Practice Essentials

A posterior urethral valve (PUV) is an abnormal congenital obstructing membrane that is located within the posterior male urethra; this valve is the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction in male children. [1, 2, 3] The valve is believed to result from abnormal embryologic development of the fetal posterior urethra. The classic categorization of posterior urethral valves into types I, II, and III was developed by Young et al [4] and has undergone modification over time based on clinical observation and a better understanding of the embryologic events that lead to normal urethral development. [5, 6, 7, 8]

Young's classification is based on the orientation of the valves within the urethra, as follows [5, 6, 7, 8] :

-

Type I (95%): Posterior urethral folds (plicae colliculi) arise from the caudal verumontanum along the lateral margins of the urethra and fuse anteriorly, causing an obstruction.

-

Type II: Membranes cranially attached to the bladder neck originating from the verumontanum. (These are now thought to be caused by hypertrophy of the plicae colliculi and not obstructive valves.)

-

Type III (5%): Round membrane at the caudal verumontanum with a hole in the middle that is either above (type IIIa) the verumontanum or below it (type IIIb). (The holes do no communicates directly with the verumontanum.

Regardless of the type of valve, however, all valves essentially obstruct normal bladder emptying. This anatomic obstruction increases voiding pressures and may alter normal development of the fetal bladder and kidneys. Typically, children with higher degrees of obstruction present earlier with the most severe symptoms. A spectrum of signs and symptoms, ranging from severe obstruction with resultant renal failure and pulmonary hypoplasia leading to neonatal demise to mild obstructive symptoms of voiding dysfunction, may be noted.

Posterior urethral valves account for 17% of pediatric end-stage renal disease. [9, 10]

Imaging modalities

Renal ultrasonography in the male newborn can confirm the antenatal findings of hydroureteronephrosis with a dilated, thick-walled bladder and a dilated posterior urethra. In symptomatic older boys, ultrasonography is useful to screen for these findings of posterior urethral valves. Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to assess the bladder for associated findings of trabeculation, diverticula, and vesicoureteral reflux. [1, 2]

Contrast-enhanced serial voiding urosonography (SVU) has been proposed as a useful complementary test in pediatric patients with PUV. The advantages of SVU include absence of radiation, high sensitivity, and real-time imaging. [11, 12]

VCUG is considered the diagnostic criterion standard imaging modality for posterior urethral valves, but normal mucosal folds (plicae colliculi) may appear as lucencies on VCUG and suggest the presence of valve leaflets. Conversely, valve leaflets may not be visible on VCUG; however, other associated findings with valves should raise suspicions.

VCUG may miss late-presenting cases of PUV. [13] Also, improper VCUG technique can cause the diagnosis to be missed by omission of adequate urethral views during voiding or failure to remove the urinary catheter, which can stent the valves open during voiding. [14]

Findings from renal ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scanning, intravenous pyelography (IVP), and nuclear medicine renal scanning are not diagnostic for posterior urethral valves, although each modality may add details regarding the structure or function of the urinary tract.

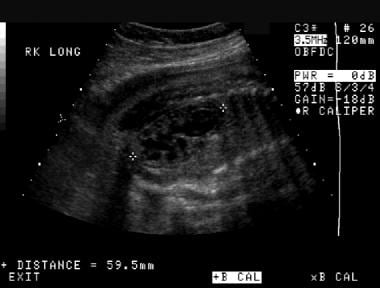

With routine obstetric ultrasonography, the prenatal diagnosis of posterior urethral valve is becoming increasingly common in at least one third of cases, [15] leading to investigative efforts at improving bladder drainage in utero. Postnatal diagnostic modalities and treatment algorithms are fairly well established, and valve management has become less invasive with the development of pediatric endoscopic instruments. Hydronephrosis is demonstrated in the sonograms below. [16]

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. The kidney is larger than expected for the patient's gestational age.

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. The kidney is larger than expected for the patient's gestational age.

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the left kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. As is the case with the right kidney, the left kidney is longer than expected for the patient's gestational age (same patient as in the previous image).

