Practice Essentials

Esophageal tear is defined as a breach of the esophageal wall resulting from a mucosal tear, perforation, or rupture. Tears of the esophagus are life-threatening conditions that require prompt diagnosis and emergency treatment. Esophageal perforations allow the upper gastrointestinal (GI) contents to egress from the esophageal lumen into the soft tissues of the neck, the mediastinum and pleural space, the peritoneal cavity, and other possible sites (depending on the location of the injury). If esophageal tears remain untreated, then cervical soft tissue infections, mediastinitis, pleuritis, or peritonitis will develop, followed by systemic sepsis and death.

Esophageal perforations, Mallory-Weiss tears, and esophageal hematomas may result from traumatic injury to the esophagus following instrumentation, such as after gastric lavage or upper GI endoscopy. Recent increases in the use of diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy and esophageal surgery have made endoscopic instrumentation the most common cause of esophageal rupture. [1]

Boerhaave syndrome, Mallory-Weiss syndrome and rare spontaneous esophageal hematomas are all forms of esophageal tear that usually occur during vomiting. Other precipitating factors of spontaneous tears include straining, hiccupping, coughing, primal scream therapy, blunt abdominal trauma, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or any event accompanied by a marked and often sudden elevation of abdominal pressure. In a few cases, no apparent precipitating factor can be identified.

Preferred examination

Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus is a condition that is still often diagnosed late despite presentations with classic histories and/or abnormal chest radiographs. Endoscopic assessment of perforations is safe; in combination with a contrast-swallow study, the results can confidently predict the success of nonoperative management in patients with contained or controlled ruptures. [2]

Conventional radiographs are generally used in the initial assessment of patients with suspected esophageal perforation; this is followed by an oral contrast-enhanced examination, which can be critical in determining the presence and precise location of an esophageal perforation. Conventional radiographs may be normal in up to 10% of patients with esophageal perforations. Endoscopy, oral contrast-enhanced studies, and angiography are invasive procedures.

Endoscopy is safe and is extremely useful, particularly if an esophageal tear is suspected. Most signs seen on conventional radiographs are better depicted on CT scans.

MRI scanning can depict the normal esophageal and mediastinal anatomy and has been used in the diagnosis of esophageal masses, varices, and esophagitis; however, the role of MRI in an emergency setting, particularly in the diagnosis of esophageal rupture, has not been defined.

Mediastinitis often accompanies esophageal perforation, where an expected fluid low signal intensity may be depicted on T1-weighted MRI scanning, and a high signal intensity may be depicted on T2-weighted and proton density–weighted images. [3]

(See the images of esophageal tear below.)

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in previous image).

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in previous image).

Early diagnosis and management are imperative to minimize complications of enteric leakage into the thoracic or abdominal cavity and prevent consequent sepsis and multisystem organ failure. [4] Factors impacting morbidity and mortality include the cause and site of the perforation, the time to diagnosis, and the therapeutic procedure. [5]

Treatment options include observation if contained, endoscopic therapy (usually stent placement) if the perforation is of limited size, or surgical management when a large perforation with gross contamination is present. [6]

Pittsburgh Severity Score

The Pittsburgh Severity Score (PSS) is a clinical score based on preexisting esophageal pathology and clinical findings at the time of presentation. Developed at the Univerity of Pittsburgh and subsequently validated in a separate cohort of patients, PSS has been found to predict the need for surgical management, as well as mortality. All variables are assigned points (range, 1-3) for a possible total score of 18. Points are given to each variable according to the following scale [7] :

-

1 = age >75 years

-

1 = tachycardia (>100 bpm)

-

1 = leukocytosis (>10,000 white blood cells/mL)

-

1 = pleural effusion (on chest radiograph, computed tomography, or barium swallow)

-

2 = fever (>38.5°C. or 101.3°F)

-

2 = noncontained leak (on barium swallow or computed tomography)

-

2 = respiratory compromise (respiratory rate >30 breaths/min)

-

2 = increasing oxygen requirement (or need of mechanical ventilation)

-

2 = time to diagnosis >24 hours

-

3 = presence of cancer or hypotension

A PSS greater than 5 is predictive of a greater than 3-fold increase in the need for surgical management and carries a 27% risk of death; a PSS greater than 9 carries 0% survival. Patients with a true esophageal perforation in whom diagnosis and time to treatment are delayed typically have a higher PSS and poorer outcome. [6]

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicineHealth's Digestive Disorders Center.

Radiography

Plain radiographs are noninvasive and can be obtained in most emergency situations. Radiographs of esophageal tears show positive signs in 80-90% of cases. Esophageal tears are not directly identified on conventional radiographs; the clinician must rely on indirect signs along with a high index of suspicion. Conventional radiographs are normal in 9-12% of confirmed esophageal perforations.

