Practice Essentials

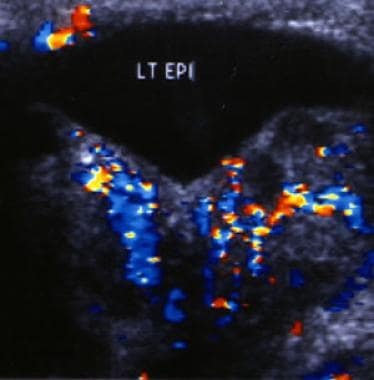

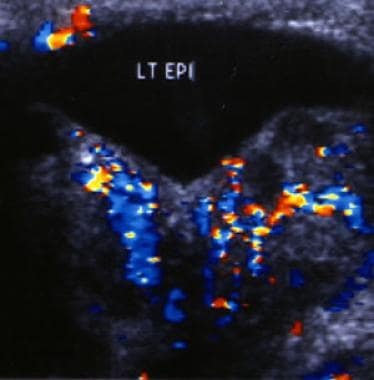

The epididymis is a coiled, tubular structure located along the posterior aspect of the testis. It allows for storage, maturation, and transport of sperm, connecting the efferent ducts of the testis to the vas deferens. Inflammation of the epididymis can be acute (< 6 wk) or chronic and is most commonly caused by infection. [1, 2, 3, 4] An example of active inflammation of the epididymis is seen in the image below.

Most cases of epididymitis occur in males aged 20 to 39 years, and most cases are associated with a sexually transmitted disease. After 39 years of age, the most common causes are Escherichia coli and other coliform bacteria. In the United States, more than 600,000 men are affected annually. Reflux of urine into the ejaculatory ducts has been reported to be the most common cause of epididymitis in children younger than 14 years. [3, 4, 33]

Acute infective epididymitis is the most common cause of scrotal pain in adults. The severe course of the disease requires immediate antimicrobial management, antibiotic treatment, and supportive measures. Patients with chronic indwelling catheters who develop epididymitis show a more severe clinical course compared to patients without a catheter. [5]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), acute epididymitis consists of pain, swelling, and inflammation of the epididymis lasting less than 6 weeks. If the testis is involved, the condition is called epididymo-orchitis. In sexually active men older than 35 years, the most common causes are Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. [1, 6]

The CDC recommends that the following tests and findings be used to help diagnose acute epididymitis [32, 6] :

-

Gram or methylene blue or gentian violet stain of urethral secretions demonstrating ≥2 white blood cells (WBCs) per oil immersion field

-

Positive leukocyte esterase testing on first-void urine

-

Microscopic examination of sediment from a spun first-void urine demonstrating ≥10 WBCs per high-power field

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.

One must have a high index of suspicion for testicular torsion. Ultrasonography can help differentiate epididymitis from testicular torsion. [7, 8]

In a study of 237 patients with acute epididymitis, a causative pathogen was identified in 132 antibiotic-naive patients and in 44 pretreated patients. The primary pathogen was E coli. Sexually transmitted infections were present in 34 cases (25 patients with C trachomatis). [9]

In prepubertal boys, a viral infection may be the most likely explanation, according to a British study. The authors note that management should be supportive and antibiotics reserved for patients with pyuria or positive cultures. Urodynamic studies and renal tract ultrasonography are suggested for those with recurrent epididymitis. [10]

Tumors, segmental testicular infarction, testicular vasculitis, pancreatitis, brucellosis, spermatic vein thrombosis, acute aortic syndrome, and appendicitis have all been identified as rare underlying causes of acute scrotal pain. [30]

Treatment

Acute epididymitis is treated with antibiotic therapy, analgesics for pain control, and supportive care, which includes scrotal elevation and support, application of an ice pack, and, in some cases, spermatic cord block. Most cases of acute epididymitis are caused by bacterial infection, most often by sexually transmitted organisms and urinary pathogens. Current treatment regimens remain empirical, although advances using modern diagnostic techniques support a change in the management paradigm. [11]

For sexually active males 14-35 years of age, a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone with 10 days of oral doxycycline is the recommended treatment. For men who have anal intercourse, ceftriaxone with 10 days of oral levofloxacin or ofloxacin is recommended. In men older than 35 years, epididymitis is usually caused by enteric bacteria in the ejaculatory ducts caused by reflux of urine secondary to bladder outlet obstruction. In such cases, levofloxacin or ofloxacin is ordinarily used to treat infection. [3]

