Practice Essentials

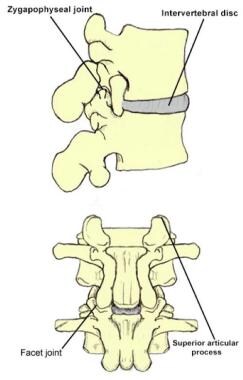

The facet joints are a pair of diarthrodial joints in the posterior aspect of two adjacent vertebrae of the spine. They are comprised of the inferior articular process of the vertebrae above, and of the superior articular process of the vertebrae below. [1] Although these joints are most commonly called the facet joints, they are more properly termed the zygapophyseal joints (abbreviated as Z-joints; also commonly spelled as "zygapophyseal joints"), a term derived from the Greek roots zygos, meaning yoke or bridge, and physis, meaning outgrowth. This “bridging of outgrowths” is most easily seen from a lateral view, where the Z-joint bridges adjoin the vertebrae. See the image below.

The 3-joint complex is formed between 2 lumbar vertebrae. Joint 1: Disc between 2 vertebral bodies; Joint 2: Left facet (zygapophyseal) joint; Joint 3: Right facet (zygapophyseal) joint.

The 3-joint complex is formed between 2 lumbar vertebrae. Joint 1: Disc between 2 vertebral bodies; Joint 2: Left facet (zygapophyseal) joint; Joint 3: Right facet (zygapophyseal) joint.

These facet joints are the only true synovial joints of the spine, with the presence of hyaline cartilage overlying the subchondral bone, synovial membrane and fibrous joint capsule. The facet joint is also sometimes referred to as the apophyseal joint or the posterior intervertebral joint.

As is true of any synovial joint, the Z-joint is a potential source of pain. The Z-joint is one of the most common sources of low back pain (LBP). The history and presence of Z-joint pain has been well studied. Despite all of these studies, the diagnosis of Z-joint–mediated pain remains a challenge as there are no history findings, complaints, or examination maneuvers found to be unique or specific to this entity. [2, 3] The Revel criteria are one such attempt to correlate symptom and physical examination signs with lumbar zyapophysial joint pain, albeit unsuccessfully. [4] Schwarzer et al and other authors have reported up to a 45% false-positive diagnostic rate when the physical examination findings are correlated to diagnostic medial branch blocks of the posterior rami. [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Authors have concluded that in most cases, Z-joints are not the single or primary cause of LBP. In fact, Z-joint pain is commonly mistaken for discogenic pain. Thus, many clinicians agree that correlating historical or physical examination findings with pain emanating from the Z-joint is a challenge. This review may help broaden the clinician's knowledge of this entity and may assist in making the diagnosis of lumbosacral facet joint syndrome.

Signs and symptoms

Although there are no clear pathognomonic signs or symptoms that are telling of pain originating from the facet joints, commonly reported symptoms among patients in this cohort include unilateral/bilateral axial low back pain. [4] They may have pain referred from upper facet joints extending into the flank, hip, and lateral thigh regions. Similarly, they may also have pain from lower facet joints radiating into the posterior thigh. Other symptoms include pain referral into the groin or thigh. [10]

Of note, Jackson et al demonstrated that the combination of the following seven factors was significantly correlated with pain relief from an intra-articular Z-joint injection [11] :

-

Older age

-

Previous history of LBP

-

Normal gait

-

Maximal pain with extension from a fully flexed position

-

The absence of leg pain

-

The absence of muscle spasm

-

The absence of exacerbation with a Valsalva maneuver

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Plain radiographs are traditionally ordered as the initial step in the workup of lumbar spine pain.

Given that no historical or physical examination maneuver is unique or specific to Z-joint–mediated LBP, fluoroscopically guided medial branch nerve injections are often used for diagnostic purposes to determine whether the Z-joint in question is responsible for LBP.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The initial treatment plan for acute Z-joint pain is focused on education, relative rest, pain relief, maintenance of positions that provide comfort, exercises, and some modalities.

Spinal manipulation may be useful for both short- and long-term pain relief.

