Practice Essentials

Urethral injury is a relatively rare medical condition, accounting for less than 1% of all emergency department visits in the United States. Injury patterns vary and encompass urethral crush, bruising, laceration, and transection. Urethral injuries are never life-threatening, but if left untreated, they can cause significant morbidity. Although most injuries are iatrogenic, traumatic etiologies often caused by high-energy mechanisms certainly do carry mortality threats. Extent of injury and anatomic location are formative in the development of a management plan. [1]

Sources suggest that up to 10% of patients involved in significant blunt or penetrating trauma have a urethral injury. Among these, young males, ages 11 to 25, present most commonly. Men are nearly 10 times more likely to experience a urethral injury than women. Anatomically, females are at lower risk because of their comparatively shorter and more mobile urethra, as well as the mobility of the uterus. Despite this gender advantage, the incidence of urethral injury in females with pelvic fracture is reportedly as high as 6%. [1, 2, 3]

Injury to the urethra is usually associated with severe pelvic trauma in males. Such an injury can have enduring consequences that include stricture, impotence, and incontinence. [4] Urethral injuries constitute 4% of urologic trauma injuries. In cases of pelvic fracture, urethral injury may be present in up to 25% of men and 4.6% of women. Presentation may include blood at the urethral meatus, suprapubic fullness, and urinary retention. [5, 6, 7]

Diagnosis of urethral trauma should be investigated in the presence of pelvic fracture, straddle injury, penetrating trauma in the vicinity of the urethra, or penile fracture. [4, 8, 9, 10, 11] Although no findings are specific for urethral trauma, many suggest its presence. Findings can include blood at the urethral meatus, gross hematuria, inability to spontaneously void, and a high-riding prostate on rectal examination. [8, 12, 13, 14]

For many patients with urethral injury, extravasation of blood contained within different fascial planes is present. On examination, patients with injury to the urethra distal to the urogenital diaphragm and not contained by the Buck fascia typically have a butterfly hematoma, which forms as blood collects in the superficial perineum. [15] Scrotal enlargement is common with this injury, as extravasated fluids are bound only by Colles fascia. For patients with anterior urethral trauma with extravasation confined by the Buck fascia, edema and ecchymosis of the penile shaft are common. [12] In some cases, hematoma is not seen until at least an hour after injury. [8]

Urethral injuries can commonly be classified as anterior or posterior injuries. With some exceptions, anterior injuries involve a crushing mechanism, whereas posterior injuries involve shearing forces. Injury to the anterior urethra is more common in motor vehicle trauma, straddle injury, and blunt/penetrating trauma, whereas pelvic fractures and iatrogenic etiologies are more consistent with injury to the posterior urethra. [1]

The urotrauma guidelines provided by the American Urological Association (AUA) include appropriate methods of evaluation and management of genitourinary injuries. Guideline statements pertaining specifically to urethral trauma include the following [16] :

-

Clinicians should perform retrograde urethrography in patients with blood at the urethral meatus after pelvic trauma.

-

Clinicians should establish prompt urinary drainage in patients with pelvic fracture associated with urethral injury.

-

Clinicians should perform percutaneous or open suprapubic tube placement as preferred initial management for most pelvic fracture urethral injury (PFUI) cases.

-

Surgeons may place suprapubic tubes (SPTs) in patients undergoing open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) for pelvic fracture.

-

Clinicians may perform primary realignment (PR) in hemodynamically stable patients with pelvic fracture–associated urethral injury.

-

Clinicians should monitor patients for complications (eg, stricture formation, erectile dysfunction, incontinence) for at least 1 year following urethral injury.

-

Surgeons should perform prompt surgical repair in patients with uncomplicated penetrating trauma of the anterior urethra.

-

Clinicians should establish prompt urinary drainage in patients with straddle injury to the anterior urethra.

Imaging modalities

If any of the clinical findings listed above are present, the possibility of urethral trauma should be properly investigated by retrograde urethrography (RUG). [8, 9, 13] This should always be done prior to insertion of a urethral catheter.

