Introduction and Frequency

Groin injuries are commonly encountered by physicians and clinicians who treat athletes of all ages at all levels of competition. Groin injuries are particularly common in activities in which forceful adduction of the hip occurs; examples include skating, ice hockey, swimming, and soccer. In fact, as many as 10% of ice hockey–related injuries and 5% of soccer-related injuries are groin injuries. [1, 2] This article focuses on acute and chronic groin injuries related to sporting activities. Groin injuries resulting from major trauma (eg, multiple trauma, penetrating injuries) are not addressed, except to note that they require emergent medical evaluation.

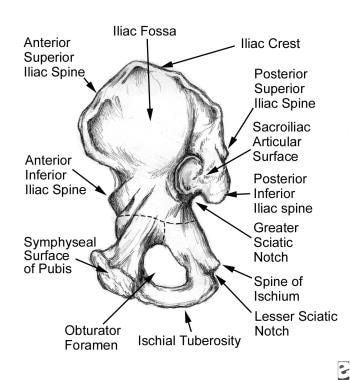

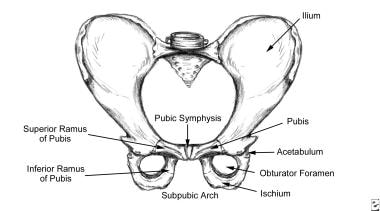

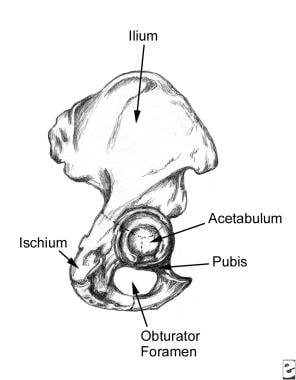

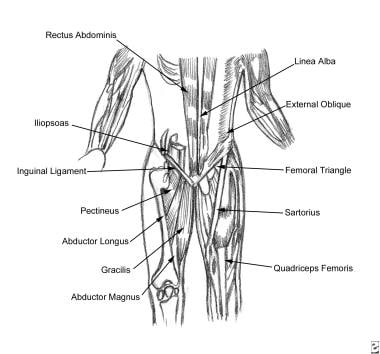

The images shown below illustrate the relevant anatomy of the pelvis relating to groin injuries.

Give special consideration to children, adolescents, and females with groin pain, because these conditions in this patient population may be erroneously attributed to minor trauma when they are, in fact, serious and require medical or surgical intervention. Evaluate any child aged 2-15 years with groin pain and an antalgic gait, especially if he or she has a fever. Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the hip, Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, septic arthritis, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis must be ruled out. [3] Consider early orthopedic consultation in any such case.

Hip pain in the adolescent athlete must take into consideration the relatively weaker growth plate of certain bony structures in the hip, and it should prompt the clinician to consider the diagnosis of apophyseal avulsion fractures. Apophysitis and apophyseal fractures are more common in skeletally immature athletes, in whom the physis is the weakest link in the muscle – tendon – bone complex. [4] Moreover, remember that children and adolescents may report knee pain that is actually referred from pathology in the hip, or vice versa. That is, complaints of both hip and lower-extremity pain in children and adolescents merit a detailed physical examination of the affected joint and surrounding structures.

The initial evaluation and conservative treatment for adult female athletes may be similar to that of male athletes. However, epidemiologic findings suggest that differences in female body mechanics may lead to subtly different injury patterns and a need for specialized rehabilitation services. [5, 6] Although anatomic differences are obvious, several factors play important roles in determining injury patterns in female athletes. These factors include (1) differences in metabolism, circulation, and cardiorespiratory capacity; and (2) differences in body shape, size, and composition. An example of such is the higher rate of patellofemoral disorders in female athletes, possibly accounted for by an increased quadriceps angle, less developed vastus medialis, and greater degree of genu valgum. [7]

Go to Female Athlete Triad, Low Energy Availability in the Female Athlete, and Osteitis Pubis for complete information on these topics.

