Practice Essentials

Rotator cuff injuries are problems commonly encountered in athletic and nonathletic patients. Symptoms include pain, weakness, and decreased range of motion. Early diagnosis is important for identifying causes, implementing effective treatment, and preventing further injury. An emerging consensus suggests that the etiology of rotator cuff disease is multifactorial. Extrinsic factors exist, such as the morphology of the coracoacromial arch, tensile overload, repetitive use, and kinematics abnormalities. Intrinsic factors also exist, such as altered tendon vascular supply, microstructural collagen fiber abnormalities, and regional variations.

Pain or contracture may limit shoulder passive range of motion in patients with a rotator cuff tear, with mild or moderate limitations occurring in more than 40% of patients who have full-thickness tears. The most common causes are bursitis and synovitis due to the tear and frozen shoulde due to contracture of the soft tissues around the glenohumeral joint. [1]

Although pain management of this acute injury primarily consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), there is increasing evidence that a combination of acetaminophen and NSAIDs could offer superior analgesia. This could be considered as another option in the pain management of the acutely injured rotator cuff. [2, 3]

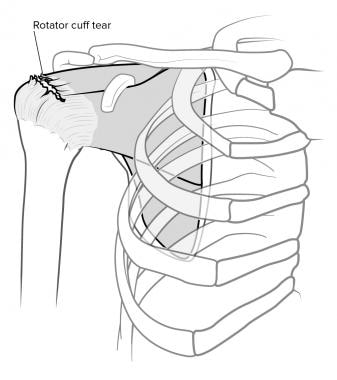

(A rotator cuff injury is shown in the image below.)

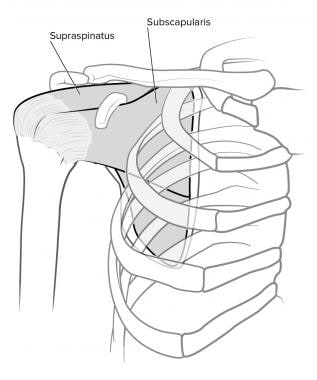

The rotator cuff muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. Repetitive microtrauma and anatomic variations lead to most rotator cuff injuries. Such injuries are commonly encountered in athletic and nonathletic patients. (See the image below.)

The precise incidence of symptomatic rotator cuff injuries is not known. Many individuals with full-thickness cuff tears are not only asymptomatic but they have minimal functional disability. The most accepted figure is 20-30%. Cadaver studies of elderly persons have estimated full-thickness tears as high as 30%. [4]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of rotator cuff injuries include the following:

-

Pain

-

Weakness

-

Decreased range of motion

-

Clicking

-

Catching

-

Stiffness

-

Crepitus

Diagnosis

Examination of a patient with suspected rotator cuff injuries includes a systematic approach to the shoulder, cervical spine, and upper extremity involving the following [5] :

-

Inspection: Look for any scars, color, edema, deformities, muscle atrophy, asymmetry.

-

Palpation of the bony and soft-tissue structures: Note any areas of tenderness.

-

Range of motion (active and passive): Note any pain elicited and loss of motion.

-

Strength testing: Compare bilaterally, and note any differences.

-

Neurologic assessment: Include the Neer impingement test to distinguish cuff disease from other sources of shoulder pain

-

Special shoulder tests.

Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears may be difficult to diagnose with a single imaging modality. Plain films are recommended for identification of other causes of shoulder pain, such as calcific tendinosis, osteoarthritis, or fracture. A high-riding humeral head (≤7 mm of acromiohumeral distance) may be identifiable on anteroposterior radiographs and suggests a large rotator cuff tear. MRI and ultrasonography have excellent diagnostic accuracy for full-thickness tears. [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

Radiologic studies that may be used to assess suspected rotator cuff injuries include the following:

-

Shoulder radiography: Anteroposterior, axillary, and lateral views; modified transscapular or supraspinatus outlet view.

-

Arthrography of the glenohumeral joint (advanced imaging): To diagnose rotator cuff disease. [12]

-

Ultrasonography (advanced imaging): To diagnose rotator cuff disease. [13]

Management

The goals of treatment for rotator cuff injuries are to reduce inflammation, relieve stress on the rotator cuff, and correct any biomechanical dysfunction. [3]

Patients with chronic injuries that have progressed to a rotator cuff tear may be treated conservatively with the following [2] :

-

Rest and activity modification

-

Shoulder sling

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

-

Corticosteroid injections

-

Basic shoulder-strengthening programs

If NSAIDs alone do not provide adequate pain relief, consider adding acetaminophen to the treatment regimen. [14] Other analgesics such as ibuprofen and ketoprofen may also be used in the management of rotator cuff injuries.

In most studies, injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for rotator cuff tendinopathy has not demonstrated significant clinical benefit as compared to other nonoperative treatments; however, PRP injection appears to improve rotator cuff tear healing and reduce early postoperative pain when used to augment surgical repair, though it does not significantly enhance postoperative shoulder function. [15]

Surgery

If patients have not improved by a 6-week assessment following conservative management, consider surgical therapy. Surgical therapy is indicated in the following patients:

-

Those younger than 60 years.

