Practice Essentials

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) is usually a late complication of an infection of the central face or paranasal sinuses. Other causes include bacteremia, trauma, and infections of the ear or maxillary teeth. CST is generally a fulminant process with high rates of morbidity and mortality.

Signs and symptoms

Patients generally have sinusitis or a midface infection (most commonly a furuncle) for 5-10 days. In as many as 25% of cases in which a furuncle is the precipitant, it will have been manipulated in some fashion (eg, squeezing, surgical incision).

Headache is the most common presentation symptom and usually precedes fevers, periorbital edema, and cranial nerve signs. The headache is usually sharp, increases progressively, and is usually localized to the regions innervated by the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the fifth cranial nerve.

Diagnosis

CST is a clinical diagnosis and lab studies are seldom specific. Most patients exhibit a polymorphonuclear leukocytosis, often marked with a shift toward immature forms. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid is consistent with either a parameningeal inflammation or frank meningitis. Blood culture results generally are positive for the offending organism.

Management

The mainstay of therapy for CST is early and aggressive antibiotic administration. Although S aureus is the usual cause, broad-spectrum coverage for gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms should be instituted pending the outcome of cultures.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should include a penicillinase-resistant penicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin. If dental infection or other anaerobic infection is suspected, an anaerobic coverage should also be added.

IV antibiotics are recommended for a minimum of 3-4 weeks.

Background

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) was initially described by Bright in 1831 as a complication of epidural and subdural infections. The dural sinuses are grouped into the sagittal, lateral (including the transverse, sigmoid, and petrosal sinuses), and cavernous sinuses. Because of its complex neurovascular anatomic relationship, cavernous sinus thrombosis is the most important of any intracranial septic thrombosis. [1] Cavernous sinus thrombosis is usually a late complication of an infection of the central face or paranasal sinuses. Other causes include bacteremia, trauma, and infections of the ear or maxillary teeth. Cavernous sinus thrombosis is generally a fulminant process with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Fortunately, the incidence of cavernous sinus thrombosis has been decreased greatly with the advent of effective antimicrobial agents.

Pathophysiology

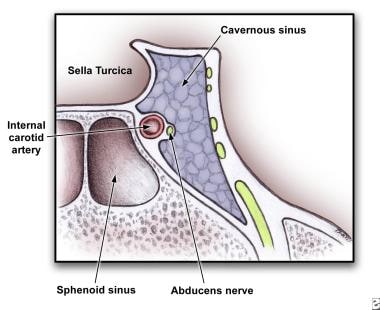

The cavernous sinuses are irregularly shaped, trabeculated cavities located at the base of the skull. The cavernous sinuses are the most centrally located of the dural sinuses and lie on either side of the sella turcica. These sinuses are just lateral and superior to the sphenoid sinus and are immediately posterior to the optic chiasm, as depicted in the image below. Each cavernous sinus is formed between layers of the dura mater, and multiple connections exist between the 2 sinuses.

Anatomy of cross section of cavernous sinus showing close proximity to cranial nerves and sphenoid sinus.

Anatomy of cross section of cavernous sinus showing close proximity to cranial nerves and sphenoid sinus.

The cavernous sinuses receive venous blood from the facial veins (via the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins) as well as the sphenoid and middle cerebral veins. They, in turn, empty into the inferior petrosal sinuses, then into the internal jugular veins and the sigmoid sinuses via the superior petrosal sinuses. This complex web of veins contains no valves; blood can flow in any direction depending on the prevailing pressure gradients. Since the cavernous sinuses receive blood via this distribution, infections of the face including the nose, tonsils, and orbits can spread easily by this route.

The internal carotid artery with its surrounding sympathetic plexus passes through the cavernous sinus. The third and fourth cranial nerves are attached to the lateral wall of the sinus. The ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the fifth cranial nerve are embedded in the wall. The sixth cranial nerve follows a more medial course in close approximation to the internal carotid, as depicted in the image above.

This intimate juxtaposition of veins, arteries, nerves, meninges, and paranasal sinuses accounts for the characteristic etiology and presentation of cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST). CST is more commonly seen with sphenoid and ethmoid and to a lesser degree with frontal sinusitis.

Staphylococcus aureus accounts for approximately 70% of all infections. Streptococcus pneumoniae, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes can also be seen. Fungi are a less common pathogen and may include Aspergillus and Rhizopus species.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Occurrence of cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) has always been low, with only a few hundred case reports in the medical literature. The majority of these date from before the modern antibiotic era. One review of the English-language literature found only 88 cases from 1940-1988.

Mortality/Morbidity

Prior to the advent of effective antimicrobial agents, the mortality rate from CST was effectively 100%. Typically, death is due to sepsis or central nervous system (CNS) infection. With aggressive management, the mortality rate is now less than 30%. Morbidity, however, remains high, and complete recovery is rare. Roughly one sixth of patients are left with some degree of visual impairment, and one half have cranial nerve deficits. These mortality and morbidity rates may be due to delayed diagnosis without prompt surgical drainage and antibiotic administration.

Age

All ages are affected, with a mean of 22 years.

Prognosis

Mortality rate for cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) is as high as 30%; the majority of survivors suffer permanent sequelae.

-

Anatomy of cross section of cavernous sinus showing close proximity to cranial nerves and sphenoid sinus.