Practice Essentials

Extensive calcium encrustation of the gallbladder wall has been variably termed calcified gallbladder, calcifying cholecystitis, or cholecystopathia chronica calcarea. The term "porcelain gallbladder" has been used to emphasize the blue discoloration and brittle consistency of the gallbladder wall at surgery. Some authorities eschew these terms and instead call all calcified gallbladders "porcelain gallbladders."The true incidence of porcelain gallbladder is unknown, but it is reported to be 0.6-0.8%, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:5. Most porcelain gallbladders (90-95%) are associated with gallstone. Mean age at diagnosis is 32 to 70 years. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Patients with porcelain gallbladder are usually asymptomatic, and the condition is usually found incidentally on plain abdominal radiographs, sonograms, or computed tomography (CT) images. [10, 11, 12, 13]

Porcelain gallbladder is an uncommon condition; recognizing the clinical and imaging characteristics of the disease is important because of the high frequency (22%) of adenocarcinoma in porcelain gallbladder. [14] Nonetheless, the causal relationship between porcelain gallbladder and malignancy has not been established. Studies have shown that porcelain gallbladder has a weaker association with gallbladder carcinoma than once thought. [3, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17]

Radiologic intervention is possible when an associated adenocarcinoma exists; the tumor can cause bile duct obstruction as a result of direct invasion or obstruction of the ducts as a consequence of lymph node metastases. [18] The goal of intervention is to maintain biliary patency by means of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or external and/or internal biliary drainage by using percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. [19] The spontaneous resolution of porcelain gallbladder has not been described; however, spontaneous resolution is a rare occurrence in milky bile syndrome. [20]

Preferred examination

Although most porcelain gallbladders are incidentally seen on plain abdominal radiographs, the definition and sensitivity provided by CT scanning appears to be far superior to the definition and sensitivity of radiography. CT is also superior to radiography for staging gallbladder carcinoma when it is a complication of porcelain gallbladder. [21, 22, 5]

Sonograms do not depict porcelain gallbladder as well as CT scans do; sonographic findings can mimic those seen with a nonfunctioning gallbladder, large calculus, and emphysematous cholecystitis. (Patients with emphysematous cholecystitis usually have diabetes with no point tenderness [ie, diabetic neuropathy]. In one third of these patients, the white blood cell [WBC] count is within the normal range. High-level echoes that outline the gallbladder result from gas within the gallbladder wall. With emphysematous cholecystitis, the male-to-female ratio is 5:1.) [16, 23]

Occasionally, hepatobiliary surgeons may order angiograms when a malignant change has occurred and staging is required.

Radionuclide uptake images obtained with technetium-99m hepatoiminodiacetic acid (HIDA) demonstrate a nonfunctioning gallbladder. Porcelain gallbladder has been detected on bone scans. [24] Nuclear medicine findings are nonspecific because HIDA uptake shows nonfunction in acute cholecystitis and chronic cholecystitis. HIDA uptake scanning is not a recommended imaging procedure for the assessment of porcelain gallbladder.

(See the image below.)

A plain abdominal radiograph that shows a right upper quadrant pyriform opaque mass with curvilinear calcification; this finding suggests porcelain gallbladder.

A plain abdominal radiograph that shows a right upper quadrant pyriform opaque mass with curvilinear calcification; this finding suggests porcelain gallbladder.

Calcification in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen has several causes. Calcification can be categorized by the organ system in which it appears; for example, calcification can affect the liver, gallbladder, right kidney, digestive tract, peritoneal cavity, right adrenal gland, and retroperitoneum.

Diseases associated with these organs include large gallbladder opaque calculi, milk-of-calcium bile (see first image below), echinococcal cysts (see second and third images below), schistosomiasis and other granulomatous diseases, [25] old liver infarcts that have healed (see fourth image below), calcified renal cysts, renal calculi, calcified nonparasitic liver cysts, primary and metastatic liver tumors, benign liver tumors, and calcification in old adrenal hemorrhage and adrenal masses.

This plain abdominal radiograph shows milk-of-calcium bile and a calculus that obstructs the Hartmann pouch.

This plain abdominal radiograph shows milk-of-calcium bile and a calculus that obstructs the Hartmann pouch.

A plain radiograph of the right upper quadrant that shows curvilinear calcification in 2 hydatid cysts in a patient from a region in which hydatid disease is endemic.

A plain radiograph of the right upper quadrant that shows curvilinear calcification in 2 hydatid cysts in a patient from a region in which hydatid disease is endemic.

This transaxial CT scan of the liver shows a calcified hydatid cyst, which can mimic porcelain gallbladder.

