Practice Essentials

Acetaminophen is one of the most commonly used oral analgesics and antipyretics. [1] It has an excellent safety profile when administered in proper therapeutic doses, but hepatotoxicity can occur after overdose or when misused in at-risk populations. In the United States, acetaminophen toxicity has replaced viral hepatitis as the most common cause of acute liver failure. [2]

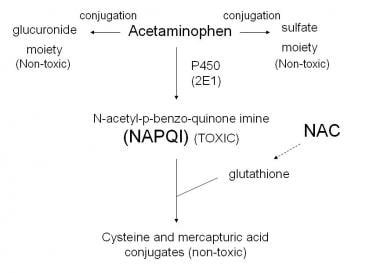

Acetaminophen metabolism occurs primarily in the liver and is illustrated in the image below.

Acetaminophen metabolism. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acetaminophen_metabolism.jpg).

Acetaminophen metabolism. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acetaminophen_metabolism.jpg).

Signs and symptoms

Most patients who overdose on acetaminophen will initially be asymptomatic, as clinical symptoms of end-organ toxicity do not manifest until 24-48 hours after an acute ingestion. Therefore, to identify a patient who may be at risk of hepatoxicity, the clinician should determine the time(s) of ingestion, the quantity, and the formulation of acetaminophen ingested.

Minimum toxic doses of acetaminophen for a single ingestion, posing significant risk of severe hepatotoxicity, are as follows:

-

Adults: 7.5-10 g

-

Children: 150 mg/kg; 200 mg/kg in healthy children aged 1-6 years

The clinical course of acetaminophen toxicity generally is divided into four phases. Physical findings may vary, depending on the degree of hepatotoxicity.

Phase 1

-

0.5-24 hours after ingestion

-

Patients may be asymptomatic or report anorexia, nausea or vomiting, and malaise

-

Physical examination may reveal pallor, diaphoresis, malaise, and fatigue

Phase 2

-

18-72 h after ingestion

-

Patients develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting

-

Right upper quadrant tenderness may be present

-

Tachycardia and hypotension may indicate volume losses

-

Some patients may report decreased urinary output (oliguria)

Phase 3: Hepatic phase

-

72-96 h after ingestion

-

Patients have continued nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and a tender hepatic edge

-

Hepatic necrosis and dysfunction may manifest as jaundice, coagulopathy, hypoglycemia, and hepatic encephalopathy

-

Acute kidney injury develops in some critically ill patients

-

Death from multiorgan failure may occur

Phase 4: Recovery phase

-

4 d to 3 wk after ingestion

-

Patients who survive critical illness in phase 3 have complete resolution of symptoms and complete resolution of organ failure

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The serum acetaminophen concentration is the basis for diagnosis and treatment. A diagnostic serum concentration is helpful, even in the absence of clinical symptoms, because clinical symptoms are delayed. The Rumack-Matthew nomogram interprets the acetaminophen concentration (in micrograms per milliliter), in relation to time (in hours) after ingestion, and predicts possible hepatotoxicity after single, acute ingestions of acetaminophen.

Recommended serum studies are follows:

-

Liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST]), bilirubin [total and fractionated], alkaline phosphatase)

-

Prothrombin time (PT) with international normalized ratio (INR)

-

Glucose

-

Kidney function studies (electrolytes, BUN, creatinine)

-

Lipase and amylase (in patients with abdominal pain)

-

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (in females of childbearing age)

-

Salicylate level (in patients with concern of co-ingestants)

-

Arterial blood gas and ammonia (in clinically compromised patients)

Additional recommended studies are as follows:

-

Urinalysis (to check for hematuria and proteinuria)

-

ECG (to detect additional clues for co-ingestants)

In patients with mental status changes, strongly consider serum ammonia levels and CT scanning of the brain. Laboratory findings in the phases of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity are as follows:

-

Phase 1: Approximately 12 hours after an acute ingestion, liver function studies show a subclinical rise in serum transaminase concentrations (ALT, AST)

