontinence at 2-4 years postpartum. [14] Factors that are significantly associated with an increased risk of third-degree obstetric sphincter tears are primiparity, occiput posterior presentation, use of forceps, fetal weight greater than 4000 g, perineal tears, episiotomy, and prolonged second stage of labor. [12, 15]

Pudendal nerve injury may also be a mechanism in fecal incontinence. The pudendal nerve innervates the external anal sphincter muscle, anal canal skin, and coordinates reflex pathways. Evidence of neurologic damage from the forces of labor is illustrated in a study by Fynes et al, who evaluated anorectal physiology in women undergoing cesarean delivery at different stages of labor. They found that anorectal function was unaltered in women undergoing cesarean delivery early in labor. In women with advanced cervical dilation (>8 cm) at the time of cesarean delivery, they found delayed pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) and reduced anal squeeze pressures. [16]

In the Tetzschner study of women who sustained obstetric anal sphincter rupture during vaginal delivery, postpartum fecal incontinence was also associated with delayed PNTML of greater than 2.0 milliseconds. [13] This type of neurologic injury was confirmed in a recent large study. In 923 patients with fecal incontinence (745 women), 56% demonstrated pudendal neuropathy (38% were unilateral). Neuropathy was associated with decreased anal resting tone and squeeze pressures. [17] Similarly, Allen et al found that 80% of patients had electromyelogram (EMG) evidence of nerve damage after their first vaginal delivery, particularly if they had a long second stage of labor or delivered larger infants. [18]

Successive vaginal deliveries increase the risk of developing fecal incontinence. Sultan et al demonstrated that 35% of primiparous women and 44% of multiparous women had sphincter disruption after delivery but were asymptomatic. In this same study, 13% of primiparous patients and 23% of multiparous patients undergoing vaginal delivery complained of fecal incontinence or fecal urgency at 6 weeks postpartum. Symptoms are worse if a patient has had damage to the sphincter in a prior delivery or was symptomatic with anal incontinence previously. Ryhammer et al found a significant long-term association between the number of vaginal deliveries and several anorectal parameters in perimenopausal women. They noted lower perineal position at rest, increased perineal descent with maximal straining, decreased anal sensibility to electrical stimulus, and prolonged latency in pudendal nerves to be associated with increasing parity. [19]

In recent years, national attention has been focused on the risks and benefits of cesarean delivery prior to labor and its impact on pelvic floor health. However, the literature is divided as to whether cesarean delivery is protective against fecal incontinence.

In a population-based Oregon study from 2009 of 5491 primiparous women, nearly half (45.2%) experienced a new onset of at least 1 symptom of fecal incontinence in the survey period of 3-6 months after delivery. Among these women with fecal incontinence, 46% reported incontinence of flatus only, 22.8% were incontinent of liquid stool, and 18% were incontinent of solid stool. Vaginal delivery was associated with a greater risk of fecal incontinence compared with cesarean section (OR=1.45). However, vaginal delivery without laceration of instrument assistance did not increase the risk of fecal incontinence over cesarean. Interestingly, cesarean was not completely protective against fecal incontinence, given that 38% of women who delivered by cesarean without labor or pushing reported new-onset symptoms of fecal incontinence. [20]

Age may also play a role in the development of fecal incontinence. Haadem et al evaluated 49 continent, healthy women with a mean age of 51 years (range, 20-79 y). Anal manometry studies showed a decrease in maximum anal resting pressure and maximum squeeze pressure that was associated with age, irrespective of parity. These findings were more pronounced after menopause, suggesting a role for estrogen in the mechanism of this disorder. [21] Similar findings of decreased anal pressures on manometry results were reported by Bannister et al, who also found that aging resulted in lower rectal volumes needed to inhibit anal sphincter tone. [22]

When evaluating the effects of aging on anorectal sphincters, Laurberg and Swash found no significant changes in resting anal pressure. However, in women older than 50 years, they found that anal canal squeeze pressure was significantly lower compared with that found in younger women. [23] Johanson and Lafferty found that the prevalence rate of fecal incontinence in individuals younger than 30 years was 12.3%, compared with 19.4% in those older than 70 years. Approximately 56% of psychogeriatric patients and 32% of geriatric patients in long-term care facilities are anally incontinent on a regular basis. Increasing age is also associated with slowed pudendal nerve conduction, perineal descent at rest, and decreased anorectal sensory function. [24]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Exact data on the prevalence of fecal incontinence are difficult to obtain. This is partly because patients are reluctant to volunteer information about their condition to their health care provider. Fewer than 30% of women with fecal incontinence seek medical attention. [25] Conversely, heath care providers are not diligent about soliciting symptoms during maintenance visits. In addition, the definition (incontinence of solid stool, diarrhea or flatus) and frequency of fecal incontinence vary greatly in each study population.