Although radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of general LBP is controversial, one diagnosis for which it seems to have better outcomes is lumbar facet syndrome.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Related Medscape Reference topics include the following:

Background

The first discussion of the Z-joint as a source of LBP was by Goldwaith in 1911. [12] In 1927, Putti illustrated osteoarthritic changes of Z-joints in 75 cadavers of persons older than 40 years. [13] In 1933, Ghormley coined the term facet syndrome, suggesting that hypertrophic changes secondary to osteoarthritis of the zygapophyseal processes led to lumbar nerve root entrapment, which caused LBP. [14] In the 1950s, Harris and Mcnab [15] and McRae [16] determined that the etiology of Z-joint degeneration was secondary to intervertebral disc degeneration.

Hirsch et al were later able to reproduce LBP with injections of hypertonic saline solution into the Z-joints, thus affirming the role of the Z-joints as a source of LBP. [17] Mooney and Robertson also performed provocative hypertonic saline Z-joint injections and recorded pain referral maps with radiation mainly to the buttocks and posterior thigh. [18]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

LBP is the most common musculoskeletal disorder of industrialized society and the most common cause of disability in persons younger than 45 years. Given that 60% to 90% of adults experience LBP sometime in their lives, the fact that it is the second leading cause for visits to primary care physicians and the most frequent reason for visits to orthopedic surgeons or neurosurgeons is not surprising. As the primary cause of work-related injuries, LBP is the most costly of all medical diagnoses when time off from work, long-term disability, and medical and legal expenses are taken into account. [1]

The lumbosacral Z-joint is reported to be the source of pain in 15-45% of patients with chronic LBP. Ray believed that Z-joint–mediated pain is the etiology for most cases of mechanical LBP, [19] whereas other authors have argued that it may contribute to nearly 80% of cases. Thus, the diagnosis and treatment of this entity may help alleviate LBP in a significant number of patients.

International statistics

International data on lumbosacral facet syndrome have not been clearly established.

Functional Anatomy

The spine is composed of a series of functional units. Each unit consists of an anterior segment, which is made up of 2 adjacent vertebral bodies and the intervertebral disc between them, and the posterior segment, which consists of the laminae and their processes. One joint is formed between the 2 vertebral bodies, whereas the other 2 joints, known as the Z-joints, are formed by the articulation of the superior articular processes of one vertebra with the inferior articular processes of the vertebra above. Thus, the Z-joints are part of an interdependent functional spinal unit consisting of the disc-vertebral body joint and the 2 Z-joints, with the Z-joints paired along the entire posterolateral vertebral column.

In the lumbar spine, the superior articular processes face posteromedially, whereas the inferior articular processes face anterolaterally. The superior articular process has a concave orientation in order to accommodate the more convex orientation of the inferior articular process. The upper lumbar Z-joints are oriented in a sagittal plane, whereas the lower lumbar Z-joints approach a more oblique plane orientation. Thus, as the lumbosacral Z-joints maintain a progressive coronal orientation, greatest at the S1 level, they are functionally able to resist rotation in the upper lumbar region as well as resist forward displacement in the lower lumbosacral region.

The Z-joint is considered a motion-restricting joint, able to resist stress and withstand both axial and shearing forces. With extension of the spine, the Z-joints, along with the intervertebral discs, absorb a compressive load. In addition, the transmission of the Z-joint load occurs through contact of the tip of the inferior articular process with the pars of the vertebra below. The overloaded Z-joint then causes posterior rotation of the inferior articular process, resulting in stretching of the joint capsule.

If one considers the disc and each of the adjacent Z-joints as an interdependent functional spinal unit, degenerative changes within 1 of this 3-joint complex can influence each of the other 2 segments. Eighty percent of the loading stress is carried through the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs and 20% by the Z-joints. Thus, with the degeneration of the discs leading to loss of disc height, there is a relative increase in Z-joint load found with compression and extension maneuvers. Some authors postulate that Z-joints undergo osteoarthritic changes in response to disc degeneration secondary to changes in loading. This in turn results in arthropathy and slight angulation deformity, or a more horizontal orientation, which allows for degenerative spondylolisthesis to occur. Most commonly, this occurs at L4-5 and to a lesser degree at the superior levels. One theory is that these excessive Z-joint loads cause the inferior articular process to pivot about the pars and stretch the joint capsule, in addition to causing rostrocaudal subluxation (ie, Z-joint malalignment).