This transaxial CT scan of the liver shows a calcified hydatid cyst, which can mimic porcelain gallbladder.

A plain abdominal radiograph of the right upper quadrant of a patient with a history of a hepatic injury that occurred 10 years ago shows curvilinear calcification in 2 mass lesions in the right lobe of the liver.

A plain abdominal radiograph of the right upper quadrant of a patient with a history of a hepatic injury that occurred 10 years ago shows curvilinear calcification in 2 mass lesions in the right lobe of the liver.

Detecting gallbladder cancer in early the stages offers patients their best chance of cure. Many predisposing factors of developing gallbladder cancer exist, including new molecular perspectives on cholesterol cycling, hormonal factors, bacterial infections, and other risk factors for gallstones. Female sex and geographic location are other known factors. The significance of polyps in predisposing to gallbladder cancer is probably overestimated. Sub-centimeter gallbladder polyps rarely become cancerous. Because gallbladder wall thickening is often the first sign of malignancy, all gallbladder imaging should be scrutinized carefully for this sign. [15]

Gupta and Misra have described a rare presentation of porcelain gallbladder with extensive dense transmural biconvex curvilinear calcification of gallbladder and dense central intrahepatic ductal calcification with peripheral ductal dilatation on contrast enhanced CT scans. [26]

Limitations of techniques

In porcelain gallbladder, plain radiographic findings are usually straightforward and are not often confused with findings related to other causes of calcification in the right upper quadrant. If doubt exists, cross-sectional imaging with a modality such as ultrasonography or CT can more accurately depict calcification in the appropriate organ. [27]

Porcelain gallbladder must be distinguished from large solitary calcified gallstones, which are seldom as large as porcelain gallbladders; however, exceptions can complicate a definite diagnosis. Milky bile syndrome is characterized by radiopaque material that causes sufficient opacification of the gallbladder to cause it to be depicted on plain abdominal radiographs. Calculi in the cystic duct and/or Hartmann pouch usually obstruct the gallbladder, and the gallbladder wall will appear inflamed.

The spontaneous expulsion of limy bile along with gallbladder calculi has been reported. The puttylike radiopaque material consists of calcium carbonate or, less commonly, calcium phosphate or calcium bilirubinate. The appearance of limy bile syndrome may simulate that of the gallbladder after the oral or intravenous administration of contrast medium; differentiation between limy bile syndrome and the gallbladder requires knowing whether cholecystographic contrast medium has been administered to the patient. [28, 29]

Calcification of the gallbladder wall or milk-of-calcium bile may have identical appearances on sonograms; therefore, plain radiography is important in distinguishing these entities. Calcified hydatid cysts in the liver are fairly common in endemic areas, such as the Middle East, Eastern and Mediterranean Europe, and North Africa. These cysts can mimic porcelain gallbladder on plain abdominal radiographs; however, the patient's country of origin or history of travel to endemic regions suggests the diagnosis of calcified hydatid cysts.

Ultrasonography will reveal the true gallbladder. [30] Fataar et al described calcified gallbladder granulomas in schistosomal infestation that are dense enough to be seen on abdominal radiographs. [25]

Serpiginous calcification, as seen on plain radiographs of the abdomen in the region of the gallbladder neck, appears to indicate gallbladder schistosomiasis in patients from endemic areas. [25] Calcifications in nonparasitic hepatic and renal cysts, in the adrenal gland, and in liver tumors usually are dissimilar to those in porcelain gallbladder. If confusion remains, sonograms or CT scans can be used to clarify the issue.

Emphysematous cholecystitis can mimic porcelain gallbladder on sonograms; however, their clinical presentation is distinct from that of porcelain gallbladder. Ring-down shadows from gas within the gallbladder wall or lumen may be evident, and plain radiographs may show gas within the gallbladder fossa.

Radiography

Plain abdominal radiographs may demonstrate curvilinear calcification in the right hypochondrium, which corresponds to the location and shape of the gallbladder (see image below). The thickness of the calcification is variable; it may be thin and faintly visible or amorphous, patchy, and thick. The gallbladder may be large, but its size can vary considerably. Oral cholecystography reveals a nonfunctioning gallbladder.

A plain abdominal radiograph that shows a right upper quadrant pyriform opaque mass with curvilinear calcification; this finding suggests porcelain gallbladder.

A plain abdominal radiograph that shows a right upper quadrant pyriform opaque mass with curvilinear calcification; this finding suggests porcelain gallbladder.