The reported prevalence of fecal incontinence in the general population is approximately 2-3%. [26] Nelson et al found a prevalence rate of 2.2% among community-dwelling persons in the state of Wisconsin. In their study, 6959 individuals were surveyed and 30% of the individuals were older than 65 years and 63% were women. [26] In another study, Johanson and Lafferty observed an overall prevalence rate of 18.4% among individuals at the time of visit to their primary care physician or gastroenterologist. [27] Only one third of the group had ever discussed the problem with a physician. However, in this study, any involuntary loss of stool or soiling was considered to be incontinence; therefore, patients with soilage for reasons other than true incontinence may have been included. In the nursing home setting, the prevalence of fecal incontinence approaches 50% and can be a primary cause for admission. [28]

Rates of fecal incontinence in women have been investigated, both in the immediate and remote postpartum period. At 3-6 months after vaginal or cesarean delivery, as many as 13-25% of women report fecal incontinence. [29] In a population-based, postnatal survey of 6000 women (age 30-90 y), the prevalence of fecal incontinence (defined as at least monthly loss of liquid or solid stool) was 7.2%. Older age, major depression, urinary incontinence, medical comorbidity, and operative vaginal delivery were significantly associated with increased odds of fecal incontinence. [30, 31]

Nygaard et al evaluated the prevalence of anal incontinence 30 years postpartum in 3 groups of women. One group had disruption of the anal sphincter with vaginal delivery, the second group had an episiotomy without disruption of the anal sphincter, and the third group delivered by cesarean. They found no significant difference in the frequency of flatus incontinence among the 3 groups, at a rate of 30-40%. However, the number of women with bothersome flatus incontinence was higher in the sphincter disruption group (58%) compared with 30% of the episiotomy group and 15% of the cesarean group. The percentage of bothersome fecal incontinence was similar among the 3 groups at about 20%. [32]

The financial cost of fecal incontinence is significant. More than $400 million is spent each year for adult diapers that control urinary and fecal incontinence. It is the second leading cause of admission to long-term care facilities in the United States. In younger patients who desire treatment and correction, the costs are surprisingly high. In a 1996 study of 63 patients treated for fecal incontinence secondary to obstetric injuries, the average cost of treatment per patient was $17,166. [33] Approximately 21,000 women underwent inpatient surgery for fecal incontinence between 1998 and 2003 (approximately 3500 women per year). Total charges gradually increased from $34 million in 1998 to $57.5 million in 2003. The mean cost per surgical admission in 2003 was $16,847. [34]

Presentation

Patients who present for evaluation of fecal incontinence usually have had to overcome extreme embarrassment over their condition prior to their office visit. Care should be given to the manner in which the topic is approached in order to promote an open and comfortable discussion.

The history should include a thorough account of the type and duration of fecal incontinence, frequency of incontinent episodes, type of stool lost, impact of the disorder on the patient's life, history of associated trauma or surgery, and associated factors such as protective undergarment use. True incontinence must be differentiated from pseudoincontinence, and patients may perceive drainage of mucous, pus, or blood from the perianal region as incontinence. Medications and dietary habits should be reviewed to determine if an easily remedied cause exists. A review of systems for systemic medical conditions that contribute to fecal incontinence is important and should be elicited.

An obstetric history should be taken carefully. Information about the number of vaginal deliveries and the presence of any risk factors for fecal incontinence pertaining to those deliveries should be obtained. As previously mentioned, prolonged second stage of labor, forceps delivery, significant tears, and episiotomy, among other causes, are associated with increased risk for anal sphincter disruption and pudendal nerve injury.

Several fecal incontinence surveys attempt to quantify and qualify the severity of fecal incontinence. Two examples are the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale produced by Rockwood et al and the Fecal Incontinence Questionnaire by Reilly et al. [35, 36] The forms are largely designed as outcome measures and are most useful in a research setting. The benefit to the practitioner not in a research environment is that a great deal of information about patient symptoms and the impact of those symptoms can be obtained in a short period of time.

