Practice Essentials

After the lungs, the genitourinary tract is the most common site of tuberculosis (see the image below). The infection almost always affects the kidneys during the primary exposure to infection but does not present clinically. The spread of infection to the kidneys from the lungs, bone, or GI tract is usually hematogenous. The true incidence of renal tuberculosis may be underestimated, because radiologic findings may be absent, and diagnosis is made by urine culture. Genital tuberculosis is usually secondary to renal tuberculous infection. All imaging findings may be normal in patients with early genitourinary tuberculosis (GUTB). Intravenous urography (IVU) remains the primary modality for identification of renal, ureteric, and bladder tuberculosis, but findings of urinary tuberculosis are also detectable on ultrasonography, CT scanning, or MRI. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] The role of imaging is to localize the site of infection, identify the extent and effect of the disease, plan treatment, and monitor the response to treatment. [9, 10]

Multidetector CT urography (MDCTU) has improved the assessment of renal and urinary tract lesions with the use of reformatted images, such as multiplanar reconstruction and maximum intensity projection. [11] In a study of the literature from 1997 to 2017, Mthalane et al found that MDCT can reproduce images comparable to those of intravenous excretory urography for renal tuberculosis, along with being able to better assess the renal parenchyma and surrounding spaces. [12]

GUTB is most commonly caused by Mycobacteriumtuberculosis and composes 20% of all forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. From 2 to 20% of individuals can develop genitourinary tuberculosis 5 to 25 years after having pulmonary tuberculosis. Renal and urologic tuberculosis most commonly involves the renal pelvis, calyces, ureter, and bladder; it less commonly involves the renal parenchyma. Genital tuberculosis involves the epididymis, testis, urethra, and prostate in males and the fallopian tubes, endometrium, and ovaries in females. [13, 14, 15, 16]

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a woman with renal tuberculosis shows calcification of varying patterns (curvilinear, amorphous, speckled).

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a woman with renal tuberculosis shows calcification of varying patterns (curvilinear, amorphous, speckled).

Renal involvement may be indolent, with a latency period of more than 20 years after the primary infection to the appearance of urinary tract symptoms of hematuria and stone disease. In patients with renal tuberculosis, treatment involves antitubercular drugs, with surgical excision as an adjunct to antitubercular therapy. The urine can be free of bacteria in less than 72 hours, but anatomic changes can progress as part of the healing process. Females with genital tuberculosis may present with infertility, menstrual disorders, and pain. Pregnancy is unusual in the presence of genital tuberculosis. When pregnancy occurs, spontaneous abortion or ectopic pregnancy usually results. Because of the lack of clinical features, diagnosis of genital tuberculosis may be difficult (see the images below).

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows an irregular cavity at the upper pole calyx of the right kidney. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the liver, spleen, and right adrenal gland due to calcified tuberculous granuloma.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows an irregular cavity at the upper pole calyx of the right kidney. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the liver, spleen, and right adrenal gland due to calcified tuberculous granuloma.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lobar calcification in a large destroyed right kidney in a patient with renal tuberculosis. Note the involvement of the right ureter.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lobar calcification in a large destroyed right kidney in a patient with renal tuberculosis. Note the involvement of the right ureter.

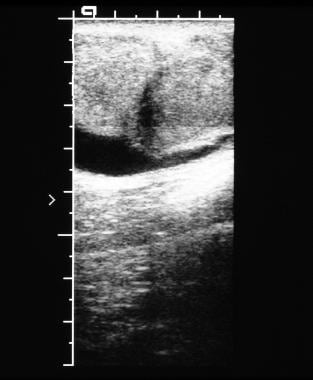

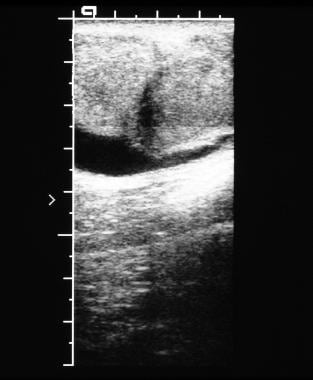

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the scrotum in a young male patient shows left epididymo-orchitis resulting from tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the scrotum in a young male patient shows left epididymo-orchitis resulting from tuberculosis.