Indications for urethral imaging include an unstable pelvis, a penile fracture, and significant perineal hematoma after straddle injury. Cystourethroscopy should be considered for evaluation of the bladder neck in women because injury to the bladder neck can result in urinary incontinence. [5, 6, 7]

In cases of delayed urethral repair, repeat imaging with RUG and voiding cystourethrography is necessary to help characterize the length and the location of the defect. If visualization of the bladder neck is poor, flexible cystoscopy through the suprapubic site can be used to gain better visualization. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can further characterize the stricture; findings can be used to estimate the length of the defect, the degree of prostatic misalignment, and the density of scar tissue [5, 6, 7]

For most patients with widespread acute trauma, computed tomography (CT) scanning is performed as an initial diagnostic tool. [17, 18] However, CT is not traditionally used for diagnosing urethral trauma. Research indicates that CT scanning may be useful as an initial screen for urethral injuries. [17, 19, 20]

In the past, diagnostic catheterization was used to check for urethral disruption. However, this has been universally dismissed as an acceptable diagnostic tool. [8] A urethral catheter risks converting a partial urethral tear into complete urethral disruption; this can increase the extent of hemorrhage, and it increases the possibility of contaminating a sterile hematoma. [12] If, however, a urethral catheter is properly in place before evaluation for urethral trauma, it should not be removed so urethrography can be performed. In such cases, a pericatheter urethrogram may be obtained.

After urethral trauma has been diagnosed, management and repair can be planned, possibly with the aid of imaging modalities such as MRI and ultrasonography. MRI has some utility in planning the surgical approach for posterior urethral disruption, and ultrasonography has been used at times to facilitate repair of urethral trauma. [21, 22, 23, 24, 25]

(See the images below.)

Urethra, trauma. Normal retrograde urethrogram. Pericatheter retrograde urethrogram is negative for urethral trauma and shows continuous filling of contrast material through the extent of the urethra and into the bladder without extravasation.

Urethra, trauma. Normal retrograde urethrogram. Pericatheter retrograde urethrogram is negative for urethral trauma and shows continuous filling of contrast material through the extent of the urethra and into the bladder without extravasation.

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type I urethral injury with minimal stretching and slight luminal irregularity of the posterior urethra. No extravasation of contrast material is present.

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type I urethral injury with minimal stretching and slight luminal irregularity of the posterior urethra. No extravasation of contrast material is present.

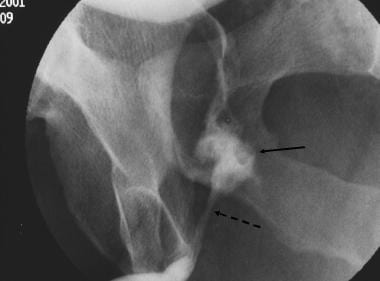

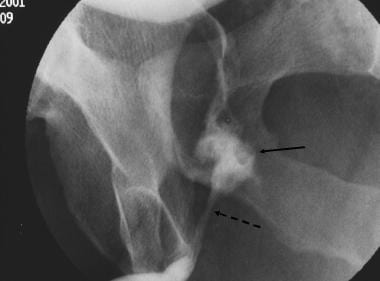

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a less common type II urethral disruption. Extravasation of contrast material (solid arrow) from the posterior urethra is seen superior to an intact urogenital diaphragm (dashed arrow).

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a less common type II urethral disruption. Extravasation of contrast material (solid arrow) from the posterior urethra is seen superior to an intact urogenital diaphragm (dashed arrow).

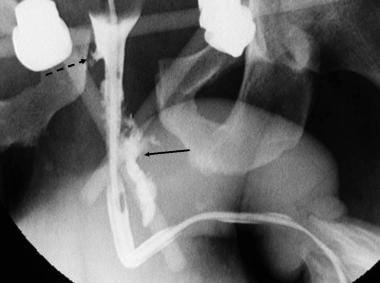

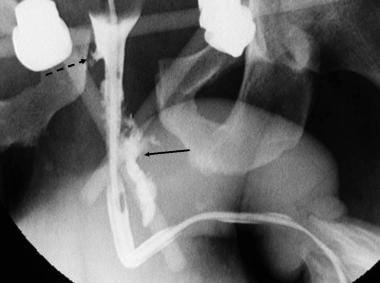

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type III urethral tear at the urogenital diaphragm (solid arrow) and a type IV urethral disruption at the bladder neck (dashed arrow).

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type III urethral tear at the urogenital diaphragm (solid arrow) and a type IV urethral disruption at the bladder neck (dashed arrow).