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the left kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. As is the case with the right kidney, the left kidney is longer than expected for the patient's gestational age (same patient as in the previous image).

Pathophysiology

PUV can appear at the earliest stage of urinary tract development; therefore, the entire urinary tract develops in an abnormal environment of high intraluminal pressure due to the anatomic obstruction. Permanent defects in the function of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder may result from prenatal maldevelopment — despite adequate decompression of the urinary tract after birth.

Renal function may be impaired for several reasons. Renal parenchymal dysplasia is common and may be related to maldevelopment of the metanephric blastema (renal precursor tissue) in an environment of high intraluminal pressure. Renal tubular function may be affected by high pressures that result in poor urinary concentrating ability, with resultant obligatory polyuria and the development of ureteral and bladder dysfunction due to high urinary production.

The affected kidneys may function well initially, but they have a reduced renal reserve so that the boy develops renal failure as his body grows. Renal deterioration may also occur due to hyperfiltration injury that causes glomerulosclerosis, chronic pyelonephritis associated with vesicoureteral reflux, urinary stasis, or incomplete bladder emptying, all of which are common in boys with PUV and can cause further insult to the developing kidneys.

Hydronephrosis is common and may be due to a variety of causes. First, bladder dysfunction with high back pressures on the ureter may be causative. Second, the ureter itself may develop an abnormally deficient musculature due to chronic distention from high pressure or high urine flow. Third, high urinary flow due to the lack of urinary concentrating ability of the nephron can dilate the kidneys and ureters. Finally, there may be abnormalities of the vesicoureteral junction, such as reflux or, rarely, ureterovesical obstruction.

Vesicoureteral reflux is present in one half of male patients with a posterior urethral valve and is often thought to be physiologic, secondary to high bladder pressures overcoming the competence of the ureterovesical junction. Reflux may also be anatomic, secondary to abnormal ureteral orifice position resulting from abnormal ureteral bud development during embryogenesis.

Irreversible bladder dysfunction may occur due to alterations in collagen deposition in addition to the development of hypertrophy of detrusor smooth muscle cells. Several authors have noted high pressure due to poor compliance or uninhibited contraction of the detrusor muscle and eventual myogenic failure. In mild cases, incontinence may be present; in severe cases, ongoing deterioration of renal function occurs due to high detrusor pressure with incomplete emptying and, possibly, vesicoureteral reflux.

Bladder dysfunction often improves over time after definitive treatment of the obstruction. [17] Management of the persistently hostile bladder is imperative to diminish further renal impairment and the risk of urinary tract infection (UTI), persistent hydronephrosis or vesicoureteral reflux, and incontinence.

Several protective mechanisms may develop in boys with a posterior urethral valve; these may lower intraluminal pressures and allow at least one renal unit to develop more normally. These mechanisms include massive unilateral vesicoureteral reflux (usually associated with an ipsilateral dysplastic kidney, known as vesicoureteral reflux and dysplasia [VURD] syndrome), bladder diverticula, and urinary ascites.

The final goal of all therapeutic intervention for posterior urethral valve is proper urinary tract function, with protection of the renal units. As a result of progress in the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of this condition, morbidity and mortality rates have markedly diminished over the past several decades. However, PUV remains a common cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD). In a cohort study of 173 patients with PUVs, 37.6% developed stage 3 or higher CKD. The study found that baseline creatinine, nadir creatinine, and proteinuria were predictors of CKD. [18]

Radiography

Plain radiographs do not add to the actual diagnosis of PUV; however, chest radiography may be useful in the evaluation of pulmonary hypoplasia, and images of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (KUB images) may show the ground-glass appearance of urinary ascites, if present.