Although plain abdominal radiographs have been a standard technique for demonstrating right upper quadrant calcification, sonograms and CT scans appear to be more sensitive (see image below). In some patients, plain abdominal radiographs may show no abnormalities. It is no longer considered adequate to use only plain radiographs when evaluating possible calcifications in the upper abdomen. [27]

This CT scan obtained in a patient with nonbiliary symptoms shows a partial gallbladder wall calcification that suggests porcelain gallbladder.

This CT scan obtained in a patient with nonbiliary symptoms shows a partial gallbladder wall calcification that suggests porcelain gallbladder.

Calcification in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen has several causes. Calcification can be categorized by the organ system in which it appears; for example, calcification can affect the liver, gallbladder, right kidney, digestive tract, peritoneal cavity, right adrenal gland, and retroperitoneum. Diseases that are associated with these organs include large gallbladder opaque calculi, milk-of-calcium bile, echinococcal cysts, schistosomiasis and other granulomatous disease, old liver infarcts that have healed, calcified renal cysts, renal calculi, calcified nonparasitic liver cysts, primary and metastatic liver tumors, benign liver tumors, and calcification in old adrenal hemorrhage and adrenal masses.

In porcelain gallbladder, plain radiographic findings are usually straightforward and are not often confused with findings related to other causes of calcification in the right upper quadrant. Calcified gallbladder granulomas in schistosomal infestation that are dense enough to be seen on abdominal radiographs have been described. Serpiginous calcification on plain abdominal radiographs in the region of the neck of the gallbladder appears to indicate gallbladder schistosomiasis in patients from endemic areas. [25]

Computed Tomography

Although plain abdominal radiographs have been the standard technique for demonstrating right upper quadrant calcification, CT scans appear to be more sensitive than radiographs. In some patients, plain abdominal radiographs may show no abnormalities. It is no longer considered adequate to use only plain radiographs when evaluating possible calcifications in the upper abdomen. [27] CT scans of porcelain gallbladder will show a curvilinear or rim calcification, which is usually associated with calculi in the anatomic location of the gallbladder. With gallbladder carcinoma (see images below), an associated pericholecystic mass may be visualized and intrahepatic metastases and hilar lymphadenopathy may be evident.

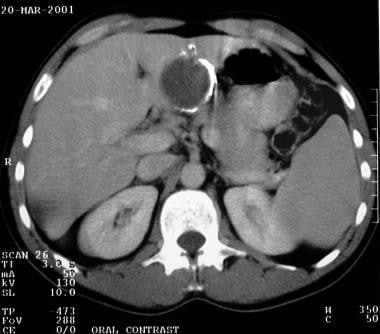

A transaxial enhanced CT scan of a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed.

A transaxial enhanced CT scan of a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed.

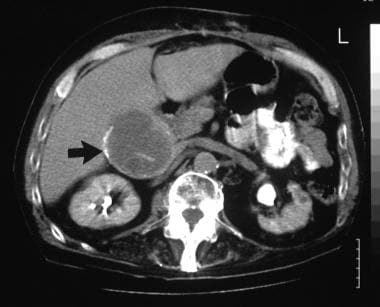

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder, which is associated with a gallbladder calculus (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder, which is associated with a gallbladder calculus (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

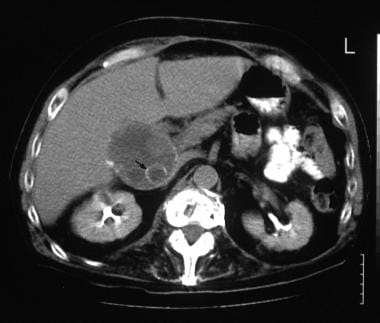

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a polypoid mass in the gallbladder where the curvilinear calcification is fragmented (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a polypoid mass in the gallbladder where the curvilinear calcification is fragmented (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a break in the gallbladder wall (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a break in the gallbladder wall (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

Calcification in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen has several causes. Calcification can be categorized by the organ system in which it appears; for example, calcification can affect the liver, gallbladder, right kidney, digestive tract, peritoneal cavity, right adrenal gland, and retroperitoneum. Diseases that are associated with these organs include large gallbladder opaque calculi, milk-of-calcium bile, echinococcal cysts, schistosomiasis and other granulomatous disease, old liver infarcts that have healed, calcified renal cysts, renal calculi, calcified nonparasitic liver cysts, primary and metastatic liver tumors, benign liver tumors, and calcification in old adrenal hemorrhage and adrenal masses.

Although calcification seen on plain abdominal images can possibly be confused with porcelain gallbladder, the anatomic location, as viewed on CT scans, depicts calcification in the gallbladder fossa. This finding is less likely to create confusion with other findings of upper abdominal calcification.

