Practice Essentials

Blount disease (also known as infantile tibia vara) is characterized by bowing (unilateral or bilateral) and length discrepancy in the lower limbs (see the image below). Blount disease has 2 primary types: infantile (early onset), which is typically noted between 2 and 5 years of age, and adolescent (late onset), which occurs after 10 years of age. Approximately 80% of infantile cases and 50% of late-onset cases are bilateral. A nontender bony protuberance can be palpated along the medial aspect of the proximal tibia, representing the deformed medial tibial metaphysis. [1, 2, 3]

Radiographic changes found in Blount disease are usually diagnostic. Radiographs provide the most information of this disease because they can be obtained with the patient in an erect position and they provide broad coverage of the area of interest. The long-leg anteroposterior radiograph shows both legs from the hips to the ankles and is the standard screening radiograph for early onset Blount disease. Overall, varus can be quantified on this view. Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee are often also obtained. [3]

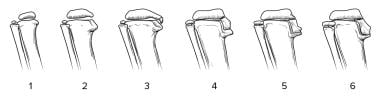

The Langenskiold classification distinguishes 6 radiographic stages of Blount disease and is the most commonly used classification system for the radiologicic features of this disease. Only irregular metaphyseal ossification exists in disease stages I and II, which can potentially be managed nonoperatively. At these stages, Blount disease is difficult to distinguish from physiologic bowing. Beyond stage III, there is significant deformity of the tibial epiphysis and physis with fragmentation. Bar formation can occur in stage IV and can progress to stage V, with disruption of the physeal cartilage. In stage VI, there is significant depression of the articular surface and bar formation. [4, 5, 3, 6, 7]

MRI is helpful in neglected or delayed forms of Blount disease in patients older than 4 years but before the development of radiographic epiphysiodesis. MRI provides structural information on the cartilage, menisci, and ligaments, as well as on the blood supply to the growth plates. At the tibial epiphysis, MRI allows measurement of the cartilaginous tibial slope, which is a more accurate parameter than the bony tibial slope measured on radiographs. [3] MRI can have limited usefulness in the differential diagnosis of difficult cases. Such cases include those in patients with early growth-plate and marrow changes that are not specific enough to be diagnosed as Blount disease by radiographic findings. [8, 9, 10, 11]

In patients with early changes, it is difficult to differentiate physiologic bowing from other conditions by radiography. Changes in the growth plate are not easy to detect on radiographs.

MRI cannot be performed with the patient in the erect position, and it does not provide coverage broad enough to diagnose Blount disease. In addition, MRI is more expensive than radiography, particularly because many patients must undergo repeat imaging to evaluate the changes due to Blount disease.

Infantile Blount disease. Radiograph in a 21-month-old boy shows bilateral bowing with definitive medial tibial beaking on the left. On the right, the appearance is consistent with physiologic bowing or early Blount disease. Follow-up radiographs were required.

Infantile Blount disease. Radiograph in a 21-month-old boy shows bilateral bowing with definitive medial tibial beaking on the left. On the right, the appearance is consistent with physiologic bowing or early Blount disease. Follow-up radiographs were required.

Erlacher reported the first case of tibia vara in 1922. [12] In 1937, Blount reported 13 more cases and reviewed all of the 15 cases that were reported in the literature up to that time. Blount suggested the term tibia vara; however, the eponym drawn from his name remains in common use. [13]

In North America and the Caribbean, Blount disease mainly affects obese African American children. Without treatment, the prognosis is often severe, particularly in the infantile form because of development of medial tibial epiphysiodesis at about 6 to 8 years of age. In other parts of the world, the associations with black ethnicity and obesity are less obvious and the prognosis is often less severe. Before 4 years of age, progressive Blount disease should be corrected by a simple osteotomy. However, once medial tibial epiphysiodesis has developed, both a complementary epiphysiodesis and gradual external fixator correction of the other alignment abnormalities, rotational deformity, and limb length are required. [14]

Recurrence of Blount disease is diagnosed when the femorotibial angle (FTA) is more than 10° varus at follow‐up. The rate of recurrence may be decreased by performing the initial surgery at an early age. [15]

LaMont and colleagues evaluated a new modified classification for recurrence of Blount disease after surgical intervention for infantile tibia vara and reported that patients with metaphyseal defect slopes that run downward vertically with no upward curvature projecting medially are prone to having a higher recurrence rate. [16]

Normal age-related angulation changes in the knee joint

A pronounced varus angulation is seen in newborns and in children younger than 1 year. Varus angulation is believed to be secondary to in utero molding of the lower extremities, and this gradually resolves after children start walking.

