History of the Procedure

Chinese physicians were the first to describe the technique of repairing cleft lip. The early techniques involved simply excising the cleft margins and suturing the segments together. The evolution of surgical techniques during the mid-17th century resulted in the use of local flaps for cleft lip repair. These early descriptions of local flaps for the treatment of cleft lip form the foundation of surgical principles used today.

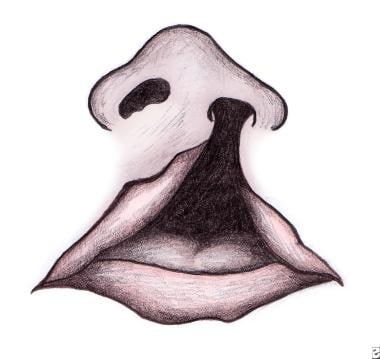

Tennison introduced the triangular flap technique of unilateral cleft lip repair, which preserved the Cupid's bow in 1952. The geometry of the triangular flap was described by Randall, who popularized this method of lip repair. Millard described the technique of rotating the medial segment and advancing the lateral flap; thus, preserving the Cupid's bow with the philtrum. [1] This technique has resulted in improved outcomes in cleft lip repair. See the image below.

Problem

Cleft lip is among the most common of congenital deformities. The condition is due to insufficient mesenchymal migration during primary palate formation in the fourth through seventh week of intrauterine life. This results in disfigurement and distortion of the upper lip and nose. Cleft lip may be associated with syndromes that include anomalies involving multiple organs. Patients may have impaired facial growth, dental anomalies, and speech disorders (if a cleft palate is present), and they may experience late psychosocial difficulties.

A study by Gallagher et al indicated that in children with isolated unilateral cleft lip with or without cleft palate, achievement scores and special education service usage were similar between those with right-sided clefts and controls. However, in children with left-sided clefts, all evaluated domain scores were lower than those of their classmates by 4-6 percentiles, special education service usage was greater by 6 percentage points, and reading scores were lower than in children with right-sided clefts by almost 7 percentiles. [2]

A study by Datana et al indicated that the prevalence of upper cervical vertebrae anomalies is more than three times greater in persons with cleft lip/palate than in those without the condition. The prevalence was 20.3% in the cleft group overall, compared with 6.4% in the control group. In patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate, the prevalence was 22.2%, while in those with bilateral cleft lip and palate, the prevalence was 19.1%, and in patients with cleft palate only, the prevalence of upper cervical vertebrae anomalies was 16.6%. The study involved 128 patients with cleft lip/palate and 125 controls. [3]

Epidemiology

Frequency

The incidence of cleft lip in the White population is approximately 1 in 1000 live births. The incidence in the Asian population is twice as great, whereas that in the Black population is less than half as great. [4] Male children are affected more often than female children. A study by Michalski et al found that among isolated, noncardiac birth defects, cleft lip had one of the highest male-to-female ratios. The study involved 25,952 infants from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (1997-2009), with male preponderance among isolated, noncardiac birth defects being greatest for craniosynostosis (2.12), cleft lip with cleft palate (2.01), and cleft lip alone (1.78). [5]

Isolated unilateral clefts occur twice as frequently on the left side as on the right and are 9 times more common than bilateral clefts. Combined cleft lip and palate is the most common presentation (50%), followed by isolated cleft palate (30%), and isolated cleft lip or cleft lip and alveolus (20%). Fewer than 10% of clefts are bilateral.

For parents with cleft lip and palate or for a child with cleft lip and palate, the risk of having a subsequent affected child is 4%. The risk increases to 9% with 2 previously affected children. In general, the risk to subsequent siblings increases with the severity of the cleft.

Etiology

Little evidence exists that links isolated clefts to exposure to any single teratogenic agent. An exception is the anticonvulsant drug, phenytoin. The use of phenytoin during pregnancy is associated with a 10-fold increase in the incidence of cleft lip.

Other exceptions may be certain air pollutants. A study by Krakauer et al indicated that air pollution in the United States is associated with an increased incidence of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate (NSCLP). Looking at the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Air Quality System data, the investigators examined the effect of common pollutants, including benzene, sulfur dioxide (SO2), particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5), PM10, ozone (O3), and carbon monoxide (CO), on the incidence of NSCLP per 1000 live births between 2016 and 2020, culled from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Vital Statistics System database. The study reported that SO2 and PM2.5 raised the incidence of NSCLP, the coefficient estimates for these being 0.60 and 0.20, respectively. However, no significant association was found between pollutants and isolated nonsyndromic cleft palate. [6]

The incidence of cleft lip in infants born to mothers who smoke during pregnancy is twice that of those born to nonsmoking mothers. Syndromic clefts are those associated with malformations in other developmental regions, with reported frequencies ranging from 5-14%.

The most commonly recognized syndrome associated with clefts of the lip and palate is Van der Woude syndrome. This syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by clefts of the lip and/or palate and blind sinuses, or pits, of the lower lip. Clefts of the secondary palate alone are far more likely to be associated with syndromes than are clefts involving the lip alone or the lip and palate. Most cases of lip clefts are nonsyndromic and believed to be either multifactorial in origin or the result of changes at a major single-gene locus.