Urethra, trauma. Straddle injury. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type V urethral injury with extravasation of contrast material from the distal bulbous urethra.

Urethra, trauma. Straddle injury. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type V urethral injury with extravasation of contrast material from the distal bulbous urethra.

Limitations of techniques

Although RUG provides clinically valuable information regarding the presence, location, and severity of urethral extravasation, it provides limited information about details of surrounding soft tissue damage. Furthermore, imaging of the proximal urethra can occasionally be inadequate. This is usually caused by subpar contrast agent filling the proximal urethra or by gross extravasation of contrast blocking visualization of the proximal urethra. [23]

In contrast, MRI has proven clinical utility in defining damage to soft tissue neighboring the urethral trauma. However, MRI should not be used alone to investigate urethral extravasation or to define urethral trauma as partial or complete. [22, 23]

Radiography

The standard imaging method used to diagnose urethral trauma is retrograde urethrography (RUG). [8, 13] Although various techniques have been described to implement RUG, the most common utilizes a Foley catheter. [15, 24] With this method, the patient is ideally positioned for imaging at an approximate 45° oblique angle with the penis stretched so that the meatus points cephalad. This produces a C configuration from the bladder level to the meatus tip. If the penile shaft points caudad, the femur may obscure the opacified urethra.

For some patients with multiple injuries, this position is unattainable. In these cases, patients should be supine with the penis stretched perpendicular to the leg. When the image is obtained in this anteroposterior projection, however, the urethra can appear foreshortened, allowing for possible errors in interpretation of extravasation. [10, 12, 15]

The Foley catheter is then placed inside the urethra with the balloon inflated in the fossa navicularis. Approximately 20-30 mL of 30% contrast material is injected into the urethra, with exposure during active injection of the last few milliliters of contrast. Obtaining the image during injection allows for maximum filling of deeper bulbar, membranous, and prostatic urethral sections. [9, 12]

(See the image below.)

Urethra, trauma. Normal retrograde urethrogram. Pericatheter retrograde urethrogram is negative for urethral trauma and shows continuous filling of contrast material through the extent of the urethra and into the bladder without extravasation.

Urethra, trauma. Normal retrograde urethrogram. Pericatheter retrograde urethrogram is negative for urethral trauma and shows continuous filling of contrast material through the extent of the urethra and into the bladder without extravasation.

In the most ideal conditions, the entire procedure should be performed under fluoroscopic control; however, in the emergent environment, this is often impossible.

Classification of RUG findings

The best accepted and most unified classification of RUG findings for urethral injury is the Goldman classification, with its foundation in the earlier system developed by Colapinto and McCallum. [26, 27] The Goldman classification of urethral trauma is defined entirely on anatomic findings of the injury—not on its mechanism. This system defines 5 major types of urethral injury, as seen in RUG.

Type I urethral injury results when the puboprostatic ligament is ruptured and the prostate is allowed to move superiorly. The urethra remains intact and is severely stretched only by movement of the prostate. No extravasation of contrast material is seen with radiography, and continuity with the bladder is maintained. True cases of type I urethral injury are uncommon. [13]

(See the image below.)

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type I urethral injury with minimal stretching and slight luminal irregularity of the posterior urethra. No extravasation of contrast material is present.

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type I urethral injury with minimal stretching and slight luminal irregularity of the posterior urethra. No extravasation of contrast material is present.

Type II urethral trauma is the classically described posterior urethral injury in which the urethra is torn superior to the urogenital diaphragm. With such an injury, contrast agent extravasation is seen within the extraperitoneal pelvis, but contrast material is not present within the perineum. Here, the urogenital diaphragm is intact, preventing the spread of contrast material inferiorly. This type is seen in approximately 15% of urethral trauma cases resulting from pelvic crush injury. [13]

(See the image below.)

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a less common type II urethral disruption. Extravasation of contrast material (solid arrow) from the posterior urethra is seen superior to an intact urogenital diaphragm (dashed arrow).

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a less common type II urethral disruption. Extravasation of contrast material (solid arrow) from the posterior urethra is seen superior to an intact urogenital diaphragm (dashed arrow).

