Practice Essentials

A tracheobronchial tear or laceration or injury is an uncommon injury to the tracheobronchial tree, usually involving the trachea or both right and left mainstem bronchi, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Tracheobronchial tears are usually related to blunt trauma involving partial or complete laceration or puncture of the tracheal or bronchial wall. Most patients have associated rib fractures, which may be the cause of the laceration. Tracheal membrane laceration most often occurs in the midline and the lower third of the trachea, which can complicate endotracheal intubation, dilatational tracheostomy, or rigid bronchoscopy. [1, 2, 3, 4, 32]

Almost 80% of tracheobronchial injuries in blunt trauma are expected to cause death at the site or during transport to the hospital, given multiple severe associated injuries. However, outcomes appear to be improving with better prehospital management. A high index of suspicion, early diagnosis, and management of tracheobronchial injuries are essential for a favorable outcome. [5] Patients may present with nonspecific signs and symptoms, requiring a high index of suspicion along with accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment. [6]

Imaging modalities

Clinical findings of tracheobronchial injuries (TBIs) include subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and pneumothorax. Chest computed tomography (CT) and bronchoscopy are important examinations to evaluate the injured site and the patient’s condition. [7] The gold standard for detection of tracheal tear/injury is fiberoptic bronchoscopy, which can also facilitate initial safe management of the airway in cases of suspected or proven TBIs. [5]

Chest radiography is the standard initial imaging modality for evaluation of most chest conditions, including possible TBI, but CT is preferred when a tracheobronchial tear is suspected. [8, 9] In appropriate circumstances, multiplanar or virtual endoscopic reconstructions from CT scan data can be done to clarify questionable findings. [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide findings similar to those seen on CT scanning, but patient preparation is more difficult and MRI services may not be available. Angiography is not a primary procedure for evaluating patients who have tracheobronchial trauma but is often done to assess associated thoracic trauma. Active bleeding at the tracheobronchial tear can be visible on aortography or on pulmonary angiography.

Definitive diagnosis of a tracheobronchial tear is made by bronchoscopy or by surgical exploration. If clinical or radiographic findings suggest airway injury, diagnostic bronchoscopy is recommended. [1, 17]

(The animation below simulates images from a bronchoscopy.)

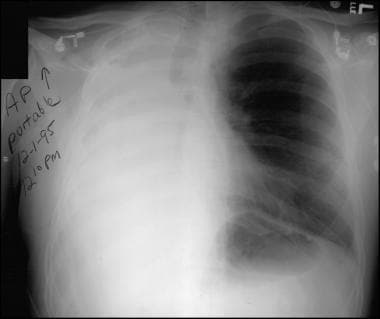

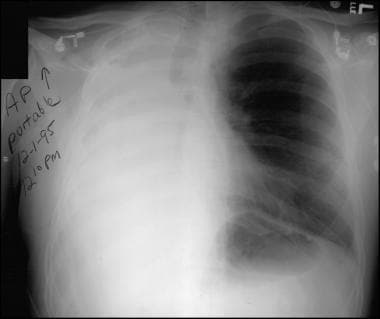

The radiograph below reveals injury to the right mainstem bronchus.

Frontal chest radiograph from a 26-year-old man after major trauma. This image shows complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms, abrupt termination of the right mainstem bronchus, and multiple upper right rib fractures.

Frontal chest radiograph from a 26-year-old man after major trauma. This image shows complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms, abrupt termination of the right mainstem bronchus, and multiple upper right rib fractures.

Other images below display tracheobronchial tears.

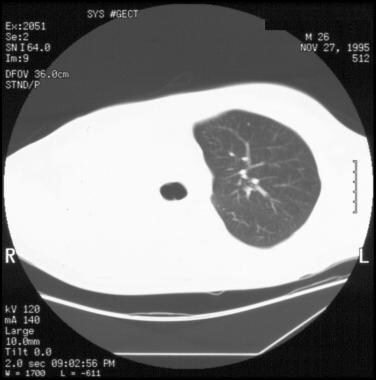

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus and complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms.

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus and complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms.

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows multiple right rib fractures and a moderate-sized pleural effusion. There is mediastinal shift toward the side of injury. Fluid density is present in the right main bronchus, probably representing hemorrhage.

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows multiple right rib fractures and a moderate-sized pleural effusion. There is mediastinal shift toward the side of injury. Fluid density is present in the right main bronchus, probably representing hemorrhage.