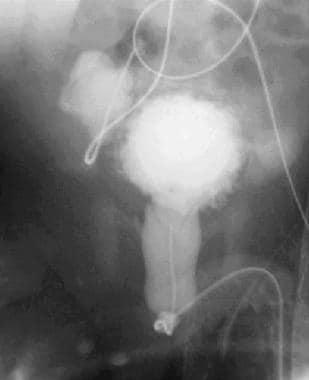

VCUG (represented in the images below) is considered the diagnostic study of choice for the evaluation of posterior urethral valves. [1] The bladder is typically thickened with trabeculae and may exhibit vesicoureteral reflux or, less commonly, diverticula. The bladder neck is typically hypertrophic, leading to a lucent ring or collar. The constellation of bladder and urethral abnormalities with or without valve identification typically confirms the presence of PUV. Cystourethroscopy with the patient under general anesthesia may be required to formally confirm the presence of PUV at the time of intervention.

Anteroposterior view of the abdomen during a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates a dilated bladder with trabeculation, diverticula, and bilateral massive reflux.

Anteroposterior view of the abdomen during a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates a dilated bladder with trabeculation, diverticula, and bilateral massive reflux.

Anteroposterior view of the abdomen during a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates bilateral grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux. No intrarenal reflux is noted.

Anteroposterior view of the abdomen during a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates bilateral grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux. No intrarenal reflux is noted.

Sagittal voiding image of the bladder and urethra that was obtained from a voiding cystourethrographic study before catheter removal. This image demonstrates a trabeculated, hypertrophied bladder. The bladder neck is hypertrophied and well demarcated between the body of the bladder and the dilated posterior urethra, the latter of which has the classic spinnaker-sail appearance.

Sagittal voiding image of the bladder and urethra that was obtained from a voiding cystourethrographic study before catheter removal. This image demonstrates a trabeculated, hypertrophied bladder. The bladder neck is hypertrophied and well demarcated between the body of the bladder and the dilated posterior urethra, the latter of which has the classic spinnaker-sail appearance.

Late anteroposterior image from a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates a small, trabeculated bladder with bilateral diverticula. The posterior urethra is dilated.

Late anteroposterior image from a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates a small, trabeculated bladder with bilateral diverticula. The posterior urethra is dilated.

Lateral view of a voiding cystourethrographic study during voiding after catheter removal. The dilated posterior urethra is highly suggestive of a posterior urethral valve, which is seen as the nonopacified line that separates the dilated posterior urethra from the normal-caliber distal urethra. The absence of the urethral catheter may be critical to demonstrate the valve, as good urethral distension is mandatory.

Lateral view of a voiding cystourethrographic study during voiding after catheter removal. The dilated posterior urethra is highly suggestive of a posterior urethral valve, which is seen as the nonopacified line that separates the dilated posterior urethra from the normal-caliber distal urethra. The absence of the urethral catheter may be critical to demonstrate the valve, as good urethral distension is mandatory.

On voiding, the posterior urethra is dilated (ie, rectangular or shield shaped), and valve leaflets may be seen as lucencies, sometimes giving the appearance of a spinning top. If leaflets are not visible, a commonly associated finding of posterior urethral bulging distally over the bulbar urethra may be noted. The anterior urethra is typically underfilled, and voiding is incomplete.

IVP is not routinely used in children, because the contrast agent is poorly concentrated and visualized in newborn kidneys, particularly if renal function is diminished. Elevated serum creatinine levels may preclude the use of IV contrast material. IVP can show an absent kidney in the case of renal dysplasia or delayed renal function with persistent high intraluminal pressures. Hydroureteronephrosis may be seen. Delayed images may show bladder or urethral pathology, but the lower urinary tract is better visualized with VCUG.

False positives/negatives

Regarding false-positive findings, any of the obstructive etiologies may show bladder and upper-tract changes that are typical of posterior urethral valves. However, most of the listed conditions have significant differences in imaging that separate them from posterior valves, such as the location of involvement (anterior valves, syringocele), associated anomalies (prune belly syndrome), and degree of impairment (plicae colliculi). False-positive results should not be seen with functional disorders, because the posterior urethra should not be dilated, except potentially in detrusor sphincter dyssynergy/dyssynergia.