Functional Anatomy and Sport-Specific Biomechanics

See the following images, which illustrate the relevant anatomy.

The hip joint is formed by the femoral head and its articulation with the acetabulum. The femoral neck and its bony prominences, the greater trochanter laterally and the lesser trochanter medially, are the attachment points for the major muscle groups of the hip. The abductor muscles of the hip, the gluteus medius and minimus, and the external rotators of the hip attach to the greater trochanter; the gluteus maximus, the main extensor of the hip joint, along with the hamstrings, attaches to the femur just distal to the greater trochanter. The lesser trochanter is the site of attachment for the iliopsoas muscle, the major hip flexor. [8]

The main blood supply to the femoral head and neck is the medial femoral circumflex artery, a branch of the common femoral artery. Disruption of the blood supply, through direct trauma (fractures of the femoral neck) or through vaso-occlusive disorders (sickle cell crisis), is related to the development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

There are approximately 18 bursae located throughout the hip joint. The superficial bursa located over the greater trochanter is a common source of pain as a result of inflammation; the deep bursa, or the gluteus medius bursa, is another common source of hip pain. The deep bursa lies between the gluteus maximus tendon and the posterolateral prominence of the greater trochanter. [8]

The hip is the largest joint in the body. The range of motion of the hip joint is impressive, second only to that of the shoulder joint. This factor, combined with the fact that the hip joint bears weight and is subjected to repetitive stress, makes this joint extremely susceptible to injury. In an Australian study of 29 elite soccer players, Verrall et al suggested that the development of chronic groin injury may be preceded by hip stiffness—that a restricted range of motion of the hip may in fact be a risk factor for this condition. [9] Even minor groin injuries can be difficult to rehabilitate.

Most groin injuries are related to stress and strain on the hip joint and the surrounding bony and muscular support structures of the pelvis. The most common injuries can be divided into acute and chronic injuries. The most common acute injuries are soft-tissue contusions and hematomas that result from direct force. The most common chronic conditions are strains of the muscle–tendon unit. [10]

Acute groin injuries may result from direct trauma encountered in contact sports (eg, football, ice hockey, basketball, rugby, soccer) and noncontact sports (eg, gymnastics). Acute muscle strains are commonly encountered in activities in which forced adduction of the hip occurs (eg, soccer, football, rugby, ice hockey, swimming [particularly with the breaststroke]) or in activities in which forced abduction of the hip occurs (eg, any sporting activity in which the athlete may perform a split, either accidentally or forcefully).

The causes of acute groin injuries may be considered causes of chronic (overuse) injuries. Chronic groin injuries tend to occur in those who participate in activities that promote overuse of the groin area (eg, swimming [particularly the breaststroke], ice hockey, speed and figure skating, soccer, running).

Go to Hip Pointer, Hip Tendonitis and Bursitis and Pediatrics, Sickle Cell Disease for complete information on these topics.

Approach to History Taking and Physical Examination

The approach to the athlete with groin pain can challenge the clinician for a variety of reasons. [11] The description and location of the pain is often vague. The anatomy of the groin can be clinically difficult to define.

The groin consists of the area where the abdomen meets the legs and includes the structures of the perineum. The groin, therefore, includes the following: the lower rectus abdominis musculature, the inguinal region, the symphysis pubis, the upper portions of the adductor muscles of the thigh, and the genitalia, as well as the scrotum in males.

The history and physical examination should be approached systematically to avoid missing the diagnosis. The clinician should assess for the onset of pain and whether the athlete can recall the inciting event, if any. The clinician should discuss factors that aggravate and alleviate pain, especially those pertinent to the sport in which the athlete participates.

The physical assessment requires the exposure of as much of the groin and hip as permitted, and the examination must include the following: inspection for symmetry and anatomic irregularity; palpation of the affected area for deformity; assessment of the range of motion of the articular structures near the area; rotation of the hip joint; observation for discrepancy of leg length; and evaluation of the patient's gait, including the performance of sprints, jumps, and activities that exacerbate the athlete's pain.

