Practice Essentials

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a rare multisystem autoimmune disease of unknown etiology characterized by necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis of the upper and lower respiratory tract, glomerulonephritis, and small-vessel vasculitis of variable degree. GPA is one of the antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitides (AAVs) and has a predilection for the upper and lower respiratory tracts and the kidneys. A key feature of GPA is the presence of ANCAs-cytoplasmic in approximately 90% of systemic forms and 50% of localized forms of the disease. The ANCA-associated vasulitides consist of 3 diseases: GPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). [1, 2, 3, 4]

The classic triad of GPA consists of involvement of the lungs, upper respiratory tract/sinuses, and kidneys. The limited form does not manifest as the full triad and presents with clinical findings largely isolated to the upper and lower respiratory tracts; it is not considered an organ- or life-threatening disease. Widespread GPA may include the prostate, spleen, skin, eyes, or peripheral nervous system. [5, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8]

Imaging modalities

Because most patients have respiratory symptoms, chest radiographs are usually obtained first. These may be followed by computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest for better delineation of the abnormalities. Radiographic findings are nonspecific and include pulmonary nodules, fixed pulmonary infiltrates, and pulmonary cavities.

There are no imaging diagnostic criteria for GPA. Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical manifestations, positive ANCA serology, and histologic evidence of necrotizing vasculitis, necrotizing glomerulonephritis, or granulomatous inflammation from a relevant organ biopsy, such as skin, lung, or kidney. [7] If the clinical findings are suggestive of GPA, further evaluation with biopsy or laboratory studies is required. [8, 9, 10]

The major limitation of radiographic techniques is the broad differential diagnosis of abnormalities in GPA. In addition, chest radiographic findings may be normal in as many as 20% of patients with the disease.

Lesions in GPA are gallium avid on nuclear medicine exams, as demonstrated in case reports. A negative gallium scan may be helpful in excluding active disease. [11]

Studies have shown that GPA is associated with increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake on positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). [4, 12, 10]

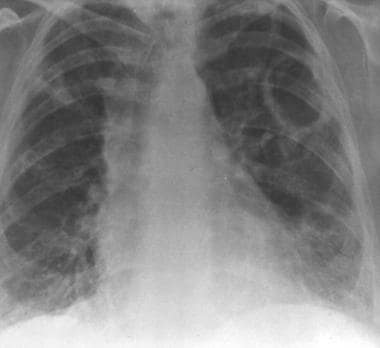

(See the image below.)

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a middle-aged man with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) shows heterogeneous airspace opacities which predominately involve the lower lobes and a focal ill-defined opacity in the right upper lobe. Findings are suggestive of pulmonary hemorrhage.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a middle-aged man with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) shows heterogeneous airspace opacities which predominately involve the lower lobes and a focal ill-defined opacity in the right upper lobe. Findings are suggestive of pulmonary hemorrhage.

Although the list of differential diagnoses and other problems is exceedingly broad and varied, the differential diagnosis can usually be limited by evaluating the radiographic findings in the context of the clinical history. Rheumatoid vasculitis (RV) is a major differential diagnosis. RV usually occurs in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients with longstanding disease. GPA lesions show necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis of small vessels, while the RV lesions mostly show leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). Other differential diagnoses include pyoderma gangrenosum, lymphoma, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and deep fungal infection.

Radiography

Pulmonary nodules are the most common chest radiographic manifestation of GPA; they occur in 40-70% of cases. Nodules may be solitary or multiple; they are cavitated in as many as 50% of patients with nodules. Both thick- and thin-walled cavities may be present. Their size varies, ranging from 1.5 to 10 cm, and the nodules may wax and wane over time. Pneumothorax in association with cavitary nodules and subpleural blebs has been reported. [13, 14, 15]

Airspace opacities are a second manifestation of GPA. Usually, these findings involve a localized region of consolidation that may occasionally show central necrosis that mimics a lung abscess. Frequently, this finding is the result of pulmonary hemorrhage, although pulmonary edema secondary to renal involvement may also occur. Over time, several of these opacities may evolve into thin-walled cavitary lesions. [13, 14, 15]

