Practice Essentials

Sinusitis is an inflammation of the mucosal lining of the paranasal sinuses. As the mucosa of the sinuses is continuous with that of the nose, rhinosinusitis is a more suitable term. [1, 2, 3, 4] Sinusitis can be subdivided into acute, subacute, chronic, and recurrent disease. Acute sinusitis is defined as disease lasting less than 1 month. Subacute disease lasts 1-3 months, and chronic sinusitis lasts longer than 3 months and is generally related to suboptimally treated acute or subacute disease. Acute and subacute sinusitis are treated medically, whereas chronic sinusitis may require surgical intervention. [5]

There are several types of fungal sinusitis. There are 3 types of noninvasive fungal sinusitis (fungal ball, saprophytic fungal sinusitis, and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis) and 3 types of invasive fungal sinusitis (acute invasive rhinosinusitis, chronic invasive rhinosinusitis, and granulomatous invasive sinusitis). [6, 7]

Approximately 0.5 to 2% of patients with sinusitis will have or develop bacterial sinusitis. Pott puffy tumor is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of bacterial sinusitis consisting of subperiosteal abscess and osteomyelitis of the frontal bone. It is best diagnosed by CT with IV contrast or MRI and treated with early broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical intervention. Symptoms can include headache, periorbital swelling, swelling of the forehead, purulent drainage, cutaneous fistulas, altered mental status, and cranial nerve deficits. [8, 9]

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) has revolutionized the treatment of sinusitis. The therapeutic benefits of FESS have helped a large number of patients with chronic sinus disease. [10, 11]

Obstruction of the draining pathways of the sinuses is now thought to be the main cause of sinusitis. Examples of these pathways include the ostia of the maxillary sinuses and the hiatus semilunaris, where the anterior group of paranasal sinuses drains. Clearance of this obstruction is the aim of endoscopic surgery.

Imaging has also progressed with FESS, and computed tomography (CT) scanning can now demonstrate the sinus anatomy and patterns of sinusitis in exquisite detail before surgery. [12, 13]

Imaging modalities

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the examination of choice in sinusitis, particularly in cases of chronic sinus disease, providing excellent detail of sinus anatomy. However, CT is usually not useful in acute sinusitis, as diagnosis in acute cases is primarily based on clinical findings. Good anatomic definition is desirable before surgical intervention. [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]

Coronal CT imaging is the preferred initial procedure. Bone-window views provide excellent resolution and good definition of the complete ostiomeatal complex and other anatomic details that play a role in sinusitis. In addition, the coronal view is best correlated with findings from sinus surgery, with anatomy and pathology visualized in a plane almost identical to that seen by the endoscopist.

CT provides an excellent anatomic display of soft-tissue attenuation. This depiction includes fluid levels and polypoid masses within the normally air-filled cavities of the sinuses, nasal cavity, and postnasal space. Most important, disease extending beyond the bony perimeters of the sinuses into the adjacent soft tissue of the orbit, [20] brain, and infratemporal fossa can be imaged.

In general, nonenhanced CT scans suffice in cases of uncomplicated sinusitis. Multisection CT seems to have the potential to replace primary coronal CT of the paranasal sinuses without any loss of image quality, and it may even improve the overall diagnostic value. However, the doses of radiation may still have to be reduced.

Although CT scanning provides an excellent anatomic display, it generally does not help in predicting the histologic nature of the pathologic process. On CT scans, it is difficult or impossible to differentiate tumor tissue from retained fluid in sinuses, where the drainage of a sinus is blocked by obstruction from the tumor.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally reserved for the evaluation of any complications of local sinus infections, particularly suspected intracranial extension. [15] The ability to image in any plane is a considerable advantage in MRI. [17] MRI has a high degree of specificity in differentiating chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (CIFRS) from sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas (SNSCC). [21] On MRI scans, the bony margins of the sinuses are imaged as a plane of absent signal intensity. Moreover, the signal intensity from the high fat content of bone narrow, as in the basisphenoid and petrous apices and around the frontal sinuses, can be confusing, particularly because fluid retained in the sinuses has signal intensity similar to that of the high water content.