-

Phase 2: Elevated serum ALT and AST, PT, and bilirubin concentration; renal function abnormalities may also be present and indicate nephrotoxicity

-

Phase 3: Severe hepatotoxicity is evident on serum studies; hepatic centrilobular necrosis is diagnosed on liver biopsy

Rumack-Matthew nomogram

-

Used to interpret plasma acetaminophen values to assess hepatotoxicity risk after a single, acute ingestion

-

Nomogram tracking begins 4 hours after ingestion (time when acetaminophen absorption is likely to be complete) and ends 24 hours after ingestion

-

About 60% of patients with values above the "probable" line develop hepatotoxicity

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Gastrointestinal decontamination agents can be used in the emergency setting during the immediate postingestion time frame. A single dose of activated charcoal may be considered in patients who are alert and able to control their airway, and who present promptly—ideally, within 1 hour—post ingestion. This time frame can be extended if the patient has ingested an acetaminophen-based sustained-release medication or if the ingestion includes agents that are known to slow gastric emptying, such as opioids. Patients with acetaminophen concentrations below the “possible" line for hepatotoxicity on the Rumack-Matthew nomogram may be discharged home after they are medically cleared.

Admit patients with acetaminophen concentration above the "possible" line on the Rumack-Matthew nomogram for treatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC). NAC is nearly 100% hepatoprotective when it is given within 8 hours after an acute acetaminophen ingestion, but can be beneficial in patients who present more than 24 hours after ingestion. NAC is approved for both oral and IV administration.

The FDA-approved regimen for oral administration of NAC is as follows:

-

Loading dose of 140 mg/kg

-

17 doses of 70 mg/kg given every 4 hours

-

Total treatment duration of 72 hours

The IV formulation of NAC (Acetadote) is commonly used in many institutions for the treatment of acetaminophen ingestion. Use of the IV formulation of NAC is preferred in the following situations:

-

Altered mental status

-

GI bleeding and/or obstruction

-

A history of caustic ingestion

-

Potential toxicity in a pregnant woman

-

Inability to tolerate oral NAC because of emesis refractory to proper use of antiemetics

Surgical evaluation for possible liver transplantation is indicated for patients who have severe hepatotoxicity and potential to progress to hepatic failure. Criteria for liver transplantation include the following:

-

Metabolic acidosis, persistent after fluid resuscitation

-

Kidney failure

-

Coagulopathy

-

Encephalopathy

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

A consensus statement on management of acetaminophen poisoning in the United States and Canada has been published. [3] See Guidelines.

See also the following:

For patient education information, see Tylenol Poisoning.

Background

Extensive medical use of acetaminophen began in 1947. Initially in the United States, acetaminophen was available by prescription only. In 1960, this changed to an over-the-counter (OTC) status. The availability of acetaminophen in OTC preparations and the contraindication of aspirin-containing products for pediatric use (due to the association between aspirin and Reye syndrome), have made acetaminophen one of the most commonly used analgesic-antipyretic medications in current pediatric medicine. This widespread use and availability also applies to the adult population, both in the United States and the rest of the world.

Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol (outside the United States and Canada) and by its chemical name, N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP), is available in more than 200 OTC and prescription medications, either as a single agent or in combination with other pharmaceuticals. Worldwide, acetaminophen is cited as a primary drug in over 50 brand- or trade-name products (eg, Tylenol, Panadol, Tempra, Mapap, FeverAll).

In the United States, 325-mg and 500-mg immediate-release tablets and a 650-mg extended-release preparation marketed for the treatment of arthritis are commonly sold. Combination formulations such as codeine-acetaminophen (Tylenol #3) and oxycodone-acetaminophen (Percocet) are prescribed. Numerous formulations and preparations are readily available, including the following:

-

Elixirs

-

Suspensions

-

Tablets (dissolvable [Tylenol Meltaways] and chewable)

-

Caplets

-

Capsules

-

Paraffin-base rectal suppositories (FeverAll)

