Practice Essentials

Hodgkin lymphoma is a potentially curable lymphoma. [1] The World Health Organization classifies Hodgkin lymphoma into the following types [1, 2] :

-

Nodular sclerosing

-

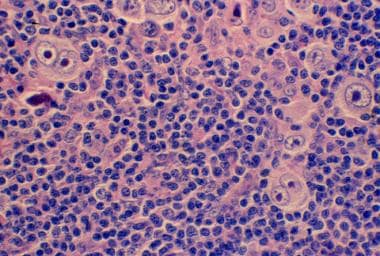

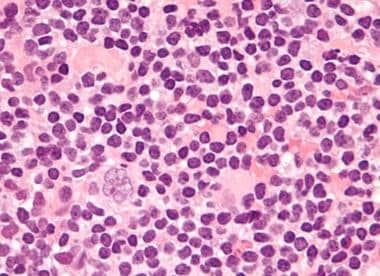

Mixed cellularity (see the image below)

-

Lymphocyte depleted

-

Lymphocyte rich

-

Nodular lymphocyte predominant

Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma showing both mononucleate and binucleate Reed-Sternberg cells in a background of inflammatory cells (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x200).

Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma showing both mononucleate and binucleate Reed-Sternberg cells in a background of inflammatory cells (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x200).

Signs and symptoms

Features of Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

-

Asymptomatic lymphadenopathy

-

Unexplained weight loss, unexplained fever, night sweats

-

Chest pain, cough, shortness of breath

-

Pruritus

-

Pain at sites of nodal disease

-

Back or bone pain

-

Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL) has a strong genetic component and has often previously been diagnosed in the family

-

Palpable, painless lymphadenopathy in the cervical area, axilla, or inguinal area

-

Involvement of the Waldeyer ring (back of the throat, including the tonsils) or occipital (lower rear of the head) or epitrochlear (inside the upper arm near the elbow) area

-

Splenomegaly and/or hepatomegaly

-

Superior vena cava syndrome may develop in patients with massive mediastinal lymphadenopathy

-

Central nervous system symptoms or signs may be due to paraneoplastic syndromes, including cerebellar degeneration, neuropathy, Guillain-Barre syndrome or multifocal leukoencephalopathy

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory tests include the following:

-

Complete blood cell count studies for anemia, lymphopenia, neutrophilia, or eosinophilia

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

-

Serum creatinine

-

Alkaline phosphatase

-

HIV testing, because HIV-infected persons are at 5- to 26-fold higher risk for developing Hodgkin lymphoma, and effective antiretroiviral treatment improves lymphoma-related survival [3] ; screening for hepatitis B and C should also be considered

-

Serum levels of cytokines (interleukin [IL]-6, IL-10) and soluble CD25 (IL-2 receptor) correlate with tumor burden, systemic symptoms, and prognosis

Imaging studies include the following:

-

Plain radiographs: Measurement of mediastinal mass in relationship to thoracic diameter on posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs remains the gold standard

-

Computed tomography: Chest radiography has been largely replaced by CT scanning; on CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, possible abnormal findings include enlarged lymph nodes, hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly, lung nodules or infiltrates, and pleural effusions

-

Positron emission tomography: Considered essential to the initial staging of Hodgkin lymphoma

A histologic diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma is always required. An excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended because the lymph node architecture is important for histologic classification.

When a patient presents with neck lymphadenopathy and risk factors for a head and neck cancer, a fine-needle aspiration is usually advised as the initial diagnostic step, followed by excisional biopsy if squamous cell histology is excluded.

Bone marrow biopsies are indicated in some cases. Bone marrow involvement is more common in elderly patients and those with advanced-stage disease, systemic symptoms, or a high-risk histology.

Central nervous system evaluation by lumbar puncture and magnetic resonance imaging should be performed if symptoms or signs of CNS involvement are present.

The Ann Arbor classification is used most often for Hodgkin lymphoma, as follows:

-

Stage I: A single lymph node area or single extranodal site

-

Stage II: 2 or more lymph node areas on the same side of the diaphragm

-

Stage III: Lymph node areas on both sides of the diaphragm

-

Stage IV: Disseminated or multiple involvement of the extranodal organs

See also the Medscape article Hodgkin Lymphoma Staging.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

General treatment principles include the following:

-

Radiation therapy

-

Induction chemotherapy

-

Salvage chemotherapy

-

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

See also Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment Protocols.

Published guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), [4] the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), [5] and the International Harmonization Project [6] provide consensus opinions from leading experts on evidence-based approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma. See Guidelines.

