Practice Essentials

Pes anserinus bursitis (also referred to as anserine or pes anserine bursitis) is an inflammatory condition of the medial knee. Especially common in certain patient populations, it often coexists with other knee disorders. [1, 2] Diagnosis of pes anserine bursitis should be considered when there is spontaneous pain inferomedial to the knee joint.

Bursae are small synovial tissue–lined structures that help different tissues glide over one another, as when a tendon slides over another tendon or bone. Bursae may become painful when irritated, damaged, or infected. The pes anserinus (anserine) bursa, along with its associated tendons, is located along the proximomedial aspect of the tibia.

Community-dwelling older adults can also present with complaints of knee pain in which pes anserine bursitis and other nonarticular conditions may play a role. Sporting activities, diabetes, obesity, and female sex are also associated risk factors that have been reported.

Pes anserine bursitis is primarily a self-limiting condition, which responds well to an exercise/stretching program. [3] Recalcitrant cases should be referred to a specialist to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other causes of the patient’s pain (eg, proximal tibial plateau stress fracture).

Signs and symptoms of pes anserine bursitis

Typical findings in patients with pes anserine bursitis may include the following:

-

Pain and tenderness over the inner knee

-

Local swelling

-

Chronic refractory pain in the area during aggravating activities in individuals with arthritis of the knee or in obese females

Diagnosis of pes anserine bursitis

The diagnosis of pes anserine bursitis usually is made on clinical grounds, and further workup is not necessarily indicated. In unusual cases (those that are persistent or suggestive of infection), a further workup can be obtained. In the rare cases where infection appears possible, appropriate laboratory studies may be ordered. If other pathology is suggested, radiography, radionuclide bone scanning, rheumatoid factor measurement, or other rheumatologic testing should be considered.

A diagnostic or therapeutic lidocaine or lidocaine-corticosteroid injection into the area of the pes anserine bursa may help the clinician to determine the contribution of pes anserine bursitis to a patient’s overall knee pathology, as well as possibly alleviate the patient’s symptoms.

Management of pes anserine bursitis

Pes anserine bursitis is primarily a self-limiting condition. [3] Patients generally are treated successfully with conservative measures.

Rest, including cutting back or eliminating the offending activities, is essential to therapy. Along with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), it represents first-line treatment.

Physical therapy is beneficial and often is indicated for patients with pes anserine bursitis. Rehabilitative exercise for persons with significant medial knee stress follows general physiatric principles for knee disorders and includes the following:

-

Stretching and strengthening of the adductor, abductor, and quadriceps groups (especially the last 30° of knee extension using the vastus medialis)

-

Stretching of the hamstrings

Intrabursal injection of local anesthetics, corticosteroids, or both constitutes a second line of treatment. Surgical therapy is indicated only in very rare cases.

Anatomy

Pes anserinus (“goose’s foot” in Latin) is the anatomic term used to identify the insertion of the conjoined medial knee tendons into the anteromedial proximal tibia; the name derives from the conjoined tendon’s webbed, footlike structure. From anterior to posterior, the pes anserinus comprises the tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles, each of which is supplied by a different lower-extremity nerve (femoral, obturator, and tibial, respectively). It lies superficial to the distal tibial insertion of the superficial medial collateral ligament (MCL) of the knee.

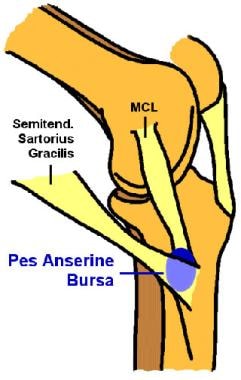

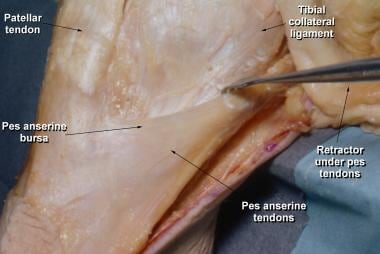

This bursa serves as a potential space where motion occurs. Its location is generally accepted to be between the conjoined tendons and the superficial MCL (tibial collateral ligament; see the images below). One recent anatomic investigation by ultrasound found variable locations in 170 individuals, most commonly between tendons and tibia and less frequently between MCL and tendons or among the tendons. [4] For various reasons such as injury or contusion, the synovial cells in the lining of the bursa may secrete more fluid, and the bursa may become inflamed and painful.

Pes anserinus bursa is located on proximomedial aspect of tibia between superficial medial (tibial) collateral ligament and hamstring tendons (ie, sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus). This bursa serves as space where motion occurs between these hamstring tendons and underlying superficial tibial collateral ligament.

