Practice Essentials

Salivary gland tumors (SGTs) are uncommon and represent 2-3% of head and neck neoplasms. [1]

The salivary glands exist as larger named “major” glands and also as many widely dispersed “minor” glands that exist throughout the upper aerodigestive submucosa (ie, palate, lip, pharynx, nasopharynx, larynx, and parapharyngeal space). The paired major salivary glands include the following:

-

Parotid

-

Submandibular

-

Sublingual

Approximately 80% of SGTs originate in the parotid gland; the remaining SGTs arise in the submandibular, sublingual, and minor salivary glands. A good rule of thumb is that the likelihood of an SGT being malignant is inversely proportional to the size of the gland from which it originates. Specifically, the odds of malignancy in the parotid, submandibular, and minor salivary glands are 20%, 50%, and 80%, respectively.

The approach to a suspected SGT begins with a thorough history and a meticulous physical examination. SGTs usually manifest as an enlargement or growth of the affected gland. Depending on the location of the gland, they can present with nerve compression symptoms when patients are seen later in the course with larger tumors. Clinicians may investigate and exclude a history of weight loss, underlying infectious processes (eg, fever, elevated white blood cell [WBC] count, and concomitant lymphadenopathy), and clinical indications of lymphoma type B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, and chills).

Additionally, clinical workup should aim to exclude malignant neoplasms originating from the salivary tissue or malignancies that originate in the mucosal or cutaneous lining of the head and neck region but may exhibit contiguous or metastatic involvement of salivary tissue. Features such as pain, rapid growth, cranial neuropathies, fixation to soft tissue or bone, and associated adenopathy should alert the clinician to the possibility of a malignant diagnosis.

Diagnostic imaging (eg, ultrasonography [US], computed tomography [CT], and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) often provides useful information before definitive surgical therapy. Cytopathologic evaluation using fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or core needle biopsy (CNB) may be performed in selected cases and may help dictate the extent of surgical management. However, for most patients presenting with salivary masses, the decision to intervene surgically is largely based on clinical assessment and imaging findings. [2, 3, 4, 5]

From the infancy of surgical intervention, salivary gland surgery was limited to the treatment of ranulas and oral calculi, with the first recorded salivary surgery being a ranula excision performed by Guy de Chauliac of France in 1363. [6] The concept of surgical excision of a parotid tumor has been attributed to Bertrandi in 1802. The initial applications of this surgery included an extensive approach, causing serious disfiguration and disability.

By approximately 1850, the focus shifted toward dissection and the intimate relation between the facial nerve and the parotid gland. Attempts were made to perform the surgery with nerve preservation. John C Warren, MD, was the first to use ether inhalation anesthesia during his resection of a parotid tumor in Boston in 1846. In 1892, Codreanu (a Romanian native) performed the first total parotidectomy with facial nerve preservation. Grafting of the facial nerve after resection was attempted in the early 1950s.

In 1958, Beahrs and Adson eloquently described the relevant anatomy and surgical technique of current parotid gland surgery. [7] They stressed surgical landmarks for avoiding injury to the main trunk and branches of the facial nerve and advocated complete removal of the superficial portion of the parotid gland for noninvasive lesions confined to that portion of the gland.

For patient education resources, see the Cancer Center, as well as Cancer of the Mouth and Throat.

Anatomy

The parotid gland is situated in the musculoskeletal recess formed by portions of the temporal bone, atlas, and mandible, along with their related muscles. The gland is divided into superficial and deep lobes on the basis of the plane in which the extratemporal portion of the facial nerve runs. The deep lobe can extend in the parapharyngeal space via the stylomandibular tunnel. The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia surrounds the parotid gland. This fascia has an anteroinferior portion that becomes the stylomandibular ligament, separating the parotid gland from the submandibular gland.

The facial nerve exits the stylomastoid foramen just posterior to the base of the styloid, gives off small branches to the postauricular and posterior belly of the digastric muscles, and then turns anterolaterally. The main trunk then becomes embedded in parotid tissue and divides into temporofacial and cervicofacial branches just superficial to the retromandibular vein. Beyond this point, the nerve anatomy varies. In general, however, there are five peripheral nerve branches, as follows:

-

Temporal or frontal

-

Zygomatic

-

Buccal

-

Marginal mandibular

-

Cervical

Multiple landmarks are used to identify the main trunk of the facial nerve during surgery. (See the image below.)