According to the CDC, for acute epididymitis that is most likely caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea, provide ceftriaxone 500 mg IM in a single dose (1 g ceftriaxone for persons ≥150 kg), plus doxycycline 100 mg orally 2 times a day for 10 days. For acute epididymitis that is most likely caused by chlamydia, gonorrhea, or enteric organisms (men who practice insertive anal sex), provide ceftriaxone 500 mg IM in a single dose (1 g ceftriaxone for persons ≥150 kg), plus levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily for 10 days. For acute epididymitis that is most likely caused by enteric organisms only, prescribe levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily for 10 days. [32]

The CDC also notes that levofloxacin monotherapy should be considered if the infection is most likely caused by enteric organisms only and if gonorrhea has been ruled out by Gram, methylene blue, or gentian violet stain. This includes men who have undergone prostate biopsy, vasectomy, and other urinary tract instrumentation procedures. [32]

The choice of the initial antibiotic regimen is empirical and is based on the most likely causative pathogen, whether sexually transmitted, enteric, or other. Advanced microbiology techniques and studies of modern practice have provided new insights that have challenged traditional management paradigms. Much of the currently available guidance is derived from previous guidance recommendations, knowledge of antimicrobial activities of specific agents, and treatment outcomes in patients with uncomplicated infections. [11, 31]

Consult a urologist immediately if torsion is a possibility. Testicular torsion is a clinical diagnosis, and consultation should not be delayed for performance of additional ancillary studies. Otherwise, most cases of epididymitis can be managed on an outpatient basis, and follow-up with a urologist can be scheduled within 3-7 days. All pediatric cases of epididymitis require immediate consultation because of the high incidence of associated genitourinary anomalies. [12, 13, 14, 15]

Differentiation of Epididymitis From Testicular Torsion

Acute scrotal pain is a common presenting symptom in the emergency department. One must have a high index of suspicion for testicular torsion, a true scrotal emergency, when evaluating patients with acute testicular or scrotal pain. [2, 16]

The most common misdiagnosis for testicular torsion is epididymitis. Often, this results from reliance on imperfect diagnostic tests over clinical judgment. Surgical exploration to definitively exclude torsion is not a high-risk procedure. Insist on rapid, in-person consultation by the urologist in suspect cases.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is noninvasive and can help to differentiate epididymitis from testicular torsion. [7, 8] (The ultrasonogram below reveals the presence of epididymitis.) One topic of study is the ability of emergency physicians to use bedside ultrasonography to accurately diagnose acute scrotal pain.

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.

In a retrospective chart review of 36 patients with a chief complaint of acute scrotal pain who were evaluated by an emergency physician (EP) with the aid of bedside ultrasonography, ultrasonographic findings were consistent with the results of confirmatory studies (radiology or surgery) in 35 of 36 patients. Bedside ultrasonography had a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 94%. [17]

In a study of 134 adult patients with acute epididymitis who underwent scrotal ultrasonography and palpation on first presentation, epididymitis was predominantly located in 24 cases (17.9%) in the head, 52 cases (38.8%) in the tail, and 58 cases (43.3%) in both. Common ultrasound features included hydrocele, epididymal enlargement, hyperperfusion, and testicular involvement. Under conservative treatment, ultrasound parameters normalized without evidence of testicular atrophy, even in patients with epididymal abscess or concomitant orchitis. [18]

However, although the use of bedside ultrasonography to accurately diagnose acute scrotal pain is promising, the skill level of EPs in using ultrasonography varies, and larger randomized, prospective, blinded studies are needed to further evaluate the accuracy of these study results.

Boettcher et al. performed a retrospective study to differentiate torsion of the appendix testis (AT) from epididymitis and found that the best predictors for epididymitis were dysuria, a painful epididymis on palpation, and altered epididymal echogenicity and increased peritesticular perfusion noted on ultrasound studies. For torsion of the AT, the best predictor was a positive blue dot sign (a tender nodule with blue discoloration on the upper pole of the testis). [19]

CRP and ESR

A study by Asgari et al suggests that C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be useful in differentiating epididymitis from testicular torsion. In this prospective study, investigators evaluated 120 patients with the diagnosis of acute scrotum; serum CRP and ESR were drawn at the time of admission. Of 46 patients with diagnosed epididymitis, 44 (95.6%) had elevation in CRP levels, and among 23 patients with torsion, 1 (4%) had an elevated CRP level. Of the 51 additional patients with other noninflammatory causes of acute scrotum, none had significant elevation in CRP levels. In addition, ESR was highest in the epididymitis group. Study authors proposed cutoff values for distinguishing epididymitis from noninflammatory causes of acute scrotum of 24 mg/L for CRP and 15.5 mm/hr for ESR. [20]

Medical Care

Emergency department

Patients with testicular or scrotal pain require immediate evaluation to identify and quickly treat potential cases of testicular torsion. Although most cases of torsion occur in patients aged 12-18 years, testicular torsion should be considered in any patient aged 12-30 years who presents with scrotal pain. Immediate urologic consultation should be obtained if testicular torsion cannot be clearly differentiated from epididymitis or other scrotal pathology.