Angiography is not a primary procedure for evaluating patients who have tracheobronchial trauma; however, angiography is often used to assess any associated thoracic trauma. If active bleeding is present at the tracheobronchial tear, it can be visible on aortography or pulmonary angiography.

Treatment

Conservative management is encouraged for a spontaneously breathing or stable patient on noninvasive ventilation. Surgical repair is mandatory when mechanical ventilation is required or when bridging of the injury is impossible. [18]

Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation can be safely used to treat patients with a range of TBIs with low rates of postoperative morbidity. Acceptable postoperative outcomes can be achieved for this cohort of clinically complex patients when treatment is provided via a multidisciplinary team approach at high-volume specialist centers. [19]

Marano et al reported that a robotic approach can facilitate repair of this injury while reducing both the potential risk of conversion to open surgery and the associated increased risk of postoperative respiratory complications. [20]

Radiography

Radiographic findings of tracheobronchial tears (see the image below) reflect the location and extent of the injury or injuries. Due to nonspecific symptoms and indirect radiologic signs, diagnosis is often delayed. [6] The most specific signs of tracheobronchial tears include an appropriately placed endotracheal tube that clearly extends beyond the expected tracheal lumen and the classic fallen-lung sign. [21, 22] Other signs are less conclusive and usually require bronchoscopic confirmation. Tracheobronchial tears may not be visible if the tracheal mucosa remains intact or is sealed by fibrin.

Frontal chest radiograph from a 26-year-old man after major trauma. This image shows complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms, abrupt termination of the right mainstem bronchus, and multiple upper right rib fractures.

Frontal chest radiograph from a 26-year-old man after major trauma. This image shows complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms, abrupt termination of the right mainstem bronchus, and multiple upper right rib fractures.

In 10% of affected patients, the tear is incomplete, with preservation of the peritracheal or peribronchial connective tissue sheath or sealing of the tear by fibrin. For these patients, the injury is not apparent on radiographs. Among the most severely injured patients, the airway separates completely at the site of the injury with a visibly obvious distortion of the tracheobronchial anatomy. A pneumomediastinum, a pneumothorax, or both are usually present when these extensive injuries occur.

The location of the tear is important in determining whether a pneumomediastinum or a pneumothorax develops. The most common site of tear is near the carina because the airway is fixed and is subject to shear injury. Tears within the mediastinal pleura cause a pneumomediastinum; tears beyond the mediastinal pleura cause a pneumothorax. Because the left main bronchus has a longer mediastinal course than the right main bronchus, injury to the left main bronchus is more likely to cause a pneumomediastinum, whereas injury to the right main bronchus is more likely to cause a pneumothorax. Note that in severe injuries, both a pneumomediastinum and a pneumothorax may be present.

A pathognomonic indication of tracheobronchial tears—the fallen-lung sign—is visible in some patients with severe injury. [21] In cases of uncomplicated pneumothorax, the bronchus remains fixed at the hilum and the peripheral lung retracts from the parietal pleura toward the hilum. With complete laceration of the main bronchus, the bronchus may become partially or completely detached, allowing the lung to fall into a dependent lateral position and producing the fallen-lung sign.

Other important radiographic findings that are associated with tracheobronchial tears include incorrect location or overdistention of the endotracheal tube (ETT) cuff and a persistent pneumothorax that is unrelieved by appropriate placement of a thoracostomy tube. [21, 22] A bayonet deformity or bronchial discontinuity may be present, and if the tear causes obstruction, peripheral consolidation or atelectasis without air bronchograms may be seen.

In the typical traumatic transection of the cervical trachea, the infrahyoid muscle ruptures and the suprahyoid muscle retracts, raising the hyoid bone. Abnormal hyoid bone elevation suggests a cervical tracheal tear.

Computed Tomography

CT scanning is the imaging method of choice for evaluating a possible tracheobronchial tear because this modality clarifies and confirms the radiographic signs of tracheobronchial tears and occasionally adds unique information (see the images below). Additionally, because tracheobronchial injury occurs in circumstances of severe trauma, CT scanning allows evaluation of secondary injuries to critical structures such as the aorta or the great vessels. [2, 23]

In some instances, definitive evidence of a tracheobronchial tear is depicted on CT scans. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, reformatted images along the luminal axis of the airway or virtual endoscopy may prove helpful. The high-quality images that can be obtained with multidetector CT scanners allow excellent virtual endoscopic reconstructions. [2, 23] In other instances, findings are inconclusive and should be interpreted in the proper clinical context. CT scanning can be falsely negative, particularly in relatively minor injuries, and bronchoscopy should be performed in patients with a strong clinical suggestion of a tracheobronchial tear.