Varus angulation usually corrects by the time children reach approximately 18-24 months of age or after they have been walking for approximately 6 months.

During the ages of 2 and 3 years, pronounced valgus angulation changes occur. The valgus position then partially corrects over the following few years, reaching the adult pattern of mild valgus by 6-7 years of age. Any varus angulation at the knee joint seen in individuals older than 2 years is therefore considered abnormal, and such a finding is the basis for the diagnosis of tibia vara, or Blount disease.

Radiography

Radiography is the primary modality used to diagnose tibia vara (Blount disease). Radiographic findings primarily involve the posteromedial parts of the proximal tibial epiphysis, growth plate, and metaphysis. A standing anteroposterior radiograph of both legs is used to demonstrate bowing and abnormality at the medial aspect of the proximal tibia. In more advanced cases, bowing is seen at both ends of the tibia. On lateral knee radiographs, a posteriorly directed projection at the proximal tibial metaphyseal level is seen.

Different radiologic measurements have been used in an attempt to confirm the presence of Blount disease. The femoral-tibial angle helps confirm the varus position of the leg, but it can be misleading secondary to the rotation of the leg, which may be positional or caused by a coexisting rotational abnormality.

The metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle has been suggested to provide more precise indications of Blount disease than the femoral-tibial angle, as shown below. The metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle is obtained by measuring the angle formed between a line drawn parallel to the top of the proximal tibial metaphysis and another line drawn perpendicular to the long axis of the shaft of the tibia. Overlap may be found in measurements between patients with and without tibia vara.

Infantile Blount disease. Radiograph in a 21-month-old boy shows bilateral bowing with definitive medial tibial beaking on the left. On the right, the appearance is consistent with physiologic bowing or early Blount disease. Follow-up radiographs were required.

Infantile Blount disease. Radiograph in a 21-month-old boy shows bilateral bowing with definitive medial tibial beaking on the left. On the right, the appearance is consistent with physiologic bowing or early Blount disease. Follow-up radiographs were required.

Angle measurements are 9º ± 3.9º in cases of physiologic bowing and 19º ± 5.7º in patients with Blount disease. Reportedly, angles greater than 20º confirm true tibia vara in children, whereas angles of 15-20º may or may not indicate tibia vara.

Another angle used is the tibial metaphyseal-metaphyseal angle. This angle is larger than the metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle in children with the most marked bowing and indicates distal tibial bowing in severe cases.

In 1952, Langenskiold first proposed a 6-stage classification of radiographic changes. This remains the most commonly used system. [17, 18, 19] This classification was not intended for use in determining the prognosis or the most desirable type of treatment, and the author cautioned against such use. However, the fact remains that surgical treatment commonly is needed for any child with stage 3-6 changes. [20, 21]

(See the images below.)

Depiction of the 6 stages of the Langenskiold classification of tibia vara, as they would be seen on radiographs.

Depiction of the 6 stages of the Langenskiold classification of tibia vara, as they would be seen on radiographs.

Adolescent Blount disease in a 12-year-old girl. Image shows mild changes in the medial tibia. The growth plate is widened and slightly depressed.

Adolescent Blount disease in a 12-year-old girl. Image shows mild changes in the medial tibia. The growth plate is widened and slightly depressed.

Sabarwhal and Zhao attempted to establish reference values for the hip-knee-ankle angle and assess the relationship between it and the anatomic femoral-tibial angle in children by studying standing full-length radiographs of lower extremities without abnormalities. They measured the angle between a line connecting the center of the ossified femoral head and the center of the distal femoral epiphysis and another line connecting the center of the distal femoral epiphysis and the center of the talar dome. The authors found that there was a linear relationship between the hip-knee-ankle and anatomic femoral-tibial angles in the children. Despite varying hip-knee-ankle angles at different ages, the mean absolute difference between that angle and the anatomic femoral-tibial angle remained relatively constant. [22]

Lavelle et al compared the 2 techniques to measure the tibial metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle (MDA), involving the use of both the lateral border of the tibial cortex and the center of the tibial shaft as the longitudinal axis for radiographic measurements. The use of digital images, according to the authors, poses another variable in the reliability of the MDA. They found that using either the lateral diaphyseal line or center diaphyseal line produces reasonable reliability with no significant variability at angles of 11º or less or greater than 11º. [23]

In the most severe cases, the diagnosis can be made with a high degree of confidence in the presence of a tibial metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle measurement of 20º or more. However, in less-severe cases, measurements may not be confirmatory, and differentiating tibia vara from physiologic bowing is difficult. In such patients, 6 months of follow-up observation is recommended (see image below).