Once a complete history has been obtained, a focused physical examination should be performed. Practitioners who routinely perform physical examinations on female patients should be familiar with normal perineal, vaginal, and anal sphincter anatomy. The examination should consist of a careful visual inspection of the perineal body and anus. The vagina should be inspected with the aid of a speculum. Examination of the anal region may reveal skin tags, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, scars, or chemical dermatitis. Rectal prolapse or fistulae may also be present.

After obstetric injuries, a discrete sphincter defect will almost always be anterior in location and be associated with loss of the perineal body or attenuation of the rectovaginal septum. Sometimes, however, the connective tissue of the perineal body is intact and only the sphincter has failed to heal. With an intact anal sphincter, the creases in the anal skin are arranged radially around the anal canal. When the sphincter is disrupted and the perineal skin is intact, there is a classic dovetail appearance to the anus, in which the radial distribution of the anal skin creases is absent anteriorly. [37]

After inspection, sensation of the perianal region should be assessed. This is performed by gently stroking the skin surrounding the anus and observing a reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter. The absence of this anocutaneous reflex suggests interruption of the spinal arc.

Digital examination should be performed to detect obvious anal pathology and provide an initial assessment of the anal resting tone. As the provider is beginning the rectal examination, resistance is met at the anal verge. If the examining finger meets little resistance and the anus feels patulous, significant sphincter dysfunction may be present. Deformity may be due to fistulotomy, fissurectomy, or hemorrhoidectomy.

A bimanual digital rectal examination is performed using 1 digit in the rectum and 1 digit in the vagina. This examination is mandatory to palpate the anal sphincters, determine perineal body thickness, evaluate anal sphincter and levator tone, and test for perineal body hypermobility. The external anal sphincter is palpable as a 1.5-2 cm, moderately firm, doughnut-shaped mass within the perineal body. If, upon palpation of the perineal body, the examining fingers are not separated by much tissue or the muscle mass is not palpated, damage to the anal sphincter is likely. Palpation from a midline position laterally helps to define where normal muscle exists. These findings can be subtle and may require some degree of experience to elicit.

The patient is asked to tighten the sphincter around the examining finger. A circumferential increase in the pressure should be felt. Patients who have a disrupted anal sphincter may have adequate innervation to the existing muscle bellies, and equal pressure may be felt on the examining finger. Evaluating the nature and location of increases in muscle tone is important. Pressure may be placed on the finger laterally from existing functional muscle, but no or very little pressure may be felt anteriorly. Disruption of the muscle sphincter allows the muscle bellies to retract laterally and posteriorly, similar to the ends of a rubber band that is cut after being placed on gentle stretch. Scar tissue may develop anteriorly between the 2 ends of muscle and, with contraction of the lateral muscle bellies, gives the impression of an intact anal sphincter. Palpation of the muscle can assist in this situation.

During rectal examination, the tip of the examining finger is gently flexed and traction is placed on the perineal body. The perineal body is normally supported by the perineal membrane (urogenital diaphragm), which originates from the ischiopubic rami bilaterally. The perineal membrane, along with other fascial supports, inhibits the caudad displacement of the perineal body. Birth trauma sufficient enough to result in detachment or tearing of this support also may have resulted in damage to the anal sphincters, and this history finding may prompt further questioning and evaluation.

Although the physical examination is a standard part of any evaluation for fecal incontinence, there is no exact correlation between digital assessment of sphincter tone and contractility. Physical examination results have also been noted to conflict with anal manometry.

Indications

Indications for surgical repair for fecal incontinence are largely based on physical findings and the degree to which the patient is symptomatic. Surgical repair of the anal sphincter is not without potential complications and discomfort. Importantly, the physician should counsel the patient about the risks of the procedure and the potential for recurrence.

Examination may reveal a sphincter defect that is discovered in association with other defects in pelvic support. The patient may be asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic for anal incontinence. Whether surgical repair should be performed in this situation is controversial and must be a decision reached between the patient and the physician. The evidence presented suggesting that age alone is a risk factor for the development of anal incontinence must be factored into the equation if a known anatomic defect is present. Clearly, this type of patient is at increased risk of anal incontinence in the future. Additionally, surgical outcomes of sphincter repair have been shown to be poorer in older women.

