Practice Essentials

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) account for nearly all (95%) primary testicular tumors. [1] The GCT line is fairly evenly split between seminomas (45%) and nonseminomas (50%) (see the images below). Of the nonseminomas, mixed GCTs are most common (40%). Teratomas and teratocarcinomas are considered malignant in adults and constitute 30% of nonseminomatous lesions. The embryonal cell tumor is the classic pure-cell, nonseminomatous tumor and is relatively uncommon (20%). Choriocarcinoma represents the most lethal but least common (1%) nonseminomatous type. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Primary testicular tumors are the most common solid malignant tumor in men 20 to 35 years of age in the United States. It is estimated that in 2020 in the United States, 9610 new cases of testicular cancer will be diagnosed in men, and 440 men will die of the disease. [7, 6]

In patients with localized testicular cancer, painless swelling or a nodule in one testicle is the most common presenting sign. A dull ache or heavy sensation in the lower abdomen could be the presenting symptom. Patients with disseminated disease can present with manifestations of lymphatic or hematogenous spread.

The key anatomic factor in testicular cancer is that the lymphatic drainage of the scrotum is into the lower legs, while the lymphatic drainage of the testicles is into the abdomen and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. For this reason, transscrotal testicular biopsy is not recommended. In addition, scrotal masses that do not involve the testicle are rarely malignant. [8]

Patients with stage 1 or 2 (2A or 2B) testicular cancer have a long-term, disease-free survival rate greater than 95%; in patients with bulky retroperitoneal nodes and/or pulmonary or visceral metastasis, this rate is 60-80%.

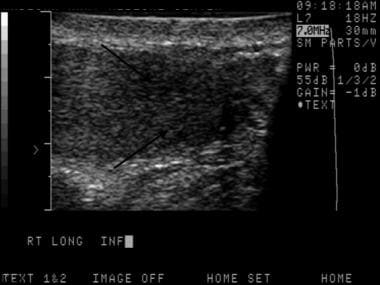

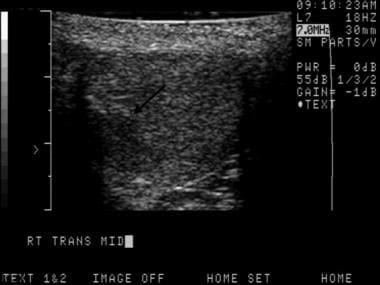

The depiction here is classic for a seminoma. Testicular malignancies appear as a hypoechoic mass in the vast majority of cases.

The depiction here is classic for a seminoma. Testicular malignancies appear as a hypoechoic mass in the vast majority of cases.

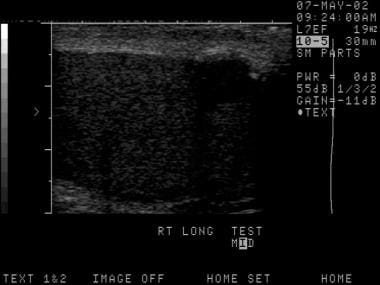

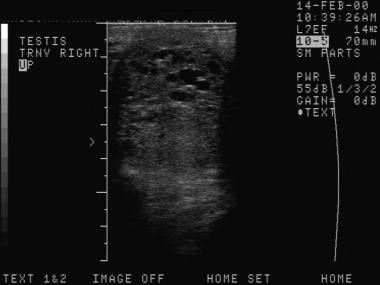

This is another seminoma. On sonograms, a seminoma is often more homogeneous than nonseminomatous cancers.

This is another seminoma. On sonograms, a seminoma is often more homogeneous than nonseminomatous cancers.

Yolk sac tumors, which are also known as endodermal sinus tumors, are the most common prepubertal GCTs. They may be benign, but most often, they are malignant. Most affected patients require surgery and chemotherapy because of the aggressive nature of the tumors, but the overall prognosis is excellent.

Among nongerminal testicular tumors, stromal Leydig cell tumors and Sertoli cell tumors constitute the remaining 5% of primary testicular tumors; these are rare tumors that are malignant in only about 10% of the cases.

