Practice Essentials

Insulinomas are the most common cause of hypoglycemia resulting from endogenous hyperinsulinism. Approximately 90-95% of insulinomas are benign, and long-term cure with total resolution of preoperative symptoms is expected after complete resection. [1, 2] See the image below.

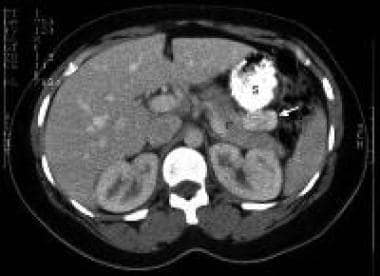

CT scan image with oral and intravenous contrast in a patient with biochemical evidence of insulinoma. The 3-cm contrast-enhancing neoplasm (arrow) is seen in the tail of the pancreas (P) posterior to the stomach (S) (Yeo, 1993).

CT scan image with oral and intravenous contrast in a patient with biochemical evidence of insulinoma. The 3-cm contrast-enhancing neoplasm (arrow) is seen in the tail of the pancreas (P) posterior to the stomach (S) (Yeo, 1993).

Signs and symptoms

Insulinomas are characterized clinically by the Whipple triad, as follows:

-

Presence of symptoms of hypoglycemia (about 85% of patients)

-

Documented low blood sugar at the time of symptoms

-

Reversal of symptoms by glucose administration

About 85% of patients with insulinoma present with one of the following symptoms of hypoglycemia:

-

Diplopia

-

Blurred vision

-

Palpitations

-

Weakness

Hypoglycemia can also result in the following:

-

Confusion

-

Abnormal behavior

-

Unconsciousness

-

Amnesia

-

Adrenergic symptoms (from hypoglycemia-related catecholamine release): Weakness, sweating, tachycardia, palpitations, and hunger

-

Seizures

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Lab studies

Failure of endogenous insulin secretion to be suppressed by hypoglycemia is the hallmark of an insulinoma. Thus, the finding of inappropriately elevated levels of insulin in the face of hypoglycemia is the key to diagnosis.

The biochemical diagnosis of insulinoma is established in 95% of patients during prolonged fasting (up to 72 h) when the following results are found:

-

Serum insulin levels of 10 µU/mL or more (normal < 6 µU/mL)

-

Glucose levels of less than 40 mg/dL

-

C-peptide levels exceeding 2.5 ng/mL (normal < 2 ng/mL)

-

Proinsulin levels greater than 25% (or up to 90%) of immunoreactive insulin levels

-

Screening for sulfonylurea negative

Approximately 5% of patients with insulinomas will show postprandial but not fasting hypoglycemia, and in those cases the diagnosis can be established by laboratory testing performed after the patient consumes a standardized meal. [3]

Imaging studies

Insulinomas can be located with the following imaging modalities:

-

Real-time transabdominal high-resolution ultrasonography: 50% sensitivity

-

Intraoperative transabdominal high-resolution ultrasonography with the transducer being passed over the exposed pancreatic surface: Detects more than 90% of insulinomas

-

CT scanning: 82-94% sensitivity

-

MRI [7]

-

Arteriography: Previously the standard for insulinoma localization but highly operator dependent, with reported sensitivities ranging from 29–64%

-

Selective arterial calcium stimulation testing: Since calcium stimulates insulin secretion by insulinomas, selective injection of calcium into small arterial branches of the celiac system with measurement of hepatic vein insulin during each injection can localize tumors; most studies report ≥90% accuracy. [8]

-

PET/CT with gallium-68 DOTA-(Tyr3)-octreotate (Ga-DOTATATE): 90% sensitivity; possible adjunct study when other imaging studies are negative and minimally invasive surgery is planned [9]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Pharmacologic therapy

Pharmacologic treatment is designed to prevent hypoglycemia and, in patients with malignant tumors, to reduce the tumor burden. Agents used in this therapy include the following:

-

Diazoxide: Reduces insulin secretion

-

Hydrochlorothiazide: Counteracts edema and hyperkalemia secondary to diazoxide and potentiates its hyperglycemic effect

-

Somatostatin analogs (octreotide, lanreotide): Prevent hypoglycemia

-

Peptide receptor radioligand therapy: Lutetium Lu 177 dotatate (Lutathera); binds with and kills insulinoma cells

-

Everolimus: For patients with metastatic insulinoma and refractory hypoglycemia

-

Combination chemotherapy: For patients with metastatic insulinoma and refractory hypoglycemia

Surgery:

-

Laparoscopic surgery: A large study from Spain showed laparoscopic surgery to be safe and effective in benign and malignant tumor resection [10]

-

Enucleation: Because insulinomas are usually benign, they may be removed by enucleation

-

If enucleation is not possible, a larger pancreatic resection, including pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy, may be necessary

-

Subtotal pancreatectomy with enucleation: With insulinomas associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), subtotal pancreatectomy with enucleation of tumors from the pancreatic head and uncinate process often is necessary because of frequent multiple tumors in MEN1. [11]

-

Even when metastases are found, surgical excision is usually preferred before any medical, chemotherapeutic, or other interventional therapy is considered. The goal of surgery is to resect all gross disease. This may include performing wedge resections or ablations of hepatic metastases.