The incidence of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis has increased since the late 20th century, primarily because of AIDS and the development of drug-resistant strains of Mycobacteriumtuberculosis. Diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis may be challenging because of its clinical and radiologic spectra and because it can mimic many other disease entities. [17] Therefore, to allow early diagnosis and timely management, a high index of clinical suspicion is required, as is familiarity with the spectra of imaging findings. Miliary tuberculosis is the disseminated form of tuberculosis and is potentially fatal. Diagnosis is often delayed because symptoms are typically nonspecific or absent, and misdiagnosis is common. [18, 19, 20, 21, 22]

Tuberculosis can affect any organ within the abdomen and may mimic a variety of inflammatory or neoplastic disorders. [6, 23, 18, 24] The abdominal lymph nodes, genitourinary tract, peritoneal cavity, and gastrointestinal tract are most commonly involved. The liver, spleen, biliary tract, pancreas, and adrenals are rarely affected but are more likely in HIV-seropositive patients and miliary tuberculosis. Involvement of the latter organs should raise the possibility of HIV-seropositive abdominal tuberculosis, thus alerting the radiologist to consider abdominal tuberculosis in the correct clinical setting to ensure timely diagnosis and enable appropriate treatment. [23]

Preferred examination

While intravenous urography (IVU) remains the primary imaging modality for patients with renal, ureteric, and bladder tuberculosis, findings of urinary tuberculosis are also detectable on ultrasonography, computed tomography scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging. [1, 2, 3, 4] Multidetector CT urography (MDCTU) has improved the assessment of renal and urinary tract lesions with the use of reformatted images, such as multiplanar reconstruction and maximum intensity projection. [11] In a study of the literature from 1997 to 2017, Mthalane et al found that MDCT can reproduce images comparable to those of intravenous excretory urography for renal tuberculosis, along with being able to better assess the renal parenchyma and surrounding spaces. [12]

CT scanning is useful not only in the diagnosis of renal tuberculosis but also in the assessment of renal function and the severity of disease. It may also detect the involvement of other abdominal organs. [25] Plain radiography may provide a clue to the diagnosis and may guide further imaging. [26, 27] Because the type and distribution of calcification may be suggestive of tuberculosis, CT scans (with the ability to depict calcification) may be helpful. [28] MRI is useful when fistulae or tuberculous tracts are formed. [25, 29, 30, 31] Hysterosalpingographic images may suggest female genital tuberculosis by demonstrating abnormal findings within the uterus and fallopian tubes.

Ultrasonographic findings in the appropriate clinical setting may help to avoid orchiectomy for benign testicular disease. In patients with female genital tract tuberculosis, awareness of ultrasonographic changes associated with tuberculous infection may improve diagnostic accuracy and help the clinician to avoid clinical mismanagement and surgical explorations in patients with genital infections associated with wet-type tuberculosis (peritonitis). [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41]

Limitations of techniques

All imaging findings may be normal in patients with early genitourinary tuberculosis. Genitourinary calcification may occur in patients with diabetes mellitus and schistosomiasis. Brucellosis also may mimic tuberculosis. The differential diagnosis of an adnexal mass is wide. A congenital megacalyx and focal papillary necrosis may mimic renal tuberculosis radiologically. Papillary necrosis can result from tuberculosis. A tuberculous testicular granuloma may mimic a testicular neoplasm on ultrasonographic images.

Diagnosis of genitourinary tract tuberculosis is important to the radiologist, because the disease is treatable. The possibility of the diagnosis should always be kept in mind, because clinical and radiologic manifestations are varied and may be nonspecific.

Small areas of calcification are difficult to detect on MRI scans, although they are pivotal to the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Hysterosalpingographic findings are also nonspecific; blockage of the fallopian tubes is not pathognomonic for tuberculous salpingitis and may occur as a result of other forms of infective processes of the genital tract.

Findings in all imaging modalities used in the diagnosis of genitourinary tuberculosis are essentially nonspecific, because the diagnosis is based on the presence of calcification, cavities, and strictures, which are associated with a long list of differential diagnoses. However, a fairly confident diagnosis can be made in most instances with clinical correlation.

Radiography

Signs of active or inactive extrarenal tuberculosis (such as osseous or paraspinal changes of tuberculosis, as well as old, healed, calcified splenic, hepatic, lymph node, and adrenal granulomas) may be apparent. Chest radiographs may show evidence of active or healed tuberculosis in 50% of patients, with the remaining patients having normal chest studies. [6]

(See the radiographic images below.)

