Practice Essentials

Appendicitis is defined as an inflammation of the inner lining of the vermiform appendix that spreads to its other parts. Despite diagnostic and therapeutic advancement in medicine, appendicitis remains a clinical emergency and is one of the more common causes of acute abdominal pain. See the image below.

Transverse graded compression transabdominal sonogram of an acutely inflamed appendix. Note the targetlike appearance due to thickened wall and surrounding loculated fluid collection.

Transverse graded compression transabdominal sonogram of an acutely inflamed appendix. Note the targetlike appearance due to thickened wall and surrounding loculated fluid collection.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of appendicitis is notoriously inconsistent. The classic history of anorexia and periumbilical pain followed by nausea, right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain, and vomiting occurs in only 50% of cases. Features include the following:

-

Abdominal pain: Most common symptom

-

Nausea: 61-92% of patients

-

Anorexia: 74-78% of patients

-

Vomiting: Nearly always follows the onset of pain; vomiting that precedes pain suggests intestinal obstruction

-

Diarrhea or constipation: As many as 18% of patients

Features of the abdominal pain are as follows:

-

Typically begins as periumbilical or epigastric pain, then migrates to the RLQ [1]

-

Patients usually lie down, flex their hips, and draw their knees up to reduce movements and to avoid worsening their pain

-

The duration of symptoms is less than 48 hours in approximately 80% of adults but tends to be longer in elderly persons and in those with perforation.

Physical examination findings include the following:

-

Rebound tenderness, pain on percussion, rigidity, and guarding: Most specific finding

-

RLQ tenderness: Present in 96% of patients, but nonspecific

-

Left lower quadrant (LLQ) tenderness: May be the major manifestation in patients with situs inversus or in patients with a lengthy appendix that extends into the LLQ

-

Male infants and children occasionally present with an inflamed hemiscrotum

-

In pregnant women, RLQ pain and tenderness dominate in the first trimester, but in the latter half of pregnancy, right upper quadrant (RUQ) or right flank pain may occur

The following accessory signs may be present in a minority of patients:

-

Rovsing sign (RLQ pain with palpation of the LLQ): Suggests peritoneal irritation

-

Obturator sign (RLQ pain with internal and external rotation of the flexed right hip): Suggests the inflamed appendix is located deep in the right hemipelvis

-

Psoas sign (RLQ pain with extension of the right hip or with flexion of the right hip against resistance): Suggests that an inflamed appendix is located along the course of the right psoas muscle

-

Dunphy sign (sharp pain in the RLQ elicited by a voluntary cough): Suggests localized peritonitis

-

RLQ pain in response to percussion of a remote quadrant of the abdomen or to firm percussion of the patient's heel: Suggests peritoneal inflammation

-

Markle sign (pain elicited in a certain area of the abdomen when the standing patient drops from standing on toes to the heels with a jarring landing): Has a sensitivity of 74% [2]

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The following laboratory tests do not have findings specific for appendicitis, but they may be helpful to confirm diagnosis in patients with an atypical presentation:

-

CBC

-

C-reactive protein (CRP)

-

Liver and pancreatic function tests

-

Urinalysis (for differentiating appendicitis from urinary tract conditions)

-

Urinary beta-hCG (for differentiating appendicitis from early ectopic pregnancy in women of childbearing age)

-

Urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA)

CBC

-

WBC >10,500 cells/µL: 80-85% of adults with appendicitis

-

Neutrophilia >75-78% of patients

-

Less than 4% of patients with appendicitis have a WBC count less than 10,500 cells/µL and neutrophilia less than 75%

In infants and elderly patients, a WBC count is especially unreliable because these patients may not mount a normal response to infection. In pregnant women, the physiologic leukocytosis renders the CBC count useless for the diagnosis of appendicitis.

C-reactive protein

-

CRP levels >1 mg/dL are common in patients with appendicitis

-

Very high levels of CRP in patients with appendicitis indicate gangrenous evolution of the disease, especially if it is associated with leukocytosis and neutrophilia

Urinary 5-HIAA

HIAA levels increase significantly in acute appendicitis and decrease when the inflammation shifts to necrosis of the appendix. [6] Therefore, such decrease could be an early warning sign of perforation of the appendix.