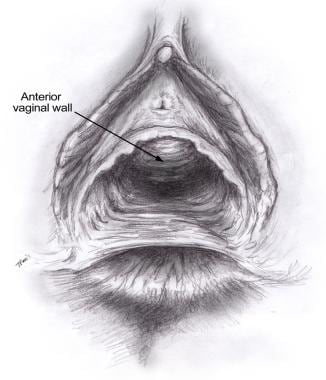

Relevant Anatomy

A clear understanding of anatomy is mandatory for any surgical procedure, including surgical procedures of the perineum and anal sphincter. The perineal body is composed of a fusion of several structures. The Denonvilliers fascia is fused, which serves to suspend the perineal body from the sacrum via the endopelvic fascia. The bulbospongiosus and superficial transverse perineum muscles insert onto the perineal body. The bulbospongiosus originates from the pubic rami and inserts into the anterior aspect of the central tendon of the perineum. The superficial transverse perineum muscle originates on the ischial tuberosities and approaches the perineal body from a lateral position. The perineum is innervated by the labial nerve and inferior rectal nerve, which are branches of the pudendal nerve. The external anal sphincter is fused to the perineal body more posteriorly.

See the image below.

An attenuated perineal body results from trauma to the perineum and damage to the structures that normally compose the perineal body.

An attenuated perineal body results from trauma to the perineum and damage to the structures that normally compose the perineal body.

The anatomy of the external anal sphincter continues to be debated. Some suggest that it composed of 3 parts that are fused, while others maintain that it is composed of 2 more distinct parts. A subcutaneous portion (just deeper than the perineal skin), a superficial portion, and a deep portion exist. Some combine the subcutaneous and superficial components into a single component. The separation of these components is indistinct in a surgical repair. The deep portion of the external anal sphincter is fused to the puborectalis muscle of the levator complex, and some even suggest that it is a continuation of it. It receives innervation from the pudendal nerve.

The internal anal sphincter is a continuation of the inner circular smooth muscle of the bowel wall. This musculature thickens over the last 2.5-4 cm of the rectum. The internal anal sphincter lies deep to the external anal sphincter, and an identifiable and surgically important plane exists between them. The internal anal sphincter begins at the level of the levator complex, and its distal extent is just proximal to the subcutaneous portion of the external sphincter. The internal anal sphincter is supplied by the autonomic nervous system. It exists in a state of continuous maximal contraction and provides a barrier to the involuntary loss of stool.

The levator complex is composed of the pubococcygeus, the iliococcygeus, and the coccygeus muscles. The most medial fibers of the pubococcygeus make up the puborectalis. These fibers loop around the posterior aspect of the rectum and create an anterior displacement of the rectum known as the anorectal angle. The pelvic surface of the levator complex is innervated by sacral efferents from S2 through S4. The inferior surface is supplied by the perineal and inferior rectal branches of the pudendal nerve. Consequently, pudendal block does not abolish voluntary contraction of the pelvic floor but completely abolishes external anal sphincter function. [5]

Contraindications

Contraindications to surgery for anal incontinence occur when the etiology for incontinence is uncertain; when a nonsurgical therapy, such as medication or diet alteration, would provide relief of symptoms; a woman is pregnant; or when surgical repair would place the patient at risk for complications from other medical conditions.

-

Fecal incontinence. External anal sphincter showing normal narrowing anteriorly.

-

Fecal incontinence. Ultrasound of mid anal canal taken with the patient in the low lithotomy position showing intact internal and external anal sphincters.

-

Fecal incontinence. Internal anal sphincter at the level of the levators. The levators are demonstrated by the U-shaped echogenic band posteriorly.

-

Fecal incontinence. External anal sphincter from a nulliparous patient showing the normal anterior narrowing seen in women.

-

Fecal incontinence. Ultrasound of the external anal sphincter taken with the patient in the low lithotomy position showing a defect from the 9- to the 3-o'clock position. The picture also shows the superficial transverse perineum muscles entering from lateral positions.

-

Fecal incontinence. Ultrasound taken with the patient in the lithotomy position, at the mid anal canal, showing an internal anal sphincter defect from the 10- to the 2-o'clock position.

-

Fecal incontinence. Ultrasound showing an internal anal sphincter defect.

-

Fecal incontinence. Ultrasound taken with the patient in the low lithotomy position showing a defect in the internal anal sphincter at the level of the puborectalis muscle that can be seen as a U-shaped echogenic mass posteriorly.

-

An attenuated perineal body results from trauma to the perineum and damage to the structures that normally compose the perineal body.

-

The InterStim® System neurostimulator manufactured by Medtronic shown in place. Courtesy of Medtronic Inc.

-

The InterStim® System neurostimulator manufactured by Medtronic. Courtesy of Medtronic Inc.

-

Eclipse System (vaginal insert) from Pelvalon. Courtesy of Pelvalon Inc.