Infantile Blount disease. Radiograph in a 21-month-old boy shows bilateral bowing with definitive medial tibial beaking on the left. On the right, the appearance is consistent with physiologic bowing or early Blount disease. Follow-up radiographs were required.

Infantile Blount disease. Radiograph in a 21-month-old boy shows bilateral bowing with definitive medial tibial beaking on the left. On the right, the appearance is consistent with physiologic bowing or early Blount disease. Follow-up radiographs were required.

Degree of confidence

Extreme physiologic bowing may cause false-positive results. Early or less-severe Blount disease may be misdiagnosed as physiologic bowing of the legs when measurements and medial tibial changes are not confirmatory.

Some authors have suggested that children with a metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle greater than 11º eventually develop tibia vara, whereas those with measurements less than 11º have physiologic bowing. Other authors have found standard deviations of ± 2.6º and ± 4.6º. Still others have recommended 6 months of follow-up observation to better differentiate the 2 conditions.

The differential diagnosis of Blount disease includes physiologic bowing, congenital bowing, rickets, Ollier disease, trauma, osteomyelitis, and metaphyseal chondrodysplasia.

Difficulty may be encountered in differentiating infantile tibia vara from physiologic bowing of the legs. However, the proximal tibial angulation is acute in Blount disease, occurring immediately below the medial metaphyseal beak. This feature results in a metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle greater than 11º. In physiologic bowing, angular deformity results from a gradual curve involving both the tibia and the femur.

Congenital bowing must be considered. The angulation may occur in the middle portion of the tibia, with a normal-appearing distal femur and proximal tibia.

Mild or healing rickets with residual bowing may be difficult to differentiate from stage 2 infantile tibia vara. However, rickets affects the skeleton in a generalized and symmetric fashion, with loss of the zone of provisional calcification in the physis. In addition, the typical biochemical abnormalities of rickets help differentiate the conditions.

Ollier disease may result in tibial bowing but can be differentiated easily on radiographs by the presence of enchondromas. [24]

Regarding trauma, growth-plate injuries of the proximal tibia may result in a deformity resembling tibia vara.

Osteomyelitis may be another mimic. Growth plate disturbance secondary to infection may result in an appearance similar to that of Blount disease.

In patients with metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, multiple metaphyseal deformities are seen, as is a short stature. Radiologically, the changes in this condition mimic those of rickets, but no abnormal serum biochemical results are noted.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

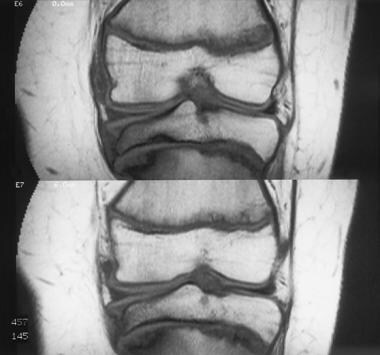

Although radiographic findings in Blount disease are usually diagnostic, MRI has the advantage of direct depiction of the epiphysis and the growth plate. How MRI can aid in evaluation and treatment of patients with Blount disease is debatable. MRI has a distinct advantage in a subset of patients with advanced or recurrent tibia vara. In these patients, MRI can demonstrate the extent of the physeal bar to quantify the percentage of physeal involvement. On a T2-weighted image, an open physis is bright and the physeal bar appears black. Early physeal fusion of the medial proximal tibial and, less frequently, medial distal femoral physis can occur from the injury of chronic weight bearing. This injury can lead to progressive genu varus from medial tethering of the growth plates. Removal of the physis medially may help restore normal growth. [25, 26, 27]

An article about MRI changes in bowleg deformities of early infancy suggested a possible role for MRI in differentiating physiologic bowing from Blount disease. [28] Children who eventually had Blount disease were found to have a depression of the medial physis and abnormal signal intensity in the metaphysis in addition to the lesion in the epiphysis. In comparison, children with physiologic bowing were found to have high signal intensity only in the epiphyseal cartilage. However, most patients with combined changes did not develop Blount disease. [10, 11]

(See the image below.)