Acetaminophen toxicity occurs relatively frequently. In fact, the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) reports that acetaminophen is one of the most common pharmaceuticals associated with both intentional and unintentional poisoning and toxicity. [4] Although acetaminophen has an excellent safety profile when administered in proper therapeutic doses, hepatotoxicity can occur with misuse and overdose. Recent studies in animal models and reports in humans have shown evidence that acetaminophen toxicity can adversely affect early neurodevelopment; however, the many safety studies of acetaminophen have been too short-term to be able to address this possibility. [5]

Overdose with acetaminophen can occur at any age. A therapeutic misadventure typically occurs in children younger than 1 year, when their caregivers give incorrect doses of a medication containing acetaminophen. Accidental poisoning (unintentional ingestion) can occur in toddlers and young children with unsupervised access to medications. Older patients (eg, teenagers and adults) may overdose with intent to do self-harm. [6]

While acetaminophen toxicity is particularly common in children, adults have accounted for most of the serious and fatal cases. [6] Acetaminophen toxicity is the most common cause of hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation in the United Kingdom. In the United States, acetaminophen toxicity has replaced viral hepatitis as the most common cause of acute hepatic failure and is the second most common cause of liver failure requiring transplantation.

In an attempt to decrease this potential for acetaminophen toxicity in the United States, a number of pharmaceutical regulatory changes have been introduced. In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required that nonprescription and prescription acetaminophen-containing medications provide information regarding the risks of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. In 2015, the FDA clarified the language of over-the-counter (OTC) warning labels for adults and children to read that severe liver damage may occur in any of the following circumstances [7] :

-

An adult takes more than 4,000 mg of acetaminophen in 24 hours.

-

A child takes more than 5 doses in 24 hours.

-

This product is taken with other drugs containing acetaminophen.

-

An adult has 3 or more alcoholic drinks every day while using this product.

In addition, the FDA has considered the removal of acetaminophen from some popular analgesic combination products (eg, hydrocodone-acetaminophen [Vicodin]) and possibly decreasing the recommended maximum daily dose. The FDA is also addressing other changes to acetaminophen-based medications, including the following:

-

Safe daily dose for healthy individuals (all ages: children and adults)

-

Safe daily dose for patients with chronic liver disease

-

Safe daily dose for patients who concurrently drink alcohol

-

Appropriate dose needed for efficacy

-

Package size restrictions

-

Current formulations of acetaminophen-narcotic combination drugs

In 2011, the FDA announced that it was asking manufacturers of prescription acetaminophen combination products to limit the maximum amount of APAP in these products to 325 mg per tablet, capsule, or other dosage unit. [8] In 2014, the FDA issued a statement advising that combination prescription pain relievers that contain more than 325 mg of acetaminophen per tablet, capsule, or other dosage unit should no longer be prescribed because of a risk for liver damage. [8, 9]

Analysis of cases from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), a large US hospitalization database, and the Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG), a cohort of 32 US medical centers, found that limiting the APAP content in combination products was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the yearly rate of hospitalizations and proportion per year of acute liver failure cases involving acetaminophen and opioid toxicity. The percentage of acute liver failure cases involving acetaminophen and opioid toxicity, which had increased 7% per year prior to the announcement, decreased 16% per year after the announcement (odds ratio 0.84; P < 0.001). [10]

Unrelated to dosage, another announcement from the FDA in 2013 advised that anyone who has a skin reaction, such as the development of a rash or blister, while taking acetaminophen should stop using the drug and seek immediate medical care. A review of the medical literature showed the painkiller poses the risk for three rare but potentially fatal skin disorders: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. [11, 12]

An intravenous (IV) formulation of acetaminophen (Ofirmev) was approved by the FDA in 2011 for inpatient use in children older than 2 years to treat fever and pain. [13] Although this article focuses on single acute ingestions of oral formulations, iatrogenic medication errors with IV acetaminophen have caused hepatotoxicity. [14] The evaluation and treatment approach for an IV acetaminophen overdose is similar to that of an oral overdose.

