Practice Essentials

Menorrhagia (heavy vaginal bleeding or heavy uterine bleeding) is defined as menstruation at regular cycle intervals but with excessive flow (greater than 80 cc of blood loss per cycle or requiring more frequent than 2 hour changes of hygiene products) and/or duration (longer than 7 days), or perceived as heavy bleeding by the patient. It is one of the most common gynecologic complaints in contemporary gynecology. As the most common cause of irregular bleeding in women of reproductive age is pregnancy, this diagnosis should be excluded before any further testing or drug therapy.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms related by a patient with menorrhagia often can be more revealing than laboratory tests. A detailed patient history is imperative and should include inquiries about the following:

-

A detailed menstrual history (eg, last menstrual period, number of days of bleeding, the severity of bleeding, the presence of intermenstrual bleeding, time between menses)

-

Presence of pelvic pain related to menstrual cycle or bleeding pattern

-

Menses pattern from menarche including change in symptoms over time

-

Contraceptive use

-

Presence of hirsutism

-

Systemic illnesses (eg, hepatic, renal failure, and diabetes)

-

Symptoms of thyroid dysfunction

-

Excessive bruising or known bleeding disorders

-

Current medications (eg, hormones and anticoagulants)

-

Previous diagnoses or surgical procedures

The physical examination should be tailored to the differential diagnoses suggested by the history (Table 1). Initial inspection should include evaluation for the following:

Table 1. Differential diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding and associated clinical features. (Open Table in a new window)

Associated clinical features |

Common etiology |

Hirsutism, acne, obesity |

Polycystic ovary syndrome |

Ecchymosis, purpura, bleeding gums |

Bleeding disorder |

Galactorrhea, visual field defects |

Hyperprolactinemia |

Weight gain or loss, enlarged thyroid |

Thyroid disease |

Enlarged liver or spleen |

Hepatic dysfunction |

Enlarged uterus or discrete uterine masses |

Uterine leiomyoma, endometrial cancer |

Enlarged, boggy uterus |

Adenomyosis |

According to an international expert panel, an underlying coagulopathy or bleeding disorder should be considered when a patient has any of the following [1] :

-

Menorrhagia since menarche

-

Family history of bleeding disorders

-

Personal history of 1 or more of the following: (1) Notable bruising without known injury, (2) bleeding of the oral cavity or gastrointestinal tract without an obvious lesion, or (3) epistaxis of more than 10 minutes’ duration (possibly necessitating packing or cautery)

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies that may be useful include the following:

-

Complete blood cell count

-

Iron studies (eg, total iron-binding capacity [TIBC] and total iron)

-

Thyroid function tests and prolactin level

-

Liver function tests (LFTs) and renal function tests (eg, blood urea nitrogen [BUN] and creatinine)

-

Hormone assays (eg, luteinizing hormone [LH], follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], and androgen) for suspected polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS); adrenal function tests for suspected adrenal tumors

-

Coagulation factor studies (expensive and to be used sparingly)

Imaging studies and other diagnostic measures that may be helpful include the following:

-

Pelvic ultrasonography

-

Sonohysterography (saline-infusion sonography)

-

Cervical specimens (eg, Pap smear, sexually transmitted infection [STI] testing)

-

Endometrial biopsy (EMB)

-

Hysteroscopy

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Medical therapy should be tailored to treat the underlying cause of abnormal bleeding, characteristics of the patient (eg, age, coexisting medical diseases, family history, and desire for fertility). Agents used to alleviate heavy uterine bleeding unrelated to underlying systemic disease include the following:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Continuous dosing beginning on the first day of bleeding for 3-4 days or until bleeding ceases.

-

Combined hormonal contraceptives: Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) are a popular first-line therapy for women who desire contraception in addition to management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Dienogest−estradiol valerate has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for heavy menstrual bleeding; however, other pills on the market have also proven effective to control heavy menstruation. The estrogen-containing transvaginal ring or transdermal patch can also be used.

-

Progesterone-only containing contraceptives: Progestin is one of the most frequently prescribed medicines for menorrhagia. Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate injection can also be used. Rarely, an etonogestrel implant may be used.

-

Levonorgestrel intrauterine device: Approved by the FDA for treatment of menorrhagia in women who use intrauterine contraception.