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a woman with renal tuberculosis shows calcification of varying patterns (curvilinear, amorphous, speckled).

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a woman with renal tuberculosis shows calcification of varying patterns (curvilinear, amorphous, speckled).

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows an irregular cavity at the upper pole calyx of the right kidney. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the liver, spleen, and right adrenal gland due to calcified tuberculous granuloma.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows an irregular cavity at the upper pole calyx of the right kidney. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the liver, spleen, and right adrenal gland due to calcified tuberculous granuloma.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows multiple curvilinear calcifications in the left kidney. Note the calyceal dilatation in the upper pole of the left kidney due to infundibular stricture.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows multiple curvilinear calcifications in the left kidney. Note the calyceal dilatation in the upper pole of the left kidney due to infundibular stricture.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a man with renal tuberculosis shows irregular cavitation of the left upper pole calyx. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the spleen.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a man with renal tuberculosis shows irregular cavitation of the left upper pole calyx. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the spleen.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Intravenous urography series in a man with renal tuberculosis shows marked irregularity of the bladder lumen due to mucosal edema and ulceration.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Intravenous urography series in a man with renal tuberculosis shows marked irregularity of the bladder lumen due to mucosal edema and ulceration.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a woman with a history of tuberculosis of the breast. The film shows irregular cavitation in the lower pole calyx of the left kidney due to renal tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a woman with a history of tuberculosis of the breast. The film shows irregular cavitation in the lower pole calyx of the left kidney due to renal tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with advanced renal tuberculosis shows lobar calcification with no excretion of contrast on intravenous urogram.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with advanced renal tuberculosis shows lobar calcification with no excretion of contrast on intravenous urogram.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lobar calcification in a large destroyed right kidney in a patient with renal tuberculosis. Note the involvement of the right ureter.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lobar calcification in a large destroyed right kidney in a patient with renal tuberculosis. Note the involvement of the right ureter.

Changes of renal tuberculosis are unilateral in 75% of patients. A tuberculoma usually starts as a localized, caseating lesion, most commonly in the upper pole of the kidney, although it may arise anywhere. With time, the nidus of infection enlarges and ruptures into a neighboring calyx, discharging necrotic, caseous material and distorting the calyx. At this stage, a variety of radiologic abnormalities may be demonstrated, including smudged papillae due to surface irregularity of the papillae, a moth-eaten calyx (early sign), irregular tract formation from the calyx to the papilla, and large, irregular cavities with extensive destruction secondary to papillary necrosis. Changes may be detected on intravenous urography, retrograde pyelography, and on some CT and MRI scans.

The kidney enlarges initially but subsequently may return to normal or become atrophic. Once communication with a tuberculous cavity is established, the involved calyx becomes an ulcerocavernous lesion. The finding of hydrocalyces with no pelvis dilatation or an atrophic pelvis is highly suspicious for tuberculosis. The cephalic retraction of the inferior medial margin of the renal pelvis at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ), or the "hiked up renal pelvis," is another suggestive urographic/pyelographic change.

The infection spreads to the stem of the involved calyx, which may develop a stricture, thus sealing off the involved calyx. This change may be apparent as a mass lesion. Dilated calyces often are associated with infundibular strictures and may be demonstrated radiologically. The lesions may be better depicted on cross-sectional imaging.

If the ulcer or stricture extends to the renal pelvis or to the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ), urine outflow obstruction may occur. In this instance, an intravenous urogram may show delayed function, clubbed calyces, or absence of function. At this stage, a "putty" kidney may be depicted. Ultrasonography, CT scanning, and MRI can better depict an outflow obstruction.

If tuberculous infection extends directly to the rest of the kidney, the entire kidney becomes a bag of caseous, necrotic pus. Plain radiographs may reveal dystrophic calcification, but intravenous urography usually shows absence of function, although a faint nephrogram may be demonstrated if some function remains. Associated renal calculi are found in as many as 20% of patients with renal tuberculosis.

The final outcome of renal tuberculosis is autonephrectomy, which represents a small, shrunken, scarred, nonfunctioning kidney and is often associated with dystrophic calcification. [1]

Renal calcification is present in as many as 50% of patients and may appear as an amorphous, granular opacification, which is associated with active, granulomatous infection, and dense, punctate calcification, which is associated with healed tuberculomas. Shell-like calcification within the renal collecting system and a thinned-out renal cortex are more a feature of autonephrectomy. Infection may extend into the psoas sheath and/or the perirenal or pararenal spaces.