In a 21-year retrospective study of 252 pediatric patients with diagnosed epididymitis or epididymo-orchitis, age at first presentation was 10.92 ± 4.08 years. Most cases occurred during the pubertal period (11-14 years), and few patients younger than 2 years had diagnosed epididymitis (4%). A total of 69 boys (27.4%) experienced a second episode of epididymitis. Scrotal ultrasound results were consistent with epididymitis in 87.3% of cases (144/165). [21]

Acute epididymitis is treated with antibiotic therapy, analgesics for pain control, and supportive care, which includes scrotal elevation and support, application of an ice pack, and, in some cases, spermatic cord block.

Inpatient care

Most cases of epididymitis can be managed on an outpatient basis. However, the patient should be admitted for parenteral therapy if any of the following are present:

-

Intractable pain

-

Nausea or vomiting that interferes with oral therapy

-

Clinical evidence of an abscess (or inability to rule out an abscess)

-

Signs of toxicity or possible sepsis

-

Failure to improve during initial 72 hours of outpatient management

-

Immunocompromised with significant signs or symptoms

Outpatient care

Treatment should be initiated as discussed above.

The patient must be evaluated by a urologist within 3-7 days of presentation. This follow-up is mandatory, as a testicular tumor occasionally is the true cause of symptoms.

The patient must receive detailed instructions for treatment, including reasons for immediate return.

Patients with epididymitis secondary to a potential sexually transmitted disease along with all of their sexual contacts need referrals for screening and diagnosis of all comorbid sexually transmitted diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

For pediatric patients with no prior urologic history and in the absence of bacteriuria, one retrospective study suggests that investigation for underlying urinary tract pathology should be carried out after the second episode. [22]

Medications

In general, antibiotics should be used in all cases of epididymitis, regardless of a negative urinalysis or the urethral Gram stain result. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or narcotic analgesics are also generally prescribed for patients with epididymitis.

However, in one study of epididymitis in 140 boys aged 2 months to 17 years (median age, 11 yr), only 5 of 140 patients had a proven bacterial infection. Given this low rate of a bacterial cause, study authors recommend a selective approach to antibiotic therapy in pediatric epididymitis. They suggest treating all young infants, regardless of urinalysis results, and older boys who have a positive urinalysis or culture. They also recommend presumptive treatment of sexually active adolescents with epididymitis for sexually transmitted infection. This study excluded boys with recent urologic surgery and known lower urinary tract anomalies. [23]

Antibiotics

Empiric coverage varies with patient age and sexual history. Medications include ceftriaxone, doxycycline, levofloxacin, and ofloxacin. [3, 6, 9, 15, 24, 25]

Prepubertal patients and older men require empirical coverage for coliform bacteria (enteric gram-negative bacilli or Pseudomonas). Both of these patient populations may be treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Sexually active men need empirical coverage for C trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, usually with ceftriaxone and doxycycline or azithromycin. [26]

Fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for treatment of gonorrhea in the United States. This change is based on an analysis of data from the CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP). Data from GISP show an 11-fold increase in the proportion of fluoroquinolone-resistant gonorrhea (QRNG) among heterosexual men. [27] This limits treatment of gonorrhea to drugs in the cephalosporin class. Fluoroquinolones may serve as an alternative treatment option for patients with disseminated gonococcal infection if antimicrobial susceptibility can be documented.

Questions & Answers

Overview

What are the CDC diagnostic guidelines for acute epididymitis?

How is testicular torsion differentiated from acute epididymitis?

What causes acute epididymitis?

How is acute epididymitis treated?

Which specialist consultations are beneficial to patients with acute epididymitis?

What is the role of surgical exploration in the diagnosis of acute epididymitis?

What is the role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of acute epididymitis?

What is the role of lab testing in the diagnosis of acute epididymitis?

What is the role of antibiotics in the treatment of acute epididymitis?

When is inpatient care indicated for the treatment for acute epididymitis?

What is included in emergency department (ED) care of acute epididymitis?

-

Color Doppler sonogram of the left epididymis in a patient with acute epididymitis. The image demonstrates increased blood flow in the epididymis resulting from the active inflammation.