CT scanning

-

CT scanning with oral contrast medium or rectal Gastrografin enema has become the most important imaging study in the evaluation of patients with atypical presentations of appendicitis

-

Low-dose abdominal CT may be preferable for diagnosing children and young adults in whom exposure to CT radiation is of particular concern [7]

Ultrasonography

-

Ultrasonography may offer a safer alternative as a primary diagnostic tool for appendicitis, with CT scanning used in those cases in which ultrasonograms are negative or inconclusive

-

A healthy appendix usually cannot be viewed with ultrasonography; when appendicitis occurs, the ultrasonogram typically demonstrates a noncompressible tubular structure of 7-9 mm in diameter

-

Vaginal ultrasonography alone or in combination with transabdominal scan may be useful to determine the diagnosis in women of childbearing age [10]

Other imaging studies

-

Kidneys-ureters-bladder radiographs: Insensitive, nonspecific, and not cost-effective

-

Barium enema study: Has essentially no role in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis

-

Radionuclide scanning: Localized uptake of tracer in the RLQ suggests appendiceal inflammation

-

MRI: Useful in pregnant patients if graded compression ultrasonography is nondiagnostic

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Emergency department care is as follows:

-

Establish IV access and administer aggressive crystalloid therapy to patients with clinical signs of dehydration or septicemia

-

Keep patients with suspected appendicitis NPO

-

Administer parenteral analgesic and antiemetic as needed for patient comfort; no study has shown that analgesics adversely affect the accuracy of physical examination [11]

Appendectomy remains the only curative treatment of appendicitis, although nonoperative management is increasingly recognized as being safe and effective for uncomplicated cases of acute appendicitis. Management of patients with an appendiceal mass can usually be divided into the following 3 treatment categories:

-

Phlegmon or a small abscess: After IV antibiotic therapy, an interval appendectomy can be performed 4-6 weeks later

-

Larger well-defined abscess: After percutaneous drainage with IV antibiotics is performed, the patient can be discharged with the catheter in place; interval appendectomy can be performed after the fistula is closed

-

Multicompartmental abscess: These patients require early surgical drainage

Antibiotics

-

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered before every appendectomy

-

Preoperative antibiotics should be administered in conjunction with the surgical consultant

-

Broad-spectrum gram-negative and anaerobic coverage is indicated

-

Cefotetan and cefoxitin seem to be the best choices of antibiotics

-

In penicillin-allergic patients, carbapenems are a good option

-

Pregnant patients should receive pregnancy category A or B antibiotics

-

Antibiotic treatment may be stopped when the patient becomes afebrile and the WBC count normalizes

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Appendicitis is defined as an inflammation of the inner lining of the vermiform appendix that spreads to its other parts. This condition is a common and urgent surgical illness with protean manifestations, generous overlap with other clinical syndromes, and significant morbidity, which increases with diagnostic delay (see Presentation). In fact, despite diagnostic and therapeutic advancement in medicine, appendicitis remains a clinical emergency and is one of the more common causes of acute abdominal pain.

No single sign, symptom, or diagnostic test accurately confirms the diagnosis of appendiceal inflammation in all cases, and the classic history of anorexia and periumbilical pain followed by nausea, right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain, and vomiting occurs in only 50% of cases (see Presentation).

Appendicitis may occur for several reasons, such as an infection of the appendix, but the most important factor is the obstruction of the appendiceal lumen (see Pathophysiology and Etiology). Left untreated, appendicitis has the potential for severe complications, including perforation or sepsis, and may even cause death (see Prognosis). However, the differential diagnosis of appendicitis is often a clinical challenge because appendicitis can mimic several abdominal conditions (see Diagnostic Considerations). [12]

Appendectomy remains the only curative treatment of appendicitis (see Treatment). The surgeon's goals are to evaluate a relatively small population of patients referred for suspected appendicitis and to minimize the negative appendectomy rate without increasing the incidence of perforation. The emergency department (ED) clinician must evaluate the larger group of patients who present to the ED with abdominal pain of all etiologies with the goal of approaching 100% sensitivity for the diagnosis in a time-, cost-, and consultation-efficient manner.

Go to Pediatric Appendicitis for more information on this topic.

Anatomy

The appendix is a wormlike extension of the cecum and, for this reason, has been called the vermiform appendix. The average length of the appendix is 8-10 cm (ranging from 2-20 cm). The appendix appears during the fifth month of gestation, and several lymphoid follicles are scattered in its mucosa. Such follicles increase in number when individuals are aged 8-20 years. A normal appendix is seen below.

Normal appendix; barium enema radiographic examination. A complete contrast-filled appendix is observed (arrows), which effectively excludes the diagnosis of appendicitis.