The radiation fields used in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma are generally defined as follows:

-

Involved-field radiation (IFRT): Radiation field that encompasses all of the clinically involved regions (eg, the mediastinum and the low-supraclavicular fields)

-

Involved-site radiation (ISRT): Radiation field that includes pre- and post-chemotherapy nodal volumes plus a 1.5-cm margin of healthy tissue; ISRT is largely replacing IFRT

-

Involved-node radiation (INRT): Radiation field that includes pre- and post-chemotherapy nodal volumes plus a 1-cm margin of healthy tissue

The following induction regimens are given as initial treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma:

-

MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone)

-

ABVD (Adriamycin [doxorubicin], bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine)

-

Stanford V (doxorubicin, vinblastine, mustard, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone)

-

BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone)

Brentuximab vedotin plus AVD is indicated as first-line therapy for previously untreated stage III-IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

When induction chemotherapy fails, or patients experience relapse, salvage chemotherapy is generally given. Salvage regimens incorporate drugs that are complementary to those that failed during induction therapy. Commonly used salvage regimens include the following:

-

ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide)

-

DHAP (cisplatin, cytarabine, prednisone)

-

ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin)

High-dose chemotherapy at doses that ablate the bone marrow is feasible with reinfusion of the patient's previously collected hematopoietic stem cells or infusion of stem cells from a donor source. Historically, hematopoietic stem cells have been obtained from bone marrow, but they are now typically obtained by pheresis of peripheral blood lymphocytes. A validated and relatively safe conditioning regimen for autologous transplantation is the BEAM regimen (carmustine [BCNU], etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan). [7]

Toxicities associated with treatment regimens include the following:

-

Hematologic toxicity: Anemia (need for transfusion), thrombocytopenia, increased risk of infection (febrile neutropenia); myelodyplasia or acute leukemia

-

Pulmonary toxicity, particularly if bleomycin or thoracic radiation are used; increased risk of lung cancer or fibrotic lung disease, particularly in smokers

-

Cardiac toxicity from anthracycline therapy; congestive heart failure from treatment; increased risk of coronary artery disease

-

Infectious: Long-term increased risk of infection from splenectomy (rarely done in current practice), long-term immunodeficiency from treatment effects

-

Cancer: Increased risk of secondary cancers, particularly breast cancer in young women treated with mediastinal radiation; increased risk of sarcomas in radiation fields

-

Neurologic: Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, muscular atrophy

-

Psychiatric: Depression and anxiety related to diagnosis and complications from treatment

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

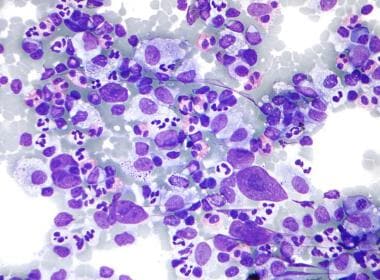

Hodgkin lymphoma is a potentially curable lymphoma with distinct histology, biologic behavior, and clinical characteristics. The disease is defined in terms of its microscopic appearance (histology) (see the image below) and the expression of cell surface markers (immunophenotype). (See Pathophysiology.)

Micrograph of Hodgkin lymphoma in a fine-needle aspiration lymph node specimen (field stain). Eosinophils, Reed-Sternberg cells, plasma cells, and histocytes can be seen.

Micrograph of Hodgkin lymphoma in a fine-needle aspiration lymph node specimen (field stain). Eosinophils, Reed-Sternberg cells, plasma cells, and histocytes can be seen.

Until the recently, Hodgkin lymphoma was known as Hodgkin's disease. The eponym honors the British physician Thomas Hodgkin, who published the first description of the disease in 1832. [8]

To diagnose Hodgkin lymphoma a histologic evaluation is always required, and an excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended for this purpose (see Workup). Various imaging studies are used to stage the patient.

Treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma is with multiagent chemotherapy, with or without radiation therapy. Treatment seeks to balance the risk of treatment failure with the risk of treatment side effects (see Treatment).

See also the Medscape article Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma.

Pathophysiology

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies Hodgkin lymphoma into five types. [1] Nodular sclerosing, mixed cellularity, lymphocyte depleted, and lymphocyte rich are the four types referred to as classical Hodgkin lymphoma. The fifth type, nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), is a distinct entity with unique clinical features and a different treatment paradigm.

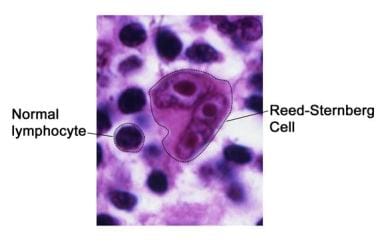

In classical Hodgkin lymphoma, the neoplastic cell is the Reed-Sternberg cell (see the image below). [9, 10] Reed-Sternberg cells comprise only 1-2% of the total tumor cell mass. The remainder is composed of a variety of reactive, mixed inflammatory cells consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.