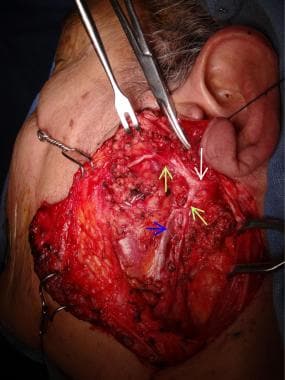

Facial nerve (white arrow) and its divisions (green arrows) are shown. Retromandibular vein is visible (blue arrow).

Facial nerve (white arrow) and its divisions (green arrows) are shown. Retromandibular vein is visible (blue arrow).

The submandibular gland encompasses most of the submandibular or digastric triangle. Like the parotid gland, the submandibular gland can be divided into superficial and deep lobes on the basis of the relationship with the mylohyoid muscle. The marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve courses between the deep surface of the platysma and the investing fascia that lies over the submandibular gland. The facial artery and vein are located just deep to this nerve, and ligation and superior traction of these vascular structures can prevent nerve injury during surgery.

Located along the posterior border of the mylohyoid are the lingual nerve, submandibular ganglion, and submandibular duct (Wharton duct). The hypoglossal nerve courses deep to the tendon of the digastric and thus lies medial to the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia.

The sublingual gland is located between the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles. The gland is rather superficial and is covered by only a thin layer of oral mucosa; thus, it can often be palpated in the floor of the mouth.

The minor salivary glands are widely dispersed throughout the upper respiratory tract, including the palate, lip, pharynx, nasopharynx, larynx, and parapharyngeal space. The greatest densities of glands are located in the hard (250 glands) and soft (150 glands) palates.

Pathophysiology

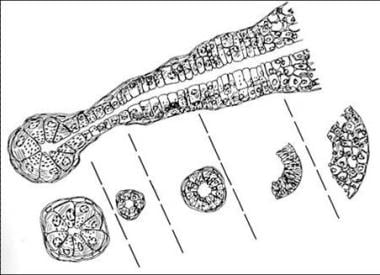

The histogenesis of SGTs is based on the salivary gland unit (see the image below). According to the multicellular theory of SGTs, pleomorphic adenomas originate from the intercalated duct cells and myoepithelial cells; oncocytic tumors originate from the striated duct cells; acinic cell tumors originate from the acinar cells; and mucoepidermoid and squamous cell tumors originate from the excretory duct cells.

Etiology

Although the etiology of SGTs is unknown, associations with environmental or genetic factors have been suggested. [8]

Smoking has been closely associated with Warthin tumors. Radiation exposure has been linked to the development of the benign Warthin tumor and to the malignant mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Epstein-Barr virus may be a factor in the development of lymphoepithelial tumors of the salivary glands. Genetic alterations (eg, allelic loss, monosomy and polysomy, and structural rearrangement) have been studied as factors in the development of SGTs, and many salivary neoplasms have been shown to possess tumor-specific genetic rearrangements. [1]

Epidemiology

SGTs represent 2-3% of head and neck neoplasms and are more common in women than in men. The peak incidence is in the third and fourth decades of life. Pleomorphic adenomas are the most common benign SGTs, followed by Warthin tumors (papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum; see the image below).

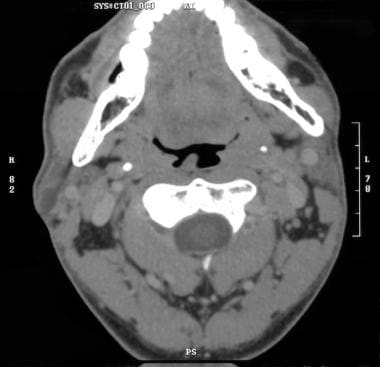

Heterogeneous, predominantly low-density mass in tail of right parotid gland with minimal thin peripheral enhancement consistent with Warthin tumor.