Plain radiography is generally obsolete, but exceptions include its use in confirming air-fluid levels in acute sinusitis and in evaluating size and integrity of the paranasal sinuses. Radiographs may still provide a useful adjunct to diagnosis in parts of the world, where sophisticated imaging is not yet available. Whether the Waters view is sufficient for evaluating suspected acute bacterial sinusitis is debated. In general, Waters, Caldwell, and lateral views are obtained. On plain radiographs, other bony structures overlap the sinuses, and the rate of false-negative results is high. The posterior ethmoids are poorly visualized. The ostiomeatal complex cannot be adequately assessed. [22]

(The radiologic characteristics of sinusitis are demonstrated in the images below.)

In general, ultrasonography has not been thought to be useful in the diagnosis of sinusitis. However, several published works have shown it to be more accurate than MRI or plain radiography in the diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis. [23, 24, 25] When used in combination with radiography, sonograms can depict 86% of infections.

Radionuclide studies cannot be regarded as the primary modality in the imaging of sinusitis, but they have a place when cross-sectional imaging cannot differentiate between infection and other causes of mucosal disease. Gallium and labeled white blood cells (WBCs) are nonspecific agents and may be taken up in infections, inflammations, and tumors. Roccatello and associates described facial uptake of indium-111 (111In)-labeled granulocytes in cases of Wegener granulomatosis mimicking sinusitis. [26]

Angiography should be considered if a vascular lesion is suspected. The clinical and imaging findings should be taken into consideration when the surgical approach is planned. [27] Most vascular evaluations can now be performed with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or CT angiography (CTA). However, angiography may still be necessary for planning surgery and radiologic interventions, such as embolization of pseudoaneurysms.

ACR guidelines

The American College of Radiology (ACR) regards noncontrast CT scanning as the examination of choice in recurrent or chronic sinus disease. All imaging findings are interpreted in conjunction with clinical and endoscopic findings. MRI is a complementary study when aggressive disease is being evaluated with ophthalmic/intracranial complications, especially in fungal disease in immunocompromised patients and in characterization of a sinus mass. [28]

The ACR recommendations for sinusitis in children include the following [29] :

-

Imaging studies are not recommended for uncomplicated acute sinusitis:

-

CT of the paranasal sinuses without IV contrast is recommended for persistent sinusitis (worsening course or severe presentation, or not responding to treatment), recurrent sinusitis, or chronic sinusitis, or to define paranasal sinus anatomy before functional endoscopic sinus surgery.

-

CT or MRI of the head and paranasal sinuses with IV contrast is recommended for sinusitis with clinical concern of orbital or intracranial complications. CTA or MR angiography/MR venography may be complementary in cases with suspected vascular complications.

-

CT or MRI of the head and paranasal sinuses with IV contrast is recommended for suspected invasive fungal sinusitis. CTA or MRA/MRV may be complementary in cases with suspected vascular complications.

Anatomy

To evaluate the pattern of sinusitis, one must understand the drainage of various sinuses. The anatomy of drainage revolves around the ostiomeatal unit, which is not a single morphologic structure but a combination of the following structures:

-

Middle turbinate

-

Ethmoid bulla

-

Uncinate process

-

Maxillary infundibulum

-

Hiatus semilunaris (ie, space beneath the middle turbinate)

-

Maxillary os

The hiatus semilunaris is a space between the uncinate process (anteroinferiorly) and the ethmoid bulla (posterosuperiorly). The anterior group of ethmoid air cells drains into the anterior aspect of the hiatus semilunaris through the frontonasal duct. The middle group drains into the hiatus semilunaris on or above the ethmoidal bulla. The frontal sinus drains through the frontonasal duct or through the anterior ethmoidal cells into the hiatus semilunaris.

The maxillary infundibulum drains into the posterior part of the hiatus semilunaris. The frontal, maxillary, anterior, and middle ethmoidal sinuses all drain into the hiatus semilunaris of the middle meatus. Any mechanical block in this region causes inflammation of the above-mentioned sinuses. This is called the ostiomeatal pattern or middle meatus syndrome (see the image below).

Mucosal thickening in the left anterior ethmoid and maxillary sinuses and in the region of the infundibulum. This indicates an ostiomeatal pattern of sinusitis.

Mucosal thickening in the left anterior ethmoid and maxillary sinuses and in the region of the infundibulum. This indicates an ostiomeatal pattern of sinusitis.