Although the focus is on the 3-joint complex as a functional unit, the associated ligamentous and fascial supports cannot be overlooked as they too can be a source of pain. The supraspinous ligament connects the tips of the spinous processes throughout the spine, whereas the interspinous ligaments connect the superior and inferior spinous process with extension from the ligamentum flavum to the thoracolumbar fascia. [20] These ligaments mainly limit flexion but likely assist in stability, especially from impaired posture with loss of lordosis.

The Z-joint is a common pain generator in the lower back. The 2 common mechanisms for this generation of pain are either (1) direct, from an arthritic process within the joint itself, or (2) indirect, in which degenerative overgrowth of the joint (eg, Z-joint hypertrophy or a synovial cyst) impinges on nearby structures.

The Z-joints are considered diarthrodial joints with a synovial lining, the surfaces of which are covered with hyaline cartilage that is susceptible to arthritic changes and arthropathies. Repetitive stress and osteoarthritic changes to the Z-joint can lead to zygapophyseal hypertrophy. Like any synovial joint, degeneration, inflammation, and injury can lead to pain with joint motion, causing restriction of motion secondary to pain and, thus, deconditioning. In addition, Z-joint arthrosis, particularly trophic changes of the superior articular process, can progress to narrowing of the neural foramen. In addition, as is the case for any synovial joint, the synovial membrane can form an outpouching called a synovial cyst. Z-joint cysts are most commonly seen at the L4-L5 level (65%), but they are also seen at the L5-S1 (31%) and L3-L4 (4%) levels. These synovial cysts can be clinically significant, particularly if they impinge on nearby structures (eg, the existing nerve root).

The neural foramen is bordered by the superior articular process, pars interarticularis, and posterior portion of the vertebral body. Z-joint hypertrophy or a synovial cyst can contribute to lateral and central lumbar stenosis, which can lead to impingement on the exiting nerve root (eg, radiculopathy). Thus, Z-joint pain can occasionally produce a pain referral pattern that is indistinguishable from disc herniation causing a radiculopathy.

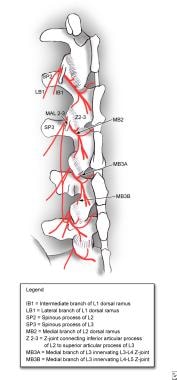

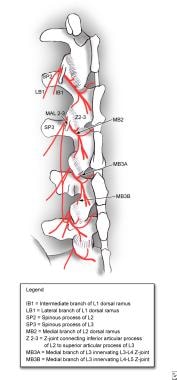

To understand the pattern of pain generation from the Z-joint, knowledge of the innervation pattern is essential. This pattern is frequently misunderstood even by experienced practitioners. Each Z-joint is innervated by branches of the dorsal ramus, termed the medial branch. The medial branch is 1 of 3 branches of the dorsal ramus, with the other 2 being the lateral branch (which does not exist for the L5 dorsal ramus) and the intermediate branch. The lateral branch innervates the iliocostalis muscle, and the intermediate branch innervates the longissimus muscle. The medial branch innervates many structures, including the Z-joint, but it also innervates the multifidus, interspinales, and intertransversarii mediales muscles, the interspinous ligament, and, possibly, the ligamentum flavum (see image below).

Dorsal ramus innervation (medial and lateral branches). MAL23 = mamillo-accessory ligament bridging the mamillary and accessory processes of L2 and L3; Z-joint = zygapophyseal joint.

Dorsal ramus innervation (medial and lateral branches). MAL23 = mamillo-accessory ligament bridging the mamillary and accessory processes of L2 and L3; Z-joint = zygapophyseal joint.

After the medial branch splits off from the dorsal ramus, it courses caudally around the base of the superior articular process of the level below toward that level’s Z-joint (eg, the L2 medial branch wraps around the L3 superior articular process to approach the L2-L3 Z-joint). The medial branch then continues in a groove between the superior articular process and transverse process (or, in the case of the L5 medial branch, between the superior articular process of S1 and the sacral ala of S1, which is the homologous structure to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae). As it makes this course, the medial branch is held in place by a ligament joining the superior articular process and the transverse process, termed the mamillo-accessory ligament (MAL) (see image below).