False-negative results are rarely noted in cases of posterior urethral valve that have minimal anatomic obstruction and, thus, limited functional impairment and upper-tract changes. In boys with these findings, VCUG may not show valve leaflets, and cystoscopy may be required based on symptoms. [19]

However, in a boy with the clinical stigmata of a posterior valve in whom definitive visualization of the valve is lacking, cystourethroscopy may be indicated to rule out urethral pathology. It is important to obtain voiding images in the lateral view with—and, ideally, without—the catheter in situ, because the images with the catheter removed optimally demonstrate the valves. It has long been believed that leaving the urethral catheter in place may hold the valves open and prevent proper visualization, but that does not happen in practice if good urethral distention is achieved.

In the postoperative setting after valve ablation, some posterior urethral dilatation usually persists, with secondary bladder changes. However, if incomplete valve ablation is suspected, then repeating cystourethroscopy rather than VCUG is recommended.

Computed Tomography

Rarely necessary in neonates, CT scans with IV contrast enhancement may reveal dysplastic and/or dilated kidneys with delayed renal function and excretion, hydroureter, dilated bladder with wall thickening, trabeculation, and diverticula. A dilated posterior urethra might be seen, although leaflets may be easily missed. Elevated serum creatinine levels generally preclude use of IV contrast material.

CT scans cannot reliably depict valves, although they should reveal the sequelae of bladder outlet obstruction.

False findings are identical to those for radiography. An exception is that plicae colliculi, which might be seen on VCUG studies, should not be noted on CT scans.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings are similar to those of CT scanning except that enhancement with IV gadolinium-based contrast agents may allow functional, as well as anatomic, assessment.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness. [20]

The degree of confidence is similar to that with CT scanning. False findings are similar to those observed with CT scanning.

Ultrasonography

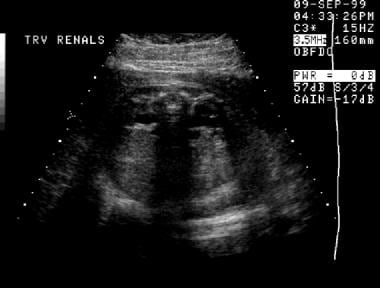

Early ultrasonography after birth is critical to the workup of prenatally detected cases to confirm prenatal findings. In older boys with symptoms of persistent voiding dysfunction or recurrent UTIs, ultrasonography is typically the first step in urinary tract imaging. A proper ultrasonographic study to evaluate the urinary tract must include images of both kidneys, the ureters, and the bladder. Hydroureteronephrosis, with or without cortical thinning, along with a thick-walled bladder with trabeculation and diverticula and a dilated posterior urethra with a hypertrophic bladder neck, are usually seen.