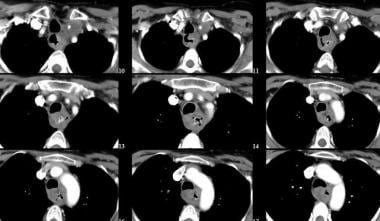

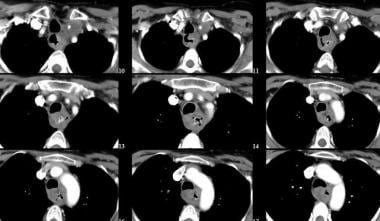

Axial post-contrast CT images through the neck show a soft tissue mass in the upper esophagus. Note the air within the posterior high esophageal mass. A biopsy (not revealed) depicted a squamous cell carcinoma. The mass extends into the neck on the left, encasing the left external carotid artery.

Axial post-contrast CT images through the neck show a soft tissue mass in the upper esophagus. Note the air within the posterior high esophageal mass. A biopsy (not revealed) depicted a squamous cell carcinoma. The mass extends into the neck on the left, encasing the left external carotid artery.

(See the radiographic images of esophageal tear below.)

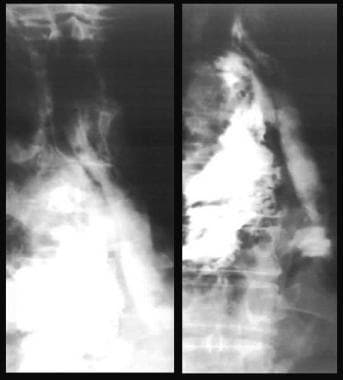

A contrast-swallow study that shows leakage of contrast agent at the level of the carina (same patient as in previous image).

A contrast-swallow study that shows leakage of contrast agent at the level of the carina (same patient as in previous image).

Water-soluble contrast study of the upper esophagus shows leakage of contrast material after instrumentation.

Water-soluble contrast study of the upper esophagus shows leakage of contrast material after instrumentation.

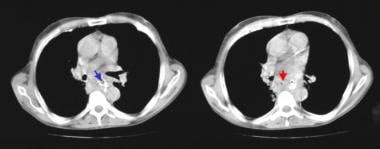

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in following image).

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in following image).

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in previous image).

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in previous image).

Mallory-Weiss tears are not seen on conventional radiographs and may not be visualized on contrast radiography of the esophagus. Pneumothorax, mediastinal emphysema, mediastinitis, and hydrothorax have many causes; there is a potential for false-positive and false-negative diagnosis.

Upper and mid esophageal perforations

The most frequent site of upper and mid esophageal perforations is at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle, and most perforations are iatrogenic. The conventional radiographic findings include widening of the precervical soft tissues, air in the precervical soft tissues, widening of the superior mediastinum, and a right-sided hydrothorax.

Lower esophageal perforations

Boerhaave ruptures usually occur in the left inferior posterolateral wall of the esophagus. The tear is not directly identified on chest radiographs; the clinician must rely on indirect signs along with a high index of suspicion. These indirect signs include pneumomediastinum and left-sided pneumothorax. With Boerhaave ruptures, pleural effusions are striking, particularly on the left, where it is often associated with left lower lobe consolidation. [8]

Other findings include hydropneumothorax, hydrothorax (usually unilateral), pneumomediastinal air along the inferior descending aorta, air in the left cardiovertebral angle of the diaphragm (V sign of Naclerio), subcutaneous emphysema in the neck, and delayed mediastinal widening caused by mediastinitis.

Other findings

Widening of the mediastinum is usually the result of inflammation or abscess formation. The extent of the widening and the configuration of the widening depend upon its cause. An important sign of mediastinitis secondary to esophageal perforation is the presence of air in the mediastinum. This air may be bubbly or streaky. Air may extend into the neck or the retroperitoneum. These findings are better depicted on CT scans than on radiographs. [9] If this injury is suspected, an esophagogram obtained with nonionic contrast material is recommended. The morbidity and mortality associated with delayed treatment of this injury are high. About 90% of esophagograms are positive in showing a leakage of contrast agent. [10]

Double-enhanced imaging

In a study by Cassel et al of the use of double-enhanced images of the lower esophagus, 10 abnormalities were detected in 22 patients, including a Mallory-Weiss tear. Only 6 abnormalities were demonstrated on single-contrast studies. Besides having a high success rate, this technique allows for repeat imaging and, according to the authors, can be easily incorporated into routine upper GI examinations. [11]

Computed Tomography

Esophageal perforations are serious, catastrophic events, regardless of the etiology. If the history or clinical symptoms are suggestive of esophageal perforation, contrast-enhanced esophagograms can be used to assess the condition for diagnosis; however, the clinical features may be atypical, and in such cases, a CT scan is performed early in the patient's workup.