Clinical evidence of end-organ toxicity is often delayed 24-48 hours after an acute ingestion of acetaminophen. Consequently, the diagnosis of potential acetaminophen toxicity is based on obtaining a history of acetaminophen ingestion and confirming a potentially toxic blood level. The modified Rumack-Matthew nomogram (the acetaminophen toxicity nomogram or acetaminophen nomogram) is used to interpret plasma acetaminophen concentrations relative to time post ingestion to assess for the hepatotoxicity risk in patients. See Workup.

Oral activated charcoal avidly adsorbs acetaminophen. This gastrointestinal (GI) decontaminant can afford significant treatment benefit if administered to the patient within 1 hour post ingestion, or later if the ingestion involves an agent that delays gastric emptying or slows GI motility. N-acetylcysteine (NAC), or acetylcysteine, is an extremely effective antidote for acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity due to an acute overdose, especially if administered within 8-10 hours after ingestion. [15] See Treatment and Medication.

Pathophysiology

Ingested acetaminophen is rapidly absorbed from the stomach and small intestine. The serum concentration peaks 1-2 hours post ingestion. Therapeutic levels are 5-20 µg/mL (33-132 µmol/L). Peak plasma levels occur within 4 hours after ingestion of an overdose of an immediate-release preparation. Co-ingestion with drugs that delay gastric emptying (eg, opiates, anticholinergic agents) or ingestion of an acetaminophen extended-release formulation may result in peak serum levels being achieved more than 4 hours post ingestion.

Generally, the elimination half-life of acetaminophen is 2 hours (range 0.9-3.25 h). In patients with underlying liver dysfunction, the half-life can last as long as 17 hours post ingestion.

Acetaminophen is primarily metabolized by conjugation in the liver to nontoxic, water-soluble compounds that are eliminated in the urine. In acute overdose or when the maximum daily dose is exceeded over a prolonged period, metabolism by conjugation becomes saturated, and excess APAP is oxidatively metabolized by the CYP enzymes (CYP2E1, 1A2, 2A6, and 3A4) to the hepatotoxic reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI).

NAPQI has an extremely short half-life and is rapidly conjugated with glutathione, a sulfhydryl donor, and is then renally excreted. Under conditions of excessive NAPQI formation or a reduction in glutathione stores by approximately 70%, NAPQI covalently binds to the cysteinyl sulfhydryl groups of hepatocellular proteins, forming NAPQI-protein adducts. This causes an ensuing cascade of oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction. The subsequent inflammatory response propagates hepatocellular injury and death. Necrosis primarily occurs in the centrilobular (zone III) region, owing to the greater production of NAPQI by these cells.

Thus, the production of NAPQI, in excess of an adequate store of conjugating glutathione in the liver tissue, is associated with hepatocellular damage, necrosis, and hepatic failure. Similar enzymatic reactions occur in extrahepatic organs, such as the kidney, and can contribute to some degree of extrahepatic organ dysfunction

Currently, the maximum recommended daily dose of APAP is 75 mg/kg for children and 4 g for adults. The minimum hepatotoxic dose of APAP as a single acute ingestion is 150 mg/kg for a child and 7.5-10 g for an adult.

The ingested amount of APAP at which toxicity may occur may be less in the setting of chronic ethanol use, compromised nutritional states, fasting, or viral illness with dehydration. Co-ingestions of substances or medications known to induce the activity of the APAP-metabolizing cytochrome P (CYP) oxidative enzymes also increase the risk of hepatotoxicity; however, when proper dosing recommendations are followed, the risk of hepatotoxicity is extremely small.

The antidote for acetaminophen poisoning, NAC, is theorized to work through a number of protective mechanisms. Since NAC is a precursor of glutathione, it increases the concentration of glutathione available for the conjugation of NAPQI. NAC also enhances sulfate conjugation of unmetabolized APAP, functions as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant, and has positive inotropic effects.

In addition, NAC increases local nitric oxide concentrations and promotes microcirculatory blood flow, enhancing local oxygen delivery to peripheral tissues. The microvascular effects of NAC therapy are associated with a decrease in morbidity and mortality, even when NAC is administered in the setting of established hepatotoxicity.