A Reed-Sternberg cell in Hodgkin lymphoma. Reed-Sternberg cells are large, abnormal lymphocytes that may contain more than one nucleus. Image courtesy of National Cancer Institute.

A Reed-Sternberg cell in Hodgkin lymphoma. Reed-Sternberg cells are large, abnormal lymphocytes that may contain more than one nucleus. Image courtesy of National Cancer Institute.

Most Reed-Sternberg cells are of B-cell origin, derived from lymph node germinal centers but no longer able to produce antibodies. Hodgkin lymphoma cases in which the Reed-Sternberg cell is of T-cell origin are rare, accounting for 1-2% of classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

The Reed-Sternberg cells consistently express the CD30 (Ki-1) and CD15 (Leu-M1) antigens. CD30 is a marker of lymphocyte activation that is expressed by reactive and malignant lymphoid cells and was originally identified as a cell surface antigen on Reed-Sternberg cells. CD15 is a marker of late granulocytes, monocytes, and activated T-cells that is not normally expressed by cells of B lineage.

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma is classified into the following 4 types:

-

Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL)

-

Mixed-cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma (MCHL)

-

Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma (LDHL)

-

Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma (LRHL)

Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma

In NSHL, which constitutes 60-80% of all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma, the morphology shows a nodular pattern. Broad bands of fibrosis divide the node into nodules. The capsule is thickened. The characteristic cell is the lacunar-type Reed-Sternberg cell, which has a monolobated or multilobated nucleus, a small nucleolus, and abundant pale cytoplasm.

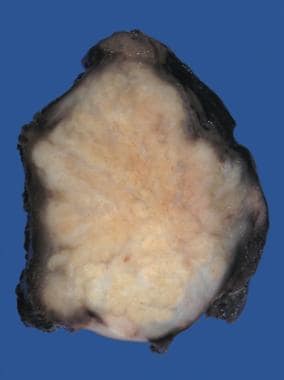

NSHL is frequently observed in adolescents and young adults. It usually involves the mediastinum (see the image below) and other supradiaphragmatic sites.

Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma of the mediastinum. The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the presence of distinct nodules on the cut surface of this lymph node.

Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma of the mediastinum. The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the presence of distinct nodules on the cut surface of this lymph node.

Mixed-cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma

In MCHL, which constitutes 15-30% of cases, the infiltrate is usually diffuse. Reed-Sternberg cells are of the classical type (large, with bilobate, double or multiple nuclei, and a large, eosinophilic nucleolus). MCHL commonly affects the abdominal lymph nodes and spleen. Patients with this histology typically have advanced-stage disease with systemic symptoms. MCHL is the histologic type most commonly observed in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma

LDHL constitutes less than 1% of cases. The infiltrate in LDHL is diffuse and often appears hypocellular. Large numbers of Reed-Sternberg cells and bizarre sarcomatous variants are present.

LDHL is associated with older age and HIV-positive status. Patients usually present with advanced-stage disease. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) proteins are expressed in many of these tumors. Many cases of LDHL diagnosed in the past were actually non-Hodgkin lymphomas, often of the anaplastic large-cell type.

Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma

LRHL constitutes 5% of cases. In LRHL, Reed-Sternberg cells of the classical or lacunar type are observed, with a background infiltrate of lymphocytes. It requires immunohistochemical diagnosis. Some cases may have a nodular pattern. Clinically, the presentation and survival patterns are similar to those for MCHL.

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) constitutes 5% of cases. It is a distinct clinical entity and is not considered part of the classical Hodgkin lymphoma type. Typical Reed-Sternberg cells are either infrequent or absent in NLPHL. Instead, lymphocytic and histiocytic (L&H) cells, or "popcorn cells" (their nuclei resemble an exploded kernel of corn), are seen within a background of inflammatory cells, which are predominantly benign lymphocytes (see the image below). Unlike Reed-Sternberg cells, L&H cells are positive for B-cell antigens, such as CD20, and are negative for CD15 and CD30.

Very high magnification micrograph of nodular lymphoctye predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), with a popcorn-shaped Reed-Sternberg cell (hematoxylin and eosin).

Very high magnification micrograph of nodular lymphoctye predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), with a popcorn-shaped Reed-Sternberg cell (hematoxylin and eosin).