The sphenoid sinus drains posterior to the superior turbinate into the sphenoethmoid recess through the sphenoid ostium. The posterior ethmoid air cells also drain through the superior meatus into the sphenoethmoid recess. An obstruction in this region gives rise to the sphenoethmoid pattern of sinusitis.

Normal variants

A concha bullosa (see the image below) is an aerated middle turbinate that can compress the uncinate process and obstruct the middle meatus and the infundibulum. It is present in 35% of the population. The degree of pneumatization may vary from side to side. Usually, 1 cell (and occasionally, 2 or 3 cells) are seen.

The Haller cell, or infraorbital cell, extends inferior to the ethmoid bulla and lateral to the maxillary sinus roof and interposes itself between the lamina papyracea and the uncinate process. A large Haller cell may obstruct the middle meatus. It is usually located in the anterior ethmoid, but it may extend all the way from anterior to posterior. It is seen in 10% of the population, in whom it is unilateral in 5.4% and bilateral in 4.5%.

The middle turbinates may have a paradoxical curve, as shown in the image below, causing narrowing of the middle meatus. A deviated nasal septum or a septal spur may cause compression of the middle turbinates and resultant narrowing of the middle meatus. A large ethmoid bulla can protrude into the middle meatus and cause it to become narrowed.

Content.

Radiography

The Waters view, or occipitomental view, is considered the best projection for evaluating maxillary sinuses, while the Caldwell view, or occipitofrontal view, is used primarily for the frontal and ethmoid sinuses. Sensitivity, however, is relatively low for all sinuses (25-41%) except for maxillary sinusitis (80%). Adjacent bony shadows can overlap the sinuses and make interpretation of radiographs difficult for sinusitis.Examination in the erect position is desirable to reveal fluid levels. [22]

The following projections allow a good assessment of the paranasal sinuses:

-

Waters (occipitomental) view

-

Caldwell (occipitofrontal) view

-

Lateral view

-

Modified basilar view (a submental vertex view)

The Waters view (see the image below) shows the maxillary antra clearly. The frontal sinus is projected obliquely, and the ethmoid air cells are obscured, although a few may be seen along the medial walls of the orbit and within the nose. The sphenoid sinus is seen through the open mouth.

Polypoid mucosal thickening in the right maxillary sinus with a mucous retention cyst in the left on a Waters view.

Polypoid mucosal thickening in the right maxillary sinus with a mucous retention cyst in the left on a Waters view.

In the Caldwell view, the frontal sinuses are well seen. The floors of the maxillary sinuses are visible. The floor of the sella turcica, the crista galli, the nasal septum, and the middle and inferior nasal turbinates can be seen. The anterior ethmoid air cells are also seen. However, the sphenoid sinus is obscured.

In the lateral view, the sphenoid and frontal sinuses are visualized. The rest of the sinuses are superimposed. The nasopharyngeal soft tissue and the adenoids are also well visualized.

A modified basilar view (a submental vertex view) may be a useful adjunct when dealing with sphenoid sinus disease.

An orthopantomographic view is not a standard view and requires different equipment. This provides a panoramic view of the floors of the maxillary sinuses and the upper and lower alveoli.

Fluid levels are the most common finding in acute bacterial sinusitis and are not generally seen in other forms of sinusitis. Mucosal thickening represented by parallel soft-tissue opacity along the bony walls of the sinuses may be seen. Mucous retention cysts are represented by soft-tissue opacity with a surface convex toward the cavity of the sinus, along any of the walls.

Hypertrophy of the turbinates may be seen. The nasal cavities may be filled in with soft tissues; this finding is suggestive of polyps. Total opacification of a sinus may also be seen. If the sinus is more opaque than its pair or the ipsilateral orbit, it is thought to be totally filled in with soft tissues or fluid.

In infants aged 3 years or younger, conventional sinus radiographs usually contribute little, because of sinus opacification that occurs secondary to normal nonpneumatized sinuses. Conventional radiographs allow poor visualization of ethmoid air cells. If used at all, conventional radiographs should be reserved for patients with persistent symptoms despite appropriate therapy. A single occipitomental (Waters view) suffices in this situation.