Lymphoma, leukemia, and melanoma are the most common malignancies that metastasize to the testicle. [9]

The exact etiology of testicular cancer is not clearly defined; however, recent data show a dramatically increasing incidence rate in developed countries, which has lead to increasing interest in factors affecting hormonal balance, with speculated association to a variety of endocrine disruptors. [10]

Preferred examination

Ultrasonography is the standard imaging technique used to identify testicular carcinoma. It has a high sensitivity, but it must be combined with physical examination to achieve the best specificity. More than 95% of testicular parenchymal abnormalities are identifiable on routine sonograms, but several other lesions commonly mimic testicular cancer. Ultrasonography is more specific in the presence of a palpable mass. Nonpalpable intratesticular lesions larger than 1 cm are unlikely to be malignant. The false-negative rate for ultrasonographic identification of testicular lesions is extremely low. [11, 2, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend initial staging for both seminomas and nonseminoma germ cell tumors with contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. [13, 4] Ultrasound has been shown to have greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity for detecting testicular malignancy. [13, 15, 16] Contrast-enhanced ultrasound and elastography have also been studied as tools for assessing testicular masses as adjuncts to traditional gray scale and color Doppler ultrasound assessment. [13, 16]

The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (in conjunction with the American College of Radiology, Society for Pediatric Radiology, and Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound) have published guidelines on testicular and extratesticular examination. Indications include the following [17] :

-

Evaluation of scrotal pain, including but not limited to testicular trauma, ischemia/torsion, and infectious or inflammatory scrotal disease.

-

Evaluation of palpable inguinal, intrascrotal, or testicular masses.

-

Evaluation of scrotal asymmetry, swelling, or enlargement.

-

Evaluation of potential intrascrotal hernias.

-

Detection/evaluation of varicoceles.

-

Evaluation of male infertility.

-

Follow-up of prior indeterminate scrotal ultrasound findings.

-

Localization of nonpalpable testes.

-

Detection of occult primary tumors in patients with metastatic germ cell tumors or unexplained retroperitoneal adenopathy.

-

Follow-up of patients with prior primary testicular neoplasms, leukemia, or lymphoma.

-

Evaluation of abnormalities noted on other imaging studies (including but not limited to CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography [PET]).

CT scan imaging is routinely performed as part of the initial staging process, but it is not sensitive or specific enough to be useful in evaluating undiagnosed testicular masses. [18] CT remains the modality of choice for assessing retroperitoneal lymph nodes. [13, 14] In cases of seminoma, the NCCN recommends staging with chest CT to assess for thoracic adenopathy and pulmonary metastasis if retroperitoneal metastasis is detected by abdominal CT. [13, 15, 3]

MRI of the scrotum offers higher sensitivity and specificity than ultrasonography in the diagnosis of testicular cancer, but its high cost does not justify its routine use for diagnosis. [19] Increased signal intensity in the testicle is seen on T2-weighted images of testicular malignancies, but it is not specific for the disease. [20, 21, 22]

MRI can be useful as an adjunctive study if ultrasound findings are equivocal and can help evaluate tumors on the basis of T1 and T2 characteristics, which allows differentiation of soft tissue, fat, and fluid. Also, T1-weighted pre- and post-contrast sequences can assess tumor enhancement. Diffusion-weighted imaging can assess lesions at a more molecular level. [13, 20, 21, 3]

Radiographs are not useful in the detection of testicular cancer, but chest x-ray is often used to surveil for metastatic disease.

Epidemiology

Primary testicular tumors are the most common solid malignant tumor in men 20 to 35 years of age in the United States. The age-adjusted incidence rate for testicular cancer has been estimated at 5.5 cases per 100,000 men per year. Almost 8,000 new cases present each year, but the death rate is relatively low at 370 deaths per year. The median age of diagnosis for cancer of the testes in the United States has been reported to be approximately 33 years, and for death, 40 years.Twenty percent of patients present with metastatic disease. [1, 23, 24]

With regard to racial distribution in the United States, testicular cancer has a higher incidence in whites, with 6.6 cases per 100,000 men per year, compared with 4.7 cases per 100,000 men per year for Latinos, 4.5 cases per 100,000 men per year for Native Americans, 1.9 case per 100,000 men per year for Asians, and 1.4 cases per 100,000 men per year for blacks. [23, 7]

Testicular cancer rates in developed European countries are slightly higher than in the United States, at 8-9 cases per 100,000 men per year. Rates are lowest in Asian and African populations, at less than 1 case per 100,000 men per year. [25] A

AUA guidelines

The American Urological Association (AUA) has provided the following imaging recommendations [5] :

-

In patients with newly diagnosed GCT, clinicians must obtain a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast, or with MRI if there are contraindications to CT.

-

In patients with newly diagnosed GCT, clinicians must obtain chest imaging.

-

In the presence of elevated and rising post-orchiectomy markers (hCG and AFP) or evidence of metastases on abdominal/pelvic imaging, chest x-ray, or physical exam, a CT chest should be obtained.

-

In patients with clinical stage I seminoma, clinicians should preferentially obtain a chest x-ray over a CT scan.