The differential diagnosis must take into consideration a number of medical conditions that affect the groin region in all individuals, not solely athletes. [4] These include the following:

-

Intra-abdominal disorders – Appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease

-

Genitourinary abnormalities – Urinary tract infections; sexually transmitted diseases; gynecologic, scrotal, and testicular abnormalities; nephrolithiasis

-

Referred lumbosacral pain from lumbar disc disease

-

Hip joint disorders – Osteoarthritis, Legg–Calve–Perthes disease, synovitis, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, osteochondritis desiccans

Because an estimated 27-90% of patients with groin pain have more than one coexisting injury, it is possible for clinicians to diagnose and manage one injury while a second injury goes unrecognized and untreated. [4, 12] The importance of a wide differential diagnosis is clearly evident from such a statistic.

The specific historical and physical examination findings germane to specific groin injuries will be discussed in the sections that follow. The patterns of pain described by patients, however, suggest types of pathologic processes at and around the hip joint. Pain that is aggravated by use and alleviated with rest suggests a structural problem, such as that encountered with osteoarthritis. Constant pain suggests an infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic process. [8]

Go to Urinary Tract Infection in Females and Urinary Tract Infection in Males for complete information on these topics.

Clinically Encountered Groin Injuries

Impact injuries

Impact injuries, such as those that occur during football, hockey, or other contact sports that produce high-speed collisions, usually result in contusions. However, such injuries may cause fractures of the pelvis (iliac wing); they may exacerbate previously asymptomatic inguinal hernias; and, in rare cases, they may produce bladder, testicular, or even urethral (straddle) injuries.

Any patient with lower abdominal or pelvic impact injury that causes severe groin pain, loss of function, or blood in the urine should be immediately evaluated by a physician. Findings from anteroposterior radiographs of the pelvis, hip images, and dipstick urinalysis are usually sufficient to rule out a serious acute injury. If no bony injury is discovered, conservative measures, namely, rest, application of ice for the first 24-48 hours, compression, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), may be implemented. A urologist should also evaluate the patient for hematuria.

Hip pointer

The hip pointer encompasses both impact and strain injuries of the hip. Forced extension of the hip may result in a sprain or avulsion of the sartorius muscle at its attachment to the iliac crest. These injuries are severely painful and difficult to rehabilitate. Contusions to the anterior superior iliac crest may involve the attachment of the sartorius muscle as well as the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, causing pain and paresthesias to radiate down the lateral aspect of the thigh. In some of these cases, especially those in which trochanteric bursitis is suspected, a local anesthetic or steroid injections may be given (at the physician's discretion) to treat severe pain. [13]

Groin pull

Acute strain injuries of the groin are epitomized by the groin pull. Multiple muscles, including the iliopsoas muscle, the adductor group, and the gracilis muscle, attach to the medial portion of the femur or pubis and help keep the legs together and flex the thigh. Falling, running, and quickly changing directions, as well as kicking or doing the splits (either intentionally or otherwise) can result in these injuries. Groin pulls can cause pain in the groin that radiates down the inside of the thigh.

The injury is usually focused at the musculotendinous junction and involves disruption of the fibers to various degrees and, occasionally, hematoma formation, which may delay healing. These weakened areas are repaired by fibroblasts, but they continue to be susceptible to repeat injury for a long time. [5] In fact, in a review of 1292 National Hockey League players, those with a previous groin injury had twice the risk of repeat injuries as that of athletes without a previous injury. [14] Furthermore, veteran hockey players had an injury rate 5 times greater than that of rookie players. [14]

In another review, the National Hockey League statistics revealed that adductor strains occurred 20 times more frequently during training camp than during the regular season, possibly related to the benefits of a strength-training program and to the fact that off-season deconditioning may contribute to these injuries. [4] In a study of male soccer players, adductor strain was responsible for 51% of all episodes of groin pain. [8]

Sometimes, the relevant muscles may actually tear loose from their bony attachments, taking a piece of the bone with it. If these avulsion fractures are severely displaced, surgical repair may be required. Most groin pulls eventually respond to conservative treatment that consists of rest, the application of ice, compression, and the use of NSAIDs. These injuries may be adequately managed by the team physician or trainer.