Normal appendix; barium enema radiographic examination. A complete contrast-filled appendix is observed (arrows), which effectively excludes the diagnosis of appendicitis.

The appendix is contained within the visceral peritoneum that forms the serosa, and its exterior layer is longitudinal and derived from the taenia coli; the deeper, interior muscle layer is circular. Beneath these layers lies the submucosal layer, which contains lymphoepithelial tissue. The mucosa consists of columnar epithelium with few glandular elements and neuroendocrine argentaffin cells.

Taenia coli converge on the posteromedial area of the cecum, which is the site of the appendiceal base. The appendix runs into a serosal sheet of the peritoneum called the mesoappendix, within which courses the appendicular artery, which is derived from the ileocolic artery. Sometimes, an accessory appendicular artery (deriving from the posterior cecal artery) may be found.

Appendiceal vasculature

The vasculature of the appendix must be addressed to avoid intraoperative hemorrhages. The appendicular artery is contained within the mesenteric fold that arises from a peritoneal extension from the terminal ileum to the medial aspect of the cecum and appendix; it is a terminal branch of the ileocolic artery and runs adjacent to the appendicular wall. Venous drainage is via the ileocolic veins and the right colic vein into the portal vein; lymphatic drainage occurs via the ileocolic nodes along the course of the superior mesenteric artery to the celiac nodes and cisterna chyli.

Appendiceal location

The appendix has no fixed position. It originates 1.7-2.5 cm below the terminal ileum, either in a dorsomedial location (most common) from the cecal fundus, directly beside the ileal orifice, or as a funnel-shaped opening (2-3% of patients). The appendix has a retroperitoneal location in 65% of patients and may descend into the iliac fossa in 31%. In fact, many individuals may have an appendix located in the retroperitoneal space; in the pelvis; or behind the terminal ileum, cecum, ascending colon, or liver. Thus, the course of the appendix, the position of its tip, and the difference in appendiceal position considerably changes clinical findings, accounting for the nonspecific signs and symptoms of appendicitis.

Congenital appendiceal disorders

Appendiceal congenital disorders are extremely rare but occasionally reported (eg, agenesis, duplication, triplication).

Pathophysiology

Reportedly, appendicitis is caused by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen from a variety of causes (see Etiology). Independent of the etiology, obstruction is believed to cause an increase in pressure within the lumen. Such an increase is related to continuous secretion of fluids and mucus from the mucosa and the stagnation of this material. At the same time, intestinal bacteria within the appendix multiply, leading to the recruitment of white blood cells (see the image below) and the formation of pus and subsequent higher intraluminal pressure.

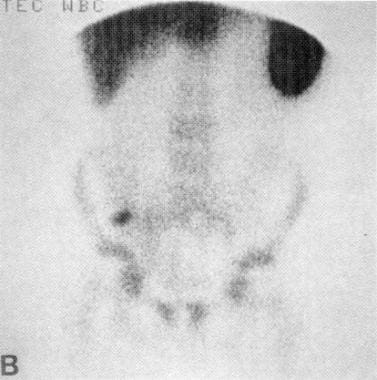

Technetium-99m radionuclide scan of the abdomen shows focal uptake of labeled WBCs in the right lower quadrant consistent with acute appendicitis.

Technetium-99m radionuclide scan of the abdomen shows focal uptake of labeled WBCs in the right lower quadrant consistent with acute appendicitis.

If appendiceal obstruction persists, intraluminal pressure rises ultimately above that of the appendiceal veins, leading to venous outflow obstruction. As a consequence, appendiceal wall ischemia begins, resulting in a loss of epithelial integrity and allowing bacterial invasion of the appendiceal wall.

Within a few hours, this localized condition may worsen because of thrombosis of the appendicular artery and veins, leading to perforation and gangrene of the appendix. As this process continues, a periappendicular abscess or peritonitis may occur.

Etiology

Appendicitis is caused by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen. The most common causes of luminal obstruction include lymphoid hyperplasia secondary to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or infections (more common during childhood and in young adults), fecal stasis and fecaliths (more common in elderly patients), parasites (especially in Eastern countries), or, more rarely, foreign bodies and neoplasms.

Fecaliths form when calcium salts and fecal debris become layered around a nidus of inspissated fecal material located within the appendix. Lymphoid hyperplasia is associated with various inflammatory and infectious disorders including Crohn disease, gastroenteritis, amebiasis, respiratory infections, measles, and mononucleosis.