-

In patients with a non-seminoma GCT, clinicians may preferentially obtain a CT scan of the chest over a chest x-ray and should prioritize CT chest for those patients recommended to receive adjuvant therapy.

-

In patients with newly diagnosed GCT, clinicians should not obtain a positron emission tomography scan for staging.

-

Patients should be assigned a TNM-s category to guide management decisions.

Computed Tomography

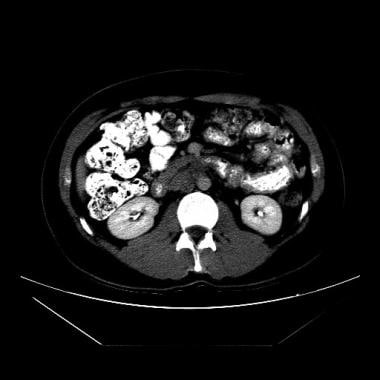

CT scan imaging is routinely performed as part of the initial staging process, but it is not sensitive or specific enough to be useful in evaluating undiagnosed testicular masses. [18] Chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT scan studies are indicated for the evaluation of retroperitoneal and mediastinal metastases.

CT scanning of the chest is especially useful when mediastinal or parenchymal lung disease caused by testicular cancer is suspected. This modality or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also indicated in patients with neurologic signs or symptoms.

The most common site of disease recurrence is the retroperitoneum; thus, CT scanning is the best tool to detect recurrence.

Lymphoma can be difficult to distinguish from metastatic testicular cancer. Use tissue sampling from the abnormal testicle to make this distinction.

(See the image below.)

Both computed tomography (CT) scanning and ultrasonography have been used to search for metastatic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, but CT scanning is more commonly used.

Both computed tomography (CT) scanning and ultrasonography have been used to search for metastatic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, but CT scanning is more commonly used.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI of the scrotum offers higher sensitivity and specificity than ultrasonography in the diagnosis of testicular cancer, but its high cost does not justify its routine use for diagnosis. [19] Increased signal intensity in the testicle is seen on T2-weighted images of testicular malignancies, but it is not specific for the disease. [20, 21, 22]

MRI can be useful as an adjunctive study if ultrasound findings are equivocal and can help evaluate tumors on the basis of T1 and T2 characteristics, which allows differentiation of soft tissue, fat, and fluid. Also, T1-weighted pre- and post-contrast sequences can assess tumor enhancement. Diffusion-weighted imaging can assess lesions at a more molecular level. [13, 20, 21, 3]

There are ongoing studies that suggest diffusion-weighted MRI sequences are similar to CT in detecting repropertoneal metastatic disease. [26]

MRI has been shown to be successful in differentiating between seminomatous and nonseminomatous tumors. Testicular tumors are isointense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images, but nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT) demonstated more heterogeneity on T2 sequences, which is likely because of increased areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Seminomatous tumors demonstrate a lower apparent diffusion coefficient. [27]

Ultrasonography

Testicular ultrasonography is used to determine the location of a palpable mass when testicular cancer is suspected. Generally, palpable extra-testicular lesions are benign. On the other hand, intratesticular masses, especially if they are palpable, are likely to be malignant and must be surgically explored. Therefore, ultrasonography is useful for localizing palpable abnormalities and to triage them for surgical repair when indicated. [28] There is general consensus that an ultrasonographic finding of a solid or mixed cystic and solid intratesticular mass is an indication for surgical exploration.

(See the images below.)

The depiction here is classic for a seminoma. Testicular malignancies appear as a hypoechoic mass in the vast majority of cases.

The depiction here is classic for a seminoma. Testicular malignancies appear as a hypoechoic mass in the vast majority of cases.

Compared with other types of tumors, mixed germ-cell tumors are more likely to have cystic areas and calcifications scattered within the tumor.

Compared with other types of tumors, mixed germ-cell tumors are more likely to have cystic areas and calcifications scattered within the tumor.

This is another seminoma. On sonograms, a seminoma is often more homogeneous than nonseminomatous cancers.

This is another seminoma. On sonograms, a seminoma is often more homogeneous than nonseminomatous cancers.