The most common type of urethral trauma has proved to be type III urethral injury. [13, 27] Type III urethral injury, similar to type II, shows disruption above the urogenital diaphragm. Unlike type II, this injury extends through the urogenital diaphragm and includes the proximal bulbous urethra. When this injury occurs, extravasation can be seen within the extraperitoneal pelvis and within the perineum.

(See the image below.)

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type III urethral injury. Extravasation is located both in the extraperitoneal pelvis and in the perineum (above and below the urogenital diaphragm).

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type III urethral injury. Extravasation is located both in the extraperitoneal pelvis and in the perineum (above and below the urogenital diaphragm).

The amount of contrast material found above or below the urogenital diaphragm depends on the exact location of the injury and the degree of disruption to the perineal membrane. [13]

Some investigators believe that type I, II, and III urethral disruptions may be seen as the same mechanism of trauma, with varying degrees of severity. [26] Indeed, at least 1 case of delayed rupture of type I urethral trauma has been reported. [28]

Type II or III urethral injury can be further classified as a partial or complete urethral tear. [27] With RUG, partial tears are diagnosed when extravasation of contrast material occurs with contrast material within the bladder. Complete tears are diagnosed when extravasation is present and no contrast agent is present in the bladder or in the proximal torn end of the urethra. The relative frequency of partial tears versus complete tears is highly variable in the literature, and no reason for this variance is known. [13]

Type IV urethral trauma can occur as a tear to the bladder neck that extends into the proximal urethra. Contrast agent extravasation is seen in the extraperitoneal pelvis around the proximal urethra. Such injuries can damage the internal urethral sphincter, resulting in incontinence. [27] Proper diagnosis is essential to ensure adequate patient care.

(See the image below.)

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type III urethral tear at the urogenital diaphragm (solid arrow) and a type IV urethral disruption at the bladder neck (dashed arrow).

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type III urethral tear at the urogenital diaphragm (solid arrow) and a type IV urethral disruption at the bladder neck (dashed arrow).

A related injury, as described in the Goldman classification, is type IVA. This is not a urethral injury, but it can easily be mistaken for a proximal urethral tear. In this case, the base of the bladder is disrupted, with periurethral extravasation of contrast agent. Resulting radiographs can easily mimic those of a true type IV urethral trauma. Distinguishing the 2 conditions is important because type IV injury is typically treated surgically but type IVA injury is not. [27] Dynamic RUG under fluoroscopic control facilitates differentiation.

Type V urethral trauma describes all cases that are isolated to the anterior urethra. Such an injury occurs distal to the urogenital diaphragm and is often associated with perineal crush or straddle injury. [15] The resulting urethral injury is usually a partial tear of the bulbous urethra, although complete tears can occur.

(See the image below.)

Urethra, trauma. Straddle injury. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type V urethral injury with extravasation of contrast material from the distal bulbous urethra.

Urethra, trauma. Straddle injury. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type V urethral injury with extravasation of contrast material from the distal bulbous urethra.

In this case, contrast agent extravasation occurs inferior to the urogenital diaphragm. If the Buck fascia remains intact, extravasation is limited to its confines (ie, the penile shaft). If the Buck fascia is disrupted, contrast material is contained within the limits of Colles fascia. [12, 15] In this case, contrast agent might be found in the lower abdomen and in the scrotum. [12]

Under certain circumstances, all clinical signs of urethral disruption may be present but contrast extravasation may be completely absent. In such a case, urethral contusion is often diagnosed. [15]

Degree of confidence

Specific degrees of confidence for diagnosing male urethral trauma by RUG are not documented.

With regard to females, opinions about the diagnostic dependability of urethrography are conflicting, and some believe that diagnosis should be made with urethroscopy.

As discussed above, type IV urethral injuries involving the proximal urethra can be radiologically indistinguishable from type IVA injuries that do not involve the urethra. Careful evaluation is necessary to distinguish these 2 injuries.