Ablation:

-

Endoscopic ultrasound–guided radiofrequency or ethanol ablation has proved effective for small localized insulinomas, especially in patients considered unfit for surgery. [3]

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Insulinomas are the most common cause of hypoglycemia resulting from endogenous hyperinsulinism. In a large single-center series of 125 patients with neuroendocrine tumors, insulinomas constituted the majority of cases (55%), followed by gastrinomas (36%), VIPomas (vasoactive intestinal polypeptide tumor) (5%), and glucagonomas (3%). [12]

In 1927, Wilder established the association between hyperinsulinism and a functional islet cell tumor. [13] In 1929, Graham achieved the first surgical cure of an islet cell adenoma. Insulinomas can be difficult to diagnose. It was not uncommon for patients to have been misdiagnosed with psychiatric illnesses or seizure disorders before insulinoma was recognized.

Pathophysiology

An insulinoma is a neuroendocrine tumor, deriving mainly from pancreatic islet cells, that secretes insulin. Some insulinomas also secrete other hormones, such as gastrin, 5-hydroxyindolic acid, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), glucagon, human chorionic gonadotropin, and somatostatin. The tumor may secrete insulin in short bursts, causing wide fluctuations in blood levels.

About 90% of insulinomas are benign. Approximately 10% of insulinomas are malignant (metastases are present). Approximately 10% of patients have multiple insulinomas; of patients with multiple insulinomas, 50% have multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). Overall, insulinomas are associated with MEN1 in 5% of patients. On the other hand, 21% of patients with MEN1 develop insulinomas. Because of the association of insulinomas with MEN1, consideration should be given to screening family members of insulinoma patients for MEN1. [14]

An in vitro study by Henquin et al identified three distinct patterns of insulin secretion by insulinomas, as follows [15] :

-

Group A – Qualitatively normal responses to absence or excess levels of glucose, leucine, diazoxide, tolbutamide, and extracellular calcium chloride (CaCl 2); concentration-dependent effect of glucose, but excessive insulin secretion in both low- and high-glucose conditions

-

Group B – Large insulin responses to 1 mmol/L glucose, resulting in very high basal secretion rates inhibited by diazoxide and restored by tolbutamide but not further augmented by other agents, except for high levels of CaCl

-

Group C – Very low rates of insulin secretion and virtually no response to stimuli (including high CaCl 2 concentration) and inhibitors (with CaCl 2 omission paradoxically stimulatory).

Increased expression of the phosphorylated mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway and its downstream serine/threonine kinase p70S6k has been observed in insulinoma tumor specimens. [16] This discovery led to studies that established the mTOR inhibitor everolimus as a therapeutic option in insulinoma. [17]

Etiology

The genetic changes in neuroendocrine tumors are under investigation. [18] The gene of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, an autosomal dominant disease, is called MEN1 and maps to band 11q13. MEN1 is thought to function as a tumor suppressor gene. Data suggest that the MEN1 gene also is involved in the pathogenesis of at least one third of sporadic neuroendocrine tumors. Researchers were able to detect loss of heterozygosity in band 11q13 in DNA samples from resected insulinoma tissue by using fluorescent microsatellite analysis.

In a study of 12 children with insulinoma, four cases showed heterozygous mutations of MEN1 on 11q. Aneuploidy of chromosome 11 and other chromosomes was common in both MEN1 and non-MEN1 insulinomas. [19]

One study showed k-ras mutation to be present in 23% of insulinomas. [18] Another study found T372R mutations in the YY1 gene in 30% of sporadic insulinomas. [20]

Most metastatic insulinomas appear to derive from non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. However, a few metastatic insulinomas may derive from non-metastatic insulinomas. [21]

Epidemiology

United States

Insulinomas are the most common functional pancreatic endocrine tumors, comprising 55% of such cases. The incidence is 1-32 cases per million persons per year. [22]

International

One source from Northern Ireland reported an annual incidence of 1 case per million persons. A study from Iran found 68 cases in a time span of 20 years in a university in Tehran. [23] A 10-year single-institution study from Spain of 49 consecutive patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery for neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors included 23 cases of insulinoma. [10] These reports may be an underestimate.

Mortality/Morbidity

Pancreatic fistula is the most common major complication of surgery for insulinoma, [24] Other surgical complications include pseudocyst, intra-abdominal abscess, pancreatitis, hemorrhage, and diabetes. In one systematic review of 6222 cases, the overall surgical mortality for insulinoma was 3.7%, primarily in patients with malignant, metastatic disease undergoing open surgery. Mortality was not seen in patients undergoing laparoscopic resection. [25] The median survival in patients with metastatic disease to the liver ranges from 16-26 months.

Race-, Sex-, and Age-related Demographics

Insulinomas have been reported in persons of all races. No racial predilection appears to exist.

Overall, the male-to-female ratio for insulinomas is 2:3 and the median age at diagnosis is about 47 years. [11] In insulinoma patients with MEN1, however, more cases are reported in men than in women, and the median age at diagnosis is younger, at 38 years. [11, 26]

Prognosis

Approximately 90-95% of insulinomas are benign. Long-term cure with complete resolution of preoperative symptoms is expected after complete resection.

Recurrence of benign insulinomas was observed in 5.4% of patients in a series of 120 patients over a period of 4-17 years. The same diagnostic and therapeutic approach was recommended, including surgical exploration and tumor resection. [27]

Patients may develop nonfunctioning metastatic disease to the liver up to 14 years after insulinoma resection. [28] Note that some insulinomas are indolent (depending on the tumor biology), resulting in prolonged survival.

-

CT scan image with oral and intravenous contrast in a patient with biochemical evidence of insulinoma. The 3-cm contrast-enhancing neoplasm (arrow) is seen in the tail of the pancreas (P) posterior to the stomach (S) (Yeo, 1993).

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography in a patient with an insulinoma. The hypoechoic neoplasm (arrows) is seen in the body of the pancreas anterior to the splenic vein (SV) (Rosch, 1992).