A diagnosis of NLPHL needs to be supported by immunohistochemical studies, because it can appear similar to LRHL or even some non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Etiology

The etiology of Hodgkin lymphoma is unknown. Infectious agents, particularly Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), may be involved in the pathogenesis. [11, 12] Depending on the study, data show that up to 30% of cases of classical Hodgkin lymphoma may be positive for EBV proteins. [13] In addition, a case control study supports an increased risk of classical Hodgkin lymphoma after EBV infection, with a risk of approximately 1 in 1000 cases. [14]

The incidence of EBV positivity varies with subtype. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) rarely expresses EBV proteins, [15] whereas in classical Hodgkin lymphoma, EBV positivity is most common in the mixed-cellularity variant. [16] However, the exact mechanism by which EBV can lead to Hodgkin lymphoma is not known.

HIV-positive patients also have a higher incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma compared with HIV-negative patients. However, Hodgkin lymphoma is not considered an AIDS-defining neoplasm.

Genetic predisposition plays a role in the pathogenesis of Hodgkin lymphoma. Approximately 1% of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma have a family history of the disease, and siblings of an affected individual have a 3- to 7-fold increased risk of developing the disease. [17] Most evidence for a genetic etiology has been established in the distinct subtype of nonsclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL). NSHL has been shown to be one of the most heritable types of neoplasm, with a 100-fold increased risk in identical twins. [18, 19]

There is evidence that NSHL may result from an atypical immune response to a virus or other trigger, in an individual with a genetic predisposition to such a response. [20] For decades, specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II genotypes, including HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1, have been known to be associated with NSHL, and this has been confirmed by genome-wide association studies. [21] Several single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the 6p21.32 region, which is rich in genes associated with immune function, have also been associated with NSHL risk. [22]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Information regarding the incidence and mortality of Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States can be found at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database Website. The NCI reports that age-adjusted rates for new Hodgkin lymphoma cases have been falling on average 2.3% each year over the last 10 years. As of 2016-2020, the age-adjusted annual incidence is 2.5 cases per 100,000 population. Death rates have decreased slowly but steadily in recent decades, but were stable at 0.3 per 100,000 population per year over 2016-2020. [23]

Data are also collected by the American Cancer Society (ACS). The ACS estimates that 8830 new cases of Hodgkin lymphoma will be diagnosed in 2023, and 900 deaths will occur. [24]

International statistics

In Europe and other developed countries, the incidence parallels US data. [25, 26] United Kingdom data from 2016-2018 show a crude incidence rate of 3.2 cases per 100,000 population (3.8 cases per 100,000 males and 2.7 cases per 100,000 females). Since the early 1990s, incidence rates of Hodgkin lymphoma in the UK have risen 37%. [27]

Race-, sex-, and age-related differences in incidence

Hodgkin lymphoma incidence rates in the United States vary by race and sex. The highest incidence is in non-Hispanic Whites; the lowest incidence is in American Indians/Alaska Natives and Asians/Pacific Islanders. In general, incidence is higher in males than in females. The sex predilection is most pronounced in children, with 85% of cases affecting boys. [23]

The incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma varies with age, with a clear bimodal distribution that is consistent across most countries and studies. The initial peak is in young adults (15-34 years); Hodgkin lymphoma is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in teens ages 15 to 19. The second peak is in older adults (> 55 years). [28] There is also a difference in subtype based on age, with young adults having nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL) and older adults tending to have mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma (MCHL).

Prognosis

Patient prognosis is largely based on the stage of the disease and various prognostic factors, which may be defined differently across various major cooperative groups (eg, German Hodgkin's Study Group [GHSG] vs European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EORTC] and others). [29] (See also Staging.)

The SEER data report an 86.2% overall 5-year survival rate from 2006-2012. [23] Table 1 summarizes the stage distribution and 5-year relative survival at diagnosis for the same period for all races and both sexes. [23] In addition to the stage of the disease, many factors contribute to the likelihood of survival from Hodgkin lymphoma (see Staging). Factors that influence prognosis include patient age, presence or absence of B symptoms, stage of disease, and elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate. [30]

Table 1. Stage Distribution and 5-Year Relative Survival by Stage at Diagnosis for All Races and Both Sexes: 2011-2015 (Open Table in a new window)

Stage at Diagnosis |

Stage Distribution, % |

5-year Relative Survival, % |

Stage I (only in originating layer of cells) |

15 |

92.3 |

Stage II (confined to primary site) |

40 |

93.4 |

Stage III (spread to regional lymph nodes) |

21 |

83.0 |

Stage IV (cancer has metastasized) |

20 |

72.9 |

Unstaged |

4 |

82.7 |

Source: National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: Hodgkin lymphoma. Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/hodg.html. Accessed: September 12, 2018 |

||

The most commonly used prognostic system is the International Prognostic System (IPS), which uses the following variables to The most commonly used prognostic system is the International Prognostic System (IPS), which uses the following variables to determine prognosis [31] :