Ureter findings

A radiograph of the ureters is shown in the image below.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with tuberculosis of the ureter and bladder. The lower end of the right ureter demonstrates an irregular caliber with an irregular stricture at the right vesico-ureteric junction. Note the asymmetric contraction of the urinary bladder, with marked irregularity due to edema and ulceration.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with tuberculosis of the ureter and bladder. The lower end of the right ureter demonstrates an irregular caliber with an irregular stricture at the right vesico-ureteric junction. Note the asymmetric contraction of the urinary bladder, with marked irregularity due to edema and ulceration.

Although ureteral involvement is usually unilateral, bilateral changes are asymmetric when they occur. The most common site of involvement is the lower third of the ureter. Mucosal granulomas may be demonstrated as intraluminal filling defects on intravenous urogram or retrograde pyelography.

Mucosal ulceration is difficult to depict radiologically but, in rare cases, may show as an irregularity in the contrast-filled ureter. The involved ureter may appear beaded or with a corkscrew configuration as a result of alternating dilatations and strictures. Ultimately, the ureter may form a rigid, aperistaltic, shortened tube.

Cladder findings

A radiograph of the bladder affected by tuberculosis is shown in the image below.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Intravenous urography series in a man with renal tuberculosis shows marked irregularity of the bladder lumen due to mucosal edema and ulceration.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Intravenous urography series in a man with renal tuberculosis shows marked irregularity of the bladder lumen due to mucosal edema and ulceration.

When tuberculosis involves the bladder, progressive thickening of the bladder wall occurs with increasing diminution of bladder volume. Trabeculation may develop. The vesicoureteric junction orifice may become fixed and patulous, resulting in vesico-ureteric reflux. The vesico-ureteric junction may be affected by progressive narrowing, causing stenosis and resulting in bilateral hydroureters and hydronephrosis. Bladder wall calcification is rare. Bladder tuberculosis may be complicated by fistulae or by sinus tract formation, although these complications are rare and are better demonstrated on CT and MRI scans.

Prostate findings

Tuberculous prostatic cavities or abscesses may discharge into the surrounding tissues, forming sinuses or fistulae to the perineum or rectum and eventually resulting in a watering-can perineum. These changes are demonstrated best on MRI scans.

Plain radiographs may show dense calcification within the prostatic bed, which can also be demonstrated on ultrasonographic and CT scans.

Urethrography or a micturating cystourethrogram typically demonstrates filling of variable, dilated prostatic ducts associated with destruction of the prostatic parenchyma.

Sloughing and irregular cavitation of the prostate eventually may result in a smooth-walled cavity that replaces the prostate.

Seminal vesicle findings

The image below is a radiograph of calcified seminal vesicles.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a patient with calcified seminal vesicles due to tuberculosis. Note the amorphous and speckled calcification in the right kidney.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a patient with calcified seminal vesicles due to tuberculosis. Note the amorphous and speckled calcification in the right kidney.

Calcification is depicted on plain abdominal radiographs in as many as 10% of patients with tuberculosis of the seminal vesicles. Calcification of the seminal vesicles is more common in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Epididymis and vas deferens findings

Calcification of the epididymis and vas deferens may be visualized on plain radiographs of the male pelvis and must be differentiated from diabetes and schistosomiasis.

Female genital tuberculosis findings

In the images below, tuberculosis of the uterus (top image) and of the fallopian tubes (second image) is displayed.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Hysterosalpingogram in a patient with tuberculosis of the uterus. The contour of the uterus is irregular, with nodular filling defects.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Hysterosalpingogram in a patient with tuberculosis of the uterus. The contour of the uterus is irregular, with nodular filling defects.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Hysterosalpingogram in a patient with tuberculosis of the fallopian tubes shows right-sided hydrosalpinx with an occluded left fallopian tube.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Hysterosalpingogram in a patient with tuberculosis of the fallopian tubes shows right-sided hydrosalpinx with an occluded left fallopian tube.

Tuberculosis can affect any part of the female genital tract but more commonly involves the fallopian tubes. Hydrosalpinx and pyosalpinx are usually large and may appear as soft-tissue masses on plain abdominal radiographs. The pyosalpinx may be calcified.