Dorsal ramus innervation (medial and lateral branches). MAL23 = mamillo-accessory ligament bridging the mamillary and accessory processes of L2 and L3; Z-joint = zygapophyseal joint.

Dorsal ramus innervation (medial and lateral branches). MAL23 = mamillo-accessory ligament bridging the mamillary and accessory processes of L2 and L3; Z-joint = zygapophyseal joint.

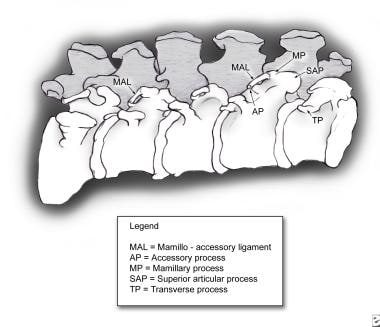

The MAL is so named because it adjoins the mamillary process of the superior articular process to the accessory process of the transverse process (see image below). The MAL is clinically important because it allows precise location of the medial branch of the dorsal ramus using only bony landmarks, which is essential for fluoroscopically guided procedures.

After passing underneath the MAL, the medial branch of the dorsal ramus gives off 2 branches to the nearby Z-joints. One branch innervates the Z-joint of that level, and the second branch descends caudally to the level below. Therefore, each medial branch of the dorsal ramus innervates 2 joints—that level and the level below (eg, the L3 medial branch innervates the L3-L4 and L4-L5 Z-joints). Similarly, each Z-joint is innervated by the 2 most cephalad medial branches (eg, the L3-L4 Z-joint is innervated by the L2 and L3 medial branches). Some authors have also suggested that the L5-S1 Z-joint has a unique triple innervation; in addition to the expected innervation by the L3 and L4 medial branches, the S1 medial branch emerging from the S1 posterior sacral foramen ascends cranially to also innervate the L5-S1 Z-joint. This has not, however, been consistently reported.

Understanding of this anatomy is crucial for procedures that attempt to obliterate Z-joint–mediated pain by blunting the innervation, whether through anesthesia (eg, a medial branch block) or denervation (eg, medial branch radiofrequency ablation [RFA]). [21] Practitioners commonly make the mistake of thinking that each Z-joint is innervated by the 2 adjoining medial branches (eg, that the L4-L5 Z-joint is innervated by the L4 and L5 medial branches of the dorsal rami, when it is actually innervated by the L3 and L4 medial branches). Two common reasons are cited for why practitioners make this mistake.

First, in the cervical region, the Z-joints are innervated by the 2 medial branches of the same name (eg, the C3-C4 Z-joint is innervated by the C3 and C4 medial branches), with the transition occurring at the T1-T2 Z-joint, which is innervated by the C8 and T1 medial branches. The second reason practitioners commonly confuse the innervation pattern is because they fail to recognize that the medial branch descends one level to reach the Z-joint. For example, the L2 medial branch courses around the L3 superior articular process, crosses underneath the L3 MAL, and then sends branches to the L2-L3 and L3-L4 Z-joints. Therefore, in a medial branch block, the medial branches closest to the Z-joint are targeted; they simply descended from a higher level.

Moreover, it is important to note that the medial branch of the posterior rami also innervates other posterior back structures. This has several important clinical implications. First, pain relief from anesthetizing the medial branch does not necessarily implicate the Z-joints as the primary pain generator, because one of the other structures innervated by the medial branch may have been the pain generator (eg, muscle or ligament). Second, denervation of the medial branch by RFA may affect the nerve supply to the multifidus muscle. This is important because lumbosacral radiculopathy is often another consideration in the differential diagnosis of LBP, which is directly tied to pathology of the multifidi.

One test to confirm the diagnosis of a lumbosacral radiculopathy is electromyography (EMG) of the multifidus muscle. Normally, denervation potentials in the multifidus muscle of a patient with LBP might be interpreted as evidence of a lumbosacral radiculopathy. However, in the context of a patient who has had RFA of the medial branch of the dorsal rami for the treatment of Z-joint pain, an alternative explanation for the denervation potentials in the multifidus would be denervation from the RFA, not from a lumbosacral radiculopathy.