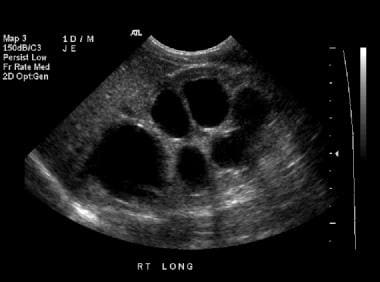

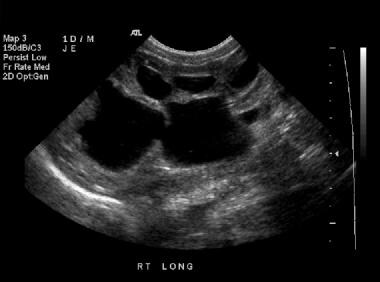

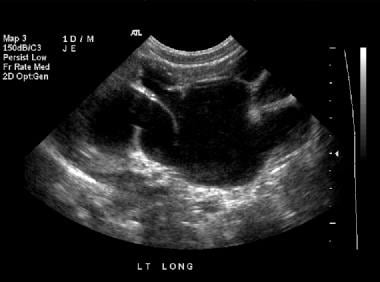

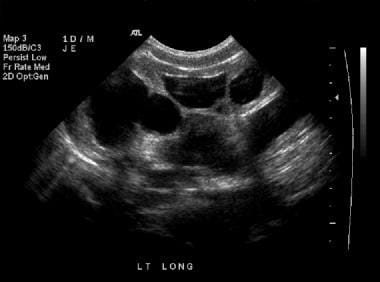

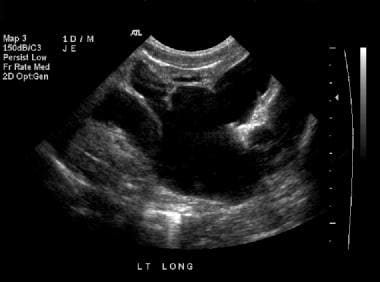

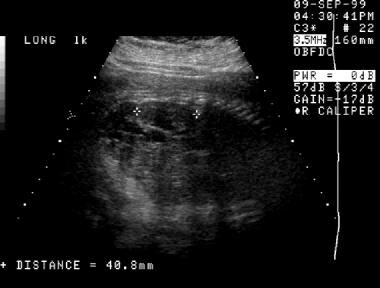

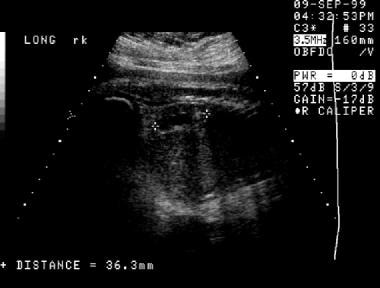

(The ultrasonographic characteristics of hydronephrosis and possible renal cortical thinning are seen in the images below.)

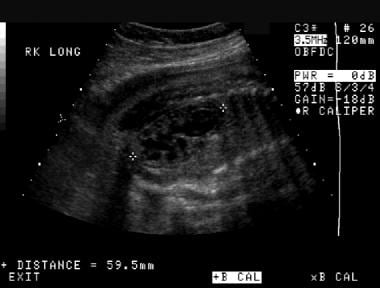

Longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney in a 1-day-old male infant. This image demonstrates grade 4 hydronephrosis, with thinning of the renal parenchyma.

Longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney in a 1-day-old male infant. This image demonstrates grade 4 hydronephrosis, with thinning of the renal parenchyma.

Longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows that the hypoechoic areas interconnect, a finding that is consistent with hydronephrosis rather than multiple distinct renal cysts, which do not interconnect.

Longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows that the hypoechoic areas interconnect, a finding that is consistent with hydronephrosis rather than multiple distinct renal cysts, which do not interconnect.

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 2 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 2 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 3 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 3 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 4 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 4 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. The kidney is larger than expected for the patient's gestational age.

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. The kidney is larger than expected for the patient's gestational age.

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the left kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. As is the case with the right kidney, the left kidney is longer than expected for the patient's gestational age (same patient as in the previous image).

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the left kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. As is the case with the right kidney, the left kidney is longer than expected for the patient's gestational age (same patient as in the previous image).

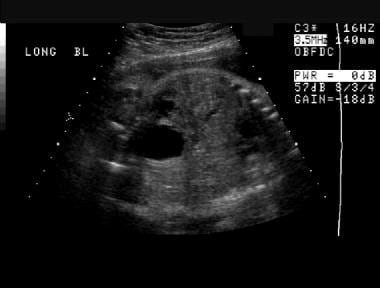

In the setting of renal dysplasia, the renal parenchyma is typically hyperechogenic with visible small cysts (< 10 mm), but in the most mildly affected cases, renal ultrasonographic findings may be normal. Echogenic lines that are the actual valve leaflets might be seen. The combination of the dilated, thick-walled bladder and dilated posterior urethra has been described as having a keyhole appearance (as demonstrated in the image below).

Longitudinal sonogram of the bladder. This image demonstrates a distended bladder, with the classic keyhole appearance of the posterior urethra seen distally (on the right).

Longitudinal sonogram of the bladder. This image demonstrates a distended bladder, with the classic keyhole appearance of the posterior urethra seen distally (on the right).