Degree of confidence

With the advent of CT, the role of conventional radiography has taken second place and has a limited role in the management of sinusitis. There are wide intraobserver differences in the interpretation of plain radiographs, and the rate of false-negative results is high. [30]

Possible findings in acute sinusitis include mucosal thickening, air-fluid levels, and complete opacification of the involved sinus. The role of imaging in acute sinusitis is controversial, and many regard acute sinusitis to be a clinical diagnosis. Mucosal thickening is seen in more than 90% of patients with sinusitis, but this finding is highly nonspecific. Air-fluid levels and complete opacification are more specific for sinusitis, but they are seen in only 60% of sinusitis cases.

Air-fluid levels, as shown in the image below, generally indicate bacterial sinusitis.

Computed Tomography

CT scan evaluation of paranasal sinuses for sinusitis should include an assessment of the pattern, extent, and probable mechanical cause of disease, as well as the relevant anatomic details required for planning surgery. [31]

Lund-Mackay scale for evaluation of images

Various staging systems have been proposed; however, no one system is accepted as the standard for use in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). Many studies use the Lund-Mackay (LM) scale to evaluate radiographic images. This scale grades the right and left sides independently, looking at the maxillary, anterior ethmoids, posterior ethmoids, sphenoid, and frontal sinuses, as well as the ostiomeatal complex. Each sinus is scored a 0 (no abnormality), 1 (partial opacification), or 2 (total opacification), while the ostiomeatal complex is scored either a 0 or 2 (for presence or absence of disease). Scores range from 0-24.

Singh and colleagues analyzed the predictive value of the Lund-Mackay score for FESS outcomes and reported that a minimum LM score of 13.1 correlated with a significant improvement in symptoms and a favorable long-term prognosis. [32]

Pathology

Polypoid mucosal thickening may be seen in the affected sinuses. Polypoid soft-tissue masses may be seen to extend from the sinuses into the nasal cavities. The ostiomeatal complexes may be obstructed by a concha bullosa, an enlarged bulla ethmoidalis, a long infundibulum, or a mucocele. A bony erosion may suggest the presence of a mucocele. An air-fluid level within the sinuses may be seen.

Hyperattenuating soft tissue surrounded by hypoattenuating mucoperiosteum in the sinuses is suggestive of fungal infection, although it can also be seen with inspissated secretions and old polyps. Bony erosion is well demonstrated on CT scans.

The following are the patterns of sinus inflammation on CT scans: (1) polyps; (2) fungal sinusitis; (3) mucocele; (4) sinusitis occurring as sinonasal polyposis or in an infundibular, ostiomeatal unit, sphenoethmoidal recess, or sporadic or unclassifiable pattern; and (5) granulomatous sinusitis, which can be infectious (eg, due to tuberculosis, actinomycosis, rhinoscleroma, or leprosy) or noninfectious (eg, Wegener granulomatosis, sarcoid).

With fungal sinusitis (see the image below), the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses are most commonly involved. Allergic fungal sinusitis can involve complete opacification of multiple paranasal sinuses, unilateral or bilateral; sinus expansion and erosion of a wall of the involved sinus; and high-attenuating areas scattered amid mucosal thickening on nonenhanced scans. These areas are due to inspissated secretions or heavy metals, such as iron, manganese, and calcium. [33, 34]

Fungal sinusitis. Soft tissues occupy the right maxillary and ethmoid sinuses with central hyperattenuating areas typical of fungal sinusitis. Medial walls of the affected sinuses are eroded.

Fungal sinusitis. Soft tissues occupy the right maxillary and ethmoid sinuses with central hyperattenuating areas typical of fungal sinusitis. Medial walls of the affected sinuses are eroded.

Acute, invasive fungal sinusitis can involve aggressive bone erosion with extension of disease into the adjacent soft tissues. Intrasinus high-attenuating areas may not be present in acute, invasive fungal sinusitis. This condition may be associated with orbital, intracranial, and cheek soft-tissue invasion.

Sinus mycetoma may cause a focal area of increased attenuation that is usually centered within a diseased sinus.

Findings of acute sinusitis include an air-fluid level, mucosal thickening, and complete opacification of the sinus. Blood in the sinus due to recent trauma may mimic an air-fluid level in the sinus, but it is easily distinguished by density measurements.