Ultrasonography

Although plain abdominal radiographs have been the standard technique for demonstrating right upper quadrant calcification, sonograms appear to be more sensitive than radiographs. [27, 30] Four distinct patterns have been identified in ultrasonography of porcelain gallbladder, and they are as follows: (1) a hyperechoic semilunar structure with posterior acoustic shadowing that simulates a stone-filled gallbladder devoid of bile (see first image below), (2) a biconvex curvilinear echogenic structure with variable acoustic shadowing, (3) an irregular clump of echoes with posterior acoustic shadowing (see second image below), and (4) an echogenic gallbladder wall without acoustic shadowing. In addition, a spiral image may show findings similar to those seen in scleroatrophic gallbladder lithiasis. [31]

On this sonogram in the same patient, a calcified gallbladder mass appears as a hyperechoic semilunar structure with complete, posterior acoustic shadowing. The appearance is similar to that of a scarred gallbladder filled with calculi.

On this sonogram in the same patient, a calcified gallbladder mass appears as a hyperechoic semilunar structure with complete, posterior acoustic shadowing. The appearance is similar to that of a scarred gallbladder filled with calculi.

A sonogram obtained through the gallbladder fossa that shows an irregular clump of echoes with partial shadowing (same patient with nonbiliary symptoms ).

A sonogram obtained through the gallbladder fossa that shows an irregular clump of echoes with partial shadowing (same patient with nonbiliary symptoms ).

In porcelain gallbladder, plain radiographic findings are usually straightforward and are not often confused with findings related to other causes of calcification in the right upper quadrant. If doubt exists, cross-sectional imaging with a modality such as ultrasonography or CT can more accurately depict calcification in the appropriate organ. [27, 32, 33] Porcelain gallbladder must be distinguished from large solitary calcified gallstones, which seldom are as large as a porcelain gallbladder; however, exceptions can make a definite diagnosis difficult.

Confusion may also arise with emphysematous cholecystitis and a stone-filled gallbladder when only sonographic criteria are used; however, emphysematous cholecystitis usually causes dirty shadowing, which may be interrupted by ring-down shadows caused by gas within the wall or lumen of the gallbladder. A stone-filled gallbladder results in the wall-echo-shadow sign. The wall-echo-shadow sign consists of 2 parallel echogenic lines separated by a hypoechoic space with distal shadowing. The more superficial echogenic line is a result of the interface of the gallbladder wall and the liver; the hypoechoic area is the gallbladder wall itself. The deep echogenic line is the anterior surface of the gallstone(s).

Angiography

Angiography is useful when findings are complicated by carcinoma of the gallbladder. Although carcinoma tends to be avascular, angiography can be used to evaluate the hepatic artery and portal vein for occlusion and/or encasement. This information is useful when surgery is contemplated.

Angiography is used for root mapping of the blood supply of the liver and gallbladder, for which angiography has good accuracy. Portal venous and/or hepatic arterial occlusion or encasement also can be demonstrated fairly well on angiograms.

Hepatic arterial and/or portal venous occlusion or encasement can occur as a consequence of benign inflammatory diseases such as pancreatitis.

-

A plain abdominal radiograph that shows a right upper quadrant pyriform opaque mass with curvilinear calcification; this finding suggests porcelain gallbladder.

-

On this sonogram in the same patient, a calcified gallbladder mass appears as a hyperechoic semilunar structure with complete, posterior acoustic shadowing. The appearance is similar to that of a scarred gallbladder filled with calculi.

-

This CT scan obtained in a patient with nonbiliary symptoms shows a partial gallbladder wall calcification that suggests porcelain gallbladder.

-

A sonogram obtained through the gallbladder fossa that shows an irregular clump of echoes with partial shadowing (same patient with nonbiliary symptoms ).

-

A transaxial enhanced CT scan of a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed.

-

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder, which is associated with a gallbladder calculus (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

-

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a polypoid mass in the gallbladder where the curvilinear calcification is fragmented (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

-

A transaxial enhanced CT scan in a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a break in the gallbladder wall (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed in the same patient (a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain).

-

This plain abdominal radiograph shows milk-of-calcium bile and a calculus that obstructs the Hartmann pouch.

-

A plain radiograph of the right upper quadrant that shows curvilinear calcification in 2 hydatid cysts in a patient from a region in which hydatid disease is endemic.

-

This transaxial CT scan of the liver shows a calcified hydatid cyst, which can mimic porcelain gallbladder.

-

A plain abdominal radiograph of the right upper quadrant of a patient with a history of a hepatic injury that occurred 10 years ago shows curvilinear calcification in 2 mass lesions in the right lobe of the liver.