-

Tranexamic acid

Clinically less commonly used agents may also include:

-

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists

-

Danazol

-

Conjugated estrogens

Surgical management has been the standard of treatment in menorrhagia when the cause is structural, when medical therapy fails to alleviate symptoms, or for ablation, uterine artery embolization, and hysterectomy, if the patient strongly desires definitive management and no longer desires childbearing. Options for surgical intervention include the following:

Nondefinitive therapy

-

Dilation and curettage: Used for diagnosis (and in the case of acute, life-threatening bleeding used for treatment) typically in combination with hysteroscopy.

-

Myomectomy

Definitive therapy

-

Uterine artery embolization

-

Hysterectomy

See Treatment for more detail.

Background

A normal menstrual cycle is 21-35 days in duration, with bleeding lasting an average of 7 days and flow measuring 25-80 mL. [9]

Menorrhagia (more contemporarily addressed as heavy menstrual bleeding) is defined as menstruation at regular cycle intervals but with excessive flow and/or duration and is one of the most common gynecologic complaints in contemporary gynecology. Clinically, menorrhagia is defined as total blood loss exceeding 80 mL per cycle, [10] menses lasting longer than 7 days, or bleeding that is considered bothersome in quantity to the patient. [11] The World Health Organization reports that 18 million women aged 30-55 years perceive their menstrual bleeding to be excessive. [12] Reports show that only 10% of these women experience blood loss severe enough to cause anemia or be clinically defined as menorrhagia; however, in cases where menstrual bleeding is bothersome, treatment is warranted. [11, 13, 14] In practice, measuring menstrual blood loss is difficult. Thus, the diagnosis is usually based upon the patient's history.

Table 2. Terminology for normal and abnormal menses. [15] (Open Table in a new window)

Quality |

Normal |

Abnormal |

Prior Terms |

Volume |

5-80 mL |

Light (< 5 mL) Heavy (>80 mL) |

Hypomenorrhea |

Duration |

≤8 days |

Prolonged (>8 days) |

|

Frequency |

21-35 days |

Frequent (< 21 days) Infrequent (>35 days) Amenorrhea (>90 days) |

Polymenorrhea Oligomenorrhea |

Regularity |

≤7 days |

Irregular (≥10 days) |

Menorrhagia must be distinguished clinically from other common gynecologic diagnoses. Many terms for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) are poorly defined and have largely been replaced by instead using descriptive terms (eg, menstrual volume, duration, frequency, and regularity) (Table 2). Polymenorrhea is bleeding that occurs more frequently than every 21 days, and oligomenorrhea is bleeding that occurs less frequently than every 35 days. Metrorrhagia (more contemporarily addressed as intermenstrual bleeding) is bleeding between menses. [16] AUB is often paired with descriptive terms to characterize bleeding patterns, then further characterized by etiology. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding has often been used interchangeably with AUB when no known etiology is identified, though this terminology is falling out of favor.

Nearly 30% of all hysterectomies performed in the United States are performed to alleviate heavy menstrual bleeding. [17] Historically, definitive surgical correction has been the mainstay of treatment for menorrhagia. Modern gynecology has trended toward conservative therapy to decrease risk to patients, control of costs, and the desire of many women to preserve their uterus.

Heavy menstrual bleeding is a subjective finding, making the exact problem definition difficult. Treatment success is usually evaluated subjectively by each patient, making positive outcome measurement difficult.

Pathophysiology

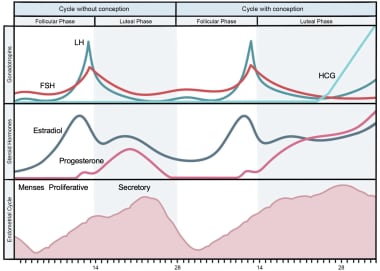

Knowledge of normal menstrual function is imperative in understanding the etiologies of menorrhagia. Four phases constitute the menstrual cycle: follicular, luteal, implantation (in the case of pregnancy), and menstrual (in the case of unfertilized ovum and no pregnancy) (Figure 1). [15]

In response to pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland synthesizes follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which induce the ovaries to produce estrogen and progesterone.

During the follicular phase, estrogen stimulation results in hypertrophy of endometrial tissue causing an increase in endometrial thickness in preparation for implantation. This also is known as the proliferative phase.

The luteal phase is intricately involved in the process of ovulation. During this phase, also known as the secretory phase, progesterone causes endometrial maturation. An LH surge is the harbinger of ovulation and release of an ovum from the ovary.