Tuberculous tubo-ovarian abscesses may calcify, are observed on either side of the pelvis, and sometimes appear as well-defined, homogeneous masses, occasionally with areas of increased density that presumably are due to the granuloma. Serpiginous or linear calcification can occur in the tubes.

Hysterosalpingographic findings may suggest a diagnosis. Hysterosalpingographic appearances vary as widely as do the pathologic changes observed in this condition. Tubal involvement is almost always bilateral, but the degree of involvement varies between the 2 sides. Hysterosalpingography (HSG) may demonstrate a flask-shaped dilatation of the fallopian tubes due to obstruction at the fimbria. Occasionally, the obstruction is at the uterine end of the tube; therefore, the tubes are not depicted.

HSG may demonstrate sacculation with infiltration of contrast material resembling salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Infiltration around the tube, which creates a cloudlike appearance of the delicate sinus tracts, has also been described. A characteristic hysterosalpingographic feature suggestive of tuberculosis has been described in which irregular contrast distribution resembling a cotton-wool plug occurs. Focal irregularity and areas of calcification may occur within the lumen of the fallopian tubes.

Obstruction of the fallopian tubes is not pathognomonic for tuberculosis and may occur with other pathology. In end-stage disease, the tubes become rigid, lack peristalsis, and resemble pipelike conduits. Within the endometrial cavity, tuberculous endometritis findings include adhesions, which may vary from very thin to very thick synechiae. In end-stage disease, the uterine cavity may be completely obliterated. Within the pelvis, calcified lymph nodes and ovaries may be observed.

Degree of confidence

Early features of renal tuberculosis may be difficult to detect, and the kidneys may appear entirely normal. With the development of a caseating cavity and calcification at the stage of autonephrectomy, a fairly reliable diagnosis can be achieved. Diagnosis of renal tuberculosis can be confirmed by examination of an early morning urine specimen using microscopy, but diagnosis depends on urine culture for tuberculosis. Certain features are highly suggestive of a tuberculous female genital tract, such as an irregular distribution of contrast on HSG, termed the cotton-wool plug appearance.

Renal calcification may occur in nephrocalcinosis, which has several causes (see the images below). Renal hydatid cysts, renal abscesses, and renal artery aneurysms may calcify and mimic renal tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lateral view of the abdomen in a patient with schistosomiasis shows tubular calcification of the ureters in contrast to the speckled calcification in tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lateral view of the abdomen in a patient with schistosomiasis shows tubular calcification of the ureters in contrast to the speckled calcification in tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Radiograph of the pelvis in a patient with schistosomiasis shows fine linear calcifications of the bladder wall with normal volume. In tuberculosis, the bladder is contracted and demonstrates speckled calcification.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Radiograph of the pelvis in a patient with schistosomiasis shows fine linear calcifications of the bladder wall with normal volume. In tuberculosis, the bladder is contracted and demonstrates speckled calcification.

Ureteric calcification more commonly occurs in patients with ]schistosomiasis, but differentiation from ureteric, tuberculous calcification is fairly reliable. In schistosomiasis, calcification is first observed in the bladder and then extends up the ureter. Ureteric calcification without bladder calcification is most unusual. In tuberculosis, calcification is more amorphous and patchy, and it extends down the ureter; moreover, the bladder is seldom calcified. Multiple strictures and nodules of ureteritis cystica are fairly rare in ureteric tuberculosis.

Calcification may occur within bladder tumors, or calcium may be encrusted on the surface of bladder tumors, which need to be differentiated from bladder tuberculosis. A shrunken bladder may be neurogenic, but the clinical presentation is not that of urinary tuberculosis.

Calcification of the epididymis and vas deferens may occur in patients with diabetes and schistosomiasis, as well as in patients with tuberculosis. Prostatic calcification may be the aftermath of chronic prostatitis, prostatic carcinoma, or diabetes mellitus.

Blockage of the fallopian tubes is not pathognomonic for tuberculous salpingitis and may occur as a result of previous ectopic pregnancy, iatrogenic or developmental causes, pelvic inflammatory disease, or other forms of infective processes of the genital tract.