NAC is maximally hepatoprotective when administered within 8 hours of an acute acetaminophen ingestion. When indicated, however, NAC should be administered regardless of the time since the overdose. Therapy with NAC has been shown to decrease mortality rates in late-presenting patients with fulminant hepatic failure, even in the absence of measurable serum APAP levels.

See the image below.

Etiology

Production of NAPQI by the CYP system in amounts greater than can be conjugated with existing stores of glutathione is the cause of liver toxicity in acetaminophen overdose. Susceptibility is enhanced by conditions that reduce glutathione stores in the body, which include the following:

-

Older age

-

Restricted diet

-

Underlying liver or kidney disease

-

Compromised nutritional status (eg, from prolonged fasting, eating disorders, cystic fibrosis, gastroenteritis, chronic alcoholism, or HIV disease)

In addition, the production of NAPQI (and thus the risk of hepatocellular injury) is increased by activation of the hepatic cytochrome system. Agents and medications that induce CYP enzyme activity are numerous, and include some of the following:

-

Ethanol ingestion

-

Tobacco smoking

-

Isoniazid (INH)

-

Rifampin

-

Phenytoin

-

Phenobarbital

-

Barbiturates

-

Carbamazepine

-

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ)

-

Zidovudine

Maximum acetaminophen dosages

Historically, the maximum daily adult dose of acetaminophen has been 4 g, with a recommended dosage of 352-650 mg every 4-6 hours or 1 g every 6 hours. In 2012, the FDA suggested, but did not mandate, a maximum daily dose for adults of 3 g, with no more than 650 mg every 6 hours, as needed. McNeil Consumer Healthcare, which produces the Tylenol brand of acetaminophen, has voluntarily reduced the maximum recommended daily adult dose of its 500 mg tablet product to 3 g and of its regular-strength 325 mg tablet to 3250 mg, [16]

For children younger than 12 years and/or less than 50 kg in weight, the maximum daily dose is 75 mg/kg, with a recommended dosage of 10-15 mg/kg every 4-6 hours as needed and no more than 5 doses per 24-hour period. Because of absorption differences, weight-based rectal suppository dosing for children is higher, at 15-20 mg/kg per dose, using the same time interval as for oral acetaminophen.

Minimum toxic acetaminophen dosages

In adults, the minimum toxic dose of acetaminophen for a single ingestion is 7.5-10 g. In children, the minimum toxic dose of APAP for a single acute ingestion is 150 mg/kg.

In healthy children aged 1-6 years, medical toxicologists recommend increasing this threshold to 200 mg/kg. Children in this age group are less susceptible to hepatotoxicity from acute acetaminophen poisoning. Differences in medication metabolism within this age group and a relatively larger hepatic mass (ie, ratio of organ weight to total body weight) may both play roles in more efficiently detoxifying and eliminating NAPQI.

Toxic acetaminophen dosages

In adults, an acute ingestion of more than 150 mg/kg or 12 g of acetaminophen is considered a toxic dose and poses a high risk of liver damage. In children, acute ingestion of 250 mg/kg or more poses significant risk for acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Children who ingest more than 350 mg/kg are at great risk for severe hepatotoxicity if not properly treated.

In 2009, the FDA announced requirements for nonprescription and prescription medications to provide new information regarding acetaminophen–induced hepatotoxicity. [17, 18, 19] The FDA addressed the possibility of removing acetaminophen from some popular analgesic combination products (eg, hydrocodone-acetaminophen [Vicodin]) and/or lowering the maximum cited daily dose of acetaminophen. The following concerns were also addressed:

-

Safe daily dose for healthy individuals (all ages: children and adults)

-

Safe daily dose for patients with chronic liver disease

-

Safe daily dose for patients who concurrently drink alcohol

-

Appropriate dose needed for efficacy

-

Package size restrictions

-

Current formulations of acetaminophen-narcotic combination drugs

In 2011, the FDA asked manufacturers of prescription acetaminophen combination products to limit the maximum amount of acetaminophen in these products to 325 mg per tablet, capsule, or other dosage unit.7 In 2014, the FDA issued a statement advising doctors to stop prescribing combination prescription pain relievers that contain more than 325 mg of acetaminophen per tablet, capsule, or other dosage unit. [8, 9]