If fertilization occurs, beta-HCG will stimulate the corpus luteum to continue to make progesterone and ultimately maintain the implantation phase and continued decidualization of the endometrium. Without fertilization, estrogen and progesterone withdrawal results in menstruation.

The endometrium consists of two discrete zones, the basalis layer and the functionalis layer. The basalis layer allows for regeneration of the functionalis layer following menses and is positioned between the myometrium and functionalis layer. The functionalis layer is the most superficial layer, covering the entire uterine cavity and sloughs off with menstruation. Blood supply to the uterus is primarily through the uterine and ovarian arteries. These arteries anastomose and branch into arcuate arteries that supply the myometrium, which branch further into radial arteries to supply the two layers of the endometrium. The fall in progesterone at the end of the menstrual cycle leads to enzymatic breakdown of the functionalis layer, ultimately leading to sloughing of the endometrium and blood loss, also known as the menstrual phase.

Hemostasis relies on sufficient vasoconstriction and a functioning coagulation system, and a disruption in either element can affect menstruation. [15] Hemostasis of the endometrium is directly related to the functions of platelets and fibrin. Deficiencies in either of these components results in menorrhagia for patients with von Willebrand disease or thrombocytopenia. [18] Thrombi are seen in the functional layers but are limited to the shedding surface of the tissue. These thrombi are known as "plugs" because blood can only partially flow past them. Fibrinolysis limits the fibrin deposits in the unshed layer. Following thrombin plug formation, vasoconstriction occurs and contributes to hemostasis.

Many cases of AUB are secondary to anovulation. Without ovulation, the corpus luteum fails to form, resulting in no progesterone secretion. Unopposed estrogen allows the endometrium to proliferate and thicken. The endometrium finally outgrows its blood supply and degenerates. The result is asynchronous breakdown of the endometrial lining at different levels. This also is why anovulatory bleeding is heavier than normal menstrual flow. Unlike menorrhagia, anovulatory cycles are often described as irregular in timing as well as flow volume. [19]

Anatomic defects or growths (most typically polyps or fibroids but also malignancy) within the uterus can alter either of the aforementioned pathways (endocrinologic/hemostatic), causing significant uterine bleeding. The clinical presentation is dependent on the location and size of the gynecologic lesion.

Organic diseases also contribute to menorrhagia in the female patient. For example, in patients with renal failure, gonadal resistance to hormones, and hypothalamic-pituitary axis disturbances result in menstrual irregularities. Most women in this renal state are amenorrheic, but others also develop menorrhagia. If uremic coagulopathy ensues, it usually is due to platelet dysfunction and abnormal factor VIII function.

Due to the overwhelming factors that can contribute to the dysfunction of either the endocrine or hematologic pathways, in-depth knowledge of an existing organic disease is just as imperative as understanding the menstrual cycle itself.

Etiology

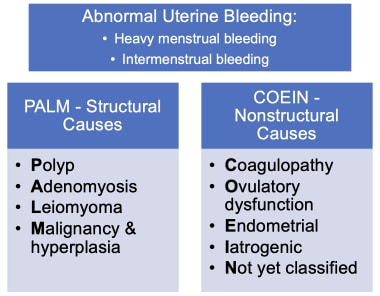

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has created a classification system for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) by bleeding pattern as well as bleeding etiology by using the acronym PALM-COEIN (Figure 2). AUB can be paired with descriptive terms to denote bleeding pattern, such as intermenstrual bleeding and heavy menstrual bleeding. The letters are sorted by structural and non-structural causes. The structural categories include polyp, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy, and hyperplasia, while the non-structural categories include coagulopathy, ovulatory disorders, endometrial disorders, iatrogenic, and those not otherwise classified. [20, 21]

PALM-COEIN classification system, approved by FIGO, for the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding and associated bleeding patterns (“heavy menstrual bleeding” and “intermenstrual bleeding”).

PALM-COEIN classification system, approved by FIGO, for the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding and associated bleeding patterns (“heavy menstrual bleeding” and “intermenstrual bleeding”).