The Z-joints contain nociceptive nerve fibers from nerves of the sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia, which can be activated by local pressure and capsular stretch. Nociceptive type IV receptors have been identified in the fibrous capsule and represent a plexus of unmyelinated nerve fibers and type I and II corpuscular mechanoreceptors. In addition, encapsulated type I and II nerve endings have been found to be primarily mechanosensitive and likely provide proprioceptive and protective information to the central nervous system.

In addition, the Z-joints have been found to undergo sensitization of neurons by naturally occurring inflammatory mediators such as substance P and phospholipase A2. Peripheral nerve endings release chemical mediators such as bradykinin, serotonin, histamine, and prostaglandins, which are noxious and can cause pain. Substance P has been implicated because of its ability to act directly on nerve endings or indirectly through vasodilation, plasma extravasation, and histamine release. Phospholipase A2 hydrolyzes phospholipids to produce arachidonic acid, causing an inflammatory reaction, edema, and prolonged nociceptive excitation.

In all, many sources of pain can be found at the Z-joint, ranging from degenerative changes to irritated nerve endings (chemical and mechanical) to concomitant nerve root entrapment.

Related Medscape Reference topics include the following:

Sport-Specific Biomechanics

Athletes involved in nearly any type of sport are susceptible to Z-joint injury. From linemen on a football team, gymnasts, or dancers, who may sustain repetitive and compressive forces to an extended spine, to baseball players or golfers, who perform repeated spinal rotational maneuvers, lumbosacral facet syndrome can impact athletes in many different types of sports and the arts.

Related Medscape Reference topics include the following:

Prognosis

With an active and focused spine rehabilitation program, the prognosis for these patients to achieve pain-free activity is good; however, the definitive diagnosis of Z-joint pathology is often difficult to make and challenging to confirm. For some patients, low back pain (LBP) may persist, and more aggressive interventions beyond conservative rehabilitation should be considered. Interventions such as medial branch blocks or neurolysis remain controversial, but they should be given consideration in the event conservative treatment remains inadequate and all other sources of LBP have been investigated. There is also emerging evidence that orthobiologics may have a role in addressing these symptoms, which could avoid a destructive treatment.

Complications

In some cases, lumbosacral facet syndrome can lead to chronic pain, time lost from employment or sports, and disability.

Interventional procedures, such as Z-joint injections with anesthetics and corticosteroids, can lead to transient lower-extremity weakness, insomnia, headache, fluid and electrolyte disorders (especially in patients with congestive heart failure), GI upset, bone demineralization, and impaired glucose tolerance (patients with diabetes). Less common effects are mood swings, increased appetite, and, the most serious, adrenocortical insufficiency. Dural puncture can lead to infection and an increased incidence of headaches. Anesthesia beyond local is rarely indicated and if administered could cause any of the possible risks (eg, prolonged grogginess, nausea, emesis, aspiration). [22]

Patient Education

Patient education is important for the recovery and rehabilitation of the spine in patients with lumbosacral facet syndrome. In the acute stage, patients must have a good understanding of their condition and of the possible detrimental effects of prolonged bed rest (ie, >2 days). Instruction in proper posture and body mechanics with activities of daily living is very important for these individuals. As pain becomes more controlled, the patient must be active in a progressive spine rehabilitation program, which later should be incorporated into a home exercise program for continued functional strengthening. Back safety and joint protection strategies should be incorporated throughout the rehabilitation process.

-

Dorsal ramus innervation (medial and lateral branches). MAL23 = mamillo-accessory ligament bridging the mamillary and accessory processes of L2 and L3; Z-joint = zygapophyseal joint.

-

Mamillary process anatomy.

-

Anteroposterior view of right L4-5 facet intra-articular injection with contrast. Courtesy of Carl Shin, MD.

-

Lateral view of right L4-5 facet intra-articular injection with contrast. Courtesy of Carl Shin, MD.

-

The 3-joint complex is formed between 2 lumbar vertebrae. Joint 1: Disc between 2 vertebral bodies; Joint 2: Left facet (zygapophyseal) joint; Joint 3: Right facet (zygapophyseal) joint.