Obstruction of the appendiceal lumen has less commonly been associated with bacteria (Yersinia species, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, actinomycosis, Mycobacteria species, Histoplasma species), parasites (eg, Schistosomes species, pinworms, Strongyloides stercoralis), foreign material (eg, shotgun pellet, intrauterine device, tongue stud, activated charcoal), tuberculosis, and tumors.

Epidemiology

Appendicitis is one of the more common surgical emergencies, and it is one of the most common causes of abdominal pain. In the United States, 250,000 cases of appendicitis are reported annually, representing 1 million patient-days of admission. The incidence of acute appendicitis has been declining steadily since the late 1940s, and the current annual incidence is 10 cases per 100,000 population. Appendicitis occurs in 7% of the US population, with an incidence of 1.1 cases per 1000 people per year. Some familial predisposition exists.

In Asian and African countries, the incidence of acute appendicitis is probably lower because of the dietary habits of the inhabitants of these geographic areas. The incidence of appendicitis is lower in cultures with a higher intake of dietary fiber. Dietary fiber is thought to decrease the viscosity of feces, decrease bowel transit time, and discourage formation of fecaliths, which predispose individuals to obstructions of the appendiceal lumen.

In the last few years, a decrease in frequency of appendicitis in Western countries has been reported, which may be related to changes in dietary fiber intake. In fact, the higher incidence of appendicitis is believed to be related to poor fiber intake in such countries.

There is a slight male preponderance of 3:2 in teenagers and young adults; in adults, the incidence of appendicitis is approximately 1.4 times greater in men than in women. The incidence of primary appendectomy is approximately equal in both sexes.

The incidence of appendicitis gradually rises from birth, peaks in the late teen years, and gradually declines in the geriatric years. The mean age when appendicitis occurs in the pediatric population is 6-10 years. Lymphoid hyperplasia is observed more often among infants and adults and is responsible for the increased incidence of appendicitis in these age groups. Younger children have a higher rate of perforation, with reported rates of 50-85%. The median age at appendectomy is 22 years. Although rare, neonatal and even prenatal appendicitis have been reported. Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion in all age groups.

Go to Pediatric Appendicitis for more information on this topic.

Prognosis

Acute appendicitis is the most common reason for emergency abdominal surgery. Appendectomy carries a complication rate of 4-15%, as well as associated costs and the discomfort of hospitalization and surgery. Therefore, the goal of the surgeon is to make an accurate diagnosis as early as possible. Delayed diagnosis and treatment account for much of the mortality and morbidity associated with appendicitis.

The overall mortality rate of 0.2-0.8% is attributable to complications of the disease rather than to surgical intervention. The mortality rate in children ranges from 0.1% to 1%; in patients older than 70 years, the rate rises above 20%, primarily because of diagnostic and therapeutic delay.

Appendiceal perforation is associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared with nonperforating appendicitis. The mortality risk of acute but not gangrenous appendicitis is less than 0.1%, but the risk rises to 0.6% in gangrenous appendicitis. The rate of perforation varies from 16% to 40%, with a higher frequency occurring in younger age groups (40-57%) and in patients older than 50 years (55-70%), in whom misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis are common. Complications occur in 1-5% of patients with appendicitis, and postoperative wound infections account for almost one third of the associated morbidity.

In a multivariable analysis, independent factors predictive of complicated appendicitis in children were as follows [13] :

-

Age younger than 5 years

-

Symptom duration longer than 24 hours

-

Hyponatremia

-

Leukocytosis

-

CT scan reveals an enlarged appendix with thickened walls, which do not fill with colonic contrast agent, lying adjacent to the right psoas muscle.

-

Sagittal graded compression transabdominal sonogram shows an acutely inflamed appendix. The tubular structure is noncompressible, lacks peristalsis, and measures greater than 6 mm in diameter. A thin rim of periappendiceal fluid is present.

-

Transverse graded compression transabdominal sonogram of an acutely inflamed appendix. Note the targetlike appearance due to thickened wall and surrounding loculated fluid collection.

-

Technetium-99m radionuclide scan of the abdomen shows focal uptake of labeled WBCs in the right lower quadrant consistent with acute appendicitis.

-

Perforated appendicitis.

-

Normal appendix; barium enema radiographic examination. A complete contrast-filled appendix is observed (arrows), which effectively excludes the diagnosis of appendicitis.