Practice Essentials

Allergic rhinitis is a common health problem for which many patients do not seek appropriate medical care. Although not a life-threatening condition in most cases, it has a substantial impact on public health and the economy. The diagnosis of allergic rhinitis is based on the history, and tests are used only to confirm atopy. The three basic approaches to the treatment of allergies are (1) avoidance, (2) pharmacotherapy, and (3) immunotherapy.

A 2016 study by Mudarri estimated that the annual societal cost of allergic rhinitis in the United States, in 2014 dollars, is $24.8 billion. [1]

Signs and symptoms of allergic rhinitis

Patients with allergic rhinitis frequently grimace and twitch their face, in general, and nose, in particular, because of itchy mucus membranes. Chronic mouth breathing secondary to nasal congestion can result in the typical adenoid facies.

Patients may have injected conjunctiva, increased lacrimation, and long, silky eyelashes. Dennie-Morgan lines (creases in the lower eyelid skin) and allergic shiners (dark discoloration below the lower eyelids) caused by venous stasis may be present.

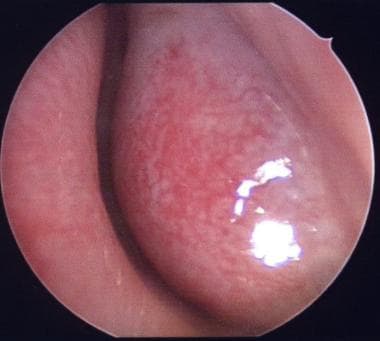

With regard to the nose, a transverse nasal crease may be present because of the patient's repeated lifting of the nasal tip to relieve itching and open the nasal airway. The turbinates are frequently hypertrophic and covered with a boggy, pale or bluish mucosa. Nasal secretions can range from clear and profuse to stringy and mucoid.

The mouth of an individual with allergic rhinitis may have a high, arched palate; narrow premaxilla; and receding chin, secondary to long-term mouth breathing. The posterior oropharynx may be granular because of irritation from persistent postnasal discharge.

Workup in allergic rhinitis

The diagnosis of allergic rhinitis is based on the history, and tests are used only to confirm atopy. In nasal cytologic studies, the presence of eosinophils and goblet cells is generally suggestive of allergy, whereas the presence of neutrophils and bacteria is characteristic of infection.

Skin testing is generally considered to be the standard of allergy workup. The classic wheal-and-flare responses result from the interaction between the antigen and sensitized mast cells in the skin.

In contrast to total immunoglobulin E (IgE), which has a poor clinical correlation, antigen-specific IgE antibodies are important in the diagnosis of inhalant allergy.

Management

Treatment should start with avoidance of allergens and with environmental controls. In almost all cases, however, some pharmacotherapy is needed because the patient is either unwilling or unable to avoid allergens and to control the occasional exacerbations of symptoms. For patients with a severe allergy that is not responsive to environmental controls and pharmacotherapy or for those who do not wish to use medication for a lifetime, immunotherapy may be offered.

Although allergic rhinitis is a medical condition, adjunctive surgery may be offered to alleviate obstructive symptoms in appropriate individuals. Examples are nasal polypectomy in the patients who have severe polyposis and various inferior turbinate reduction maneuvers in patients who have nasal obstruction caused by turbinate hypertrophy that persists despite maximal medical therapy. [2]

Pathophysiology

Because the nose is the most common port of entry for allergens, in patients with allergies, signs and symptoms of allergic rhinitis, not surprisingly, are the most common complaints.

Four types of hypersensitivity responses exist, as initially classified by Gell and Coombs and later modified by Shearer and Huston. Individuals with allergic rhinitis are thought to have type I reactions.

After initial exposure to an antigen, antigen-processing cells (macrophages) present the processed peptides to T helper cells. Upon subsequent exposure to the same antigen, these cells are stimulated to differentiate into either more T helper cells or B cells. The B cells may further differentiate into plasma cells and produce immunoglobulin E (IgE) specific to that antigen. Allergen-specific IgE molecules then bind to the surface of mast cells, sensitizing them.

Further exposures result in the bridging of 2 adjacent IgE molecules, leading to the release of preformed mediators from mast cell granules. These mediators (ie, histamine, leukotrienes, kinins) cause early-phase symptoms such as sneezing, rhinorrhea, and congestion. Late-phase reactions begin 2-4 hours later and are caused by newly arrived inflammatory cells. Mediators released by these cells prolong the earlier reactions and lead to chronic inflammation.

A study by Shahsavan et al found that patients with moderate to severe persistent allergic rhinitis demonstrated significantly greater interleukin 22 (IL-22) and IL-17A production than did healthy controls, suggesting that the development of persistent allergic rhinitis is influenced by these cytokines. Moreover, a correlation was found between IL-22 and IL-17A serum levels, along with the mean number of IL-22– and IL-17A–positive cells in the nasal mucosa, and specific IgE levels, nasal eosinophil count, and total nasal symptom score (TNSS). [3]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Approximately 39 million Americans are reported to have allergic rhinitis. From various studies, 17-25% of the population in the United States are estimated to have the condition.

Mortality/Morbidity

Allergic rhinitis is frequently associated with otitis media, rhinosinusitis, and asthma, either as a precipitating and/or aggravating factor or a symptomatic comorbid condition.

Allergic rhinitis can significantly decrease the quality of life and impair social and work functions, either directly or indirectly, because of the adverse effects of medications taken to relieve the symptoms.

A study by Romano et al indicated that sleep problems in adults with perennial allergic rhinitis not only are common, but negatively affect daily functioning in these individuals. In an analysis of 511 adults with perennial allergic rhinitis (either self reported or physician diagnosed), the investigators found that sleep problems were reported by 66.0% of subjects, and that such problems occurred more frequently in persons with both allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma (78.1%) than in those with allergic rhinitis alone (54.7%). Moreover, sleep difficulties significantly impacted daytime functioning in 33.3% of individuals with allergic rhinitis by itself, versus 47.0% of those with a combination of allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma. [4]

A literature review by Rodrigues et al reported an apparent association between allergic rhinitis and an increased risk of depression and anxiety. [5]

Sex

Males and females tend to be affected by allergic rhinitis in fairly equal proportions. A study by Cazzoletti et al found gender-associated age-based differences in the prevalence of self-reported allergic and nonallergic rhinitis, with allergic rhinitis showing an age-based decrease in prevalence that was comparable in males and females (from 26.6% in persons aged 20-44 years to 15.6% in persons aged 65-84 years), and nonallergic rhinitis showing an age-based decrease in prevalence among females (from 12.0% in females aged 20-44 years to 7.5% in females aged 65-84 years) and roughly the same prevalence in younger and older males (10.2% in males aged 20-44 years and 11.1% in males aged 65-84 years). [6]

Age

Allergic rhinitis appears mainly to affect individuals younger than 45 years.

The condition may begin to appear in patients as young as 2 years and usually reaches a peak in those aged 21-30 years.

It then tends to remain stable or slowly decrease until patients are aged 60 years, when again the prevalence may increase slightly.

-

Boggy inferior turbinate in an allergic patient.