Adolescent Blount disease. Coronal T1-weighted MRIs of the left knee in an 11-year-old boy show Blount disease affecting the entire tibial growth plate and the lateral part of the distal femoral plate. Signal intensity changes in the marrow of the metaphysis and epiphyseal flattening are evident in the medial portion of the tibia; this is the classic depiction.

Adolescent Blount disease. Coronal T1-weighted MRIs of the left knee in an 11-year-old boy show Blount disease affecting the entire tibial growth plate and the lateral part of the distal femoral plate. Signal intensity changes in the marrow of the metaphysis and epiphyseal flattening are evident in the medial portion of the tibia; this is the classic depiction.

MRI does not yet have a well-established role in the evaluation of Blount disease. MRI can be useful to the orthopedist who wishes to know which portion of the medial knee (epiphysis, physis, metaphysis) is injured and what corrective steps must be undertaken. MRI is also useful in the assessment of possible development of a physeal bar.

Nuclear Imaging

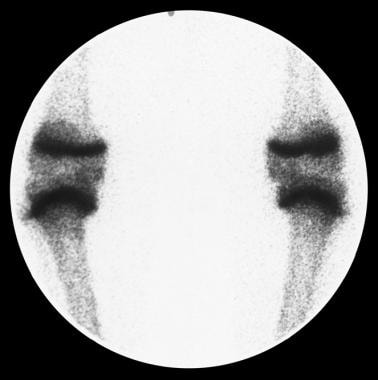

Multiphase bone scintigraphy is sensitive in assessing normal and abnormal growth plate functions in the growing skeleton. [29] Mechanical loading and stress factors influence scintigraphic uptake at the growth plate. When immobilization is prolonged and when closure begins, growth-plate activity decreases.

In patients with angular deformities of the legs, the half of the growth plate with greater mechanical loading becomes more active than the other half. In patients with Blount disease, increased uptake occurs medially in the tibial plate, and scintigraphic changes may also be seen in the distal femur. Scintigraphy is not used for diagnosis, but it can be useful in making treatment decisions.

(See the image below.)

Blount disease scintigraphy. Bone scanning is used to assess growth-plate activity in a 10-year-old boy. Affected areas show increased physeal uptake until closure begins. At that time, activity decreases. The proximal tibial growth plate on the right has increased uptake throughout. On the left, the medial tibial physis has begun to close.

Blount disease scintigraphy. Bone scanning is used to assess growth-plate activity in a 10-year-old boy. Affected areas show increased physeal uptake until closure begins. At that time, activity decreases. The proximal tibial growth plate on the right has increased uptake throughout. On the left, the medial tibial physis has begun to close.

-

Infantile Blount disease. Radiograph in a 21-month-old boy shows bilateral bowing with definitive medial tibial beaking on the left. On the right, the appearance is consistent with physiologic bowing or early Blount disease. Follow-up radiographs were required.

-

Bilateral Blount disease. Radiograph in a 2.5-year-old girl with bowing, which is more severe on the left. The proximal left tibia shows a medial beaking deformity. The metaphyseal-diaphyseal angles are 24° on the left and 14° on the right.

-

Blount disease scintigraphy. Bone scanning is used to assess growth-plate activity in a 10-year-old boy. Affected areas show increased physeal uptake until closure begins. At that time, activity decreases. The proximal tibial growth plate on the right has increased uptake throughout. On the left, the medial tibial physis has begun to close.

-

Adolescent Blount disease. Coronal T1-weighted MRIs of the left knee in an 11-year-old boy show Blount disease affecting the entire tibial growth plate and the lateral part of the distal femoral plate. Signal intensity changes in the marrow of the metaphysis and epiphyseal flattening are evident in the medial portion of the tibia; this is the classic depiction.

-

Adolescent Blount disease in a 12-year-old girl. Image shows mild changes in the medial tibia. The growth plate is widened and slightly depressed.

-

Adolescent Blount disease. Moderate-to-severe changes in the proximal left tibia are demonstrated on this radiograph. Note the depression of the plateau, beaking, and metaphyseal sclerosis. The tibial growth plate is widened and irregular. Note that the distal femoral growth plate shows changes as well. Mild irregularity and slight widening are seen.

-

Depiction of the 6 stages of the Langenskiold classification of tibia vara, as they would be seen on radiographs.