Injuries of the muscle–tendon units

Several muscle–tendon units are commonly strained and injured in athletes. The muscle most commonly strained and injured in the abdomen and groin is the adductor longus muscle. [10] Other muscle–tendon units that must be considered include the rectus femoris, the rectus abdominis, the sartorius, the gracilis, and the iliopsoas.

The rectus abdominis strain is an injury that may cause acute or chronic groin pain. This strain results from injury to the rectus muscle of the abdominal wall, which attaches to the pubis. This injury is fairly common in skaters, hockey players, and swimmers (especially breaststrokers). Severe tears and sprains of the rectus muscle are slow to recover; they may result in significant hematoma formation; and, on rare occasions, they may require surgical repair or reinforcement. [15]

Strain of the adductor longus may be managed in a variety of ways, depending on the location of the injury. Physical examination may reveal whether the injury lies within the muscle belly or within the tenoperiosteal attachment. Injuries to the muscle belly are best managed with gentle stretching, strengthening, and liberal return to activity. Injuries to the tenoperiosteal attachment require more conservative management: rest until the patient is pain free; gentle stretching and strengthening over a period of weeks; running and sprinting; and, lastly, running and sprinting combined with rapid changes in direction. [16]

In a study of 81 adult male athletes, Serner et al reported that following acute adductor injury, a longer period before return to sport is most strongly predicted by palpation pain at the proximal adductor longus insertion, a palpable defect, and/or, as found on MRI, a bone-tendon junction injury. [17]

Hernias

Hernias of the abdominal wall must be considered in patients who present with abdominal or groin pain. Hernia pain can be confused with pain due to chronic conditions encountered in a variety of sporting activities. Therefore, hernias represent a pathologic process that is frequently overlooked in the athlete. In fact, only 8% of patients with abdominal or inguinal hernias had detectible hernias on physical examination. [10] Therefore, a high index of suspicion is recommended when evaluating patients with groin or abdominal pain, and a hernia must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Herniography depicts a disorder in 84% of patients, and more importantly, 50% of these patients with abdominal wall defects do not have pain. [10]

Treatment for hernias is conservative and includes rest; the application of ice; gentle range-of-motion exercises; and, ultimately, surgical repair with mesh reinforcement of the abdominal wall (in more serious conditions). In comparing the recovery times for patients after hernia repair, Stoker and colleagues cited differences when open surgical repair was compared with laparoscopic repair. The authors suggested that full recovery may require as long as 2-3 weeks in patients with open surgical repair, whereas patients who undergo laparoscopic repair are more likely to resume participation in 1 week. [18]

Sportsman's hernia

The sportsman's hernia, or Gilmore groin, was first described by O.J. Gilmore in 1980. [19] It is a syndrome characterized by chronic groin pain that is associated with a dilated superficial inguinal ring, although the exact cause of this injury is largely speculative and likely multifactorial. [4] The true incidence of sportsman's hernia remains controversial; some authors believe it is only a rare cause of groin pain in athletes, but others believe it is the most common cause of chronic groin pain. [4]

The term "sportsman's hernia" is a misnomer, however, as there is typically no demonstrable hernia or defect in the groin or the abdominal wall. The definition of the sportsman's hernia, therefore, is any condition that causes persistent unilateral pain in the groin without a demonstrable hernia. [20]

The classic operative findings include laddering of the external oblique in conjunction with separation of the conjoint tendon from the ligament and laxity of the transversalis fascia. [21] Other studies have suggested abnormalities with the rectus abdominis insertion, avulsions of the internal oblique muscle fibers at the pubic tubercle, or entrapment of the ilioinguinal or genitofemoral nerves. [22]