Computed Tomography

Although intravenous urography is the primary modality for imaging renal tuberculosis, CT scans clearly reveal changes of renal tuberculosis, particularly in advanced disease. Changes such as calcification, calyceal dilatation without a hydropelvis, parenchymal loss, and extrarenal spread are well depicted. CT scans may demonstrate dense prostatic calcification in tuberculous prostatitis, sloughing, and irregular cavitation of the prostate, eventually resulting in a smooth-walled cavity that replaces the prostate. [23, 7, 8]

Multidetector CT urography (MDCTU) has improved the assessment of renal and urinary tract lesions with the use of reformatted images, such as multiplanar reconstruction and maximum intensity projection. [11] In a study of the literature from 1997 to 2017, Mthalane et al found that MDCT can reproduce images comparable to those of intravenous excretory urography for renal tuberculosis, along with being able to better assess the renal parenchyma and surrounding spaces. [12]

In a series of 42 patients with renal tuberculosis, Lu and associates described the following typical CT scan features, listed in order of decreasing frequency [42] :

-

One or more cysts surrounding a calyx, with thinning of overlying renal cortex

-

Thickened ureteric wall and calyx

-

Hydronephrosis

-

Renal calcification

According to the study, atypical features included the following:

-

Single or multiple low-density nodes in the renal parenchyma and (rarely) abdominal lymph node calcification

-

Calcification and low-density nodes in spleen and liver

-

Vertebral destruction

-

Paravertebral abscess

In just over 70% of patients with renal tuberculosis, contrast-enhanced CT scanning showed intensified HU (by 20 to approximately 120 HU) in the affected kidney.

Wang and associates reviewed the intravenous urograms and CT scans of 53 patients with urinary tuberculosis, [43] and the most common findings on intravenous urography were hydrocalycosis, hydronephrosis, or hydroureter subsequent to strictures. Renal parenchymal scarring was the most common finding on CT scans. The findings of renal parenchymal masses and scarring, thick urinary tract walls, and extraurinary tubercular manifestations were better depicted and were significantly more common on CT scans than they were on intravenous urograms.

Degree of confidence

Because the type and distribution of calcification features may be suggestive of tuberculosis, CT scans (with the ability to depict calcification) may show relatively specific findings. Although CT scans clearly demonstrate changes of advanced disease, sensitivity in early disease may be low, because scans do not demonstrate the detailed calyceal anatomy. Early disease may be missed on CT scans. Mimics of renal tuberculosis include schistosomiasis, diabetes mellitus, fungal infections, brucellosis, and focal papillary necrosis from other causes.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is good at depicting tuberculous cavities, sinuses tracts, fistulous communications, and extrarenal and extraprostatic spread. Multiplanar MRI allows evaluation of the disease extent in the prostatic bed and the presence of sinuses and fistulae. MRI contrast agents facilitate evaluation. MRI is also useful in the evaluation of peritonitis and adnexal masses. [8]

Renal parenchymal changes not dissimilar to acute pyelonephritis occur in renal involvement with tuberculosis. Active inflammation may cause focal tissue edema and vasoconstriction resulting in focal hypoperfusion well depicted on contrast-enhanced CT or MRI scans. Renal tuberculosis may manifest as single or multiple parenchymal nodules without other urinary tract involvement.

Variably-sized, well-defined parenchymal nodules are seen on ultrasonographic, CT, or MRI scans in cases of the so-called pseudotumoral type, . The pseudotumor may be difficult to differentiate from renal neoplasms, leading to unnecessary surgery. Renal pelvic and ureteric involvement presents as wall thickening and contrast enhancement of the affected segments on CT and MRI scans. Tuberculous involvement of the urinary bladder is depicted by bladder distortion associated with a ragged intraluminal wall; further damage results in a shrunken, small capacity urinary bladder. These changes are reflected on CT or MRI scans, appearing as wall thickening and shrinkage.

MRI features of a case of renal macronodular tuberculoma in an asymptomatic patient have been described. The lesion was hypointense on T1-weighted images, while a thick, irregular, hypointense peripheral wall and an intralesional fluid debris level were demonstrated on T2-weighted images. MRI contrast agents were not administered. [44]

MRI scans of tuberculous epididymitis show enlargement of the epididymis, with relatively low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, thereby indicating chronic inflammation or fibrosis. Features that demonstrate tuberculous involvement of the seminal vesicles and the vas deferens include wall thickening, contraction, and intraluminal or wall calcifications, which may be depicted on ultrasonograms or on CT or MRI scans.