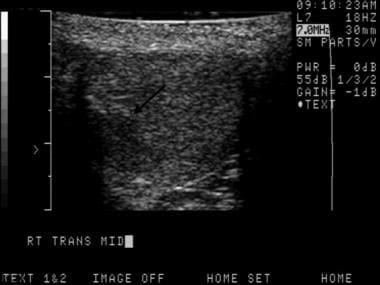

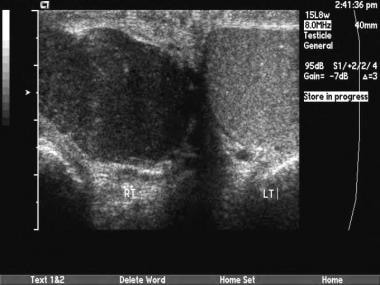

This is a seminoma. Occasionally, testicular tumors occur at a more advanced stage. If the entire testicle is involved, comparison with the normal side may show diffusely decreased echogenicity. Sometimes, epididymal invasion can be noted on sonograms.

This is a seminoma. Occasionally, testicular tumors occur at a more advanced stage. If the entire testicle is involved, comparison with the normal side may show diffusely decreased echogenicity. Sometimes, epididymal invasion can be noted on sonograms.

The examination is usually performed with a high-frequency linear transducer to compare the echotexture of the 2 testicles for areas of heterogeneity. Testicular cancers are hypoechoic relative to the surrounding parenchyma in about 95% of cases. Published findings suggest that seminomas are often more homogeneously hypoechoic and that nonseminomatous lesions are often more cystic, with interspersed areas of calcification. [29, 30] (For scans of malignant tumors of the testicle, see the images below.)

The tumor tissue type cannot be reliably differentiated solely by its ultrasonographic appearance. Commonly, seminomas are well defined within the tunica albuginea and homogeneously hypoechoic. Embryonal cell cancers typically are hypoechoic, with interspersed cystic components. Teratomas and choriocarcinomas are often heterogeneous with multiple internal calcifications present. Stromal cell tumors (eg, Leydig and Sertoli cell tumors) are generally well defined and hypoechoic, but calcifications are frequently found. Lymphoma and leukemia of the testicle generally present as an ill-defined, diffuse process of decreased echogenicity.

When multiple lesions are present, the differential diagnosis should be expanded to include metastatic processes, such as leukemia and lymphoma, and inflammatory processes, such as sarcoid. Testicular lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose when both testes are homogeneously hypoechoic.

Testicular microlithiasis (≥5 or more microcalcifications within a testicle) results from concentric cores of calcification of intrasubstance collagen fibers. Case studies of patients with testicular tumors suggest a high rate of microlithiasis, but prospective evaluations of patients with microlithiasis have failed to demonstrate more than a minimal increase in the frequency of such tumors. Annual ultrasonographic screening of patients with microlithiasis has been suggested by some authors, but prospective studies have failed to demonstrate a positive cost-benefit ratio at this time. [31, 32, 33]

Azzopardi tumor is the name used for a presumed "spontaneously burned out" tumor, wherein malignant cells spontaneously necrose and calcify, perhaps related to outgrowing the blood supply.

False positives/negatives

False-negative results are most common in the infiltrative malignant processes. When a condition such as leukemia or lymphoma causes bilateral diffusely decreased echogenicity, the infiltrative malignant process can be difficult to recognize.

False-positive results are seen in a variety of conditions. Dilated rete testes can be masslike, and they can simulate a predominantly cystic mass. The imaging characteristics of epidermoid tumors can be indistinguishable from those of germ cell lesions. Cho et al reported that the classic appearance of an epidermoid is a heterogeneous mass, possibly with concentric hyperechoic and hypoechoic layers forming a ring. [34] The epidermoid is often avascular. An abscess or phlegmon of the testicle is hypoechoic and often associated with increased vascularity. Testicular infarction can present as ill-defined decreased echogenicity in a testicle, suggesting a diffusely infiltrative malignant process.

A troublesome scenario can occur when a patient presents with a history of trauma and the sonogram shows a hypoechoic focus presumed to be a hematoma. Distinguishing a hematoma from a testicular tumor can be impossible on the initial images. Because such tumors can be detected after incidental trauma, ultrasonographic follow-up of suspected hematomas is recommended to ensure their complete resolution.

(See the images below.)

Dilated rete testes can mimic a cystic neoplasm, but they are usually elongated on orthogonal views and clearly located in the testicular mediastinum.

Dilated rete testes can mimic a cystic neoplasm, but they are usually elongated on orthogonal views and clearly located in the testicular mediastinum.

PET and PET-CT

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria note that FDG-PET scans have a slightly higher sensitivity than CT, but their role in staging testicular cancer has not been determined. FDG-PET may play a role in follow-up of higher-stage seminoma after chemotherapy. [35] .