In chronic sinusitis, the ethmoid sinus is commonly involved. Findings include mucosal thickening, complete opacification, bone remodeling and thickening due to osteitis, and polyposis. [10]

Mucoceles often occur in patients with chronic pansinusitis and nasal polyposis. The pathogenesis involves accumulation of mucoid secretions behind an obstructed paranasal sinus ostium, with expansion of the sinus cavity and thinning of the sinus walls. The frontal sinuses account for about 60% of cases; ethmoid sinuses, 30%; and maxillary sinuses, 10%. The sphenoid sinus is only rarely involved. Frontal sinus mucoceles (shown in the image below) may present with decreased visual acuity, visual field defect, proptosis, and intractable headaches.

Frontal mucocele. Expansion of the left frontal sinus indicated by low-attenuating soft tissues with thinning of the walls but no erosion.

Frontal mucocele. Expansion of the left frontal sinus indicated by low-attenuating soft tissues with thinning of the walls but no erosion.

Conventional radiography shows a soft-tissue density mass causing sinus cavity expansion, sometimes with bony erosion. Macroscopic calcification may be seen in 5% of cases, especially where there is superimposed fungal infection. Full assessment requires CT or MRI.

CT scanning techniques and indications

CT techniques include thin-section, high-resolution, and coronal scanning for the evaluation of inflammatory sinonasal disease. Plain coronal scans are typically acquired with 2- to 3-mm sections and a high-frequency algorithm. Scans are obtained from the frontal sinus to the sphenoid sinus. Axial scans are not routinely necessary.

Administration of antibiotics or antihistaminics may be required to permit scanning in patients with minimal symptoms. Having a patient blow his or her nose before scanning is useful for clearing mucus, and a prone position helps to drain fluid away from the ostiomeatal unit.

Correct identification and understanding of acute and chronic frontal sinusitis are important. In a pediatric study of 19 patients with acute frontal sinusitis and 15 with chronic frontal sinusitis, CT scan analysis showed that acute patients had a higher prevalence of complex frontal anatomy (type II cells, concha bullosa). [14]

Complications have been reported in 3% of the cases of frontal sinusitis. Complications of frontal bacterial sinusitis can be severe. In a study of 10 patients (ages 9-70 yr) who underwent CT scans, frontal osteomyelitis was present in 6 cases, extradural empyema in 3, intracranial frontal abscess in 2, and occulo-orbital complications in 3. The main complications that can occur during acute bacterial frontal sinusitis are frontal osteomyelitis; endocranial complications (empyema, abscess, thrombophlebitis, meningitis); oculo-orbital complications; and cellulites infiltrating the soft tissues of the frontal site. CT with contrast is the fundamental tool in the diagnosis of complicated frontal sinusitis. MRI is recommended for suspected endocranial involvement. [15]

Degree of confidence

The preferred imaging modality in the diagnosis of sinusitis is CT, which provides more detailed information about the anatomy and abnormalities of the sinuses than does plain radiography. The ostiomeatal units are brilliantly shown on CT scans, which provide greater definition of the pathology than do other images, especially within the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses. CT also shows the relationship of the sinuses to the orbit and the brain. This is an invaluable piece of information in any patient with rhinosinusitis that is severe enough to produce complications. [35]

The primary role of CT is to aid in the diagnosis and management of recurrent and chronic sinusitis and to define the anatomy of the sinuses prior to surgery.

A nonenhanced, coronal CT viewed in a bone window provides excellent resolution and good definition of the complete ostiomeatal complex and other soft-tissue abnormalities seen in sinusitis. The coronal view is best correlated with findings from sinus surgery. Contrast-enhanced CT may be required in cases of acute sinusitis complicated by periorbital cellulitis or abscess.

False positives/negatives

CT findings should not be interpreted in isolation, and scans should always be read in conjunction with clinical and endoscopic findings because of high rates of false-positive results. Up to 40% of asymptomatic adults have abnormalities on sinus CT scans, as do more than 80% of those with minor upper respiratory tract infections.

In diagnosing sinus fungus balls with CT scanning, a high index of suspicion is necessary and pathologic confirmation is mandatory, according to a study by Dhong et al. The investigators found that the sensitivity of CT evaluation of fungus balls was 62%, and the specificity was 99%. The false-positive and false-negative rates were 22% and 2%, respectively. [36]

In immunocompromised patients with invasive sinusitis, CT findings may be negative in the early stages. In advanced cases, differentiating this condition from malignancy may be difficult on the basis of imaging alone. Thus, the clinician cannot rely solely on CT imaging and must maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating immunocompromised patients to establish a prompt diagnosis. Early nasal endoscopy, along with biopsy and the initiation of appropriate therapy, is necessary to improve the patient's prognosis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Although CT scanning remains the preferred modality for diagnosing sinusitis, MRI is indicated in cases of clinically suspected complications, especially in patients with intracranial complications and an extension of infection or in those with suspected superior sagittal venous thrombosis. Both diagnostic methods have improved the care and outcomes of patients who have sinusitis with complications.

T1-weighted and fat-saturated, T2-weighted coronal sequences are routinely performed. Axial T1- and T2-weighted and fat-saturated, T2-weighted sagittal sequences may also be performed.

Fluid is hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Mucosal swelling may be confused with fluid on T2-weighted MRIs; however, on T1-weighted MRIs, it stands out as soft-tissue thickening against the fluid. Tumor tissue appears hypointense compared to mucosal swelling on T2-weighted images. Mucocele is hyperintense in T1- and T2-weighted sequences because of its protein content. The signal intensity on MR depends on the age and degree of inspissation of the secretions. Older mucoceles will lose their T2 signal and then their T1 signal.

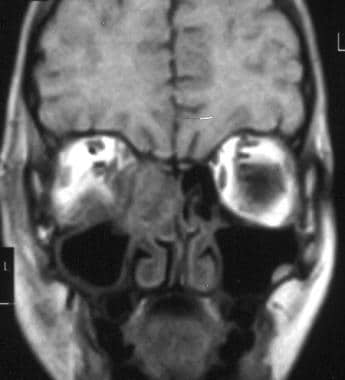

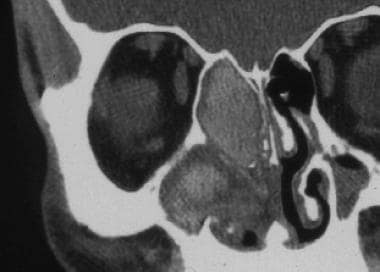

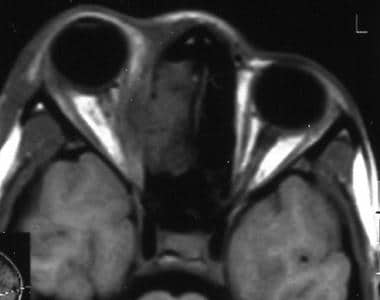

(MRI characteristics of sinusitis are shown in the images below.)

Axial MRI shows right intraorbital extension of sinusitis with medial displacement of medial rectus muscle.

Axial MRI shows right intraorbital extension of sinusitis with medial displacement of medial rectus muscle.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness.

Degree of confidence

MRI improves the differentiation of soft tissue, but it does not help in evaluating bones. MRI clearly depicts tumor from surrounding inflammatory tissue and secretions in the sinuses. CT scanning relies on the high contrast between air, soft tissue, and bone in evaluating the paranasal sinuses. Membrane, polyps, and mucus have similar attenuation, but the polypoid appearance helps distinguish inflammatory polyps. On T2-weighted MRIs, the edematous membrane and mucus are distinctly hyperintense, whereas nasal polyps have more intermediate signal intensity. MRI cannot define bony anatomy as well as CT does.

Other disadvantages of MRI include a high rate of false-positive findings and its higher cost. MRIs take considerably longer to acquire than CT scans, and they may be difficult to obtain in patients who are claustrophobic. The false-positive rate with MRI is high. Abnormal sinus MRI findings are common in otherwise healthy adults, in children attending school, and in totally asymptomatic children. Incidental MRI findings should be interpreted as normal; they do not indicate that children imaged for purposes other than an evaluation of sinus disease require sinus treatment. [37]

Ultrasonography

In general, ultrasonography has not been thought to be useful in the diagnosis of sinusitis. However, several published works have shown it to be more accurate than MRI or plain radiography in the diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis. [23, 24, 25] When used in combination with radiography, sonograms can depict 86% of infections.

A-mode ultrasonography has been a reliable tool in the diagnosis of acute maxillary sinusitis. [38] However, controversy still exists regarding the reliability of A-mode ultrasonography in detecting fluid retention or mucosal swelling in patients with chronic polypous rhinosinusitis or in transantrally operated-on maxillary sinuses.

Ultrasonography has several limitations in the diagnosis of sinusitis. Ultrasonography can result in a positive diagnosis in the presence of antral fluid, but sonograms do not define the cause of the fluid. Sonograms cannot provide information about bony detail, and the diagnosis of frontal, ethmoidal, and sphenoidal sinusitis is difficult.

Ultrasonographic findings cannot be used to differentiate sinus disease from bacterial, viral, fungal, and allergic causes, as with most cross-sectional imaging.

Angiography

Noninflammatory lesions in the sphenoid sinus are common. Therefore, thorough preoperative evaluation is imperative. The location and character of these lesions can be defined by means of nasal endoscopy and CT scanning, and no other investigations may be necessary. In some patients, MRI may help to further define the nature and extent of a lesion.

Angiography should be considered if a vascular lesion is suspected. The clinical and imaging findings should be taken into consideration when the surgical approach is planned. [27] Mycotic aneurysms, cerebral infarction, brain abscess, and intracranial venous thrombosis are rare, but well-known, complications of sinusitis. Sphenoid sinusitis may invade adjacent intracranial vessels, and angiography may be required.

Angiography is an invasive procedure, although it remains the criterion standard for depicting blood-vessel pathology. Most vascular evaluations can now be performed with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or CT angiography (CTA). However, angiography may still be necessary for planning surgery and radiologic interventions, such as embolization of pseudoaneurysms.

Angiography provides little, if any, information regarding sinusitis itself. Although vascular invasion from extension of the sinus inflammatory process or venous thrombosis can be diagnosed reliably with angiography, such pathology has many causes that cannot be differentiated with angiography.

-

Air-fluid level (arrow) in the maxillary sinus suggests sinusitis.

-

Accessory ostia in the medial walls of both maxillary sinuses with left maxillary sinusitis.

-

Deviated nasal septum on a coronal high-resolution CT scan.

-

Bilateral ethmoid sinusitis on an MRI.

-

Concha bullosa of the right middle turbinate.

-

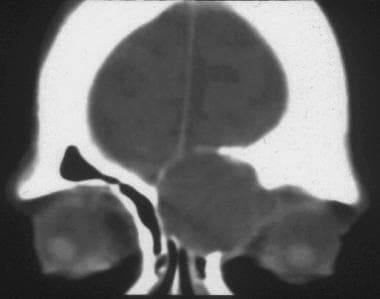

Ethmoid sinusitis with intracranial extension and also extension into the left orbit.

-

Paradoxical curves of both middle turbinates cause narrowing of the ostiomeatal units.

-

Sinonasal polyposis. Soft tissues completely fill the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses and extend into the nasal cavities.

-

CT scan obtained after functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) shows surgical defects in both nasal cavities in the form of excision of the entire right ostiomeatal unit and the left uncinate process with residual left ethmoid and maxillary sinusitis.

-

Polypoid mucosal thickening in the right maxillary sinus with a mucous retention cyst in the left on a Waters view.

-

Right-sided sphenoethmoidal pattern of sinusitis.

-

Mucous retention cysts along the floor of the right and the anterior wall of the left maxillary sinuses.

-

Mucosal thickening in the left anterior ethmoid and maxillary sinuses and in the region of the infundibulum. This indicates an ostiomeatal pattern of sinusitis.

-

Frontal mucocele. Expansion of the left frontal sinus indicated by low-attenuating soft tissues with thinning of the walls but no erosion.

-

Fungal sinusitis. Soft tissues occupy the right maxillary and ethmoid sinuses with central hyperattenuating areas typical of fungal sinusitis. Medial walls of the affected sinuses are eroded.

-

MRI shows intraorbital extension of ethmoid sinusitis on the right side.

-

Axial MRI shows right intraorbital extension of sinusitis with medial displacement of medial rectus muscle.

-

Expansion of the left anterior ethmoid sinuses with thinned, but intact, bony walls; these findings suggest a mucocele.