Tuberculosis of the prostate takes the form of diffuse inflammation (prostatitis) or prostatic abscess. With a prostatic abscess, T2-weighted MRI shows a peripheral enhancing cystic mass with radiating, streaky areas of low signal intensity (so-called "watermelon skin"). Diffuse, dystrophic calcifications can be seen with chronic prostatic tuberculosis.

Tuberculous salpingitis often affects both fallopian tubes and reveals multifocal strictures and calcifications. A tubo-ovarian tuberculous abscess may extend through the peritoneum into the extraperitoneal compartment. Endometrial involvement occurs in 50% of patients with tubal tuberculosis. Tuberculous endometritis may cause severe uterine adhesions and mimic Asherman disease. These features are reflected in changes depicted on cross-sectional imaging.

Adrenal tuberculosis is the most common cause of adrenal insufficiency. Adrenal tuberculosis may be unilateral or bilateral; it may be seen as adrenal gland enlargement with central necrosis and calcifications. These changes are reflected on cross-sectional imaging, including MRI. These imaging features should be interpreted in the prevailing clinical context, because the radiologic differential diagnosis includes metastases, lymphoma, primary neoplasm, and hemorrhage.

Degree of confidence

MRI is an excellent modality for depicting extra-organ spread, as well as for demonstrating discharging sinuses and fistulae, but calcification is not readily seen. Sensitivity of MRI in the diagnosis of early genitourinary tract tuberculosis is low, and changes resulting from more advanced disease, as demonstrated on MRI scans, are nonspecific.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is not as sensitive as intravenous urography or CT scanning because of problems with identifying calyceal, pelvic, or ureteric abnormalities.

(Genitourinary tuberculosis is displayed in the ultrasound images below.)

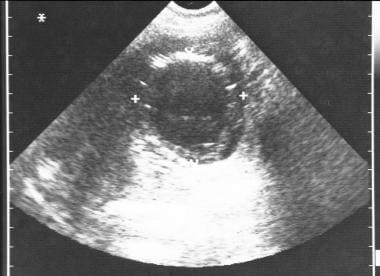

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the pelvis shows left tubo-ovarian abscess resulting from tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the pelvis shows left tubo-ovarian abscess resulting from tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the scrotum in a young male patient shows left epididymo-orchitis resulting from tuberculosis.

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the scrotum in a young male patient shows left epididymo-orchitis resulting from tuberculosis.

The kidney may appear entirely normal in early or later stages of renal tuberculosis; later, hypoechoic/cystic masses communicating with the collecting system may be observed, representing "excluded" calyces, without dilatation of the renal pelvis. Large abscesses may distort the renal contour and may mimic tumors or cysts.

Usually, renal tuberculomas appear as a solid mass with diminished through transmission; however, a diffuse, infiltrative type of renal tuberculosis has been described in which the kidney may appear normal on ultrasonographic images. Fibrosis and scarring may appear identical to chronic pyelonephritis or multiple renal infarcts.

Calcification is common in the late stages and varies from punctate foci to dense calcification of the entire kidney, which is associated with hydronephrosis or atrophy.

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy delivered intravesically in the treatment of superficial bladder cancer may be complicated by a renal granuloma, probably as a result of vesicoureteric reflux. The granulomas have been reported as small, hypoechoic intrarenal masses. Bladder tuberculosis causes fibrosis and mucosal thickening, leading to a thick-walled, small-volumed bladder with vesicoureteric reflux.

Tuberculosis is an unusual cause of chronic epididymitis and epididymo-orchitis. [45] In tuberculous epididymitis, the epididymis may appear heterogeneous and hypoechoic, associated with concomitant hypoechoic lesions in the testes and a discharging sinus. The most notable finding is an enlarged and heterogeneous epididymis, predominantly in the body and tail. [46]

Testicular involvement is shown as a diffusely hypoechoic testis or focal intratesticular areas. Thickening of the scrotal wall and tunica albuginea, as well as moderate hydrocele, may occasionally be observed. Follow-up scans may reveal intratesticular abscesses. The testes may become as hard as stone, which is associated with extratesticular calcification.

In one series of 15 patients with genital tuberculosis and peritonitis, 12 patients had wet peritonitis and 3 had dry (adhesive) peritonitis. An adnexal mass was present in 93% of the patients, peritoneal thickening in 69%, omental thickening in 61%, and endometrial involvement in 83%. Associated ascites may be septated, particulated, and/or loculated.