Historically, the pain is described as chronic, located near the pubic tubercle, maximal on the evening of vigorous exercise or on the morning afterward, and exacerbated by activities that increase the intra-abdominal pressure. It is believed that sportsman's hernias are the result of chronic, repetitive trauma or stress to the musculotendinous portions of the groin, the pain of which develops insidiously, rather than acutely or dramatically. The sportsman's hernia is more commonly encountered in male than female athletes, and predictors of the development of groin injuries observed in professional hockey players included previous injury, nonaggressive conditioning in the off-season, and veteran, or older, players. [20]

On digital examination, the superficial inguinal ring is dilated. Evidence of herniation may or may not be palpable. The point of most tenderness is often the ipsilateral pubic tubercle. Pain can be elicited with a Valsalva maneuver or a resisted sit-up. Examination of the hip joint and evaluation of the athlete's gait typically reveal weakness with adduction.

Conservative therapies may temporarily alleviate the patient's pain, but definitive surgical management is recommended. Over 9 years, Gilmore repaired 360 injuries with a technique that used 6-layered reinforcement of the weakened transversalis fascia. Approximately 97% of his patients returned to competitive sports by the 10th week after postoperative care. [21] When conservative therapy does not result in alleviation of symptoms, surgical exploration is indicated, and placement of prosthetic meshes or patches, with or without neurectomy or ablation of the ilioinguinal nerve, has demonstrated success. [20]

Hip fracture or dislocation

The most severe and potentially debilitating groin injury is the hip fracture or dislocation. This injury normally results from a violent or high-speed collision or fall, for example, in skiing or playing hockey. The pain is usually severe and associated with an inability to bear weight and with a shortening and rotation of one leg inward or outward. Other severe injuries may be associated with the amount of force required to fracture or dislocate a hip. Immobilization and immediate medical attention and reduction (within the first few hours) are required to maximize the potential for recovery.

Stress fractures

Stress fractures of the femoral neck and the pubic ramus are the 2 most common stress fractures of the groin region. [23] Stress fractures are caused by repetitive minor trauma to the bones or muscular attachments. Therefore, these injuries are categorized somewhere between acute injuries and chronic injuries. Most stress fractures occur secondary to running (eg, in joggers or military recruits), although additional risk factors include relative osteoporosis in young female athletes secondary to nutritional or hormonal imbalances, muscle fatigue, changes in foot gear and training, or changes in intensity and/or duration of training. [23]

Stress fractures in the groin or hip can be difficult to diagnose and treat; these injuries most commonly occur at the femoral neck and inferior pubic ramus.

Femoral neck stress fractures are especially troublesome because they may lead to AVN of the femoral head and long-term disability. These may appear as a cortical irregularity or haziness on plain radiographs, but a magnetic resonance image (MRI) or a bone scan is usually required for the definitive diagnosis. The treatment is conservative, and recovery, although usually complete, may take months, especially if the athlete's activity is not significantly curtailed.

Avulsion fractures

Avulsion fractures of the hip must be considered in young athletes who give a history of severe, sudden-onset, and well-localized pain over a bony prominence. The relative weakness of the apophysis of the adolescent skeleton predisposes the young athlete to a variety of avulsion fractures. Examples include the following: avulsion of the anterior inferior iliac spine due to forceful flexion of the hip by the rectus femoris, avulsion of the ischial tuberosity by the hamstrings, and avulsion of the anterior superior iliac spine caused by the sartorius muscle.

Management for the majority of avulsion fractures is conservative and typically includes rest and gradual return to activity, aided by the use of analgesics. [24] Controversy exists regarding the management of avulsion fractures of the ischial tuberosity. Some authors advocate nonsurgical management. However, others have reported deficits in strength; function; and, in some cases, the formation of a painful callus, which prompts their advocacy of early surgical repair. [5] Depending on the size and amount of displacement of the fracture fragment, the injury may warrant surgical repair; this decision must be left to the judgment of the clinician.