Pes anserinus bursa is located on proximomedial aspect of tibia between superficial medial (tibial) collateral ligament and hamstring tendons (ie, sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus). This bursa serves as space where motion occurs between these hamstring tendons and underlying superficial tibial collateral ligament.

Another named bursa that is nearby, the musculi sartorii bursa, is smaller and located between the tendon of the sartorius and the conjoined tendons of the gracilis and the semitendinosus muscles; this bursa can communicate with the pes anserinus bursa proper. For the most part, the 2 bursae are regarded collectively as the pes anserinus bursa. In nonsurgical knees, there is usually no communication between these structures and the knee joint itself.

Pathophysiology

Pes anserine bursitis was initially described in the 1930s as an inflammation of the pes anserinus bursa underlying the conjoined tendons of the gracilis and semitendinosus muscles and separating them from the head of the tibia. [5] It was defined on the basis of observations of this type of bursitis in older adults with arthritis.

The sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles are primary flexors of the knee. These 3 muscles also influence internal rotation of the tibia and protect the knee against rotary and valgus stress. Theoretically, bursitis results from stress to this area (such as may result when an obese individual with anatomic deformity from arthritis ascends or descends stairs).

Pathologic studies do not indicate whether symptoms are attributable predominantly to true bursitis, to tendinitis, or to fasciitis at this site. [6] Panniculitis at this location has been described in obese individuals. However, controversy remains regarding the true pathophysiology of the clinical syndrome of pes anserine bursitis/tendinitis, because in many cases where the disorder’s presence is clearly suggested, imaging studies (ultrasonography) fail to demonstrate pathologic findings in the pes anserinus bursa or tendon. Indeed, a study by Atici et al found that, relative to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results, the sensitivity and specificity of the clinical diagnosis of pes anserine tendinitis/bursitis syndrome are low, at 41.2% and 59.5%, respectively. [7]

One case of gouty bursitis in the pes anserinus bursa has been described in a patient with known gout, elevated uric acid levels, periarticular MRI findings of pes anserine bursitis, and negative birefringent crystals on ultrasound-guided aspiration of the bursa. However, no contrast study was performed to fully exclude a communication with the articular space. [8]

One case of snapping pes anserine tendons was described associated with bursitis. [9]

Etiology

The main cause of pes anserine bursitis is underlying tight hamstrings, which are believed to place extra pressure on the bursa, causing a friction bursal irritation. [10] In addition, some patients may have bursal irritation due to a direct blow and thus experience a contusion to this area, as well as resultant inflammation.

Pes anserine bursitis is a common finding in patients who have concurrent Osgood-Schlatter syndrome, suprapatellar plical irritation, or other causes of joint irritation that may cause spasm of the hamstrings (eg, medial meniscal tears or underlying medial compartment or patellofemoral arthritis). Further clarification of the conditions predisposing to pes anserine bursitis is needed, including its mechanical causes and specific pathologic variants. The medical literature suggests that this disorder continues to be underrecognized as a cause of medial knee pain. [11]

Conditions associated with pes anserine bursitis include the following:

-

Degenerative joint disease of the knee – As many as 75% of patients with such disease may have symptoms of pes anserine bursitis

-

Obesity (especially in middle-aged women)

-

Valgus knee deformity, alone or in combination with collateral instability – This appears to increase the risk of pes anserine bursitis or tendinitis [12]

-

Pes planus (ie, flat foot) – This may predispose patients to pes anserine bursitis and to other problems in the medial knee

-

Sporting activities that require side-to-side movement or cutting

-

Local trauma, exostosis, and tendon tightness

-

Diabetes – Although diabetes was linked to bursitis in 2 studies, [13] the extent to which patients were able to control the diabetes was not documented

A prospective study by Uysal et al found pes anserine bursitis in 20% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis and indicated that the diameter and area of pes anserine bursitis correlates positively with the grade of osteoarthritis. The study, which involved 85 patients with primary knee osteoarthritis, also found a greater prevalence of pes anserine bursitis in female and older individuals with osteoarthritis. [14]

Similarly, a study by Kim et al found that in middle-aged and elderly persons examined with radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), pes anserine bursitis was more common in individuals with knee osteoarthritis than in those without (17.5% vs 2.2%, respectively) and was also more common in persons with knee pain than in those without (14.4% vs 2.5%, respectively). [15]

Another report, by Resorlu et al, indicated that the prevalence of bursitis in the medial compartment of the knee is higher in patients with severe osteoarthritis of the knee or medial meniscus tear. However, no association was found between the presence of chondromalacia patella and the occurrence of medial compartment bursitis. [16]

A retrospective study by Hall et al indicated that in adolescent female athletes, the risk of developing patellofemoral pain is greater in those who specialize in a single sport than in girls who participate in multiple sports but that this does not apply to the development of pes anserine bursitis. According to the study, which involved 546 basketball, soccer, and volleyball players, girls who played just a single sport had a 1.5-fold greater relative risk of patellofemoral pain than did those involved in multiple sports; however, no greater risk between the two groups was found for pes anserine bursitis and several other conditions. [17]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The exact incidence of pes anserine bursitis is unknown. It commonly is not recorded as an individual entity by many physicians, who may report the diagnosis simply as anterior knee pain or patellofemoral syndrome. This condition is recognized as occurring in a large number of patients who present to a physician’s office with anterior knee pain.