Similarly, reflux of contrast agent into Cowper ducts, which connect to the bulbous urethra, should not be confused with extravasation of the anterior urethra. [12]

Some investigators have questioned the accuracy of RUG in distinguishing partial and complete urethral tears. They have suggested that contrast material proximal to a partial rupture could be prevented by spasm of the external urethral sphincter. [8]

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) findings of urinary bladder and urethral injury are usually subtle. Retrograde fluoroscopic/CT cystography and urethrography remain the mainstay imaging techniques for complete evaluation, diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of patients with these traumatic injuries. [29]

Despite prevalent use of CT scanning as the initial screening modality for general acute trauma, the literature has historically described few applications of CT in diagnosing urethral injury. [30]

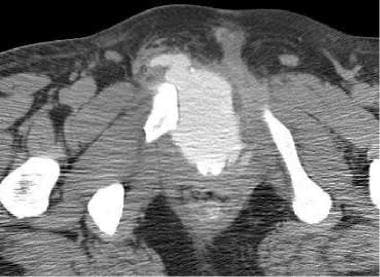

(See the images below.)

Urethra, trauma. CT scan shows extravasation of contrast material in the pelvic floor after complete disruption of the bladder base and the posterior urethra.

Urethra, trauma. CT scan shows extravasation of contrast material in the pelvic floor after complete disruption of the bladder base and the posterior urethra.

Urethra, trauma. CT scan shows contrast material in the perineum (same patient as in the previous image). This patient had extensive trauma to the bladder with injury extending to the membranous urethra.

Urethra, trauma. CT scan shows contrast material in the perineum (same patient as in the previous image). This patient had extensive trauma to the bladder with injury extending to the membranous urethra.

CT scan shows fluid and a slight presence of contrast material in the perineum; this is indicative of a urethral tear. Retrograde urethrography should be used to confirm the location of a urethral injury.

CT scan shows fluid and a slight presence of contrast material in the perineum; this is indicative of a urethral tear. Retrograde urethrography should be used to confirm the location of a urethral injury.

Because many patients with generalized trauma undergo CT before specific evaluation for urethral trauma, CT might serve as an initial screening examination for such injuries. No test supersedes RUG for confirmation of urethral trauma, [17, 18] but CT might help to exclude unnecessary RUG. Such a screening would require a thorough understanding of the relevant and intricate pelvic anatomy.

Some advocate performing CT retrograde urethrography (CT-RUG) in patients scheduled for CT of the pelvis for other indications and with high suspicion of urethral injury. CT-RUG can be performed with contrast that is more concentrated (eg, 40 mL of 60% contrast in 500 mL saline) than that typically used for CT cystography, to help distinguish extravasated contrast from vascular or bladder contrast extravasation. [31]

CT-RUG may also be useful for preoperative evaluation of patients with complex urethral injuries. [32]

Degree of confidence

Because few studies have been conducted to evaluate the accuracy of CT in identifying urethral trauma, further investigation is necessary for a well-defined degree of confidence.

CT cystography and conventional retrograde urethrography are effective tools for identifying injuries to the lower urinary tract; they play a crucial role in patient care and prognosis. [33]

CT is the test of choice for assessment of the intra-abdominal urinary system, including kidneys, ureters, and bladder. In many cases of blunt traumatic injury, CT will be ordered, but this does not replace the need for retrograde urethrography because CT fails to adequately evaluate the penile urethra. [1]

False-positive and false-negative results have not been thoroughly studied. It has been suggested that the presence of a Foley catheter in the urethra can produce false-negative findings for urethral trauma on CT studies. [18]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Traditionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has not been used as an initial diagnostic tool for urethral traumatic injuries; nevertheless, some researchers have explored the advantage of using MRI as a preparatory tool when surgical repair of urethral disruption is planned. [23, 26, 34, 35, 2]

Urethrography is the most commonly used preoperative evaluation; however, with this technique, information on prostatic displacement and on the degree of scarring can be limited. Further, the exact length of the urethral defect can be inaccurately determined when the prostatic urethra is not optimally filled with contrast material. [23, 26]

MRI has shown positive results in evaluating anterior-posterior, superior-inferior, and lateral displacement of the prostate; the degree of scar tissue around a urethral defect; and the precise length of a posterior urethral defect. Because of its superiority in defining local disruption to adjacent tissues, MRI in combination with RUG can be an important tool in evaluating urethral trauma for management. [36]

Altough RUG and voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) are the cornerstone of urethral imaging, MRI has been shown to be a useful adjunct, particularly for the staging of suspected urethral neoplasm, visualization of complex posterior urethral fistulas, and problem solving for indeterminate findings on RUG. [36]

