Practice Essentials

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States and is the leading cause of death in persons aged 1-44 years, with approximately 2 million traumatic brain injuries occurring each year. A National Institutes of Health survey estimates that 1.9 million persons annually experience a skull fracture or intracranial injury. Firearms account for the largest proportion of deaths from traumatic brain injury in the United States; each year, close to 20,000 persons have gunshot wounds to the head. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] The definition of a penetrating head injury (pTBI) is a wound in which a projectile breaches the cranium but does not exit it. The morbidity and mortality associated with penetrating head injury remain high. Analysis of the trauma literature has shown that 50% of all trauma deaths are secondary to TBI, and gunshot wounds to the head caused 35% of these.

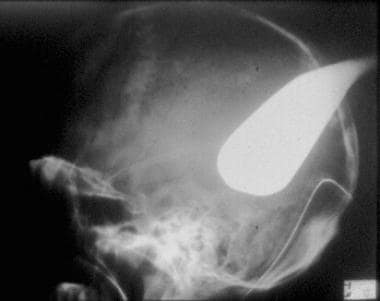

(The CT scan below is of a patient after a gunshot wound to the brain.)

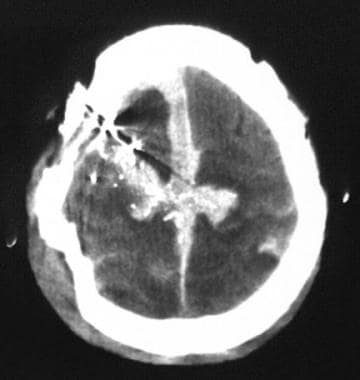

A young man arrived in the emergency department after experiencing a gunshot wound to the brain. The entrance was on the left occipital region. A CT scan shows the skull fracture and a large underlying cerebral contusion. The patient was taken to the operating room for debridement of the wound and skull fracture, with repair of the dura mater. He was discharged in good neurological condition, with a significant visual field defect.

A young man arrived in the emergency department after experiencing a gunshot wound to the brain. The entrance was on the left occipital region. A CT scan shows the skull fracture and a large underlying cerebral contusion. The patient was taken to the operating room for debridement of the wound and skull fracture, with repair of the dura mater. He was discharged in good neurological condition, with a significant visual field defect.

Penetrating head injuries can be the result of numerous intentional or unintentional events, including missile wounds, stab wounds, and motor vehicle or occupational accidents (nails, screwdrivers). Stab wounds to the cranium are typically caused by a weapon with a small impact area and wielded at low velocity. The most common wound is a knife injury, although bizarre craniocerebral-perforating injuries have been reported that were caused by nails, metal poles, ice picks, keys, pencils, chopsticks, and power drills. [7, 8]

In a study of 14 children with intracranial injuries due to spring- or gas-powered BB or pellet guns, 10 of the children required surgery, and 6 were left with permanent neurologic injuries, including epilepsy, cognitive deficits, hydrocephalus, diplopia, visual field cut, and blindness. According to the study authors, advances in compressed-gas technology have led to a significant increase in the power and muzzle velocity of such guns, with the ability to penetrate a child's skull and brain. [9]

Siccardi et al prospectively studied a series of 314 patients with craniocerebral missile wounds and found that 73% of the victims died at the scene, 12% died within 3 hours of injury, and 7% died later, yielding a total mortality of 92% in this series. [10] In another study, gunshot wounds were responsible for at least 14% of the head injury-related deaths. [1] A study using multiple logistic regressions found that injury from firearms greatly increases the probability of death and that the victim of a gunshot wound to the head is approximately 35 times more likely to die than is a patient with a comparable nonpenetrating brain injury. [11]

Evaluation

The assessment of patients with penetrating brain injuries should include routine laboratory tests, electrolytes, and coagulation profile. Many patients have lost a significant amount of blood before reaching the emergency department or might present with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC); consequently, determining the hemoglobin concentration and platelet count is important. Type and cross match should always be obtained with the initial orders. Obtaining a toxicology screen, including alcohol levels, is also appropriate.

The radiologic methods of evaluation depend on the patient's condition. In general, a lateral cervical spine and chest radiographs are obtained in the resuscitation room. A CT scan of the head should be obtained as soon as the patient's cardiopulmonary condition has been stabilized to determine the extent of intracranial damage and the presence of intracranial metallic fragments. The study always should include bone windows to evaluate for fractures, especially when the skull base or orbits are compromised. Some centers can perform CT angiography (CTA) for the evaluation of intracranial and extracranial vessels. Multidetector-row CTA has improved the detectability of both vascular and extravascular injuries in patients with penetrating injuries. [2, 12, 13, 14]

If a vascular injury is suspected and the patient is stable, cerebral angiography often is used to diagnose injuries such as carotid and/or vertebral artery dissections, traumatic pseudoaneurysms, or arteriovenous fistulas.

In patients with penetrating injuries and intracranial metallic fragments, an MRI scan is contraindicated. If the presence of bullets or intracranial metallic fragments has been ruled out, an MRI scan of the brain provides valuable information on posterior fossa structures and the extent of sharing injuries.

A fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence allows the evaluation of contusions or hemorrhages.

Diffusion or perfusion scan sequences are useful to evaluate areas of stroke or cerebral ischemia.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and magnetic resonance venogram (MRV) are useful if vascular or sinus injuries are suspected.

Treatment

Patients with severe penetrating injuries should receive resuscitation according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines. Specific indications for endotracheal intubation include inability to maintain adequate ventilation, impending airway loss from neck or pharyngeal injury, poor airway protection associated with depressed level of consciousness, and/or the potential for neurologic deterioration. Virtually all individuals with an admission Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 8 or less meet these criteria. [15, 16, 6, 6]

The cervical spine is stabilized, and a careful examination for injuries to the neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis, and extremities is performed. A Foley catheter should be inserted, appropriate IV access secured, and volume replacement started.

If pharmacologic paralytic agents were administered during resuscitation, these agents should be reversed in order to complete the neurologic examination. Tetanus prophylaxis is administered.

Propofol, a lipophilic rapid-onset hypnotic with a short half-life that can be titrated to control ICP.

Mannitol administered as intravenous bolus as needed results in decreased ICP; it reduces the viscosity of blood, improving cerebral blood flow; and it might serve as a free-radical scavenger.

If the ICP cannot be controlled, barbiturate coma or a decompressive craniectomy may be indicated.

Additional routine orders include seizure prophylaxis (phenytoin 15-18 mg/kg IV bolus followed by 200 mg IV q12h) and antibiotics. [17]

The following are significant reasons for surgery: (1) to remove masses such as epidural, subdural, or intracerebral hematomas; (2) to remove necrotic brain and prevent further swelling and ischemia; (3) to control an active hemorrhage; and (4) to remove necrotic tissue, metal, bone fragments, or other foreign bodies to prevent infections.

Epidemiology

A National Institutes of Health survey estimates that in the United States, 1.9 million persons annually experience a skull fracture or intracranial injury, and of these cases, 50% have a suboptimal outcome. Firearms account for the largest proportion of deaths from traumatic brain injury in the United States. Each year close to 20,000 persons in the United States are involved in gunshot wounds to the head. [2, 3]

Every year, at least 1.7 million traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) occur in the United States, and they are a contributing factor in 30.5% of all injury-related deaths. Older adolescents (aged 15-19 yr), older adults (aged 65 yr and older), and males across all age groups are most likely to sustain a TBI. The incidence of TBI, as measured by combined emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, has steadily risen. For example, from 2001 to 2005, the TBI rates increased from 521 to 616 per 100,000 population and, in 2010, increased to 824 per 100,000 population. In addition, deaths related to TBI decreased by 7% over the same 10-year period. [18, 19]

TBI is the leading cause of disability and death in children aged 0-4 yr and adolescents aged15-19 yr. Also, it is estimated that 145,000 children and adolescents (ages 0-19 yr) are living with lasting cognitive, physical, or behavioral effects of TBI. [18, 19]

Approximately 70-90% of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury (TBI) die before reaching the hospital, and 50% of those who survive to reach the hospital die during resuscitation attempts in the ED. Approximately 35,000 civilian deaths are attributed to penetrating brain injury each year, with firearms-related injuries being the leading cause of mortality in this group. Of the 333,169 US military TBIs recorded between 2000-2015, 4,904 were classified as penetrating TBI. [20]

Pathophysiology

The pathologic consequences of penetrating head wounds depend on the circumstances of the injury, including the properties of the weapon or missile, the energy of the impact, and the location and characteristics of the intracranial trajectory. [21] Following the primary injury or impact, secondary injuries may develop. Secondary injury mechanisms are defined as pathologic processes that occur after the time of the injury and adversely affect the ability of the brain to recover from the primary insult. A biochemical cascade begins when a mechanical force disrupts the normal cell integrity, producing the release of numerous enzymes, phospholipids, excitatory neurotransmitters (glutamate), and free oxygen radicals that propagate further cell damage.

Missile wounds

Missiles range from low-velocity bullets used in handguns, as shown in the image below, or shotguns to high-velocity metal-jacket bullets fired from military weapons. [22, 23] Low-velocity civilian missile wounds occur from air rifle projectiles, nail guns used in construction devices, stun guns used for animal slaughter, and shrapnel produced during explosions. Bullets can cause damage to brain parenchyma through 3 mechanisms: (1) laceration and crushing, (2) cavitation, and (3) shock waves. The injury may range from a depressed fracture of the skull resulting in a focal hemorrhage to devastating diffuse damage to the brain.

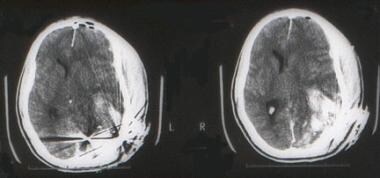

A 65-year-old man experienced a gunshot wound to the right frontoparietal region. A CT scan shows that the bullet crossed the midline, lacerated the superior longitudinal sinus, and produced a large midline subdural hematoma. The patient presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 4 and died.

A 65-year-old man experienced a gunshot wound to the right frontoparietal region. A CT scan shows that the bullet crossed the midline, lacerated the superior longitudinal sinus, and produced a large midline subdural hematoma. The patient presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 4 and died.

As stated previously, a wound in which the projectile breaches the cranium but does not exit is described technically as penetrating, and an injury in which the projectile passes entirely though the head, leaving both entrance and exit wounds, is described as perforating. This distinction has some prognostic implications. In a series of missile-related head injuries during the Iran-Iraq war, a poor postsurgical outcome occurred in 50% of patients treated for perforating wounds, as compared to only 20% of those with penetrating wounds. [24]

In missile wounds, the amount of damage to the brain depends on numerous factors, including (1) the kinetic energy imparted, (2) the trajectory of the missile and bone fragments through the brain, (3) intracranial pressure (ICP) changes at the moment of impact, and (4) secondary mechanisms of injury. The kinetic energy is calculated employing the formula 1/2mv2, where m is the bullet mass and v is the impact velocity.

At the time of impact, injury is related to (1) the direct crush injury produced by the missile, (2) the cavitation produced by the centrifugal effects of the missile on the parenchyma, and (3) the shock waves that cause a stretch injury. As a projectile passes through the head, tissue is destroyed and is either ejected out of the entrance or exit wounds or compressed into the walls of the missile tract. This creates both a permanent cavity that is 3-4 times larger than the missile diameter and a pulsating temporary cavity that expands outward. The temporary cavity can be as much as 30 times larger than the missile diameter and causes injury to structures a considerable distance from the actual missile tract.

Stab wounds

Stab wounds (see the image below) represent a smaller fraction of penetrating head injuries. The causes may be from knives, nails, spikes, forks, scissors, and other assorted objects. [7] Penetrations most commonly occur in the thin bones of the skull, especially in the orbital surfaces and the squamous portion of the temporal bone. The mechanisms of neuronal and vascular injury caused by cranial stab wounds may differ from those caused by other types of head trauma. Unlike missile injuries, no concentric zone of coagulative necrosis caused by dissipated energy is present. Unlike motor vehicle accidents, no diffuse shearing injury to the brain occurs.

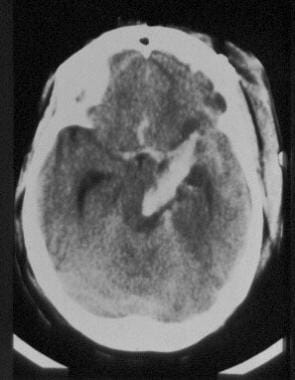

A CT scan of a young female who presented to the emergency department with a stab wound to the head produced by a large knife shows the extent of intracranial damage, which affects midline structures.

A CT scan of a young female who presented to the emergency department with a stab wound to the head produced by a large knife shows the extent of intracranial damage, which affects midline structures.

Unless an associated hematoma or infarct is present, cerebral damage caused by stabbing is largely restricted to the wound tract. A narrow elongated defect, or so-called slot fracture, sometimes is produced by a stab wound and is diagnostic when identified. However, in some cases in which skull penetration is proven, no radiologic abnormality can be identified. In a series of stab wounds, de Villiers reported a mortality of 17%, mostly related to vascular injury and massive intracerebral hematomas. [8]

Stab wounds to the temporal fossa are more likely to result in major neurologic deficits because of the thinness of the temporal squama and the shorter distance to the deep brain stem and vascular structures. Patients in whom the penetrating object is left in place have a significantly lower mortality than those in whom the objects are inserted and then removed (26% versus 11%, respectively). [8]

Skull perforations and fractures

The local variations in thickness and strength of the skull and the angle of the impact determine the severity of the fracture and injury to the brain (see the images below). Impacts striking the skull at nearly perpendicular angles may cause bone fragments to travel along the same trajectory as the penetrating object, to shatter the skull in an irregular pattern, or to produce linear fractures that radiate away from the entry defect. Grazing or tangential impacts produce complex single defects with both internal and external beveling of the skull, with varied degrees of brain damage.

Lateral skull x-ray film of a patient who presented with a severe intracranial injury produced by a golf club.

Lateral skull x-ray film of a patient who presented with a severe intracranial injury produced by a golf club.

Presentation

The clinical condition of the patient depends mainly on the mechanism (velocity, kinetic energy), anatomic location of the lesions, and associated injuries.

Traumatic intracranial hematomas

Traumatic intracranial hematomas can occur alone or in combination and constitute a common and treatable source of morbidity and mortality resulting from brain shift, brain swelling, cerebral ischemia, and elevated ICP. Patients present with the signs and symptoms of an expanding intracranial mass, and the clinical course varies according to the location and rate of accumulation of the hematoma. The classic clinical picture of epidural hematomas is described as involving a lucid interval following the injury; the patient is stunned by the blow, recovers consciousness, and lapses into unconsciousness as the clot expands.

Epidural hematomas

Most traumatic epidural hematomas become rapidly symptomatic, with progression to coma. Acute subdural hematoma occurs in association with high rates of acceleration and deceleration of the head that takes place at the time of trauma. This remains one of the most lethal of all head injuries because the impact causing acute subdural hematoma commonly results in associated severe parenchymal brain injuries. [25]

Intracerebral hematomas

Intracerebral hematomas result from direct rupture of small vessels within the parenchyma at the moment of impact. Patients typically present with a focal neurologic deficit related to the location of the hematoma or with signs of mass effect and increased ICP. The occurrence of delayed traumatic intracerebral hematomas is well documented in the literature.

Delayed intracerebral hematomas

The time interval for the development of delayed intracerebral hematomas ranges from hours to days. Although these lesions may develop in areas of previously demonstrated contusion, they frequently occur in the presence of completely normal results on the initial CT scan. Patients with this diagnosis typically meet the following criteria: (1) a definite history of trauma, (2) an asymptomatic interval, and (3) an apoplectic event with sudden clinical deterioration.

Contusions

Contusions consist of areas of perivascular hemorrhage about small blood vessels and necrotic brain. Typically, they assume a wedgelike shape, extending through the cortex to the white matter. When the pia-arachnoid layer is torn, the injury is termed a cerebral laceration. Clinically, cerebral contusions serve as niduses for delayed hemorrhage and brain swelling, which can cause clinical deterioration and secondary brain injury. [26]

Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage

Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage usually is a result of various forces that produce stress sufficient to damage superficial vascular structures running in the subarachnoid space. Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage may predispose to cerebral vasospasm and diminished cerebral blood flow, thereby increasing morbidity and mortality as a result of secondary ischemic damage.

Diffuse axonal injury or shearing injury

Diffuse axonal injury or shearing injury has become recognized as one of the most important forms of primary injury to the brain. In the most extreme form, patients present with immediate prolonged unconsciousness from the moment of injury and subsequently remain vegetative or severely impaired.

Glasgow Coma Scale

A critical factor in early treatment decisions and in long-term outcome after penetrating head injuries is the patient's initial level of consciousness. Although many methods of defining level of consciousness exist, the most widely used measure is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (see the table below).

Table. Glasgow Coma Scale (Open Table in a new window)

Points |

Eye Opening |

Best Verbal |

Best Motor |

6 |

… |

… |

Follows commands |

5 |

… |

Appropriate |

Localizes pain |

4 |

Spontaneous |

Inappropriate |

Withdraws to pain |

3 |

In response to voice |

Moaning |

Flexion (decorticate) |

2 |

In response to pain |

Incomprehensible |

Extension (decerebrate) |

1 |

None |

None |

None |

The level of consciousness can be lowered independent of head injury for numerous reasons, including shock, hypoxia, hypothermia, alcohol intoxication, postictal state, and administration of sedatives or narcotics. Therefore, a more reliable assessment of severity and, thus, a more meaningful predictor of outcome is provided by the postresuscitation GCS score (hereafter referred to as GCS), which generally refers to the best level obtained within the first 6-8 hours of injury following nonsurgical resuscitation. [11, 3, 15] This allows patients to be categorized into 3 levels, as follows:

-

Minor or mild injury includes those patients with an initial level of 13-15.

-

Moderate injury includes patients with a score of 9-12.

-

Severe injury refers to a postresuscitation level of 3-8 or a subsequent deterioration to 8 or less.