With the patient in the supine position, the affected lung falls posterolaterally away from the hilum in the CT scan variation of the fallen-lung sign. A small pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum is more easily visible on CT scans than on radiographs. These features are seen in the images below. [24]

Subtle airway discontinuity or irregularity and small focal peritracheal or peribronchial gas collections are observed much better on CT scans. Active bleeding from the lacerated airway can occasionally be identified on enhanced CT scan images.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan image with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image and the 4 CT scans immediately below again demonstrate abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan image with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image and the 4 CT scans immediately below again demonstrate abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan images with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan images with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows findings similar to those seen on CT scanning. The primary strengths of MRI include a multiplanar display and high tissue contrast. However, these strengths are offset by the relative difficulty involved in preparing the patient for MRI, the fact that monitoring trauma patients is more difficult during the imaging examination, and the limited availability of MRI.

As with CT scanning, the more common findings of tracheobronchial tears on MRI are variable, nonspecific, and only suggestive. MRI occasionally may be useful in depicting the location and extent of injury in this condition.

As with conventional radiography and CT scanning, MRI can be falsely negative, particularly in relatively minor injuries and in patients with a strong clinical suggestion of a tracheobronchial tear.

Nuclear Imaging

Patients with tracheobronchial tears have diverse presentations on ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scans, depending on the severity of the injury. [25] In minor injuries in which there is intact blood flow and no airway obstruction or pneumothorax, a tracheobronchial tear is not detectable. If tracheobronchial trauma causes partial or complete airway obstruction with no associated vascular injury, normal physiologic response diminishes perfusion to the region of impaired ventilation, yielding a V/Q mismatch. In the most severe injuries, in which airflow and perfusion are disrupted, a matched defect is visible.

Although these physiologic responses are identifiable on V/Q imaging, CT scanning and bronchoscopy are more specific in the diagnosis of tracheobronchial tears. The degree of confidence is low with nuclear imaging. As with other imaging studies, false-negative examinations can occur when minor injuries are present.

-

Animated cine images from virtual bronchoscopy. The animation begins with a view of the carina and advances distally into the right main bronchus. An obstruction of the right main bronchus is consistent with a bronchial tear.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Cine image from virtual bronchoscopy.

-

Frontal chest radiograph from a 26-year-old man after major trauma. This image shows complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms, abrupt termination of the right mainstem bronchus, and multiple upper right rib fractures.

-

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus and complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms.

-

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus and complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms.

-

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus and complete opacification of the right hemithorax without air bronchograms.

-

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows multiple right rib fractures and a moderate-sized pleural effusion. There is mediastinal shift toward the side of injury. Fluid density is present in the right main bronchus, probably representing hemorrhage.

-

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows multiple right rib fractures and a moderate-sized pleural effusion. There is mediastinal shift toward the side of injury. Fluid density is present in the right main bronchus, probably representing hemorrhage.

-

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows multiple right rib fractures and a moderate-sized pleural effusion. There is mediastinal shift toward the side of injury. Fluid density is present in the right main bronchus, probably representing hemorrhage.

-

10-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows multiple right rib fractures and a moderate-sized pleural effusion. There is mediastinal shift toward the side of injury. Fluid density is present in the right main bronchus, probably representing hemorrhage.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan image with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image and the 4 CT scans immediately below again demonstrate abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan images with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the lung window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image demonstrates abrupt termination of the right main bronchus, complete opacification of the right hemithorax with few air bronchograms, subcutaneous emphysema, a moderate-sized anterior pneumothorax, and a pneumomediastinum. Note that the azygos vein is outlined by mediastinal gas. The superior segment of the left lower lobe is atelectatic.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows loculated right pleural effusion, longitudinal sternal fracture, and right rib fractures.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows loculated right pleural effusion, longitudinal sternal fracture, and right rib fractures.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows loculated right pleural effusion, longitudinal sternal fracture, and right rib fractures.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows loculated right pleural effusion, longitudinal sternal fracture, and right rib fractures.

-

5-mm axial computed tomography (CT) scan with the mediastinal window settings beginning at the level of the carina. This image shows loculated right pleural effusion, longitudinal sternal fracture, and right rib fractures.