AVN of the femoral head

AVN of the femoral head is a progressively debilitating condition that most often affects individuals in their third or fourth decade of life. An estimated 10,000-20,000 cases occur annually, at a mean age of 34 years. Although the pathogenesis is largely unclear, disruption of the circulatory supply to the femoral head either acutely or chronically results in cell destruction and necrosis, leading to collapse of the bony framework of the joint and resulting in arthritis. [23]

Risk factors for the development of AVN include high loads, sudden or irregular impact, and preexisting abnormalities such as dysplasia of the hip. [25] Tears of the labrum have been associated with developmental dysplasia [23] and early osteoarthritis and AVN. [25]

Ninety percent of cases of nontraumatic AVN are associated with systemic corticosteroid use for the management of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or autoimmune disorders. Heavy alcohol consumption has also been associated with the development of AVN. [23]

The diagnosis of AVN first begins with a high index of suspicion and radiographic confirmation of the lesion. Plain radiography may not demonstrate AVN until 3 months after the initial insult; therefore, MRI is the imaging modality of choice for identifying early AVN. MRI is both sensitive and specific (88-100%). [23]

Management includes rest, restricted weight bearing, and symptom control, although studies have demonstrated discrepancies between conservative management and early surgical core decompression. [23]

Osteitis pubis

Osteitis pubis (gracilis syndrome) is a chronic injury that causes resorption of the bone or cartilage of the pubic symphysis due to repetitive stress from kicking, lifting, running, or jumping. Osteitis pubis manifests as pain and tenderness in the region of the pubic symphysis. This injury is believed to be secondary to shearing and/or rotational movement of the pubic symphysis, and it is usually more severe when it occurs in postpartum women, in whom the injury results from the normal laxity of the pelvic ligaments during pregnancy that may persist for some time after delivery.

The patient's history reveals pain, most commonly during or after kicking. Physical examination reveals tenderness over the symphysis pubis. The pain in osteitis pubis results from limited rotation of the hip that transfers stress by shearing or by distraction across the symphysis and disrupts the joint.

Most cases of osteitis pubis are self-limited, and whether the cessation of activity or continued activity delays recovery is unclear. Most authors recommend continued flexibility training and muscle-strengthening exercises during the recovery phase of the injury. Groin support with neoprene shorts may provide some comfort.

Therapy with analgesics may be recommended. The use of corticosteroids is controversial; because corticosteroids are catabolic, some believe that their use may loosen the symphysis and result in a lack of integrity of the structure. [16] One case series, however, demonstrated a benefit when corticosteroids were used in athletes whose symptoms were 2 weeks or less in duration, whereas athletes whose symptoms lasted greater than 16 weeks required an additional 11-16 weeks for symptomatic improvement. [23]

A double-blind controlled study of 95 soccer players with groin pain from osteitis pubis were randomly treated with rehabilitation program without shock wave therapy (n=18); rehabilitation with shock wave therapy (n=26) or no treatment (n=51), the group with rehabilitation but no shock wave returned to soccer in a mean of 102.6 days, the group with rehabilitation and shock wave returned in a mean of 73.2 days compared to the control group which returned in a mean of 240 days. The 44 members of the groups which received rehabilitation had no recurrence of groin pain in the 1st year, whereas the control group had a recurrence rate of 51%. [26]

Recovery usually occurs over 2-3 months because of the relatively poor circulation to the region. Some authors note that the average healing time for osteitis pubis is 9-10 months, although most cases are self-limited. [23]

Bursitis

The last chronic or repetitive stress injury is bursitis. The body has special fluid-filled sacs called bursae, which provide lubrication in needed areas, such as the points where muscles move over bony projections. Bursae can become inflamed and irritated, resulting in pain when the overlying muscle is used. Subtle alterations in gait or gait impairment can increase the friction transmitted to the bursal sac. The result of increased friction is thickening of the normally thin bursa wall, leading to fibrosis and a gradual inability to lubricate the outer hip. Lateral hip pain that is aggravated by direct pressure is the classic pattern associated with trochanteric bursitis. [8]

The treatment is conservative, with most cases responding to NSAIDs and rest or to corticosteroid injections, used at the discretion of a physician. Persistent and recurrent bursitis may be due to rheumatic or arthritic disease or gout, which requires special medical treatment.