Other, less common pulmonary manifestations include atelectasis and reticular interstitial opacities. Tracheal-bronchial abnormalities are rarely noted on chest radiographs, although tracheal stenosis may occasionally be visualized. Mediastinal adenopathy and pleural abnormalities are uncommon (< 10% of cases) and should prompt consideration of other diagnoses. [13, 14, 15]

Because GPA is a rare disease, its appearance at the top of a differential diagnosis is unusual. Exceptions involve patients with sinusitis or renal disease and cavitary nodules or those with any of the above-mentioned radiographic findings and the appropriate clinical and laboratory findings. More often, radiographs are helpful in confirming the diagnosis and in assessing the extent of pulmonary involvement.

(See the images below.)

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a middle-aged man with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) shows heterogeneous airspace opacities which predominately involve the lower lobes and a focal ill-defined opacity in the right upper lobe. Findings are suggestive of pulmonary hemorrhage.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a middle-aged man with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) shows heterogeneous airspace opacities which predominately involve the lower lobes and a focal ill-defined opacity in the right upper lobe. Findings are suggestive of pulmonary hemorrhage.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Image obtained 4 months later in the same patient as in the previous image shows nearly complete resolution of lower lobe airspace disease with partial resolution of the right upper lobe opacity. A new cavity is present in the left upper lobe.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Image obtained 4 months later in the same patient as in the previous image shows nearly complete resolution of lower lobe airspace disease with partial resolution of the right upper lobe opacity. A new cavity is present in the left upper lobe.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Same patient as in the previous 2 images. This radiograph was obtained 1 year after the image immediately previous to this one. It shows that the left upper lobe cavity has enlarged without a change in wall thickness. Multiple new cavitary and noncavitary nodules are present in the right lung.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Same patient as in the previous 2 images. This radiograph was obtained 1 year after the image immediately previous to this one. It shows that the left upper lobe cavity has enlarged without a change in wall thickness. Multiple new cavitary and noncavitary nodules are present in the right lung.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Thick-walled right upper lobe cavity in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Thick-walled right upper lobe cavity in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is present as a single pulmonary mass. Chest radiograph shows a single right lower-lobe mass.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is present as a single pulmonary mass. Chest radiograph shows a single right lower-lobe mass.

Computed Tomography

The major value of CT scanning is in the further characterization of lesions found on chest radiography as well as in the depiction of unsuspected or radiographically occult abnormalities. Occasionally, CT scan findings are normal. As with chest radiographic findings, the predominant CT manifestations of GPA include pulmonary nodules with or without cavitation and airspace consolidation. [16]

(See the images below.)

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. CT scan shows a well-circumscribed right lower-lobe mass. Biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis which is consistent with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. CT scan shows a well-circumscribed right lower-lobe mass. Biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis which is consistent with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. CT image obtained with lung window settings shows a typical appearance of nodules in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Multiple ill-defined peripheral nodules have a halo with a ground-glass appearance. The halo is thought to represent adjacent pulmonary hemorrhage.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. CT image obtained with lung window settings shows a typical appearance of nodules in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Multiple ill-defined peripheral nodules have a halo with a ground-glass appearance. The halo is thought to represent adjacent pulmonary hemorrhage.

On CT, pulmonary nodules and masses range from 0.5 to 10 cm, and they are often cavitated. The lesions tend to be multiple and well defined, although the presence of more than 10 lesions is unusual. [17]

Airspace disease may include the following: (1) bilateral and diffuse disease caused by pulmonary hemorrhage, (2) scattered parenchymal disease with eventual coalescence of lesion, or (3) localized disease with ill-defined margins and air bronchograms or central cavitation. In the last case, the lesions may be surrounded by a halo of ground-glass opacity, which is the expression of alveolar hemorrhage.

Interstitial abnormalities are often present in GPA. They include interlobular septal thickening, parenchymal bands, and bronchial wall thickening. High-resolution CT (HRCT) scanning may be helpful in better defining these lesions. Pleural thickening, pleural effusion, and adenopathy may be present, but they are not usually associated with GPA.

