Practice Essentials

Temporal arteritis, or giant cell arteritis (GCA), is a common systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology. In 1890, Hutchinson originally described the condition as inflamed and swollen temporal arteries. In 1932, Horton expanded the definition. In general, temporal arteritis can be thought of as a vasculitis involving medium-to-large arteries originating from the aorta. Although it was originally believed to be a rare entity, it is more commonly recognized today. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Patients may present with a variety of symptoms; the most common include headache, jaw claudication, fatigue, night sweats, and visual disturbances. Temporal arteritis may have serious systemic, neurologic, and ophthalmic consequences, as it may lead to impaired vision and blindness. Definitive diagnosis is based on histopathologic analysis of a superficial temporal artery biopsy, which requires a small surgical procedure often under local anesthesia. Arterial duplex ultrasound (US) may serve as a valuable diagnostic addition to prevent unnecessary surgical procedures and can even substitute for biopsy in patients for whom surgery is not an option. [7]

Temporal arteritis is an immunologic disorder that most often affects the elderly population. It frequently occurs in association with other rheumatologic diseases of the elderly (eg, polymyalgia rheumatica). Symptoms of temporal arteritis overlap with other symptoms of commonly occurring diseases in this population. [8]

Dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) is a very rare disease that is characterized by abnormal vascular communication between arteries and veins in the dura mater. Patients frequently present with intracranial hemorrhage. Common presenting symptoms include headache and seizures. Given that these diseases have a different prognosis but a similar presentation, it is important to ensure that there is no dAVF in a patient with suspected temporal arteritis. [9]

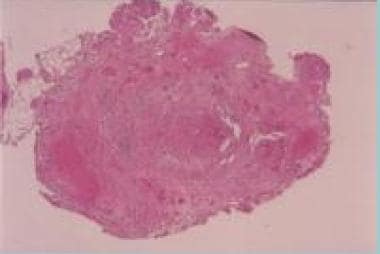

(See the images below.)

Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained superficial temporal artery biopsy specimen, cross section. The hallmark histologic features of GCA shown here include intimal thickening with luminal stenosis, mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate with media invasion and necrosis, and giant cell formation in the media

Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained superficial temporal artery biopsy specimen, cross section. The hallmark histologic features of GCA shown here include intimal thickening with luminal stenosis, mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate with media invasion and necrosis, and giant cell formation in the media

Preferred examination

The diagnosis of temporal arteritis (GCA) is made by using a combination of temporal artery US, clinical findings, and blood tests. Temporal artery biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, is not always performed but is sometimes needed for histopathologic confirmation. [10] A negative biopsy finding does not exclude the diagnosis.

No radiologic finding is specific for the diagnosis of temporal arteritis alone. Imaging studies are helpful in determining the extent of involvement and in identifying unsuspected areas of involvement. [11]

Angiography can be used when biopsy results are negative, or it can be used to help guide biopsy by demonstrating areas of abnormality. [12, 13] When performed, angiography is typically directed at the large branch vessels of the proximal aorta and extracranial carotid branch vessels. The temporal arteries are depicted well in almost 90% of patients. In patients with proximal artery stenoses, angioplasty can be used in addition to corticosteroid therapy for symptomatic relief. [14]

Although angiography is one of the best-studied techniques, it is invasive and inconvenient and has risks associated with the use of contrast material. As a result, less-invasive procedures for evaluating the arterial anatomy have been sought. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) has results comparable to those of angiography in evaluating medium to large vessels. In some reported cases, MRA has successfully depicted disease in the temporal arteries. However, MRA is limited in evaluating smaller vessels, and imaging artifacts may result in false-positive results. In addition, larger vessels with mildly thickened walls can be missed. As the sensitivity of MRA continues to improve, it will likely become a more realistic method for evaluating stenotic lesions attributed to temporal arteritis. [15, 16, 17]

Studies have demonstrated the benefit of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. [18, 19, 20, 21] Characteristic changes, including stenoses and occlusions of temporal artery segments and a dark halo around the vessel, have been reliably observed in patients with temporal arteritis. Doppler flow studies have also been performed, with promising results. [22] However, ultrasonography may not depict minor vascular changes or diseased vessels, such as intrathoracic vessels, that are not amenable to ultrasonography.

A study of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning evaluated 18F-glucose uptake and demonstrated a sensitivity of 56%, a specificity of 98%, and a positive predictive value of 93% for the diagnosis of GCA or polymyalgia rheumatica. [23]

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare endocrine emergency that is characterized by a sudden increase in pituitary gland volume secondary to acute ischemic infarction or hemorrhage of the pituitary gland, usually in the presence of a pituitary adenoma. Pituitary apoplexy can present as severe headache without ophthalmoplegia or impairment of consciousness. It may be mistaken for temporal arteritis. CT results may be normal, so MRI is the diagnostic imaging of choice. [24]

EULAR guidelines

European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines in clinical practice, published in 2018, include the following recommendations on imaging in GCA [25] :

-

In patients with suspected GCA, early imaging is recommended to complement the clinical diagnostic criteria, assuming high expertise and prompt availability of the imaging technique. Imaging should not delay initiation of treatment.