Meralgia paresthetica

Lateral hip pain accompanied by paresthesias or hyperesthesia is the presentation of lateral femoral cutaneous syndrome, or meralgia paresthetica. Pain that accompanies this disorder is described as a burning or an uncomfortable, heightened sensation. [8] The localized area of pain or hyperesthesia is not affected by direct pressure, movement of the hip joint, or movement of the lower back.

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is a pure sensory nerve whose path from the lumbosacral nerve plexus through the abdominal cavity and into the subcutaneous tissue of the thigh renders it susceptible to compression. The result of this compression is a localized area of hyperesthesia or paresthesia, in contrast to sciatica, a condition in which pain extends over a much wider area and extends down the leg and into the foot. [8]

Femoroacetabular impingement

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), or hip impingement, has become an increasingly recognized cause of hip pain in adolescents, adults, and athletes. It is believed to result from abnormal contact stress and joint damage around the hip, most notably from prolonged sitting, leaning forward, getting in and out of a vehicle, or performing a pivoting motion in sports. Clinically, pain may be described as either insidious or acute in onset. The clinical evaluation tool most sensitive for FAI is the flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (FADIR) test and reproduces the patient's pain along the anterolateral hip. [27]

Physiologically, it is believed to result from a bony deformity or spatial malorientation of the femoral head or the head/neck junction, acetabulum, or both. [28]

Evidence demonstrates that FAI may initiate osteoarthritis of the hip. Plain radiographic evaluation of the hip (anteroposterior pelvis and frog-leg lateral radiographs) may demonstrate pincer-type FAI, cam lesions, and osteophytes on the anterior femoral neck. [27] Arthroscopic evaluation demonstrates labral tears and acetabular cartilage lesions. It is believed that clinical and radiographic characteristics--namely, male sex, older age, Tonnis osteoarthritis grade, and elevated alpha angle--are associated with more severe intra-articular hip disease observed on arthroscopic evaluation, suggesting these characteristics may serve a predictive function in the evaluation of FAI. [29] Patients with more severe osteoarthritic changes demonstrated radiographically and patients with more severe cartilage damage observed intraoperatively are believed to have worse outcomes with treatment for FAI. [30]

Currently the mainstays of nonoperative treatment for FAI include occupational and physical therapy, restriction of activities that cause pain, core strengthening, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Surgical treatment, including surgical dislocation of the hip, arthroscopy, periacetabular and rotational osteotomies, and combined hip arthroscopy with limited open exposure, may be necessary to allow full return to activity. There is, however, no long-term prospective data to determine which therapeutic modality offers the most definitive result. [31]

Other injuries

Injuries to the groin that do not involve the bones or musculature are usually the result of a direct impact. All of the soft-tissue structures of the groin are susceptible to these types of injury. Injury to the genitalia (eg, penis, testis, urethra) or bladder, or traumatic inguinal or femoral herniation may occur. Reasons to suspect these injuries include blood in the urine; severe abdominal pain and tenderness (in the event of a bladder injury); persistent nausea, vomiting, or abdominal distention; and swelling in the femoral triangle or inguinal area (in the event of a hernia). All of these symptoms merit immediate medical evaluation in a hospital setting.

Diagnostic Tests

Plain radiography, technetium-99 (99 Tc) methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scanning, ultrasonography, nerve conduction studies, peritoneal radiography, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and MRI may be useful in the diagnosis of groin injuries.