-

Those with a full-thickness tear demonstrated clinically or arthrographically.

-

Those who fail to improve after 6 weeks of rehabilitation.

-

Individuals performing activities that requires shoulder use.

Emergent orthopedic evaluation is warranted in acute injuries or even severe extension of chronic rotator cuff injuries, because they have a poor prognosis with conservative modalities.

In a retrospective study of 152 patients who underwent open repair of a posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tear, Ciampi and colleagues found that polypropylene patch augmentation of rotator cuff repair was associated with significantly better 3-year outcomes than was use of an absorbable collagen patch. [16, 17]

Epidemiology

An estimated 4% of cuff ruptures develop a cuff arthropathy. Various authors report a rate of success with conservative treatment ranging from 33-90%, with longer recovery time in older patients. Surgery results in improved function regardless of the patient's age. [18, 19, 20]

Rotator cuff injuries and tears usually do not occur in persons younger than 40 years (5-30%). The great majority is found in persons aged 55-85 years. Approximately 15% of patients with shoulder pain who are older than 70 years have rotator cuff injuries. [4]

-

Prevalence increases with age. [4]

-

Younger patients are more likely to have rotator cuff dysfunction because of overuse, subtle instability, and muscle imbalance.

-

Older patients tend to have chronic shoulder pain and degeneration.

Pathophysiology

Knowledge of the mechanical and normal anatomical structure allows for understanding of rotator cuff injuries (see Rotator Cuff Pathology). The rotator cuff muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor.

The subscapularis is a humeral head depressor and, in certain positions, an internal rotator. The infraspinatus and teres minor are external rotators. These muscles work as a unit, rather than individually, to maintain the dynamic glenohumeral stability. All are innervated by subscapular and axillary nerves. The vascular supply largely is dependent on the anterior humeral circumflex artery, which supplies the anterior cuff, and the posterior humeral circumflex and suprahumeral, which supply the posterior cuff.

Microscopically, all of the tendons of the rotator cuff fuse to form one continuous band, which is composed of a 5-layer structure. Because of this structure, none of the individual muscles have a higher incidence of tear, per se. However, the joint-side portion of the supraspinatus tendon is more susceptible to mechanical failure than the bursal side.

Most of the tears of the cuff are the result of chronic degeneration, which makes them susceptible to rupture. The chronic deterioration of the cuff results from the coracoacromial arch, which is composed of the bony acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, and the coracoid process. Because of its position above the rotator cuff, the coracoacromial arch forms the roof through which the supraspinatus tendon must pass (ie, supraspinatus outlet). Repetitive microtrauma and anatomic variations lead to most of the rotator cuff injuries.

Tendon degeneration is classified in 3 stages (classification of the impingement syndrome) based on the supraspinatus outlet.

-

Stage I - Edema and hemorrhage, affecting persons younger than 25 years

-

Stage II - Fibrosis and tendinitis, affecting persons aged 25-40 years

-

Stage III - Tears of cuff, affecting persons older than 50 years

Genetic factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff disease. A systematic review by Longo et al found significant associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms and rotator cuff disease for DEFB1, FGFR1, FGFR3, ESRRB, FGF10, MMP-1, TNC, FCRL3, SASH1, SAP30BP, and rs71404070 (located next to cadherin8). [21]

Prognosis

An estimated 4% of cuff ruptures develop a cuff arthropathy. [18] Various authors report the success rate of conservative treatment to be 33-90%, with longer recovery time required in older patients. [20] Surgery results in better function regardless of the patient's age.

Based on the Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index groupings, it appears that symptoms of pain are associated with emotions and lack of range of motion or stiffness, along with difficulty with daily activities. The symptom of "weakness” was associated with 2 very specific shoulder tasks: throwing hard and push-ups. [22]

In arthroscopic repair, massive and large tears tended to show a higher re-tearing when compared to medium tears. Repair showed improvement in functional outcomes when compared to preoperative findings. [23]

Navarro et al found that outpatient rotator cuff repair led to more unplanned ED and urgent care visits than other common outpatient orthopedic surgical procedures. Of 1306 outpatient rotator cuff repairs, 90 patients returned for ED or urgent care visits (6.9%). [24]

-

Rotator cuff, normal anatomy.

-

Rotator cuff tear, anterior view.

-

The acromioclavicular arch and the subacromial bursa.

-

Neer impingement test. The patient's arm is maximally elevated through forward flexion by the examiner, causing a jamming of the greater tuberosity against the anteroinferior acromion. Pain elicited with this maneuver indicates a positive test result for impingement.

-

Rotator cuff injury.

-

Normal intratendinous signal.

-

Partial-thickness tear seen better on angled oblique sagittal views.

-

Full-thickness tear.

-

Normal plain radiograph of the shoulder in internal, external, and neutral positions.