Practice Essentials

Biliary cystadenoma (BCA) represents a rare benign cystic hepatic neoplasm that has premalignant potential. The tumor originates in the bile ducts and is lined by mucin-secreting columnar or cuboidal epithelium. Biliary cystadenoma can appear as a unilocular or multilocular cystic intrahepatic mass. The malignant counterpart is biliary cystadenocarcinoma (BCAC), which is believed to arise from the premalignant form.

Biliary cystadenomas constitute less than 5% of cystic lesions of the liver. Patients are typically middle-aged woman with abdominal pain, distention, and a palpable mass. Because it is difficult to differentiate a benign mass from a malignant biliary cystadenoma, the lesions should be completely resected. There are 2 types of biliary cystadenomas: those with and those without mesenchymal (ovarian-like) stroma. The ovarian-like stroma is thick, consists of compact spindle-shaped cells, supports the epithelium, and is often seen exclusively in women. Cystadenomas with mesenchymal stroma are considered premalignant with a good prognosis, and those without atroma transform to malignancy more often, with a poor prognosis. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

(The radiologic characteristics of cystademona are demonstrated in the images below.)

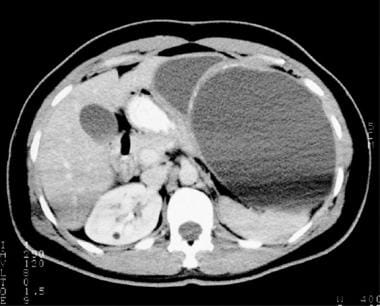

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in an elderly woman. The image demonstrates a large, well-defined, multiloculated, hypoattenuating lesion in the left hepatic lobe. The cystic lesion was lined by columnar epithelium, as observed at histologic evaluation; this finding was consistent with biliary cystadenoma.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in an elderly woman. The image demonstrates a large, well-defined, multiloculated, hypoattenuating lesion in the left hepatic lobe. The cystic lesion was lined by columnar epithelium, as observed at histologic evaluation; this finding was consistent with biliary cystadenoma.

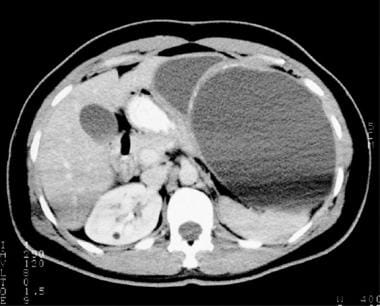

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a 37-year-old woman with a history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The image demonstrates a large, multiloculated, cystic lesion in the left hepatic lobe with fine peripheral calcifications. Aspiration revealed a cloudy grayish-brown fluid. Histologic analysis demonstrated the presence of small glands lined by columnar epithelium and dense cellular stroma of uniform spindle cells; these findings were consistent with hepatobiliary cystadenoma.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a 37-year-old woman with a history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The image demonstrates a large, multiloculated, cystic lesion in the left hepatic lobe with fine peripheral calcifications. Aspiration revealed a cloudy grayish-brown fluid. Histologic analysis demonstrated the presence of small glands lined by columnar epithelium and dense cellular stroma of uniform spindle cells; these findings were consistent with hepatobiliary cystadenoma.

Imaging modalities

Radiology plays an important role in the diagnosis of intrahepatic cystic lesions. The differential diagnosis for biliary cystadenoma includes hydatid cyst, simple cysts, liver abscesses, intraductal papillary mucinous tumor, and biliary cystadenocarcinomas. [2, 3, 4, 7]

Hepatic cystadenomas are often discovered incidentally on routine physical examination or on imaging studies, such as ultrasonography or CT scanning. Symptoms are nonspecific and include abdominal distention, abdominal pain, and abdominal mass. [8] Less frequently, nonspecific symptoms related to compression of a neighboring organ may be noted. Presenting symptoms depend on the size and the location of the lesion. [9]

Diagnostic imaging is an integral part of the patient evaluation for cystic lesions in the liver. Although the 3 primary imaging modalities are ultrasonography, CT scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasonography should be the initial screening modality. However, CT scanning and, occasionally, MRI may be needed to determine the exact location and extent of the disease. [10, 11, 12, 6]

In general, all 3 imaging modalities have inherent limitations. In published studies, CT scanning was less sensitive in correctly identifying septa within a cystic lesion. [13, 14, 15] Ultrasonography is more reliable in correctly diagnosing the degree of septation, which is a predominant feature of both cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas. Papillary projections can be seen with both CT scanning and ultrasonography.