In some studies, F18-FDG PET/CT findings have been shown to change the patient's initial CT-based staging. The highest concentration of FDG has been seen in seminomas, and the lowest concentration of FDG has been seen in mixed tumors. [13]

PET is very useful in evaluating the response to chemotherapy, especially in pure seminoma. It can be used in nonseminomatous malignancy, but the specificity is decreased because of false negative results in mature teratomas. [36]

Retoperitoneal lymph node dissection is to be considered in patients with PET-positive residual masses, which are 3 cm or greater. In patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, the cut-off size is much lower, at 1 cm. [1]

According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, PET or PET-CT plays no role in the initial staging of testicular cancer. [37]

What's New?

Much of the recently published studies center on molecular and cell biology. A vary large large number of biomarkers of testicular cancer have been proposed. These reports are relatively rudimentary at this time, with a high number of markers described in the literature. In gonadal development, primordial germ cells are found in the embryo (week 5-6) and develop through a specific sequence of embryonic tissue to mature as testicles. Originating in the epiblast, they migrate to the genital ridge to become mature testicles. Extratesticular tumors are linked to this sequence and have a higher mutation burden in comparision with testicular tumors. [15, 38, 39, 40, 41, 26, 27, 42]

It is well accepted that testicular germs cell tumors are associated with hypertriploid genetics. Specifically, there is increased genetic material in the 12p chromosome arm in almost every case, and additional material from chromosomes 7 and 8 has been found in over 70% of cases. In non-seminomatous malignancy, chromosome 19 and 22 material appears more frequently than in seminoma. The TP53 mutation is most common in nonseminomatous tumors and extragonadal tumors.

MicroRNAs are better markers for testicular tumors than α-fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin subunit-β (β-HCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Follow-up values can be used to predict relapse. mMiR-371a-3p is the most sensitive and specific (>90%). MicroRNAs are not useful in mature tumors.

Studies of mean nonsynonymous mutational burden (TMB) confirm that lower values are seen in tumors with an embryonal origin, and testicular germ cell tumors have a lower burden as compared to most adult solid tumors. TMB is lower in patients who are younger at initial diagnosis and higher in recurrences after chemotherapy, especially in platinum-resistant lines.

Placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), a membrane-bound protein that is expressed in fetal germ cells, is elevated in half of all seminomas.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating free DNA (cfDNA) can be dectected in the serum through apoptosis and tumor necrosis, but protocols for analysis have not been validated.

Using genetic tumor markers, it appears possible to predict the risk of recurrent disease, to identify disease burden, and to select chemotherapy regimens. The KIT and TP53 mutations are associated with platinum resistence. Abnormal gain in the 6q21-q24 regions predicts poor response to chemotherapy. The specific abnormalites appear to be multifactorial and will require ongoing analysis.

Testicular Cancer and the Environment

Elevated titers of anti-EBV antibodies strongly link cancer disease to previous viral exposure. Exposure to pesticides has been linked to testicular cancer in some studies, but comparision of formulations and doses across studies limits the correlation. Firefighters show higer risk for testicular cancer, but the exact mechanism has not been elucidated (heat exposure versus toxin exposure). Because cryptorchidism increases the risk for testicular cancer, endocrine disruptors are suspected for increased rates of testicular cancer, but the specific etiology has not been confirmed. Study of endocrine disruptors is complicated by the wide variety of substances that have been implicated. Chlordane serum levels have been noted to be elevated before and after the diagnosis of testicular cancers. [41]

-

The depiction here is classic for a seminoma. Testicular malignancies appear as a hypoechoic mass in the vast majority of cases.

-

Testicular infarction can mimic an infiltrative tumor.

-

Compared with other types of tumors, mixed germ-cell tumors are more likely to have cystic areas and calcifications scattered within the tumor.

-

This is another seminoma. On sonograms, a seminoma is often more homogeneous than nonseminomatous cancers.

-

This is a mixed germ cell tumor. Testicular cancers can be ill-defined and subtle.

-

Both computed tomography (CT) scanning and ultrasonography have been used to search for metastatic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, but CT scanning is more commonly used.

-

Dilated rete testes can mimic a cystic neoplasm, but they are usually elongated on orthogonal views and clearly located in the testicular mediastinum.

-

Testicular sarcoid can mimic seminoma when it presents as a solid-appearing testicular mass.

-

This is a seminoma. Occasionally, testicular tumors occur at a more advanced stage. If the entire testicle is involved, comparison with the normal side may show diffusely decreased echogenicity. Sometimes, epididymal invasion can be noted on sonograms.

-

This is a seminoma. Sometimes epididymal invasion can be noted on sonograms.

-

Testicular cancer is not typically hypervascular.

-

Testicular epidermoids can mimic solid malignancies.