-

In patients in whom there is a high clinical suspicion of GCA and a positive imaging study, the diagnosis of GCA may be made without biopsy or further imaging. In patients with a low clinical probability and a negative imaging result, the diagnosis of GCA can be considered unlikely. In all other situations, additional efforts towards a diagnosis are necessary.

-

Temporal artery US, with or without axillary artery US, is recommended as the first imaging modality in patients with suspected GCA with predominantly cranial manifestations (eg, headache, visual symptoms, jaw claudication, temporal artery swelling and/or tenderness). A non-compressible ‘halo’ sign is the US finding most suggestive of GCA.

-

If US is not available or the results are inconclusive, high-resolution MRI of cranial arteries to investigate mural inflammation may be used as an alternative for diagnosis of GCA.

-

CT and PET are not recommended for the assessment of inflammation of cranial arteries.

-

US, PET, MRI, and/or CT may be used for detection of mural inflammation and/or luminal changes in extracranial arteries to support the diagnosis of large-vessel GCA. US is of limited value for assessment of aortitis.

-

Conventional angiography is not recommended for the diagnosis of GCA, as it has been superseded by the previously mentioned imaging modalities.

-

In patients with GCA in whom a flare is suspected, imaging might be helpful to confirm or exclude it. Imaging is not routinely recommended for patients in clinical and biochemical remission.

-

MRA, CTA, and/or US may be used for long-term monitoring of structural damage in patients with GCA, particularly to detect stenosis, occlusion, dilatation, and/or aneurysms. The frequency of screening as well as the imaging method applied should be decided on an individual basis.

-

Imaging examination should be done by a trained specialist using appropriate equipment, operational procedures and settings. The reliability of imaging, which has often been a concern, can be improved by specific training.

Computed Tomography

Thickening of the arterial walls, stenosis, or occlusion may be demonstrated on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans. However, CT scanning commonly fails to depict mild inflammatory changes in the vessels. CT is not useful for the evaluation of small-vessel disease. In older persons, disease processes such as atherosclerotic disease are far more common than temporal arteritis and may result in similar CT findings.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in temporal arteritis (giant cell arteritis [GCA]) include loss of the normal flow void in affected vessels from occlusion or slow flow associated with disease. Enhancement of the arterial wall may be observed after the administration of gadolinium-based contrast material. [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31] MRA may also demonstrate stenoses, irregularity of the vessel wall, and beading or thickening of the vessel wall.

Contrast-enhanced MRI to diagnose GCA was found, in one study, to have a sensitivity of 78.4% and a specificity of 90.4%. In patients in whom temporal artery biopsy was performed, sensitivity and specificity of MRI were 88.7% and 75%, respectively. The authors noted that sensitivity of MRI probably decreases after more than 5 days of systemic corticosteroid therapy, so that imaging should not be delayed. [32]

In a study of deep temporal artery and temporalis muscle involvement in patients with GCA, MRI visualized changes in both the temporalis muscle and the deep temporal artery, and moderate correlation of clinical symptoms with MRI results was observed. Two radiologists assessed the images. They found temporalis muscle involvement in 19.7% and 21.3 % of GCA patients, and it occurred bilaterally in 100%. Specificities were 92% and 97%, and sensitivities were 20% and 21%. Deep temporal artery involvement was found in 34.4% and 49.2% and occurred bilaterally in 80% and 90.5%; specificities were 84% and 95%, and sensitivities were 34% and 49%. [29]

In a prospective study of vasculitic changes in patients with GCA assessed by 3T MRI, vessel wall enhancement of intradural arteries, mainly the internal carotid artery (ICA), was regularly found. In this study, by Siemonsen et al, 2 independent observers found clear vessel wall enhancement of superficial extracranial and intradural internal carotid arteries in 16 and 10 patients, respectively. Slight vessel wall enhancement of the vertebral arteries was seen. Of 9 patients with GCA with vessel occlusion or stenosis, 2 presented with cerebral ischemic infarcts. Vessel occlusion or stenosis sites coincided with the location of vessel wall enhancement of the vertebral arteries in 4 patients and of the intradural ICA in 1 patient. [33]

MRI commonly will miss mild inflammatory changes in vessels. MRI is not useful for the evaluation of small-vessel disease. In the elderly, disease processes such as atherosclerotic disease are far more common than temporal arteritis and may result in similar MRI findings.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). These complications have occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage kidney disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA scans.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography can be used to evaluate small vessels, such as the temporal arteries. Findings include stenoses and occlusion of the vessels. A characteristic hypoechoic halo has been described as surrounding the affected vessel; the halo disappears with effective corticosteroid therapy. Ultrasonography is also useful in guiding biopsy. [34] Ultrasonography cannot be used to evaluate vessels such as intrathoracic arteries, which are more amenable to angiography and MRI. Findings may be negative in patients with minimal involvement of the temporal arteries. In addition, atherosclerotic disease involving the temporal arteries may have an appearance similar to that of temporal arteritis, although this is unusual.