MRI signal characteristics of biliary cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma are not specific for the disease. The cyst often appears hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, similar to other fluid-filled cystic lesions. Furthermore, depending on the fluid content of the cyst, the T1- and T2-signal characteristics can vary. [16, 7, 5]

Both biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma are slow growing; as a result, they can be difficult to distinguish from simple hepatic cysts, especially when the tumors are in the unilocular form. The diagnosis is often difficult because the clinical presentation is also similar to that of hepatic cysts. Moreover, other hepatic cystic lesions, including hydatid cysts and a number of metastatic tumors that undergo cystic degeneration, can mimic biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas. The radiographic appearances of benign and malignant cystic intrahepatic lesions overlap significantly.

Kovacs et al reported that the relationship of internal septations to the cyst wall may be used to differentiate hepatic cysts from biliary cystadenomas on ultrasound, based on the retrospective evaluation of 25 pathologically confirmed hepatic cystic lesions. In this sample, biliary cystadenomas were very highly associated with septations from a cyst wall without external indentation. [17]

Angiographic evaluation may reveal an avascular mass, as opposed to hepatocellular carcinoma or cystic metastasis, but it plays a limited role in the diagnosis of biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. As with other cystic lesions in the liver, displacement of blood vessels may be demonstrated.

Radiography

Plain radiographic results are nonspecific, and the images may show few or no findings. Possible findings include coarse curvilinear calcifications in the right upper abdominal quadrant and elevation of the right hemidiaphragm, if hepatomegaly or right pleural effusion is present.

Certain features of biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas may suggest a more aggressive lesion; however, radiographic distinction is difficult. Both tumors are multiloculated, hypoattenuating, and enhancing after the administration of contrast material. Generally, cystadenocarcinomas may exhibit coarse calcifications and mural nodules.

Computed Tomography

Cystadenomas appear as multiloculated, hypodense masses as large as 30 cm (see the images below). [18, 19] The mass wall is well defined and enhances with the administration of contrast material. The cystic mass demonstrates fluid attenuation (eg, mucin, blood, bile). Cystadenomas occasionally have fine septal calcifications, which may be seen during CT scanning.

Cystadenocarcinoma calcifications tend to be thick and coarse. Cystadenocarcinomas may demonstrate papillary projections into the lumen or mural nodules.

Biliary dilatation is uncommon except in the rare extrahepatic cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in an elderly woman. The image demonstrates a large, well-defined, multiloculated, hypoattenuating lesion in the left hepatic lobe. The cystic lesion was lined by columnar epithelium, as observed at histologic evaluation; this finding was consistent with biliary cystadenoma.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in an elderly woman. The image demonstrates a large, well-defined, multiloculated, hypoattenuating lesion in the left hepatic lobe. The cystic lesion was lined by columnar epithelium, as observed at histologic evaluation; this finding was consistent with biliary cystadenoma.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a 37-year-old woman with a history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The image demonstrates a large, multiloculated, cystic lesion in the left hepatic lobe with fine peripheral calcifications. Aspiration revealed a cloudy grayish-brown fluid. Histologic analysis demonstrated the presence of small glands lined by columnar epithelium and dense cellular stroma of uniform spindle cells; these findings were consistent with hepatobiliary cystadenoma.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a 37-year-old woman with a history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The image demonstrates a large, multiloculated, cystic lesion in the left hepatic lobe with fine peripheral calcifications. Aspiration revealed a cloudy grayish-brown fluid. Histologic analysis demonstrated the presence of small glands lined by columnar epithelium and dense cellular stroma of uniform spindle cells; these findings were consistent with hepatobiliary cystadenoma.

Degree of confidence

Differentiating biliary cystadenoma from cystadenocarcinoma with imaging criteria may not be possible in many patients. This concern, however, is considered to be less important therapeutically than academically, as treatments are similar in patients with either tumor because of the premalignant nature of biliary cystadenomas. However, cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas must be differentiated from other cystic liver lesions.

Congenital hepatic cysts can mimic cystadenomas or cystadenocarcinomas because all are cystic intrahepatic lesions that are filled with low-attenuating fluid. The clinical implication is important because the treatment options differ greatly among these conditions. Generally, biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas are solitary lesions, whereas congenital hepatic cysts tend to be multiple. However, the differentiation among these can be difficult because they are slow growing. Alternatively, large intrahepatic congenital cysts may be mistaken for premalignant cystadenoma or even malignant cystadenocarcinoma, especially if the congenital cyst is depicted as septate or complex on CT scans.

Liver abscesses and hydatid disease of the liver can present as septate or multiloculated cystic masses on CT scans. These infectious diseases can be evaluated with laboratory findings.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The diagnostic role of MRI is to better define the lesion, to verify the CT scan and ultrasonographic characteristics, and to exclude conditions that mimic these tumors, such as cystic hepatocellular carcinoma. [16]

MRI findings of biliary cystadenoma have been shown to correlate well with the gross pathologic findings. The mass is typically a fluid-containing multilocular cyst with homogeneous low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and homogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Depending on the content of the cystic fluid, T1- and T2-weighted images may demonstrate variable intermediate signal intensities.