MRI has been increasingly used as an adjunct after ultrasonography for penile disorders and provides cross-sectional imaging for assessment of urethra and periurethral disease. Advantages that have been noted for MRI of the penis and urethra include high soft tissue contrast resolution for assessing critical structures such as the tunica albuginea or walls of the urethra; a larger field of view; and demonstration of proteinaceous material and varying ages of blood products. [37]

Male pelvic fracture urethral injury can be a urologic challenge and can be associated with sequelae such as urethral gap, erectile dysfunction, and urinary incontinence. Antegrade and retrograde urethrography is the considered the preferred preoperative evaluation, but it cannot accurately assess the urethral gap length, the degree of lateral prostatic displacement, the anatomic relationship of the urethra with its surrounding structures, or periurethral problems such as minor fistulae or cavitation. As a result MRI has emerged as an adjunctive noninvasive, multiplanar, high-resolution modality to evaluate pelvic fracture urethral injury because of its excellent soft tissue contrast and because it can clearly show the urethra and periurethral tissues without the need for radiation. [3]

Use of MRI is theoretically attractive but is often logistically challenging. Some have advocated its use among children with a urethral injury when advanced imaging is warranted and this approach is not unreasonable. [1]

Ultrasonography

Similar to MRI and CT, ultrasonography alone has not proved to be adequate and is not typically used for the primary diagnosis of urethral trauma. [24] It has been suggested that ultrasonography can be used to define the extent of urethral damage in certain cases and to prepare the patient for surgical repair. [21, 38]

High-frequency probes used in sonourethrography provide high spatial resolution; therefore, details of urethral anatomy can be studied after a saline solution is injected. This saline solution technique uses a Foley catheter in a similar manner as described for RUG to promote distention of the urethra. The presence of saline in the urethra produces high contrast relative to the urethral mucosa. Thus, this technique allows accurate visualization of the urethral wall and of the urethral lumen. [25]

A limited number of reports have described the use of sonourethrography. Such cases include sonography used for diagnosis of urethral trauma associated with penile fracture and for evaluation of anterior urethral trauma prior to delayed urethroplasty. Sonourethrography has been shown to accurately depict trauma to soft tissues surrounding the urethra such as the tunica albuginea. [21] Investigators have shown that sonourethrography can more accurately measure stricture length when compared to RUG. [25] This information could prove useful for planning surgical repair in specific cases.

Investigators have suggested that sonography is better than RUG for revealing hematoma size and extent of fluid extravasation. [25]

-

Urethra, trauma. Normal retrograde urethrogram. Pericatheter retrograde urethrogram is negative for urethral trauma and shows continuous filling of contrast material through the extent of the urethra and into the bladder without extravasation.

-

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type I urethral injury with minimal stretching and slight luminal irregularity of the posterior urethra. No extravasation of contrast material is present.

-

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a less common type II urethral disruption. Extravasation of contrast material (solid arrow) from the posterior urethra is seen superior to an intact urogenital diaphragm (dashed arrow).

-

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type III urethral injury. Extravasation is located both in the extraperitoneal pelvis and in the perineum (above and below the urogenital diaphragm).

-

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a type III urethral tear at the urogenital diaphragm (solid arrow) and a type IV urethral disruption at the bladder neck (dashed arrow).

-

Urethra, trauma. Straddle injury. Retrograde urethrogram shows a type V urethral injury with extravasation of contrast material from the distal bulbous urethra.

-

Urethra, trauma. CT scan shows extravasation of contrast material in the pelvic floor after complete disruption of the bladder base and the posterior urethra.

-

Urethra, trauma. CT scan shows contrast material in the perineum (same patient as in the previous image). This patient had extensive trauma to the bladder with injury extending to the membranous urethra.

-

Urethra, trauma. After delayed repair for urethral trauma, this patient remained incontinent. Retrograde urethrogram confirms lack of constriction at the internal and external urethral sphincters.

-

Urethra, trauma. Retrograde urethrogram reveals a tight stricture - a common morbidity of urethral injuries treated with delayed repair.

-

Urethra, trauma. Cystogram reveals stricture of the urethra in a patient treated with delayed repair (same patient as in the previous image). The cystogram and the retrograde urethrogram together help to define the length of the stricture.

-

CT scan shows fluid and a slight presence of contrast material in the perineum; this is indicative of a urethral tear. Retrograde urethrography should be used to confirm the location of a urethral injury.