Heterogeneous, predominantly low-density mass in tail of right parotid gland with minimal thin peripheral enhancement consistent with Warthin tumor.

In addition to these two most common entities, the updated 2022 classification by the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized 13 additional types of benign epithelial tumors of the salivary glands, with the addition of the following [1, 8] :

-

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma

-

Keratocystoma

-

Intercalated duct adenoma

-

Striated duct adenoma

Prognosis

Whereas surgical excision of benign SGTs can have specific consequences or complications, given the unique anatomic locations of these lesions, the overall outcome after removal is excellent.

Pleomorphic adenomas, in particular, have a very low rate of recurrence, which is presumed to be the result of incomplete surgical excision due to pseudopod extension of the tumor. If untreated, benign pleomorphic adenoma may, in rare cases, undergo transition to a malignant variant called carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma; the rate of such transformation is estimated at 10% over 10-15 years.

-

Histology of salivary gland unit.

-

Coronal MRI demonstrating benign tumor of parapharyngeal space.

-

Right submandibular benign salivary gland tumor in 42-year-old woman.

-

Pictures before (above, left) and after (above, right) treatment for benign mandibular gland tumor. Specimen picture of gland (below).

-

Right parotid gland is slightly larger than left; normal variation.

-

Prominent bilateral parotid glands with homogenous parenchyma; normal variation.

-

Normal right submandibular sialogram.

-

Normal CT scan after right submandibular sialogram.

-

Normal CT scan after right submandibular sialogram.

-

In this patient with history of parotitis, note 7-mm lobulated calcification anteriorly within superficial right parotid gland with focally dilated ducts. Dystrophic calcifications due to remote inflammatory disease are also present bilaterally in tonsillar fossa.

-

Note 12-mm right parotid, smoothly marginated, multilobulated, solid lesion, without focal calcification or necrosis. This was proven to be pleomorphic adenoma.

-

Note 2- × 1.5-cm uniformly enhancing, smoothly marginated mass in superficial right parotid gland without necrosis or calcification, which is consistent with epithelial neoplasm such as pleomorphic adenoma.

-

Coronal image of patient with history of parotitis.

-

Heterogeneous, predominantly low-density mass in tail of right parotid gland with minimal thin peripheral enhancement consistent with Warthin tumor.

-

In this patient with infectious sialoadenitis, note inhomogeneous, enlarged left submandibular gland with mild thickening of adjacent platysma.

-

After radiation treatment of right parotid sialoadenitis.

-

After radiation treatment of right sialoadenitis.

-

Nodular and cystic changes in both parotid glands. These changes are stable in this patient with history of chronic sialoadenitis.

-

Dense, small, solid lesions in parotid glands (more on left side than on right) in patient with lymphoma. This is representative of lymphomatous involvement of glands.

-

Ill-defined masses in parotid glands bilaterally, proven to be large B-cell lymphoma in this patient with known Sjögren disease.

-

Large B-cell lymphoma in patient with known Sjögren disease.

-

Large B-cell lymphoma in patient with known Sjögren disease.

-

Bilateral, solid, inhomogeneous parotid gland masses that are larger on left side than on right, with minimal necrosis. These were caused by lymphoma.

-

Facial nerve (white arrow) and its divisions (green arrows) are shown. Retromandibular vein is visible (blue arrow).

-

Parotidectomy. Left parotid mass; preoperative marking of modified Blair incision on skin.

-

Parotidectomy. Wide plane maintaining thick vascularized skin flap is raised anteriorly. Note that greater auricular nerve is preserved, when possible, during this dissection.

-

Parotidectomy. With wide plane of dissection maintained, sternocleidomastoid muscle and posterior belly of digastric muscle are exposed. Main trunk of facial nerve is starting to appear (white arrow).

-

Facial nerves. Note network between zygomatic branch and buccal branch.

-

Facial nerve branches.

-

Exposed facial nerve branches after superficial parotidectomy.

-

Facial nerves. Note variations in nerve sizes and change of takeoff locations of branches.

-

Facial nerves. Note two main trunks, frontozygomatic and cervical-marginal-mandibular.