As with CT scan examination, using MRI to differentiate biliary cystadenoma from cystadenocarcinoma is difficult in many patients, although MRIs may show septa better than CT scans. However, ultrasonography is the most sensitive of the 3 primary imaging modalities for detecting the presence and degree of septation. In addition, calcifications are poorly imaged with MRI; thus, calcification is not used as an MRI criterion for the diagnosis of biliary cystadenocarcinoma. Nonetheless, MRI can be helpful in differentiating cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas from other cystic liver lesions on the basis of several criteria.

Generally, inflammatory lesions tend to show a greater degree of wall enhancement on MRIs than on CT scans. Abscesses usually show increased rim enhancement, which has been described as caused by the degree of capillary permeability in the surrounding liver parenchyma. However, although the surrounding edema is not typically a helpful finding, because it occurs in both abscesses and cystadenocarcinomas, the presence of edema can help differentiate abscess formation from benign biliary cystadenoma, which tends not to form pericystic edema. In addition, the presence of air within a hepatic abscess on MRI is diagnostic for an air-forming organism and appears as a signal void. Air can also be recognized on CT scans, if present.

The most common cystic subtype of primary liver neoplasm is hepatocellular carcinoma. Chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C are the major risk factors for liver cirrhosis, which accounts for approximately 60-90% of all hepatocellular carcinomas. On CT scans or MRIs, signs of coexistent cirrhosis, such as ascites, macronodules, or hepatomegaly, help clinicians and radiologists differentiate cystic hepatocellular carcinoma from biliary cystadenocarcinoma.

Ultrasonography

The characteristic ultrasonographic finding for biliary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma is an anechoic mass with echogenic internal septations, as seen in the image below. Papillary projections into the cystic space may be seen.

Ultrasonograms in an elderly woman. The images demonstrate an intrahepatic cystic lesion that is anechoic, with papillary projections into the lumen, a characteristic finding in biliary cystadenoma. In this patient, ultrasonographic evaluation demonstrated more complex features, which helped to exclude a simple hepatic cyst.

Ultrasonograms in an elderly woman. The images demonstrate an intrahepatic cystic lesion that is anechoic, with papillary projections into the lumen, a characteristic finding in biliary cystadenoma. In this patient, ultrasonographic evaluation demonstrated more complex features, which helped to exclude a simple hepatic cyst.

A retrospective study by Dong et al analyzed contrast-enhanced ultrasound features in 23 patients with histologically identified biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. After injection of ultrasound contrast agents, nearly 80% of the lesions had a typical honeycomb enhancement pattern of the cystic wall, septa, or mural nodules. The authors also reported that hyperenhancement of the honeycomb septa during the arterial phase was more common in biliary cystadenoma, while hypoenhancement during the portal venous and late phases was more likely in biliary cystadenocarcinoma. [9]

Degree of confidence

Often, ultrasonography cannot be used as a reliable means for defining the exact anatomy or for determining the degree of disease involvement. These roles are better reserved for CT scanning and MRI; however, the differentiation of simple cysts from biliary cystadenomas or cystadenocarcinomas should almost always be possible on the basis of ultrasonographic and CT scan criteria.

On ultrasonograms, a congenital hepatic cyst can mimic any cystic hepatic lesion, particularly if the cyst is multiloculated. Generally, the presence of a multiloculated anechoic cyst, as depicted on ultrasonograms, warrants further investigation by CT scanning, as does a cystic lesion that appears to enlarge over time or that develops other signs of the malignant potential seen in biliary cystadenocarcinoma.

Liver abscesses and hydatid disease of the liver can present as septate or multiloculated cystic masses on sonograms. These infectious diseases can be evaluated with laboratory findings.

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in an elderly woman. The image demonstrates a large, well-defined, multiloculated, hypoattenuating lesion in the left hepatic lobe. The cystic lesion was lined by columnar epithelium, as observed at histologic evaluation; this finding was consistent with biliary cystadenoma.

-

Ultrasonograms in an elderly woman. The images demonstrate an intrahepatic cystic lesion that is anechoic, with papillary projections into the lumen, a characteristic finding in biliary cystadenoma. In this patient, ultrasonographic evaluation demonstrated more complex features, which helped to exclude a simple hepatic cyst.

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a 37-year-old woman with a history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The image demonstrates a large, multiloculated, cystic lesion in the left hepatic lobe with fine peripheral calcifications. Aspiration revealed a cloudy grayish-brown fluid. Histologic analysis demonstrated the presence of small glands lined by columnar epithelium and dense cellular stroma of uniform spindle cells; these findings were consistent with hepatobiliary cystadenoma.