CT has dramatically changed the imaging approach to the mediastinum, as it can depict precise cross-sectional mediastinal anatomic detail defining fat, water, and near–muscle density tissues. [12] Many causes of extraluminal air within the mediastinum, mediastinal fluid, and esophageal thickening are reported; these provide a potential for false-positive and false-negative diagnoses. CT findings should always be interpreted in light of the patient's clinical presentation. CT findings may include extraluminal air, periesophageal fluid, esophageal thickening, and extraluminal contrast. These findings may be the first indications of esophageal perforation. [13, 14, 15]

(See the CT images of esophageal tear below.)

Nonenhanced CT scan through the mid esophagus in a patient with esophageal perforation after upper GI endoscopy shows a false tract emanating from the esophagus (arrow).

Nonenhanced CT scan through the mid esophagus in a patient with esophageal perforation after upper GI endoscopy shows a false tract emanating from the esophagus (arrow).

Nonenhanced CT scan through the mid esophagus in a patient with esophageal perforation after upper GI endoscopy shows leakage of oral contrast material (blue arrow) and air in the posterior mediastinum (red arrow).

Nonenhanced CT scan through the mid esophagus in a patient with esophageal perforation after upper GI endoscopy shows leakage of oral contrast material (blue arrow) and air in the posterior mediastinum (red arrow).

Axial post-contrast CT images through the neck show a soft tissue mass in the upper esophagus. Note the air within the posterior high esophageal mass. A biopsy (not revealed) depicted a squamous cell carcinoma. The mass extends into the neck on the left, encasing the left external carotid artery.

Axial post-contrast CT images through the neck show a soft tissue mass in the upper esophagus. Note the air within the posterior high esophageal mass. A biopsy (not revealed) depicted a squamous cell carcinoma. The mass extends into the neck on the left, encasing the left external carotid artery.

CT findings of esophageal rupture include focal extraluminal air collections at the site of a tear and a hematoma of the mediastinal or esophageal wall. Occasionally, a tract at the site of the tear can be identified on CT scans. In the setting of severe blunt chest trauma, the esophagus can also be obstructed and entrapped by fracture-dislocations of the thoracic spine, as demonstrated on chest or thoracic spinal CT. The diagnosis of esophageal rupture is usually confirmed with a swallow study with nonionic oral contrast material. [1]

CT findings in esophageal tear/perforation can be summarized as follows:

-

Extraluminal air in the mediastinum or surrounding the esophagus is the most reliable sign and, when taken in conjunction with the clinical presentation, has a 92% accuracy.

-

Gas may appear as a single or multiple discrete collections, particularly with mediastinal abscess formation.

-

Air fluid levels may also be seen within mediastinal abscesses.

Other findings include obliteration of fat planes in the mediastinum resulting from inflammation, periesophageal/mediastinal fluid (92% accuracy), esophageal thickening, pleural effusions (usually unilateral), extravasation of oral contrast material into the periesophageal tissues, and a tract at the site of the tear (in rare cases). [12, 16]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography has not been used in the diagnosis of esophageal tears and perforations; however, transesophageal endosonography has been used to evaluate posterior mediastinitis, which is a known complication of esophageal tears.

In a study by Fritscher-Raven et al regarding the value of transesophageal endosonography with guided fine-needle aspiration in critically ill patients with suspected posterior mediastinitis, transesophageal endosonography depicted mediastinal lesions in 16 out of 18 patients (89%), and it was more accurate in supporting the diagnosis than CT scanning. The authors concluded that bedside transesophageal endosonography/fine-needle aspiration of posterior mediastinal lesions in critically ill patients was effective and noninvasive for detecting mediastinitis, and it provided material for identifying the etiologic agent. They further indicated that transesophageal endosonography is particularly useful in patients after an esophagectomy. [3]

-

This image was taken in a 36-year-old man presenting with hematemesis after an alcoholic binge. Endoscopy shows oozing blood from the base of a clot overlying a Mallory-Weiss tear (arrow).

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows a right-sided hydropneumothorax after an esophageal rupture.

-

A contrast-swallow study that shows leakage of contrast agent at the level of the carina (same patient as in previous image).

-

Water-soluble contrast study of the upper esophagus shows leakage of contrast material after instrumentation.

-

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in following image).

-

Cervical abscess following esophageal injury subsequent to endotracheal intubation. Note the increased soft tissue prevertebral space and air in the soft tissues (same patient as in previous image).

-

Nonenhanced CT scan through the mid esophagus in a patient with esophageal perforation after upper GI endoscopy shows a false tract emanating from the esophagus (arrow).

-

Nonenhanced CT scan through the mid esophagus in a patient with esophageal perforation after upper GI endoscopy shows leakage of oral contrast material (blue arrow) and air in the posterior mediastinum (red arrow).

-

Axial post-contrast CT images through the neck show a soft tissue mass in the upper esophagus. Note the air within the posterior high esophageal mass. A biopsy (not revealed) depicted a squamous cell carcinoma. The mass extends into the neck on the left, encasing the left external carotid artery.