The prospective Temporal Arteries in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis (TABUL) study, which included an ultrasound training program for diagnosing GCA, analyzed 381 patients who underwent both ultrasound and TAB within 10 days of starting treatment for suspected GCA, and found that the sensitivity of TAB was 39% (95% confidence interval (CI), 33% to 46%), which was significantly lower than previously reported and inferior to that of ultrasound (54%; 95% CI, 48% to 60%). However, TAB had 100% specificity (95% CI, 97% to 100%), versus 81% (95% CI, 73% to 88%) for ultrasound. [35]

The TABUL authors noted that performing ultrasound scans in all patients with suspected GCA and performing biopsies only on negative cases increased the sensitivity of ultrasound to 65% while maintaining specificity at 81%, reducing the need for biopsies by 43%. Furthermore, strategies that combined clinical judgment with testing showed sensitivity and specificity of 91% for TAB and 81% for ultrasound, and specificity of 93% and 77%, respectively. Cost-effectiveness favored ultrasound, with both cost savings and a small health gain. [35]

Temporal arteritis is a serious condition requiring immediate treatment to prevent complications. It can be difficult to diagnose, especially in emergency department (ED) settings, where ophthalmology and rheumatology services may be unavailable. Temporal artery ultrasound (TAUS) is a valuable tool for diagnosing temporal arteritis. In the ED, TAUS can be used to quickly rule out temporal arteritis while avoiding unindicated steroid treatment, which can cause serious morbidity in elderly patients. [36] Temporal artery biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing temporal arteritis. However, TAUS is a fast and noninvasive procedure that may provide a supplement or serve as an alternative to biopsy. [37]

In a 2023 single-center retrospective study of patients with temporal arteritis, relapse was defined as increased temporal arteritis disease activity requiring treatment escalation. In this real-world setting, relapse occurred at a wide range of glucocorticoid doses and was not predicted by axillary artery involvement. Patients with higher halo count (HC) at diagnosis were significantly more likely to relapse, but significance was lost on excluding those with an HC of zero. HC is feasible in routine care and may be worth incorporating into future prognostic scores. Further research is required to determine whether confirmed temporal arteritis patients with negative TAUS represent a qualitatively different subphenotype within the disease spectrum. [38]

Nuclear Imaging

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning has been used to evaluate unusual involvement that cannot be evaluated by means of surgical biopsy or ultrasonography. PET scanning cannot be used to distinguish between the increased uptake observed with temporal arteritis and that observed in polymyalgia rheumatica.

FDG PET/CT is increasingly being used to diagnose inflammation of the large arteries in GCA. In one study, the number of vascular segments with diffuse FDG uptake pattern was significantly higher in GCA patients who were not receiving glucocorticoids. [39]

Angiography

Angiography is an invasive test with inherent risks associated with the procedure and with the administration of contrast material. Findings consist of the involvement of small to moderate vessels. Angiography can demonstrate areas of constriction, beading, and microaneurysm formation that are fairly specific for temporal arteritis (giant cell arteritis). The occlusion of vessels and stenoses that are amenable to treatment may also be observed.

The most common sites for abnormalities to occur anatomically and on imaging studies are in the distal subclavian, proximal axillary, brachial, brachiocephalic, and femoral arteries. Atherosclerotic disease is a common finding in the older population; however, narrowings observed with atherosclerotic disease are typically short, segmental, and irregular, whereas stenoses in temporal arteritis are smooth, long, segmental, and tapered.

Similar findings may be observed in patients with Takayasu arteritis and in those with atherosclerotic disease. Temporal artery biopsy is more definitive than angiography, and it can be guided by the arteriographic findings.

False-negative results may occur in a few patients in whom the temporal arteries are not well visualized.

-

Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained superficial temporal artery biopsy specimen, cross section. The hallmark histologic features of GCA shown here include intimal thickening with luminal stenosis, mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate with media invasion and necrosis, and giant cell formation in the media

-

Lumbar angiogram showing stenosis and occlusion of femoral artery branches due to vasculitis.