Pathophysiology

Development of the upper lip is characterized by fusion of the maxillary prominences with the lateral and medial nasal prominences. This process starts during the fourth week of gestation and is completed by the seventh week. Failure of mesenchymal migration to unite one or both of the maxillary prominences with the medial nasal prominences results in a unilateral or bilateral cleft of the lip, respectively.

Classification

No universally accepted classification scheme exists for clefts of the lip and palate. Veau categorized clefts into 4 classes, as follows:

Clefts of the soft plate alone

Clefts of the soft and hard palate

Complete unilateral clefts of the lip and palate

Complete bilateral clefts of the lip and palate

This classification scheme does not provide a means of classifying clefts of the lip alone and ignores incomplete clefts. The Kernahan stripped–Y classification allows the description of the lip, the alveolus, and the palate. In this classification, the incisive foramen defines the boundary between clefts of the primary palate (lip and premaxilla) and those of the secondary palate.

Presentation

Clefts of the lip may manifest as microform, incomplete, or complete clefts. Microform clefts are characterized by a vertical groove and vermilion notching with varying degrees of lip shortening. Unilateral incomplete lips manifest varying degrees of lip disruption associated with an intact nasal sill or Simonart band (a band of fibrous tissue from the edge of the red lip to the nostril floor). Complete clefts of the lip are characterized by disruption of the lip, alveolus, and nasal sill.

Bilateral clefts are almost always associated with cleft palate, with 86% of patients with such clefts of the lip presenting with palatal clefts. Unilateral clefts of the lip are associated with palatal clefts in 68% of cases. Nasal regurgitation during suckling may indicate an associated cleft of the palate. All infants with clefts of the lip should have a complete head and neck examination, including careful examination of the palate as far as the tip of the uvula. The presence of a bifid uvula, a translucent central zone in the velum, and a detectable notch of the posterior border of the hard palate indicate submucosal palatal cleft.

All patients with clefts are best referred to multidisciplinary cleft lip and palate centers. Persistent otitis media and middle ear effusions are associated with palatal clefts and warrant regular follow-up care. Depending on the preference of the surgical centers, the otolaryngologist may elect to perform myringotomy before or after definitive cleft lip and palate repair.

Most cases of lip clefts are nonsyndromic. Parents should be reassured and advised sensitively. At the initial visit, review feeding techniques carefully. For the infant, breastfeeding and the capacity to suck are difficult. However, breastfeeding may be possible with isolated clefts of the lip and the alveolus. For infants with palatal clefts, a variety of special bottles and nipples are available. Crosscut soft nipples made for premature infants facilitate feeding of infants with cleft palate. At the conclusion of the initial consultation, the parents and the infant should be comfortable with the feeding method.

Indications

Clefts of the lip are usually repaired in early infancy. Reassure and advise the parents that operative intervention is best carried out at age 2-3 months. The rule of 10 serves as a safe guideline, ie, body weight should be approximately 10 lb, the hemoglobin concentration 10 g/dL, and age greater than 10 weeks.

Relevant Anatomy

The typical unilateral complete cleft lip deformity results from both a deficiency and a displacement of the soft tissues, the underlying bony structures, and cartilaginous structures. An imbalance of the normal muscular forces acting upon the maxilla results in an outward rotation of the premaxillary-bearing medial segment and posterolateral displacement of the smaller lateral segment.

The inferior edge of the anterior nasal septum is displaced out of the vomerine groove into the noncleft nostril, and the anterior septum leans laterally over the cleft. The overlying columella invariably is short on the cleft side and distorted by the displaced caudal septum. In the nasal tip, the alar cartilage is characteristically deformed, and the medial crus is displaced posteriorly. The dome is separated from that of the noncleft side, and the lateral crus is flattened and stretched across the cleft. The axis of the nostril on the cleft side is characteristically oriented in the horizontal plane. This position is in contrast to the normal vertical axis of the nostril on the opposite side.

The muscular fibers of the orbicularis oris do not decussate transversely as in the normal lip; rather, they course obliquely upward, paralleling the cleft margin toward the alar base on the lateral side of the cleft and toward the base of the columella medially. The philtrum on the cleft side is short, and the presumptive Cupid's bow peak is displaced superiorly. The vermilion is deficient on the cleft side of the medial element.

Complete bilateral clefts of the lip result from failure of the premaxillary segment to fuse with the lateral maxillary segments. Subsequent forward growth of the premaxilla, attached only to the vomer above, leads to its projection beyond the lateral segments. Within the isolated prolabium, the skin is foreshortened vertically, the white roll is underdeveloped, and the vermilion is deficient. The prolabium lacks muscle fibers, and the philtral ridges, the central philtral dimple, and Cupid's bow are absent. The bilateral cleft nasal deformity is characterized by flaring of the alar bases and wide separation of the domal segments of the alar cartilages. The columella is markedly shortened, causing the nasal tip to be depressed.

Contraindications

All surgical candidates are screened for safety prior to repair. Coexisting medical conditions that would result in cardiopulmonary complications, bleeding disorders, infection, and/or malnutrition are all contraindications to surgery.

-

Cleft lip.

-

Cleft lip.

-

Cleft lip. Postoperative view of the same patient as in Image 2.