Degree of confidence

Ultrasonographic findings may suggest genitourinary tuberculosis in the appropriate clinical setting, and in the case of benign disease, findings may help clinicians avoid the use of renal surgery or orchiectomy. In female patients with genital tract tuberculosis, awareness of ultrasonographic changes associated with the infection may improve diagnostic accuracy and allow clinical mismanagement and surgical explorations in genital infections associated with wet-type (peritonitis) tuberculosis to be avoided. Clinically, tuberculosis infection of the scrotum often cannot be distinguished from lesions such as tumor and infarction. [47] High-resolution ultrasonography is currently the best technique for imaging the scrotum and its contents.

Mimics of renal tuberculosis include such conditions as focal compensatory hypertrophy, focal nontuberculosis hydronephrosis, acute focal bacterial nephritis, focal or global xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, BCG granulomas, and chronic pyelonephritis. Tuberculous autonephrectomy may resemble renal hydatid disease. Bladder tuberculosis may mimic bladder papilloma/transitional cell tumors. Tuberculous epididymitis may mimic other forms of chronic epididymitis/orchitis, testicular granulomas, and tumors.

Nuclear Imaging

The role of radionuclides in imaging patients with renal tuberculosis is confined to assessment of relative renal function by renography when surgery or nephrectomy is contemplated. The agents used are technetium-99m (99mTc) diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (DTPA), 99mTc mercaptotriglycylglycine (MAG-3), and iodine-123 (123I) orthoiodohippurate (OIH). Isotope renography is the most sensitive imaging modality available for the assessment of renal function. Radionuclide imaging usually cannot differentiate between the various causes of depressed renal function.

Diagnosis is often delayed because symptoms are typically nonspecific or absent, and there have been reports of miliary tuberculosis, such as abdominal tuberculosis, being misdiagnosed as other diseases. DiRenzo reports on 2 such cases in which an incorrect dose of malignancy was made in patients who underwent FDG-PET imaging. [18]

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a woman with renal tuberculosis shows calcification of varying patterns (curvilinear, amorphous, speckled).

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows an irregular cavity at the upper pole calyx of the right kidney. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the liver, spleen, and right adrenal gland due to calcified tuberculous granuloma.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with renal tuberculosis shows multiple curvilinear calcifications in the left kidney. Note the calyceal dilatation in the upper pole of the left kidney due to infundibular stricture.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a man with renal tuberculosis shows irregular cavitation of the left upper pole calyx. Note the multiple tiny calcifications in the spleen.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Intravenous urography series in a man with renal tuberculosis shows marked irregularity of the bladder lumen due to mucosal edema and ulceration.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a woman with a history of tuberculosis of the breast. The film shows irregular cavitation in the lower pole calyx of the left kidney due to renal tuberculosis.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with advanced renal tuberculosis shows lobar calcification with no excretion of contrast on intravenous urogram.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lobar calcification in a large destroyed right kidney in a patient with renal tuberculosis. Note the involvement of the right ureter.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Excretory urography in a patient with tuberculosis of the ureter and bladder. The lower end of the right ureter demonstrates an irregular caliber with an irregular stricture at the right vesico-ureteric junction. Note the asymmetric contraction of the urinary bladder, with marked irregularity due to edema and ulceration.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a patient with calcified seminal vesicles due to tuberculosis. Note the amorphous and speckled calcification in the right kidney.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Lateral view of the abdomen in a patient with schistosomiasis shows tubular calcification of the ureters in contrast to the speckled calcification in tuberculosis.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Radiograph of the pelvis in a patient with schistosomiasis shows fine linear calcifications of the bladder wall with normal volume. In tuberculosis, the bladder is contracted and demonstrates speckled calcification.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Hysterosalpingogram in a patient with tuberculosis of the uterus. The contour of the uterus is irregular, with nodular filling defects.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Hysterosalpingogram in a patient with tuberculosis of the fallopian tubes shows right-sided hydrosalpinx with an occluded left fallopian tube.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the pelvis shows left tubo-ovarian abscess resulting from tuberculosis.

-

Genitourinary tract tuberculosis. Ultrasonographic image of the scrotum in a young male patient shows left epididymo-orchitis resulting from tuberculosis.