Plain radiographs may show established osteitis pubis, a stress fracture (later stages), osteomyelitis (later stages), a slipped femoral epiphysis (epiphysiolysis), or osteoarthritis. Plain radiographs are useful in demonstrating the presence of hip abnormalities; one study found that 72% of male and 50% of female athletes evaluated with plain radiography demonstrated some evidence of radiographic hip abnormality, such as cam and pincer lesions associated with femoroacetabular impingement. [32]

A99m Tc-MDP bone scan may show osteitis pubis, a stress fracture, osteomyelitis, synovitis (occasionally bursitis), sacroiliitis, a tenoperiosteal lesion, or a muscle tear.

Ultrasonograms may show a muscle tear, hematoma, inguinal hernia, or bursitis (occasionally). Dynamic evaluation of the anatomic structures in the groin area through ultrasonography adds a significant amount of information to the imaging diagnosis, most notably in the evaluation of groin hernias. [33]

Nerve conduction studies may show ilioinguinal neuropathy or obturator neuropathy.

Peritoneal radiographs may show any inguinal hernia.

CT scans and MRIs may show AVN of the femoral head, disc pathology, radicular lesions, osteitis pubis, and other bone and soft-tissue injuries, as mentioned above. MRI with gadolinium has proven to be extremely valuable in the diagnosis of radiographically occult osseous abnormalities as well as soft tissue injuries like pubalgia, musculotendinous abnormalities, and bursitis. [34] MRI has been found to be 98% sensitive and 89-100% specific for injuries that involve the rectus abdominis, adductor tendon origins, and articular disease of the pubic symphysis. [34] Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) in the evaluation of intra-articular hip pain has been shown to be the best imaging modality for assessment of labral pathology (acetabular labral tears). [34]

A study by Hynes et al included athletes who underwent MRI for the investigation of groin pain. The researchers found that male athletes were significantly more likely than female athletes to have rectus abdominis-adductor longus, short adductor, or hip injuries. Pubic bone degenerative changes were more commonly detected in female athletes than in males. [6]

A study by Serner et al reported that more than 1 in 5 acute groin injuries showed no imaging signs of an acute injury and that clinically diagnosed adductor injuries were often confirmed on imaging, whereas iliopsoas and rectus femoris injuries showed a different radiological injury location in more than one-third of the cases. [35]

Medications

Topical and local anesthetics for injection in the management of the patient's pain include bupivacaine and lidocaine. For dosing regimens and product safety information, see the respective package inserts.

Injectable and systemic steroid preparations for inflammation also vary. Reviewing the dosing regimens and product safety information contained in the package insert before use is recommended.

Bentley recommended the injection of steroids in a small number of chronic conditions related to the groin and hip. [36] The attachment of the adductor longus to the inferior pubic ramus may be injected, and if the diagnosis is uncertain, the injection may be both diagnostic and therapeutic. However, conditions due to numerous etiologies have been erroneously treated with corticosteroid injections; these include the Gilmore groin and osteitis pubis.

In a study by Schilders et al, the authors found that a single entheseal pubic cleft injection of a local anesthetic and steroid may provide 1 year or more of relief of adductor-related groin pain in competitive athletes who have normal findings on MRI. [37] However, the authors also cautioned that such injections should only be for diagnostic purposes or for short-term treatment in competitive athletes who have evidence of enthesopathy on MRI. [37]

Drug Category: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAIDs have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic activities. The mechanism of action of these agents is not known, but they may inhibit cyclooxygenase activity and prostaglandin synthesis. Other mechanisms may exist as well; these may include inhibition of leukotriene synthesis, lysosomal enzyme release, lipoxygenase activity, neutrophil aggregation, and various cell-membrane functions.

-

Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), For mild to moderate pain and inflammation. Inhibits inflammatory reactions and pain by decreasing prostaglandin synthesis.

-

Naproxen (Anaprox, Naprosyn, Naprelan), For mild to moderate pain and inflammation. Inhibits inflammatory reactions and pain by decreasing prostaglandin synthesis.

-

Pelvis, symphyseal aspect.

-

Pelvis, frontal view.

-

Pelvis, lateral aspect.

-

Thoracoabdominal and proximal lower-extremity musculature.