Practice Essentials

Suprascapular neuropathy is a less common cause of shoulder pain in athletes but is seen particularly in those who participate in overhead activities. Athletes who participate regularly in overhead sports are more susceptible to developing suprascapular neuropathy. Sports such as baseball, volleyball, and tennis demand skills that place substantial load on the athlete’s shoulder when the upper limb is in an overhead or abducted and externally rotated position (see image below). [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]

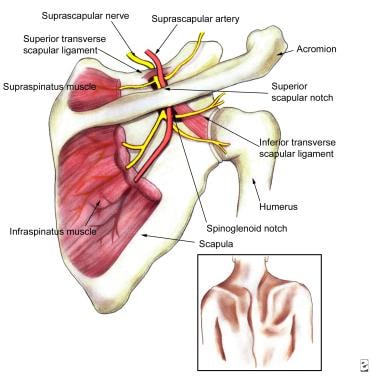

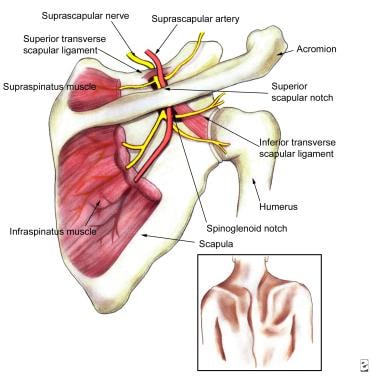

Clinically relevant anatomy of the suprascapular nerve (SSN) and the structures it innervates. The SSN is vulnerable to entrapment at the superior scapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch, beneath the inferior transverse scapular ligament. The inset depicts the clinical appearance in an individual with predominantly right-sided atrophy of the infraspinatus muscle due to suprascapular neuropathy.

Clinically relevant anatomy of the suprascapular nerve (SSN) and the structures it innervates. The SSN is vulnerable to entrapment at the superior scapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch, beneath the inferior transverse scapular ligament. The inset depicts the clinical appearance in an individual with predominantly right-sided atrophy of the infraspinatus muscle due to suprascapular neuropathy.

Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that athletes who participate in these and other overhead sports are at higher risk for overuse injuries of the shoulder in particular, including rotator cuff tendinopathy and injuries to the glenoid labrum. [6, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26] Suprascapular neuropathy has been reported to cause 1-2% of all shoulder pain [27] and is therefore often overlooked. However, the prevalence in higher risk athletic populations, such as volleyball players, has been reported to be as high as 33%. [27] Therefore, suprascapular neuropathy should be considered when evaluating shoulder pain in an overhead athlete.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Although the true incidence is unknown, several authors believe that suprascapular neuropathy is underreported. Suprascapular neuropathy was thought to be a diagnosis of exclusion given the similar clinical presentation as glenohumeral joint and rotator cuff pathology. However, increasing awareness and improvement in diagnostic modalities has resulted in increasing diagnosis. [27, 28] The condition has been described in various athletes, including weight lifters and baseball players, although the prevalence of suprascapular neuropathy appears to be highest among volleyball players. [1, 4, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21, 29, 30, 31] It occurs primarily in persons aged younger than 40 years. [32]

Studies have reported that 13-33% of elite volleyball athletes have signs of suprascapular neuropathy. [27, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 31] This observation lends credence to the term “volleyball shoulder.”

In addition to overhead athletes, some other higher risk populations for suprascapular neuropathy include patients with massive rotator cuff tears resulting in fatty infiltration of the muscle. Patients with posterior labral tears resulting in paralabral cysts that can compress the nerve are also a higher risk population. [27]

Functional Anatomy

The suprascapular nerve (SSN) is a mixed nerve that provides the motor innervation of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles and the sensory and proprioceptive innervation of the posterior aspect of the glenohumeral joint, as well as the acromioclavicular joint, subacromial bursa, and scapula. [33, 34, 35, 36] This nerve carries afferents from approximately 70% of the shoulder joint. The nerve arises from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus and is composed predominantly of C5-C6 level fibers. Some authors suggest that the nerve may also receive contributions from the fourth cervical nerve root in as many as 25% of people. Although the suprascapular nerve is a mixed nerve, it typically carries no cutaneous afferent fibers. The SSN is thought to carry cutaneous afferent fibers in only 15-25% of the general population.