-

Serum albumin less than 4 g/dL

-

Hemoglobin less than 10.5 g/dL

-

Male sex

-

Age of 45 years or older

-

Stage IV disease (Ann Arbor classification)

-

White blood cell (WBC) count greater than 15,000/mm3

-

Absolute lymphocyte count less than 600/mm3, less than 8% of the total WBC count, or both

Each of the above variables is assigned 1 point. The total number of points for prognostic factors is used to determine risk. When applied to a group of 5141 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma the IPS produced the following groups of 5-year survival rates [31] :

-

0 prognostic factors: 84%

-

1 prognostic factor: 77%

-

2 prognostic factors: 67%

-

3 prognostic factors: 60%

-

4 prognostic factors: 51%

-

5 or more prognostic factors: 42%

These results have been validated in other populations as well, including in patients undergoing stem cell transplant. [32, 33] However this scoring system is most applicable to patients with advanced-stage disease (stages III and IV).

Patient Education

Before beginning treatment, patients with Hodgkin lymphoma should be counseled about the potential complications of therapy, including the risk of cardiac disease, lung toxicity, and secondary cancers. Patients should also be apprised of the potential loss of fertility that may arise from treatments such as MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) chemotherapy, escalated BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) chemotherapy, and pelvic irradiation, so that they may explore fertility-preserving options such as sperm banking, oral contraceptive use, or oophoropexy. Although less likely, infertility can also occur with ABVD therapy (Adriamycin [doxorubicin], bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine).

Female patients who have received chest radiation therapy should be encouraged to perform regular breast self-examinations. All patients should be counseled on health habits that may help reduce the risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease, including avoidance of smoking, control of lipids, and the use of sunscreen.

Although splenectomy is uncommon with modern therapy, any patient who has undergone this procedure needs to be counseled about vaccination needs and their long-term risk of infection.

Patients should understand the risk of psychosocial problems that may affect survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma. Consultations with social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists may be helpful.

For patient education information, see Understanding Hodgkin Lymphoma -- the Basics.

-

Micrograph of Hodgkin lymphoma in a fine-needle aspiration lymph node specimen (field stain). Eosinophils, Reed-Sternberg cells, plasma cells, and histocytes can be seen.

-

Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma of the mediastinum. The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the presence of distinct nodules on the cut surface of this lymph node.

-

A Reed-Sternberg cell in Hodgkin lymphoma. Reed-Sternberg cells are large, abnormal lymphocytes that may contain more than one nucleus. Image courtesy of National Cancer Institute.

-

Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma showing both mononucleate and binucleate Reed-Sternberg cells in a background of inflammatory cells (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x200).

-

Very high magnification micrograph of nodular lymphoctye predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), with a popcorn-shaped Reed-Sternberg cell (hematoxylin and eosin).

-

A positron emission tomography (PET) scan obtained with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) that shows increased FDG uptake in a mediastinal lymph node.

-

A computed tomography (CT) scan showing bulk disease in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma.

-

This computed tomography scan is from a 46-year patient with Hodgkin lymphoma at the level of the neck. Enlarged lymph nodes are visible on the left side of the neck (red-shaded region).

-

This image depicts a computed tomography (CT) scan, positron-emission tomography (PET) scan, and maximum intensity projection (MIP) PET scan from a patient with histologically proven Hodgkin lymphoma.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Approach Considerations

- Goals of Therapy and Response Assessment

- Radiation Therapy

- Induction Chemotherapy Regimens

- Salvage Chemotherapy Regimens

- Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

- Treatment of Early-Stage, Low-Risk Disease

- Treatment of Early-Stage Disease with Unfavorable Factors

- Treatment of Advanced Disease

- Treatment of Nodular Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Treatment in HIV-Infected Patients

- Treatment of Refractory or Relapsed Disease

- Complications of Therapy

- Long-Term Monitoring

- Future Directions

- Show All

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Medication Summary

- Antineoplastics, Alkylating

- Antineoplastics, Antibiotic

- Antineoplastics, Vinca Alkaloid

- Antineoplastics, Podophyllotoxin Derivatives

- Antineoplastics, Alkylating, DMARDs, Immunomodulators

- Immunosuppressants; Antineoplastics, Antimetabolite; DMARDs, Immunomodulators

- Antineoplastics, Anthracyclines

- Antineoplastics, Antimicrotubular

- PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

- Corticosteroids

- Show All

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- Tables

- References