The bladder may be of large or small volume, but it is invariably thick-walled. Urinary ascites or perinephric collections due to urinomas may also be seen, most commonly soon after birth, and are caused by rupture of the urinary tract, typically at the level of the calyces. A suggestive prenatal sonogram reveals a male fetus with bilateral hydroureteronephrosis; a dilated and thickened bladder with poor emptying; and, possibly, oligohydramnios (features seen in the images below). After the diagnosis has been established and initial management has begun, ultrasonography is useful to follow up on the degree of hydronephrosis and parenchymal integrity after treatment, as well as the adequacy of bladder evacuation with voiding (or initial catheter placement prior to definitive surgical management) and the resolution of any urinomas.

Prenatal axial sonogram of the abdomen. This image demonstrates bilateral hydronephrosis. (The spine is the echogenic ring near the top of the image.)

Prenatal axial sonogram of the abdomen. This image demonstrates bilateral hydronephrosis. (The spine is the echogenic ring near the top of the image.)

Prenatal sonogram almost in the coronal plane. A distended urinary bladder is depicted throughout this image as well as previous prenatal ultrasonographic studies. The bladder wall may be thickened.

Prenatal sonogram almost in the coronal plane. A distended urinary bladder is depicted throughout this image as well as previous prenatal ultrasonographic studies. The bladder wall may be thickened.

Prenatal sonogram almost in the coronal plane (same patient as in the previous image). A distended urinary bladder is depicted throughout this image as well as previous prenatal ultrasonographic studies. The bladder wall may be thickened.

Prenatal sonogram almost in the coronal plane (same patient as in the previous image). A distended urinary bladder is depicted throughout this image as well as previous prenatal ultrasonographic studies. The bladder wall may be thickened.

An initial prenatal sonogram. This image demonstrates a distended urinary bladder and oligohydramnios.

An initial prenatal sonogram. This image demonstrates a distended urinary bladder and oligohydramnios.

A first prenatal sonogram. This image demonstrates a cystic area in the region of the left renal fossa. This cystic area appears to be separate from the left kidney, which is located just to the left of the fluid collection on the image. The fluid collection was thought to represent a urinoma.

A first prenatal sonogram. This image demonstrates a cystic area in the region of the left renal fossa. This cystic area appears to be separate from the left kidney, which is located just to the left of the fluid collection on the image. The fluid collection was thought to represent a urinoma.

A second prenatal sonogram (same patient as in the previous image). This image demonstrates interval resolution of the fluid collection in the left renal fossa and a left kidney with hydronephrosis.

A second prenatal sonogram (same patient as in the previous image). This image demonstrates interval resolution of the fluid collection in the left renal fossa and a left kidney with hydronephrosis.

A second prenatal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 2 images). This image also demonstrates hydronephrosis that involves the right kidney.

A second prenatal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 2 images). This image also demonstrates hydronephrosis that involves the right kidney.

A second prenatal sonogram, transverse view (same patient as in the previous 3 images). This image of the abdomen demonstrates bilateral hydronephrosis.

A second prenatal sonogram, transverse view (same patient as in the previous 3 images). This image of the abdomen demonstrates bilateral hydronephrosis.

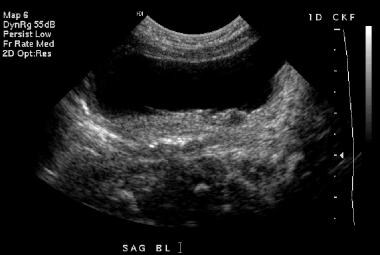

Postnatal sonogram on the first day of life (same patient as in the previous 4 images). This sagittal image of the bladder demonstrates bladder wall thickening and prominence of the distal left ureter.

Postnatal sonogram on the first day of life (same patient as in the previous 4 images). This sagittal image of the bladder demonstrates bladder wall thickening and prominence of the distal left ureter.

Transverse sonogram of the bladder (same patient as in the previous 5 images). Bladder wall thickening is again demonstrated.

Transverse sonogram of the bladder (same patient as in the previous 5 images). Bladder wall thickening is again demonstrated.