Structural causes

Structural causes of menorrhagia include polyps, leiomyomas, adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia, and malignancy. Note the following:

-

Leiomyomas, commonly known as "fibroids" are benign smooth muscle neoplasms. Fibroids can be cervical or uterine in origin. Both fibroids and polyps can distort the uterine wall and/or endometrium. The FIGO system classified fibroids by location, including submucosal, intramural, subserosal or other (eg, cervical). [22]

-

The mechanism by which endometrial polyps or fibroids cause menorrhagia is not well understood. The blood supply to the fibroid or polyp is different compared to the surrounding endometrium and is thought to function independently. This blood supply is greater than the endometrial supply and may have impeded venous return, causing pooling in the areas of the fibroid. Heavy pooling is thought to weaken the endometrium in that area, and break-through bleeding ensues. Fibroids located within the uterine wall may inhibit muscle contracture, thereby preventing normal uterine attempts at hemostasis. This also is why intramural fibroids may cause a significant amount of pain and cramping.

-

Adenomyosis is characterized by endometrium located within the myometrium, often leading to uterine enlargement, menorrhagia, and dysmenorrhea.

-

Endometrial hyperplasia usually results from unopposed estrogen production leading to a proliferative endometrium but is biologically distinct from precancerous lesions of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) or atypical endometrial hyperplasia. [23] Endometrial hyperplasia can lead to endometrial cancer in 1-2% of patients with anovulatory bleeding, but it is a diagnosis of exclusion in postmenopausal bleeding (average age at menopause is 51). If a woman takes unopposed estrogen (without progesterone), their relative risk of endometrial cancer is 2.8 compared to nonusers. [16]

-

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States and typically presents in the postmenopausal period with irregular and continuous heavy uterine bleeding. Any patient older than age 45 years with changes in menstrual pattern or age 35 years and BMI greater than 30 should have endometrial sampling.

Nonstructural causes

Nonstructural causes of menorrhagia include coagulopathies, ovulatory disorders, endometrial disorders, iatrogenic, and those not otherwise classified. Consider the following:

-

Coagulation disorders can evade diagnosis until menarche when heavy menstrual bleeding presents as an unrelenting disorder. These include von Willebrand disease; factor II, V, VII, and IX deficiencies; prothrombin deficiency; idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP); and thrombasthenia. [1] See more on bleeding disorders below.

-

A common etiology of heavy uterine bleeding is anovulation, which includes varied underlying causes. Anovulation classically presents with menorrhagia at irregular intervals, often several months, without any known etiology. This is most common in adolescent and perimenopausal populations. [24, 25] Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of chronic anovulation. [15] The hallmarks of PCOS are anovulation, irregular menses, obesity, and hirsutism. Insulin resistance is common and increases androgen production by the ovaries.

-

Organ dysfunction causing menorrhagia includes hepatic or renal dysfunction. Liver dysfunction can impair production of clotting factors and reduces hormone metabolism (eg, estrogen), ultimately disrupting the HPO axis and leading to a proliferative endometrium. Either of these problems may lead to heavy uterine bleeding, which may worsen preexisting chronic anemia associated with chronic organ dysfunction.

-

Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism can result in menorrhagia. Even subclinical cases of hypothyroidism produce heavy uterine bleeding in 20% of patients. Menorrhagia usually resolves with correction of the thyroid disorder. [26]

-

Hyperprolactinemia can disrupt GnRH secretion leading to decreased LH and FSH levels, which ultimately cause hypogonadism. Bleeding patterns typically include amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea, though can range to include menorrhagia.

Iatrogenic causes of menorrhagia include intrauterine devices (IUDs), steroid hormones, chemotherapy agents, and medications (eg, anticoagulants). Consider the following:

-

Copper IUDs can cause increased menstrual bleeding and cramping due to local inflammatory effects (heavy vaginal bleeding is rarely noted with hormonal IUDs, although patients may report an unpredictable light bleeding pattern).

-

Steroid hormones such as prednisone can disrupt the normal menstrual cycle, which is typically restored upon cessation of the products.

-

Chemotherapy can affect gonadal cells, impacting hormone production and the menstrual cycle. It is variable whether normal ovarian function returns following completion of chemotherapy depending on the agent, duration, and other patient characteristics.

-

Anticoagulants decrease clotting factors needed to cease normal blood flow, including menses. This type of menorrhagia also is easily reversible; however, many patients require anticoagulation for other medical issues.

Bleeding disorders

An international expert panel including obstetrician/gynecologists and hematologists has issued guidelines to assist physicians in better recognizing bleeding disorders, such as von Willebrand disease, as a cause of menorrhagia and postpartum hemorrhage and to provide disease-specific therapy for the bleeding disorder. [1] Historically, a lack of awareness of underlying bleeding disorders has led to underdiagnosis in women with abnormal reproductive tract bleeding.