In its initial course, the SSN courses posterior and parallel to the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle and anterior to the trapezius muscle in the posterior triangle of the neck. The nerve then passes dorsally through the suprascapular notch, where it is retained by the transverse scapular ligament, into the suprascapular fossa, where 2 motor branches to the supraspinatus muscle originate. Just proximal to the suprascapular notch, the SSN gives off the superior articular branch, which travels with its fellow nerve through the notch before proceeding laterally to innervate the acromioclavicular joint and its associated bursa and the coracoclavicular and coracohumeral ligaments (see below).

Clinically relevant anatomy of the suprascapular nerve (SSN) and the structures it innervates. The SSN is vulnerable to entrapment at the superior scapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch, beneath the inferior transverse scapular ligament. The inset depicts the clinical appearance in an individual with predominantly right-sided atrophy of the infraspinatus muscle due to suprascapular neuropathy.

Clinically relevant anatomy of the suprascapular nerve (SSN) and the structures it innervates. The SSN is vulnerable to entrapment at the superior scapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch, beneath the inferior transverse scapular ligament. The inset depicts the clinical appearance in an individual with predominantly right-sided atrophy of the infraspinatus muscle due to suprascapular neuropathy.

Cadaveric studies reveal that the suprascapular notch may be either U -shaped or V -shaped, and some physicians believe that this anatomic variation may be related to an individual’s predisposition to SSN entrapment at this level. After supplying the supraspinatus, the nerve subsequently travels inferolaterally to wrap around the spine of the scapula at the spinoglenoid notch.

In roughly 15-80% of cadavers studied, the spinoglenoid (inferior transverse scapular) ligament traverses this notch, creating a tunnel through which the nerve travels. Interestingly, the spinoglenoid ligament is reportedly more common in males than in females; this observation may provide an anatomic basis for any possible sex-related predominance in the prevalence of volleyball shoulder. The inferior articular branch, which contains afferents from the posterior glenohumeral joint capsule, joins the suprascapular nerve at the level of the spine of the scapula. After exiting the fibro-osseous tunnel at the spinoglenoid notch the nerve turns inferomedially before arborizing into 3 or 4 terminal branches that supply the infraspinatus muscle.

Sport-Specific Biomechanics

Suprascapular nerve entrapment or injury can occur at the suprascapular notch or the spinoglenoid notch. The resulting clinical presentation depends on the location of the suprascapular neuropathy. Selective involvement of the suprascapular nerve at the spinoglenoid notch level results in the isolated atrophy and weakness of the infraspinatus muscle that has been described as an infraspinatus syndrome. The available literature suggests that the most common site of entrapment among volleyball athletes is the spinoglenoid notch. [12, 37]

Several mechanisms have been proposed for suprascapular neuropathy. These mechanisms include repeat traction and microtrauma, direct compression of the nerve by surrounding normal anatomy or compression by pathologic space occupying lesions, and ischemia of the nerve from repetitive trauma. However, general agreement is that the suprascapular nerve may be vulnerable to injury due to compressive forces or repetitive distraction.

One mechanism is a traction injury that overhead athletes can be susceptible to, given the great amount of motion at the shoulder. The importance of the scapula in the throwing motion and other overhead sport-specific skills is now well appreciated. As the scapula protracts and retracts with functional use of the upper limb, some traction of the suprascapular nerve can be expected to occur at one or both notches through which it traverses. This concept forms the basis of the “sling effect," which proposes that, in certain functional positions of the upper limb, the suprascapular nerve is exposed to damaging sheer stress in the suprascapular notch. Similar reasoning leads to the prediction that the nerve is vulnerable to traction injury as it bends around the spine of the scapula at the spinoglenoid notch.