Degree of confidence

The sum of the ultrasonographic findings with clinical correlates, combined with the rarity of other obstructive lesions, is highly indicative of PUV. The valves typically cannot be seen on sonograms, and VCUG is required to make the definitive diagnosis.

False-positive results may be seen with other obstructive and functional disorders of bladder emptying. The ultrasonographic findings are the final common signs of most of the conditions in the differential diagnosis. False-negative results may be seen in mild cases without upper-tract abnormality and an essentially normal bladder.

In a study by Williams et al, the reported sensitivity of renal and bladder ultrasonography for valves was 87% in patients younger than 4 years and 98% for those age 4 years or older. [21]

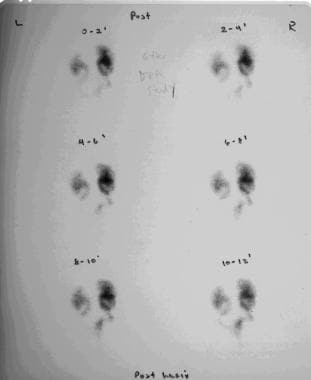

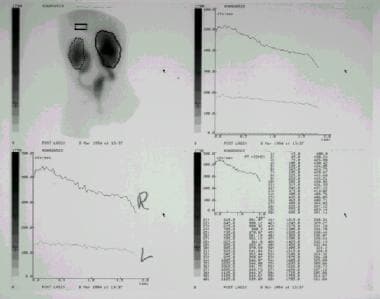

Nuclear Imaging

Nuclear cystography has no role in the diagnosis of posterior urethral valves because of the poor anatomic detail, but this modality can depict the presence of vesicoureteral reflux. Although nuclear medicine study is poor for the specific diagnosis of PUV, it is excellent for assessment of the upper-tract consequences. However, grading of such reflux is not as accurate as with contrast VCUG.

Nuclear renography may be used to assess upper-tract consequences of bladder outlet obstruction. A urethral catheter must be placed before the study to eliminate the effect of a distended, high-pressure bladder on renal function and drainage. An absent or dysplastic kidney is seen as a photopenic area in the renal fossa.

Delayed visualization of a renal unit with a slow rise to peak activity suggests altered renal function. Differential renal function is important to estimate relative renal impairment and is based on activity at 1-2 minutes after injection of a tracer. Hydronephrosis with ureteral dilatation can represent ureterovesical obstruction or chronic nonobstructive changes of posterior urethral valves; the latter should demonstrate washout after furosemide administration, if renal function is adequate.

False-positive findings can result when a urethral catheter is not used. High bladder storage pressure or vesicoureteral reflux can prevent drainage from the kidney and ureter. Distal ureteral obstruction by ureterovesical junction obstruction or a ureterocele can mimic the changes of valves. False-negative findings can be seen in cases in which there is normal renal function and drainage.

(Renal scan images are shown below.)

Excretory images obtained from renal scanning that was performed with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. This study demonstrates radiotracer accumulation within the dilated renal collecting systems and dilated ureters. The bladder remains empty because of catheter drainage.

Excretory images obtained from renal scanning that was performed with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. This study demonstrates radiotracer accumulation within the dilated renal collecting systems and dilated ureters. The bladder remains empty because of catheter drainage.

Renal scanning images performed with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. This study demonstrates accumulation of radiotracer within the renal collecting systems bilaterally, within the dilated ureters bilaterally, and within a small, irregular-appearing bladder. Renograms (top right and bottom left) demonstrate poor clearance of contrast material from the renal collecting systems. The relatively poorer function in the left kidney reflects congenital renal dysplasia.

Renal scanning images performed with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. This study demonstrates accumulation of radiotracer within the renal collecting systems bilaterally, within the dilated ureters bilaterally, and within a small, irregular-appearing bladder. Renograms (top right and bottom left) demonstrate poor clearance of contrast material from the renal collecting systems. The relatively poorer function in the left kidney reflects congenital renal dysplasia.

-

Anteroposterior view of the abdomen during a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates a dilated bladder with trabeculation, diverticula, and bilateral massive reflux.