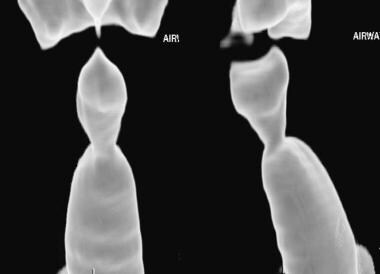

Tracheobronchial abnormalities are better evaluated with CT than with other modalities. Although as many as 60% of patients with GPA have tracheobronchial abnormalities, no good data about the sensitivity and specificity of CT are available. In cases of suspected tracheobronchial involvement, thin, overlapping, axial sections with 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional reformations may provide better delineation of the length and degree of stenosis. These are particularly helpful when a tight stricture precludes the passage of a bronchoscope.

(See the image below.)

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. A three-dimensional shaded-surface display of the trachea shows eccentric narrowing of the subglottic trachea in this patient with airway involvement from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. A three-dimensional shaded-surface display of the trachea shows eccentric narrowing of the subglottic trachea in this patient with airway involvement from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

Although nodules occur more frequently in patients with active disease and although parenchymal bands are more often seen in patients with quiescent disease, findings at various disease stages overlap considerably. Therefore, CT scan findings cannot be used to determine disease activity. CT scanning has greater utility in determining the response to corticosteroid and cytotoxic drug therapy. An increase in the size or number of parenchymal abnormalities suggests relapse, whereas decreasing nodule size, thickening of cavity walls, and increasing spiculation of lesions have all been described as indicative of improvement.

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is a common cause of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), representing 45% of the cases. DAH is defined by the presence of hemoptysis, diffuse alveolar infiltrates, and a decreased hematocrit level. HRCT features consist of bilateral ground-glass opacities and consolidations that are usually prominent in the perihilar areas, with a relative sparing of the subpleural pulmonary parenchyma, pulmonary apices, and costophrenic angles. The crazy-paving pattern, which is characterized by smooth and regular interlobular septal thickening associated with ground-glass opacification, may be seen days later in an acute episode of hemorrhage. [17]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The prevalence of myocardial involvement varies from 6 to 86% in GPA patients. [18] Patients with myocardial involvement may have no symptoms or nonspecific symptoms, a normal ECG, and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), but they may nevertheless face life-threatening arrhythmias or end-stage heart failure during the course of the disease. MRI may be useful in documenting myocardial abnormalities. [19]

Lesions may be diffuse or focal, involving the midventricular wall; they are not typical of patterns associated with myocardial ischemia. Cardiac MRI findings overlap with those of other nonischemic myocardial diseases, such as sarcoidosis and amyloidosis. MRI of the brain and/or spine should be considered in cases of extrapulmonary disease that potentially involves the central nervous system. [20]

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a middle-aged man with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) shows heterogeneous airspace opacities which predominately involve the lower lobes and a focal ill-defined opacity in the right upper lobe. Findings are suggestive of pulmonary hemorrhage.

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Image obtained 4 months later in the same patient as in the previous image shows nearly complete resolution of lower lobe airspace disease with partial resolution of the right upper lobe opacity. A new cavity is present in the left upper lobe.

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Same patient as in the previous 2 images. This radiograph was obtained 1 year after the image immediately previous to this one. It shows that the left upper lobe cavity has enlarged without a change in wall thickness. Multiple new cavitary and noncavitary nodules are present in the right lung.

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Thick-walled right upper lobe cavity in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Cut surface of a gross pathologic specimen that shows a thick-walled cavity with internal hemorrhage and necrosis. Courtesy of Russell Harley, MD.

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is present as a single pulmonary mass. Chest radiograph shows a single right lower-lobe mass.

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. CT scan shows a well-circumscribed right lower-lobe mass. Biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis which is consistent with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. CT image obtained with lung window settings shows a typical appearance of nodules in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Multiple ill-defined peripheral nodules have a halo with a ground-glass appearance. The halo is thought to represent adjacent pulmonary hemorrhage.

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), thoracic. A three-dimensional shaded-surface display of the trachea shows eccentric narrowing of the subglottic trachea in this patient with airway involvement from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA).