Practice Essentials

Thymic epithelial tumors (TETs), according to the 3-compartment model, originate in the prevascular compartment, which is immediately posterior to the sternum and anterior to the pericardium and great vessels. The thymic gland comprises 2 types of cells: (1) epithelial cells, which can develop into thymoma and thymic carcinoma, and (2) lymphoid cells, which can develop into lymphoma. Thymic epithelial neoplasms, thymoma, thymic carcinoma, and thymic neuroendocrine tumors, although rare, are still the most common primary neoplasms of this compartment. These tumors typically present in the fifth and sixt decades of life with no gender prediliction. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Although thymic tumors are centered in the prevascular compartment, cases have been reported in the neck and other compartments. Tumors of thymic, lymphatic, or germ cell origin most commonly occur in this compartment, although aberrant parathyroid or thyroid tissue masses are sometimes found, along with vascular and mesenchymal tissue masses. These can present with venous obstruction, dysphagia, or stridor. Many conditions are associated with thymomas, with myasthenia gravis being the most common (between 30 and 50% of patients with thymoma have myasthenia gravis). Other conditions include pure red cell aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and nonthymic malignancies. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

The most widely used classification system for thymic epithelial tumors is the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, which is based on the morphology of the epithelial cells and the ratio of the lymphocytes to epithelial cells. The WHO classification correlates well with the likelihood of invasiveness. The Masaoka-Koga classification describes the extent and spread of thymic epithelial malignancies, which is assessed at surgery. TNM staging systems for TETs are critically important for guiding treatment strategies. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Imaging modalities

Conventional radiology is the first imaging technique to perform when a prevascular compartment mass is suspected. A large anterior mediastinal mass is readily identified by chest radiography, as it typically appears as an extra soft tissue mass or opacity. Although the density of a soft tissue mass is similar to mediastinal structures, the silhouette sign, in which there is a loss of normal anatomic borders, helps make the diagnosis. Identifying a small mediastinal mass is more difficult. The presence of an anterior junction line, which represents the point of contact between the anterior lungs and their pleural surfaces anterior to the cardiovascular structures, can help exclude the presence of an anterior mediastinal mass; however, this line is seen in only 20% of normal chest radiographs. A lateral view is warranted and performed in most of cases at first presentation. Calcification, either morphous or flocculent, can sometimes be demonstrated.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is routine and is very valuable in the diagnosis of thymic lesions that are usually of soft tissue attenuation and are mostly located between the sternum and the great vessels. A cystic component and calcification (10-50%) can be seen with these tumors. Calcification is more common in malignant thymic tumors but is not discriminatory as an isolated finding. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used. Routine chest CT and MRI can effectively identify thymoma, but neither is reliable to differentiate between thymic hyperplasia and normal thymus in patients with myasthenia gravis. Standard imaging for thymic tumors is IV contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax, which provides a complete exploration of the mediastinum and pleura from the apex to the costodiaphragmatic recesses. The CT images also help differentiate between the masses encroaching on the mediastinum from lung and other structures and the masses originating in the mediastinum. [8, 9, 1, 2, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

The eighth edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors includes an official staging system for thymic epithelial tumors recognized by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). Thymic epithelial tumors with clearly invasive or metastatic features seen on CT are associated with having higher AJCC/UICC pathologic TNM stage. However, features of lobulated contour and heterogeneous internal density are also associated with higher-stage disease. [9, 11]

Ultrasonography has been used to differentiate between solid and cystic masses in the medistinum and to determine whether adjacent structures are affected. It may also be useful in assessing cardiac abnormalities due to mediastinal tumor.

(See the images below.)

About one half of all thymic tumors are malignant in individuals aged 20-40 years, and one third are malignant in persons younger than 20 years and those older than 40 years. (A malignant thymic tumor is seen in the image below.)

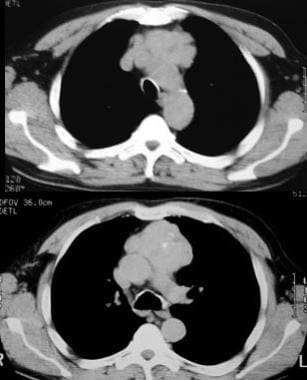

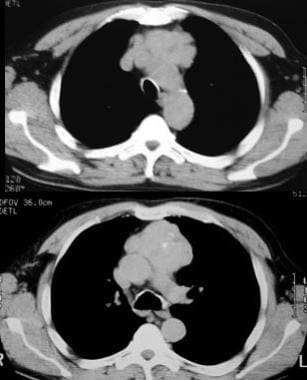

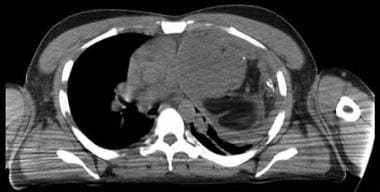

Malignant thymoma. Chest CT scan in a 61-year-old man with myasthenia gravis demonstrates a large, lobulated mass with punctate calcification in the anterior mediastinum; these findings are consistent with a thymoma.

Malignant thymoma. Chest CT scan in a 61-year-old man with myasthenia gravis demonstrates a large, lobulated mass with punctate calcification in the anterior mediastinum; these findings are consistent with a thymoma.

Radiography

Many thymomas may be visualized using routine chest radiographs in posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views. A thymoma frequently appears as a smooth, lobulated mass in the superior aspect of the prevascular compartment of the mediastinum, often projecting into one of the hemothoraces. The mass may be calcified or cystic.

In most cases, thymolipomas are detected incidentally on chest radiographs. They are often large, ranging up to 36 cm in diameter (mean, 18 cm) at the time of diagnosis. Thymolipomas may project into the hemithoraces; they may be seen draping over the heart and extending as far as the costophrenic angles. They can be easily mistaken for pleural or pericardial tumors or even pulmonary sequestration.

(See the images below.)

Computed Tomography

From birth to puberty, CT scan attenuation of the thymus is comparable to that of the chest wall musculature. The outer contours of the thymus may be convex laterally. The lobes, though separate, may have a triangular shape and may be slightly rotated to the left. The junction between the lobes is about 2 cm to the left of the midline.

From puberty to 30 years of age, the overall attenuation value diminishes secondary to fatty infiltration; during this period, attenuation is less than that of skeletal muscle. The thymus is often seen as a discrete triangular or bilobed structure, with the outer borders appearing straight or slightly concave laterally.

After the age of 30 years, remnants of thymic tissue appear as small islands of soft tissue attenuation; these islands appear as linear, oval, or small and round configurations on a background of more abundant fat.

In the older patient, only a thin fibrous skeleton of the thymus remains. At this point, the thymus is almost totally composed of fat.

The most reliable and meaningful measurements of the thymus are related to its thickness. Before the age of 20 years, 1.8 cm is the normal thickness; thereafter, the normal thymus does not exceed 1 cm in thickness.

(Changes in the thymus over time are demonstrated in the image below.)

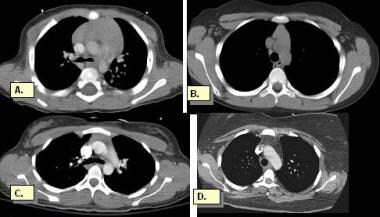

Normal thymus. The thymus is located anterior to the aortic arch, and sometimes 2 lobes can be seen. The thymus is prominent in newborns, occupying most of the anterior mediastinum. After puberty, fat progressively infiltrates the thymic tissue. At age 40 years, the thymus is nearly completely replaced with fat, and only slight residual nodular density of thymic tissue remains. A, Normally prominent thymus at age 7 months. B, Thymus in a 9-year-boy. C, Increasing fatty infiltration of the thymus noted in a 20-year-old man. D, The thymus has involuted and is atrophic in a 38-year-old man. Only a few nodular attenuations are visible.

Normal thymus. The thymus is located anterior to the aortic arch, and sometimes 2 lobes can be seen. The thymus is prominent in newborns, occupying most of the anterior mediastinum. After puberty, fat progressively infiltrates the thymic tissue. At age 40 years, the thymus is nearly completely replaced with fat, and only slight residual nodular density of thymic tissue remains. A, Normally prominent thymus at age 7 months. B, Thymus in a 9-year-boy. C, Increasing fatty infiltration of the thymus noted in a 20-year-old man. D, The thymus has involuted and is atrophic in a 38-year-old man. Only a few nodular attenuations are visible.

Thymic hyperplasia

CT scanning may show symmetrical, diffuse enlargement of the thymus. When the enlargement is asymmetrical, it may mimic a thymoma; thymoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. [16]

About two thirds of patients with myasthenia gravis have thymic hyperplasia; 25-50% of these patients are likely to have a normal thymus on CT scanning. Histologic analysis of the thymic medulla reveals numerous lymphoid follicles with active germinal centers.

Mature teratoma

On CT, teratomas are sharply defined; low-attenuation cystic components predominate. Fatty tissue is seen in about 50% of cases, and fat-fluid levels have been reported. Foci of calcification and ossification are commonly seen; in addition, soft tissue attenuation may be depicted. In rare cases, the tumor may erode and rupture into adjacent structures, such as the lung, tracheobronchial tree, and pleural space. (See the image below.)

Seminoma

On CT scans, seminomas are usually large and homogeneous, with soft tissue attenuation. Areas of low attenuation often are present secondary to necrosis and hemorrhage.

Nonseminomatous tumor

Nonseminomatous tumors include embryonal carcinoma, endodermal sinus tumor, choriocarcinoma, and mixed germ cell tumor. On CT scans, these lesions are often large and heterogeneous, with large (>50%) areas of low attenuation. They may contain areas of calcification.

Thymic lymphoma

On CT scans, the thymus is enlarged, symmetrically or asymmetrically; this enlargement often makes it difficult to differentiate the thymus from the enlarged surrounding lymph nodes. At times, differentiating the lymphoma from a thymoma is difficult, although the clinical picture and the presence of other sites of lymphadenopathy are often helpful in the diagnosis.

(See the image below.)

Thymolymphoma. Contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrates a large, lobulated, soft tissue mass in the anterior mediastinum that posteriorly displaces the aorta and pulmonary artery.

Thymolymphoma. Contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrates a large, lobulated, soft tissue mass in the anterior mediastinum that posteriorly displaces the aorta and pulmonary artery.

Thymoma

CT scanning is highly sensitive for thymomas. If the thymus appears grossly asymmetrical or if it has a lobular configuration, the diagnosis of a thymoma should be strongly considered. However, thymomas cannot be distinguished from other thymic masses on CT scans unless fat is visible. Thymomas are usually homogeneous and show mild enhancement with the use of contrast. They tend to grow to one side of the mediastinum or the other. Cystic degeneration, necrosis, and old hemorrhage present as areas of low attenuation. In cases of encapsulated thymoma, CT often demonstrates a preserved fat plane completely surrounding the mass. Inflammation and fibrous adhesions can mimic invasion. Invasive thymoma can show encasement of mediastinal structures. Pleural or pericardial implants can be seen, and in advanced cases, transdiaphragmatic spread may be visible. (Images of thymomas are shown below.) [17]

Malignant thymoma. Chest CT scan in a 61-year-old man with myasthenia gravis demonstrates a large, lobulated mass with punctate calcification in the anterior mediastinum; these findings are consistent with a thymoma.

Malignant thymoma. Chest CT scan in a 61-year-old man with myasthenia gravis demonstrates a large, lobulated mass with punctate calcification in the anterior mediastinum; these findings are consistent with a thymoma.

Invasive thymoma. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a thymic mass with variable attenuations invading the adjacent mediastinum. Bilateral pleural effusions are also present, indicating pleural invasion.

Invasive thymoma. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a thymic mass with variable attenuations invading the adjacent mediastinum. Bilateral pleural effusions are also present, indicating pleural invasion.

Thymic carcinoma

Thymic carcinoma belongs to a group of uncommon epithelial neoplasms, and these account for 17-22% of thymic epithelial neoplasms. The vast majority are squamous cell carcinomas and are characterized by cytologic atypia and anaplasia. On CT scans, they often show central necrosis in a large tumor mass, with invasion and infiltration of adjacent structures, including the pericardium and/or lungs (40%). Pleural invasion is seen in 30% of cases, and 20% show vascular invasion into the superior vena cava or brachiocephalic vein. Because of their aggressive nature, thymic carcinomas are likely to produce hematogenous and lymphatic spread. Between 19 and 50% of patients present with distant metastases, most often to the bone, liver, lung, and adrenal gland at the time of diagnosis. Pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, or enlarged lymph nodes are also more likely with thymic carcinoma than with thymoma. [18]

Preoperative CT imaging features may help identify patients at risk for incomplete surgical resection of thymic carcinoma. A retrospecitive review of preoperative CT findings of 41 patients with thymic carcinoma found that in addition to lesion size, the feature associated with incomplete surgical resection was the degree of tumor contact with adjacent mediastinal vessels on the preoperative CT image (P=0.038). [19]

Thymolipoma

CT scanning reveals a fatty mass interspersed with varying amounts of thymic soft tissue. The whole mass often consists of adipose tissue except for a thin rim of thymic tissue; this finding is consistent with soft tissue attenuation and mimics a pure lipoma of the mediastinum.

(See the image below.)

Thymolipoma. CT scan of the chest shows a large anterior mediastinal mass displacing the mediastinal vascular structures to the right and projecting into the left thorax. The tumor is composed of soft tissue and fat, and a few punctate calcifications are present.

Thymolipoma. CT scan of the chest shows a large anterior mediastinal mass displacing the mediastinal vascular structures to the right and projecting into the left thorax. The tumor is composed of soft tissue and fat, and a few punctate calcifications are present.

Thymic cyst

On CT scans, a thymic cyst appears homogeneous with water attenuation. The attenuation may vary, depending on the contents of the cyst. High attenuation may be present if the cyst contains proteinaceous fluid or blood from hemorrhage. A neoplasm with cystic degeneration may closely mimic a thymic cyst; associated soft tissue attenuation may help in their differentiation.

Thymic rebound

After initiation of chemotherapy, CT scans may reveal a decrease in the size of the thymus. Rebound in the form of overgrowth occurs a few months after completion of chemotherapy. Criteria for rebound include an increase in size of greater than 50%, as compared to the baseline volume.

CT-guided biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy can be performed to differentiate between thymomas, lymphomas, and germ cell tumors, with the help of specific tissue staining and immunohistochemical techniques. (Greif J, Staroselsky AN, Gernjac M, Schwarz Y, Marmur S, Perlsman M, et al. Percutaneous core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of mediastinal tumors. [20, 21]

Degree of confidence

Chest CT scanning performed with and without contrast enhancement is clearly superior to routine radiography. A small thymic tumor can easily be missed on a chest radiograph, whereas CT scans distinctly delineate the tumor. In addition, enhancement often helps to clearly differentiate the mass from the surrounding vascular structures. This is helpful in planning surgery. [9, 10, 12, 13, 14]

On imaging studies, bilateral extension of the mass, absence of fat planes, and invasion of adjacent structures are indications of malignancy. MRI may show similar findings. The demonstration of encapsulation of the mass and the homogeneous enhancement of the capsule are indications of benign tumors; these structures are better imaged with CT scanning. MRI and CT scanning often complement each other and can facilitate preoperative diagnosis and staging of the thymus neoplasms.

In cases of lymphoid follicular hyperplasia, the thymus may not always appear enlarged; this may be overlooked on CT scans.

CT can be helpful in diagnosis and chracterization of thymoma. In one case series of 104 patients with myasthenia gravis, CT was found to be 88.5% sensitive and 77% specific for thymoma. [22]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI of the thymus is usually performed because of an incidental finding on the chest CT. In some cases, MRI is far superior to CT for thymus visualization and for differentiating it from the surrounding soft tissue. In healthy children younger than 5 years, MRI shows the thymus to have a quadrilateral shape and biconvex lateral contours. [23] In older children and adolescents, the thymus is triangular with straight, lateral margins. [24]

On T1-weighted images, the thymus appears homogeneous, with a signal intensity slightly greater than that of muscle; on T2-weighted images, the signal intensity is close to that of fat. The thymus can be seen on MRI in all adults. Signal intensity on T1 progressively decreases with advancing age because of fatty infiltration. However, the T2 relaxation times of the thymus do not change with aging. The thymus appears thicker on MRI than on CT in patients who are older than the second decade of life.

Mass lesions in the mediastinum can be differentiated from normal structures and fat on MRI. MRI produces excellent images in the mediastinum without contrast enhancement; with CT, however, contrast material is often needed to properly identify a mass and to avoid mistaking blood vessels for a mass lesion. Encasement or invasion of the vasculature, esophagus, and trachea and involvement of the pericardium, myocardium, and pleura are accurately detected with MRI.

Thymoma

On T1-weighted images, thymomas have medium signal intensity that is higher than that of skeletal muscle but lower than that of fat. On T2-weighted images, the signal intensity is close to or greater than that of fat. The mass often appears mostly homogeneous; areas of cystic degeneration appear as areas of variable signal intensity on T1-weighted images. This appearance is the result of variations in protein content or of hemorrhage; however, on T2-weighted images, thymomas appear bright. The hypointense fibrous septa often gives the mass a lobulated appearance.

Thymic carcinoma

Thymoma and thymic carcinoma have different MRI characteristics. Thymic carcinomas are hyperintense on both T1- and T2-weighted images, as compared to T1 hypointensity of thymomas, and may present with signal heterogeneity due to calcification, necrosis, or hemorrhage. Soft tissue components will enhance on postcontrast images, and invasion into adjacent structures may be more clearly delineated. MR can identify distant metastatic disease in the pleura, lymph node stations, and bones.

Thymic hyperplasia

Thymic hyperplasia and normal thymus share the same characteristics on MRI. In the case of thymolipoma, T1-weighted images have high signal intensity, which represents fat; strands of intermediate intensity represent thymic tissue.

Thymic cyst

T1-weighted images of thymic cysts have a low signal intensity; T2-weighted images have high signal intensity, which is consistent with the fluid component of the lesion. T1-weighted images naturally show high signal intensity if the cyst contains blood from hemorrhage or if it is rich in proteinaceous fluid.

Thymic lipoma

On T1-weighted spin-echo images, thymic lipomas have areas of high signal intensity because of their fat content; the signal intensity is similar to that of subcutaneous fat, with areas of intermediate signal intensity reflecting the presence of soft tissue. Although thymic lipomas can attain a large size, they invariably do not invade surrounding structures. However, they can cause mass effect on the surrounding structures because of their size.

Teratoma

Teratomas have various appearances on MRI, depending on the composition of the tumor. They commonly contain fat, which is of high signal intensity on T1-weighted images. Cystic changes may also be present; such changes have low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, but they have increased signal intensity on T2-weighting.

Seminoma

MRI often shows the inhomogeneous nature of seminomas.

Thymic carcinoid

MRI findings of thymic carcinoid tumors are nonspecific and are identical to those of thymomas. Thymic carcinoids tend to be large masses with irregular contours, without capsule. They have heterogeneous intensity on T2-weighted images and have heterogeneous enhancement and show local invasion on CT or MRI. A necrotic or cystic component is often seen in atypical carcinoids. These radiologic features mimic those of high-risk thymomas or thymic carcinomas. [25]

Lymphoma and residual tumor

The MRI signal characteristics of untreated lymphomas are different from those of treated lymphomas. Untreated lymphomatous tissue has high signal intensity, whereas a homogeneous, hypointense pattern is characteristic of inactive residual fibrotic masses in patients receiving successful therapy for lymphoma. A heterogeneous pattern with mixed hypointensity and hyperintensity is often seen in untreated nodular sclerosing Hodgkin disease. A heterogeneous pattern with mixed areas of low and high signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images is seen in lesions containing mixed fat (high signal intensity) and fibrous tissue (low signal intensity). This pattern is seen after treatment of patients with sterilized tumors. Positron emission tomography (PET) CT may play a role in assessing residual lymphoma. [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31]

Degree of confidence

With MRI of the thorax, motion artifacts may occur. Breathing motion and pulsation of the heart and great vessels can markedly degrade image quality. Hence, in general, fast imaging sequences and artifact reduction techniques must be used for MRI of the mediastinum and chest.

MRI is particularly useful when an intravenous contrast agent cannot be administered with CT because the patient is allergic to the agent.

MR has been noted to be superior to CT in the detection of thymoma, thymic cyst, or thymic hyperplasia, but it is still not clear if this is the case when differentiating thymic carcinoma, lymphoma, and germ cell tumor with MRI. [32]

Shen et al suggested that dynamic contrast enhancement with MRI may have a role in differentiating thymic carcinoma from thymic lymphoma. [33]

Nuclear Imaging

PET in thymic tumors

Uptake of FDG in the hyperplastic thymus is more common in patients with a known malignancy. [16] Thymic hyperplasia can be seen in sepsis, congenital heart disease, and after termination of steroid treatment, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. [34, 35, 36] FDG-PET/CT has been shown to provide useful information for differentiating epithelial tumors. [16, 17, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 37, 38] In a study by El-Bawab et al, FDG-PET/CT appeared to be more accurate than conventional imaging in distinguishing recurrent tumors in the mediastinum from fibrotic scar tissue in patients who underwent surgical excision of a thymoma, with all mediastinal recurrences (N=11) being correctly identified by FDG-PET/CT. [17]

Thallium-201 (201Tl) single photon emission CT (SPECT) scanning is useful for the evaluation of thymic lesions associated with myasthenia gravis, including lymphoid follicular hyperplasia and thymoma. [39]

On early images, 201Tl accumulation is more intense in thymomas than in the normal thymus and in lymphoid follicular hyperplasia. On delayed images, uptake is more intense in thymoma and in lymphoid follicular hyperplasia than in the normal thymus. Therefore, 201Tl SPECT scanning can be used to differentiate normal thymus from lymphoid follicular hyperplasia and thymoma in patients with myasthenia gravis. However, the use of thallium-201 SPECT is on the decline, and FDG-PET is being more widely used when available.

-

Fairly large thymus in an infant.

-

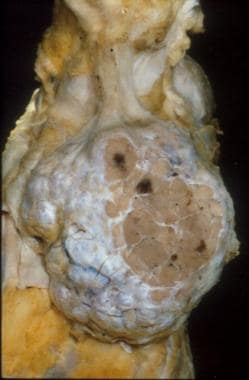

Gross appearance of a thymoma showing distinct multinodularity and scattered, focal cystic changes.

-

Normal thymus. The thymus is located anterior to the aortic arch, and sometimes 2 lobes can be seen. The thymus is prominent in newborns, occupying most of the anterior mediastinum. After puberty, fat progressively infiltrates the thymic tissue. At age 40 years, the thymus is nearly completely replaced with fat, and only slight residual nodular density of thymic tissue remains. A, Normally prominent thymus at age 7 months. B, Thymus in a 9-year-boy. C, Increasing fatty infiltration of the thymus noted in a 20-year-old man. D, The thymus has involuted and is atrophic in a 38-year-old man. Only a few nodular attenuations are visible.

-

Low-lying thymoma. Plain chest radiograph shows a mass lying against the right heart border.

-

Thymoma. CT scan shows a homogeneous thymic mass.

-

Malignant thymoma. Chest CT scan in a 61-year-old man with myasthenia gravis demonstrates a large, lobulated mass with punctate calcification in the anterior mediastinum; these findings are consistent with a thymoma.

-

Thymolipoma. CT scan of the chest shows a large anterior mediastinal mass displacing the mediastinal vascular structures to the right and projecting into the left thorax. The tumor is composed of soft tissue and fat, and a few punctate calcifications are present.

-

Thymic cystic teratoma. This thin-walled cystic mass contains a fat-fluid level.

-

Thymolymphoma. Chest radiograph shows a large, lobulated mediastinal mass.

-

Thymolymphoma. Contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrates a large, lobulated, soft tissue mass in the anterior mediastinum that posteriorly displaces the aorta and pulmonary artery.

-

Marked regression of the mass shown in the previous image after treatment.

-

Invasive thymoma. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a thymic mass with variable attenuations invading the adjacent mediastinum. Bilateral pleural effusions are also present, indicating pleural invasion.