-

Anteroposterior view of the abdomen during a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates bilateral grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux. No intrarenal reflux is noted.

-

Sagittal voiding image of the bladder and urethra that was obtained from a voiding cystourethrographic study before catheter removal. This image demonstrates a trabeculated, hypertrophied bladder. The bladder neck is hypertrophied and well demarcated between the body of the bladder and the dilated posterior urethra, the latter of which has the classic spinnaker-sail appearance.

-

Late anteroposterior image from a voiding cystourethrographic study. This image demonstrates a small, trabeculated bladder with bilateral diverticula. The posterior urethra is dilated.

-

Lateral view of a voiding cystourethrographic study during voiding after catheter removal. The dilated posterior urethra is highly suggestive of a posterior urethral valve, which is seen as the nonopacified line that separates the dilated posterior urethra from the normal-caliber distal urethra. The absence of the urethral catheter may be critical to demonstrate the valve, as good urethral distension is mandatory.

-

Longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney in a 1-day-old male infant. This image demonstrates grade 4 hydronephrosis, with thinning of the renal parenchyma.

-

Longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows that the hypoechoic areas interconnect, a finding that is consistent with hydronephrosis rather than multiple distinct renal cysts, which do not interconnect.

-

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 2 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

-

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 3 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

-

Renal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 4 images). This image shows grade 4 hydronephrosis of the left kidney.

-

Longitudinal sonogram of the bladder. This image demonstrates a distended bladder, with the classic keyhole appearance of the posterior urethra seen distally (on the right).

-

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the right kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. The kidney is larger than expected for the patient's gestational age.

-

Prenatal longitudinal sonogram of the left kidney. This image demonstrates significant hydronephrosis with possible renal cortical thinning. As is the case with the right kidney, the left kidney is longer than expected for the patient's gestational age (same patient as in the previous image).

-

Prenatal axial sonogram of the abdomen. This image demonstrates bilateral hydronephrosis. (The spine is the echogenic ring near the top of the image.)

-

Prenatal sonogram almost in the coronal plane. A distended urinary bladder is depicted throughout this image as well as previous prenatal ultrasonographic studies. The bladder wall may be thickened.

-

Prenatal sonogram almost in the coronal plane (same patient as in the previous image). A distended urinary bladder is depicted throughout this image as well as previous prenatal ultrasonographic studies. The bladder wall may be thickened.

-

An initial prenatal sonogram. This image demonstrates a distended urinary bladder and oligohydramnios.

-

A first prenatal sonogram. This image demonstrates a cystic area in the region of the left renal fossa. This cystic area appears to be separate from the left kidney, which is located just to the left of the fluid collection on the image. The fluid collection was thought to represent a urinoma.

-

This sonogram demonstrates mild hydronephrosis that involves the right kidney.

-

A second prenatal sonogram (same patient as in the previous image). This image demonstrates interval resolution of the fluid collection in the left renal fossa and a left kidney with hydronephrosis.

-

A second prenatal sonogram (same patient as in the previous 2 images). This image also demonstrates hydronephrosis that involves the right kidney.

-

A second prenatal sonogram, transverse view (same patient as in the previous 3 images). This image of the abdomen demonstrates bilateral hydronephrosis.

-

Postnatal sonogram on the first day of life (same patient as in the previous 4 images). This sagittal image of the bladder demonstrates bladder wall thickening and prominence of the distal left ureter.

-

Transverse sonogram of the bladder (same patient as in the previous 5 images). Bladder wall thickening is again demonstrated.

-

Excretory images obtained from renal scanning that was performed with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. This study demonstrates radiotracer accumulation within the dilated renal collecting systems and dilated ureters. The bladder remains empty because of catheter drainage.

-

Renal scanning images performed with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. This study demonstrates accumulation of radiotracer within the renal collecting systems bilaterally, within the dilated ureters bilaterally, and within a small, irregular-appearing bladder. Renograms (top right and bottom left) demonstrate poor clearance of contrast material from the renal collecting systems. The relatively poorer function in the left kidney reflects congenital renal dysplasia.