In addition, in 2011 an industry-wide transition to one standard concentration of 160 mg/5 mL for all single-ingredient OTC pediatric liquid acetaminophen products was announced. Previously, mainly two concentrations of OTC acetaminophen formulations were available: 80 mg/0.8 mL (Infant Concentrated Drops) and 160 mg/5 mL (Children's Liquid Suspension or Syrup). The move to a single standard concentration was intended to minimize confusion of administration of acetaminophen preparations by caregivers, in the hope of reducing the occurrence of acetaminophen overdosing and decreasing the number of acute ingestions that cause hepatotoxicity leading to acute liver failure. [20]

Chronic acetaminophen toxicity

Chronic acetaminophen toxicity has been recognized in pediatric patients. This condition occurs in young, febrile children with reduced oral intake who are treated with repeated high doses of acetaminophen to relieve their symptoms. As a reference, the 24-hour dosage of acetaminophen for children should not exceed 75 mg/kg/d.

In chronic acetaminophen toxicity, the role of fasting, reduced glutathione stores, and enhanced metabolism remains unclear. Risk factors for chronic acetaminophen toxicity include the following [21] :

-

Repeated administration of high doses

-

Repeated administration of proper doses at shortened time intervals

-

Fever

-

Poor oral intake

-

Young age (as due to caregiver mismanagement)

Epidemiology

The American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System reported 66,710 single exposures to acetaminophen alone in 2022 (17,791 in pediatric patients, 32,911 in adults, and 16,008 in patients of unknown age), and 13,799 single exposures to acetaminophen in combination with other drugs. Acetaminophen exposure alone resulted in 167 deaths (81 in known adults; 1 in a known pediatric patient), and acetaminophen combinations resulted in 29 deaths. [4]

Acetaminophen toxicity is the most common cause of hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation in the United Kingdom. In the United States, acetaminophen toxicity has replaced viral hepatitis as the most common cause of acute hepatic failure and is the second most common cause of liver failure requiring transplantation. Although acetaminophen toxicity is particularly common in children, adults have accounted for most of the serious and fatal cases. [6]

Prognosis

With aggressive supportive care and antidotal therapy, the mortality rate associated with acetaminophen hepatotoxicity is less than 2%. If correctly treated in a timely manner, most patients do not suffer significant sequelae; patients who survive are expected to have return of normal liver function. In case series, fewer than 4% of patients who suffer severe hepatotoxicity develop liver failure, and less than half of them die or require liver transplantation.

Chronic ethanol use or diminished nutritional status may increase the risk for morbidity because these conditions result in deficient glutathione stores and a subsequent inability to conjugate and detoxify NAPQI. Use of substances that induce the activity of the APAP-metabolizing CYP enzymes may increase the risk of morbidity by enhancing the production of NAPQI (see Etiology).

Children younger than 6 years appear to fare better than adults after acute acetaminophen poisoning, perhaps owing to their greater capacity to conjugate APAP through sulfation, enhanced detoxification of NAPQI, or greater glutathione stores. However, as no controlled studies have supported an alternative pediatric-specific therapy, treatment in children is the same as in adults.

A number of screening measurements have been studied as prognostic indicators after acetaminophen ingestion. The most widely used predictors are the King’s College Criteria, which have been well-validated to predict poor outcome and need for liver transplantation after an isolated acetaminophen overdose. The criteria consist of the following laboratory abnormalities; any serologic or clinical finding should prompt urgent transplantation consultation:

-

Arterial pH less than 7.30 after fluid resuscitation

-

Creatinine level greater than 3.4 mg/dL

-

Prothrombin time (PT) greater than 1.8 times control or greater than 100 seconds, or International Normalized Ratio (INR) greater than 6.5