Some authors have proposed that individuals in whom the suprascapular nerve angles sharply around the spinoglenoid notch may be particularly prone to this mechanism of injury. The so-called "SICK scapula" (defined by Burkhart et al as scapular protraction, inferior border prominence, coracoid tightness, and scapular dyskinesis) that occurs in adaptive response to chronic shoulder overuse and functional instability may also theoretically contribute to the increased tension on the suprascapular nerve via the sling effect. [6]

Demirhan et al reported that the spinoglenoid ligament, when present, inserts into the posterior glenohumeral capsule. [38] They also observed that the ligament becomes taut when the ipsilateral upper limb is adducted across the body or internally rotated; this motion results in traction of the suprascapular nerve at the spinoglenoid notch. Other possible mechanisms in which the suprascapular nerve may be compromised include Sandow and Ilic’s proposal that the suprascapular nerve nerve is vulnerable to direct compression by the medial border of the spinatus tendons at the spinoglenoid notch when the upper limb is abducted and externally rotated. [18] This mechanism would appear to be a further manifestation of posterior (or internal) impingement.

Ferretti, who has written extensively about volleyball shoulder, hypothesized that the mechanism of selective injury to the terminal portion of the suprascapular nerve in volleyball players is traction on the nerve due to repetitive, sudden, eccentric activation of the infraspinatus during the deceleration phase of the floater serve. [12, 15]

Another mechanism of injured is due direct compression on the nerve by a space-occupying lesion. Several studies have reported that the suprascapular nerve may be compressed in the vicinity of the spinoglenoid notch by ganglion cysts arising from the glenohumeral joint. [24, 37, 39, 40, 41] These ganglion cysts, like Baker cysts that occur in the popliteal fossa after meniscal degeneration or injury, are likely to be the consequence of an injury to the posterior glenoid labrum with resultant leakage of synovial fluid. [42]

Finally, some investigators have also proposed that suprascapular neuropathy can result from ischemia caused by migration of posttraumatic microemboli from the suprascapular artery (which generally follows a course parallel to the companion nerve) to the vasa nervorum.

Etiology

Sports that place a substantial load on the athlete’s shoulder when the upper limb is in an overhead or abducted and externally rotated position may precipitate this condition. The site of suprascapular neural entrapment determines whether the infraspinatus muscle alone or both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles are affected.

Although sports-related overuse mechanisms of suprascapular nerve injury are the most common causes, the SSN can also be damaged as a result of direct trauma as well as iatrogenic factors. The relationship of the nerve to the clavicle makes it vulnerable to injury after a clavicular fracture occurs. Surgical procedures involving the shoulder (eg, Bankhart repair) can place the nerve at risk for either direct injury or indirect injury. Interestingly, suprascapular neuropathy has also been reported to occur after positioning patients for spinal surgery.

Other diagnoses should be considered. Most commonly, the clinician diagnoses rotator cuff tendinopathy and prescribes a conservative treatment program. Because the rehabilitation programs for rotator cuff tendinopathy and infraspinatus syndrome are similar, in many (perhaps most) instances, the patient's condition improves, and the correct diagnosis goes unrecognized. Delayed-onset muscular soreness may be present, but this soreness is not expected to progress over 3 weeks. Rather, symptoms of delayed-onset muscular soreness tend to spontaneously resolve over 7-10 days.

Prognosis

As discussed earlier, the prognosis for a favorable clinical outcome is good. At the time of diagnosis, affected athletes report surprisingly little functional limitation. According to the literature, most cases respond favorably to either conservative treatment programs or, when indicated, surgical intervention. Furthermore, most athletes were able to return to their previous level of sports participation following therapeutic intervention.

-

Clinically relevant anatomy of the suprascapular nerve (SSN) and the structures it innervates. The SSN is vulnerable to entrapment at the superior scapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch, beneath the inferior transverse scapular ligament. The inset depicts the clinical appearance in an individual with predominantly right-sided atrophy of the infraspinatus muscle due to suprascapular neuropathy.