The panel provided expert consensus recommendations on how to identify, confirm, and manage a bleeding disorder. An underlying bleeding disorder should be considered when a patient has any of the following:

-

Menorrhagia since menarche

-

Family history of bleeding disorders

-

Personal history of 1 or more of the following: (1) Notable bruising without known injury; (2) bleeding of oral cavity or gastrointestinal tract without obvious lesion; and/or (3) epistaxis greater than 10 minutes duration (possibly necessitating packing or cautery)

If a bleeding disorder is suspected, consultation with a hematologist is suggested.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Although menorrhagia remains a leading reason for gynecologic office visits, only 10-20% of all menstruating women experience blood loss severe enough to be defined clinically as menorrhagia. [14] Abnormal uterine bleeding, including menorrhagia, is one of the leading causes of outpatient gynecologic visits.

Age-related demographics

Any woman of reproductive age who is menstruating may develop menorrhagia. Most patients with menorrhagia are older than 30 years. [9] The most common cause of heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents is persistent anovulation, though other common etiologies include coagulopathies and pregnancy. After adolescence, menorrhagia most frequently results from structural lesions, like leiomyomas, polyps, in addition to anovulatory cycles and endometrial hyperplasia. [24]

Prognosis

With proper workup, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care, prognosis is favorable, though largely depends on the etiology. Menorrhagia can significantly impact a person’s quality of life, ability to perform daily activities, productivity, and relationships.

Morbidity/mortality

Infrequent episodes of menorrhagia usually do not carry severe risks to women's general health.

Patients who lose more than 80 mL of blood, especially repetitively, are at risk for serious medical sequelae. These women are likely to develop iron-deficiency anemia because of their blood loss. Menorrhagia is the most common cause of anemia in premenopausal women. This usually can be remedied by oral ingestion of ferrous sulfate to replace iron stores as well as management of the abnormal bleeding. If the bleeding is severe enough to cause volume depletion, patients may experience shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, and other related symptoms. In the most serious of scenarios, anemia can lead to congestive heart failure and death. This level of anemia necessitates hospitalization for intravenous fluids, possible transfusion and prompt medical and/or surgical management.

Other sequelae associated with menorrhagia usually are related to the etiology. For example, with hypothyroidism, patients may experience symptoms associated with a low-functioning thyroid (eg, cold intolerance, hair loss, dry skin, weight gain) in addition to the effects of significant blood loss. [26]

Complications

Complications of heavy menstrual bleeding depend on the underlying etiology, but can include anemia, infertility, endometrial cancer, and associated complications of medical and/or surgical management. When severe, bleeding can lead to hypotension and even shock if not promptly evaluated and treated. [15]

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

As previously mentioned, patients with menorrhagia can experience a worse quality of life, including physical, mental, emotional, and social health, compared with those who have normal menstrual bleeding. People with heavy menstrual bleeding have decreased involvement in personal relationships, social activities, and work attendance. [27]

Menorrhagia and the many conditions that affect menstrual bleeding vary by race, ethnicity, and numerous other socioeconomic characteristics. Patients presenting for their first outpatient gynecology visit who live in more socioeconomically deprived areas report more severe heavy menstrual bleeding symptoms and a poorer quality of life. [27] Racial disparities with respect to menstrual bleeding are deeply rooted in assumptions of biological or genetic plausibility, without sound evidence and have historically been neglected. Black people experience higher rates of heavy menstrual bleeding compared with non-Hispanic White women. Some attribute differences in symptoms to the increased prevalence of uterine fibroids among Black people, though bias exists at every step of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. [28] For example, Black women and those aged 40 years or older were less likely to have documentation of nonsurgical treatment and less likely to receive a laparoscopic hysterectomy compared to other modes of hysterectomy. [29]

Period poverty is another example of an area where significant disparities exist. Period poverty is the injustice and inequity that people experience due to menstruation, which often results from insufficient access to menstrual supplies and information. [30] Period poverty most heavily impacts Black and Latina people compared with their counterparts. [30]

Endometrial cancer can cause menorrhagia and is one of many etiologies where significant racial disparities exist. Black people with endometrial cancer present at higher stage of disease, with more aggressive histology, have higher mortality rates than any other race or ethnicity, and are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care. [31] Further investigation and effort are needed to better address these disparities.

-

Phases of the menstrual cycle.

-

PALM-COEIN classification system, approved by FIGO, for the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding and associated bleeding patterns (“heavy menstrual bleeding” and “intermenstrual bleeding”).