-

Grade III or IV encephalopathy

Levine et al reported that the combination of hypoglycemia, coagulopathy, and lactic acidosis performed better than the King's College criteria for predicting death or transplant. In their retrospective cohort study of 334 adult patients with a discharge diagnosis of acetaminophen-induced liver failure, the presence of hypoglycemia increased the odds of reaching the composite endpoint (death or transplantation) by 3.39-fold. For the combination of hypoglycemia, coagulopathy, and lactic acidosis, the pseudo R2 for the area under the curve was 0.93, versus 0.20 for the King's College criteria. [22]

Another prognostic screening tool that has been studied in regard to predicting the need for liver transplantation is the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score completed at the patient’s first inpatient hospital stay. In one study, the APACHE II score was found to be accurate, but cumbersome to apply. [23]

Additional early predictors include changes in serum phosphate levels, which indirectly represent the balance between the development of renal failure and hepatic regeneration. Serum phosphate concentrations greater than 1.2 mmol/L measured at 48-96 hours after overdose were sensitive and specific for increased mortality. [24]

Finally, elevations in blood lactate levels have been studied as prognostic indicators after acute acetaminophen overdose. [25] Blood lactate levels greater than 3.5 mmol/L before fluid resuscitation or greater than 3 mmol/L after fluid resuscitation were found to be sensitive and specific indicators of survival. When compared with the King’s College Criteria, there was no significant time difference to clearly identify patients who required transplantation.

Patient Education

Acetaminophen is commonly considered an innocuous OTC drug; hence, it is extremely important to advise patients of the potential risks associated with its inappropriate use. Inform parents and caregivers that acetaminophen, although safe when dosed properly, can cause significant harm if misused.

Educate parents in the proper dosing for children and the danger associated with misusing various acetaminophen preparations of different concentrations (eg, infant suspension vs pediatric elixir, pediatric vs adult suppositories). Currently, one standard concentration (160 mg/5 mL) of liquid acetaminophen medication is available for infants and children. Before 2011, OTC APAP formulations for infants and children were 80 mg/0.8 mL (Infant Concentrated Drops) and 160 mg/5 mL (Children's Liquid Suspension or Syrup). Despite the change to one standard formulation, the older concentrations (80 mg/0.8 mL) of infant acetaminophen may still be found in some homes. If an older APAP product is to be used, confirm the correct concentration of infant acetaminophen with the caregiver to prevent therapeutic error.

Parents should always be given clear instructions on dose and formulation, based on the age and weight of the child. Preferably, caregivers should use the dropper or syringe-measuring tool that accompanies the product. Parents must be instructed to carefully examine the labels of OTC medications that may contain acetaminophen in combination formulations.

Educate patients and caregivers about the increased potential for kidney toxicity associated with concurrent acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) analgesic use or with chronic ethanol use.

Parents and caregivers must ensure proper storage of medications within the home. This is critical in order to prevent unsupervised access to drugs or other toxic substances by children. The goal is to minimize the risk of an unintentional ingestion of a potentially toxic agent.

Supply parents and caregivers with contact information for their local Poison Control Center and the telephone number for the toll-free Poison Help Line (1-800-222-1222). In addition, McNeil pharmaceuticals (makers of the brand name “Tylenol” products) sponsors a toll-free number through the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, 1-800-525-6115, available 24 hours/d, for further consultation and guidance. [26]

For patient education information, see Tylenol Poisoning and Poison Proofing Your Home.

-

Semilogarithmic plot of plasma acetaminophen levels vs time. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Original_Nomogram_Rumack_BH_Matthew_H,_Acetaminophen_Pediatrics_1975_(55)_871_-_876.pdf).

-

Acetaminophen metabolism. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acetaminophen_metabolism.jpg).

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Approach Considerations

- Gastric Decontamination

- Oral N-Acetylcysteine

- Intravenous N-Acetylcysteine

- NAC and Activated Charcoal Interaction and Administration

- Delayed Presentation

- Chronic Ingestion

- Extended-Release Acetaminophen Overdose

- Fomepizole and Other Investigative Therapies

- Consultations

- Show All

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- References