Patients with severe head injury typically fulfill the criteria for coma, have the highest incidence of intracranial mass lesions, and require intensive medical and, often, surgical intervention.

Lack of abnormal pupillary response to light and the visibility of basal cisterns may increase the need for urgent care. In those with injuries close to the Sylvian fissure and with a projectile fragment crossing 2 dural compartments, CT angiography and, if needed, digital subtraction angiography may be needed to rule out traumatic intracranial aneurysms. [3]

In a study of 786 patients with gunshot wounds to the head, 712 (91%) died. Admission GCS score, trajectory of the missile track, abnormal pupillary response (APR) to light, and patency of basal cisterns were significant determinants of patient outcome. Exclusion of GCS score from the regression models indicated missile trajectory and APR to light were significant in determining outcome. [27]

Relevant Anatomy

Penetrating objects to the cranium must traverse through the scalp, through the skull bones, and through the dura mater before reaching the brain.

The scalp consists of 5 different anatomic layers: the skin (S); the subcutaneous tissue (C); the galea aponeurotica (A), which is continuous with the musculoaponeurotic system of the frontalis, occipitalis, and superficial temporal fascia; underlying loose areolar tissue (L); and the skull periosteum (P).

The subcutaneous layer possesses a rich vascular supply that contains an abundant communication of vessels that can result in a significant blood loss when the scalp is lacerated. The relatively poor fixation of the galea to the underlying periosteum of the skull provides little resistance to shear injuries that can result in large scalp flaps or so-called scalping injuries. This layer also provides little resistance to hematomas or abscess formation, and extensive fluid collections related to the scalp tend to accumulate in the subgaleal plane.

The bones of the calvaria have 3 distinct layers in the adult—the hard internal and external tables and the cancellous middle layer, or diploe. Although the average thickness is approximately 5 mm, the thickest area is usually the occipital bone and the thinnest is the temporal bone. The calvaria is covered by periosteum on both the outer and inner surfaces. On the inner surface, it fuses with the dura to become the outer layer of the dura.

Aesthetically, the frontal bone is the most important because only a small portion of the frontal bone is covered by hair. In addition, it forms the roof and portions of the medial and lateral walls of the orbit. Displaced frontal fractures therefore may cause significant deformities, exophthalmus, or enophthalmos. The frontal bone also contains the frontal sinuses, which are paired cavities located between the inner and outer lamellae of the frontal bone. The lesser thickness of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus makes this area more susceptible to fracture than the adjacent tempora-orbital areas.

The dura mater or pachymeninx is the thickest and most superficial meninx. It consists of 2 layers—a superficial layer that fuses with the periosteum and a deeper layer. In the same region between both layers, large venous compartments or sinuses are present. A laceration through these structures can produce significant blood loss or can be responsible for producing epidural or subdural hematomas.

-

A young man arrived in the emergency department after experiencing a gunshot wound to the brain. The entrance was on the left occipital region. A CT scan shows the skull fracture and a large underlying cerebral contusion. The patient was taken to the operating room for debridement of the wound and skull fracture, with repair of the dura mater. He was discharged in good neurological condition, with a significant visual field defect.

-

Lateral skull radiograph of a young female who presented to the emergency department with a stab wound to the head produced by a large knife.

-

A CT scan of a young female who presented to the emergency department with a stab wound to the head produced by a large knife shows the extent of intracranial damage, which affects midline structures.

-

Lateral skull x-ray film of a patient who presented with a severe intracranial injury produced by a golf club.

-

The patient presented to the emergency department with a golf club in his head. The club was removed in the operating room.

-

A 65-year-old man experienced a gunshot wound to the right frontoparietal region. A CT scan shows that the bullet crossed the midline, lacerated the superior longitudinal sinus, and produced a large midline subdural hematoma. The patient presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 4 and died.

-

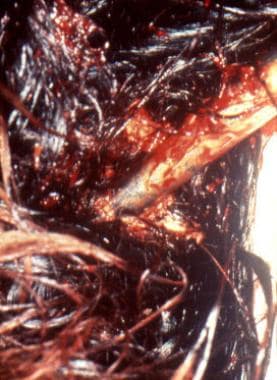

Intraoperative view of a middle-aged male with an open depressed skull fracture.

-

Intraoperative view the surgical reconstruction repair of a complex skull fracture.

-

A 57-year-old male who suffered a motorcycle accident. He was not wearing a helmet. He suffered a severe abrasion with tissue loss through skin, temporalis muscle, temporal bone, and dura. Note brain tissue exposed through his wound. He was taken urgently to surgery for debridement and reconstruction using a rotational flap.