In a review of 509 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of symptomatic adult knees suspected of having an internal derangement, evidence of pes anserine bursitis was evident in 2.5%. [18]

In a study of beneficiaries of the United States’ Military Health System, Rhon et al found that out of 127,570 people with obscure or nonspecific knee diagnoses, pes anserine bursitis was diagnosed in 1.4% (accounting for 2-year follow-up). The vast majority of the cohort (99.7%) initially received a nonspecific diagnosis of “pain in joint, lower leg” (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th Revision [ICD-9], code 719.46), but eventually all but about 15% of nonspecific diagnoses were changed to a more specific one. However, the incidence of obscure diagnoses, which, in addition to pes anserine bursitis, included pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), prepatellar bursitis, and plica syndrome, was very small, the largest being plica syndrome, at 2.0%. [19]

Reports suggest that pes anserinus bursitis is far more common in overweight females, owing to the different angulation of the female knee, which puts more pressure on the area where the pes anserinus inserts. [20, 21]

In addition, pes anserine bursitis is associated with diabetes, occurring in 24-34% of patients with type 2 diabetes who report knee pain. [13, 22] A descriptive study of 94 patients with non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus identified pes anserine bursitis in 34 subjects, of whom 91% were women and 9% men. [13] Among affected women with diabetes, 62% had the disease bilaterally. None of the control subjects had bursitis without diabetes. Pes anserine bursitis is also associated with obesity, and on average, patients with diabetes in this study had greater body mass than the control subjects did. [13] However, the investigators noted that body mass alone did not explain the higher incidence of bursitis among individuals with diabetes.

Age-related demographics

Pes anserine bursitis is most common in young individuals involved in sporting activities and in obese, middle-aged women. This condition also is common in patients aged 50-80 years who have osteoarthritis of the knees.

In a study of 745 adults aged 50 years or older who had knee pain, the patient group with coexistent nonarticular conditions had significantly higher levels of pain severity and functional limitation than the group without such conditions did. [1] The presence of 1 or more nonarticular conditions accounted for a significant proportion of the variation in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) physical function scores, even when age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and severity of radiographic osteoarthritis were considered. Of 273 patients with nonarticular conditions, infrapatellar, prepatellar, or pes anserine bursitis was found in 35 patients.

Sex- and race-related demographics

The incidence of pes anserine bursitis appears to be higher among obese, middle-aged women. Among older individuals with arthritis, a slight preponderance of females over males is also noted among patients with pes anserine bursitis arthritis. The prevalence of anserine bursitis in women may result from the broader female pelvis and the greater angulation of women’s legs at the knees, which place additional stresses on these structures. [20, 21]

No racial predilection for pes anserine bursitis is reported in the literature.

Prognosis

By itself, pes anserine bursitis is usually a self-limiting condition. Rest, administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or injection brings about resolution in most cases; surgical intervention is required only rarely. A small risk of infection exists in recalcitrant cases in which the patient may have undergone an injection; however, if this procedure is performed properly under sterile conditions, the risk of infection is small.

Long-term sequelae are few if the individual decides to try to participate in sports or activities and play through the pain. Most athletes return to play sports. In most patients, a 6-8 week stretching and pelvifemoral strengthening exercise program alleviates the symptoms. Chronic arthritic diseases that frequently accompany bursitis obviously persist, but identification and treatment of pes anserine bursitis can significantly reduce pain.

Patient Education

Patients must be educated in the proper means of treatment and, in acute cases, need to allow adequate time for rest. In addition, they need to learn about the importance of proper exercises to rebuild the involved muscles; this is of particular value in helping older individuals with arthritis to avoid disuse atrophy. A home exercise program may be provided by the physical therapist. In athletic settings, patients, trainers, and coaches need to be educated regarding a gradual increase in the patient’s activity level and activity duration according to his or her symptoms.

For patient education resources, see the Arthritis Center, as well as Bursitis, Knee Pain, and Knee Injury.

-

Location of pes anserinus bursa on medial knee. MCL = medial collateral ligament.

-

Pes anserinus bursa is located on proximomedial aspect of tibia between superficial medial (tibial) collateral ligament and hamstring tendons (ie, sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus). This bursa serves as space where motion occurs between these hamstring tendons and underlying superficial tibial collateral ligament.