Practice Essentials

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI), defined as gas in the bowel wall, is often first identified on abdominal radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans. It is a radiographic finding and not a diagnosis, as the etiology varies from benign conditions to fulminant gastrointestinal disease. Pneumatosis intestinalis is considered an ominous finding in ischemia, especially in association with portomesenteric venous gas. The disease is seen in other conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, connective tissue disorders, infectious enteritis, celiac disease, leukemia, amyloidosis, and AIDS [1] In neonates, PI is s diagnostic of necrotizing enterocolitis and is associated with a high mortality. [2]

Pneumatosis intestinalis is usually identified on plain radiographs of the abdomen. Occasionally, submucosal cysts may be identified during endoscopy. The cysts, which may appear similar to polyps, may be examined at biopsy for signs of inflammation. Gas may collect peripherally in the lumen of the bowel, around fecal or contrast material. This gas can simulate pneumatosis and is usually depicted on CT scans. [3] Rarely, emphysematous ureteritis may simulate pneumatosis of the descending or sigmoid colon on plain radiographs. Colitis cystica profunda is an extremely rare disease in which mucin-filled cysts form in the wall of the rectum. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful for identifying intestinal ischemia as a cause of pneumatosis. High signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images suggests ischemia. Gas bubbles within the bowel wall have been described on abdominal MRI scans of neonates with necrotizing enterocolitis. [3, 4, 5]

(See the images below.)

Benign cystic pneumatosis. Radiograph from a barium enema study demonstrates rounded, lucent filling defects in the right side of the colon.

Benign cystic pneumatosis. Radiograph from a barium enema study demonstrates rounded, lucent filling defects in the right side of the colon.

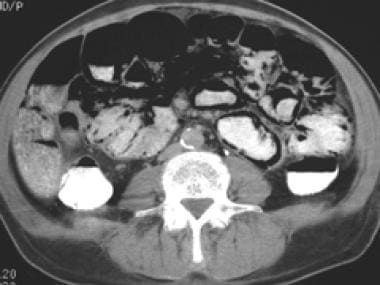

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a soft-tissue window in a patient with intestinal ischemia demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis.

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a soft-tissue window in a patient with intestinal ischemia demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis.

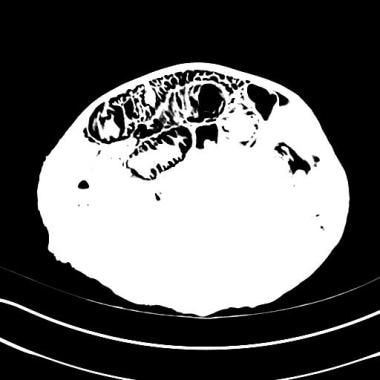

Three-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with ischemic bowel demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis intestinalis.

Three-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with ischemic bowel demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis intestinalis.

PI is usually managed conservatively, with surgical intervention only if signs and symptoms are present. Surgery should be performed in patients who are not responding to nonoperative treatment, especially those with signs of perforation, peritonitis, or abdominal sepsis. [2]

Primary versus secondary pneumatosis intestinalis

Pneumatosis intestinalis occurs in 2 forms. Primary pneumatosis intestinalis (15% of cases) is a benign idiopathic condition in which multiple thin-walled cysts develop in the submucosa or subserosa of the colon. Usually, this form has no associated symptoms, and the cysts may be found incidentally through radiography or endoscopy. When the cysts protrude into the lumen, they may mimic polyps or carcinomas, as shown on barium enema studies. This primary form is often termed pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI). [6] The secondary form (85% of cases) is associated with obstructive pulmonary disease, as well as with obstructive and necrotic gastrointestinal disease. [2]

Microvesicular gas collections, defined as 10-100 mm cysts or bubbles within the lamina propria, are predominantly associated with primary (benign) pneumatosis intestinalis, whereas linear or curvilinear gas collections seen parallel to the bowel wall are found in secondary pneumatosis. Therefore, linear gas collections are usually an ominous sign.

Radiography

The patterns of the radiolucencies are seen as linear, curvilinear, small bubbles, or collections of cysts. Cystic collections of gas localized to the wall of the colon are suggestive of primary pneumatosis intestinalis. Pneumatosis intestinalis may be complicated by pneumoperitoneum, which can be detected as free air on a simple upright or cross-table lateral view of the abdomen.

Pneumoperitoneum may represent rupture of subserosal cysts in benign primary pneumatosis, or it may occur after perforation in the setting of intestinal necrosis. Linear or curvilinear gas collections may be seen throughout the intestinal wall in secondary pneumatosis. Portal venous gas, which is tubular and peripherally located in the liver (as opposed to biliary air, which is centrally located), is an ominous finding, often occurring with ischemic bowel. [7]

Abdominal radiographic findings are detected in approximately two thirds of patients with pneumatosis. Radiographs are sufficient for diagnosis of pneumatosis, although additional studies, such as CT scans, ultrasonograms, or water-soluble enema studies, may be considered to delineate pneumatosis or the site of perforation. The concomitant finding of portal venous gas does not always suggest bowel ischemia. Other etiologies must be clinically correlated with the patient's history. The presence of gas in the mesenteric and portal circulation is an ominous radiographic finding in bowel ischemia. Rarely, emphysematous ureteritis may simulate pneumatosis of the descending or sigmoid colon on plain radiographs. Angiography can provide insight into the nature of vascular compromise.

(See the images below.)

Benign cystic pneumatosis. Radiograph from a barium enema study demonstrates rounded, lucent filling defects in the right side of the colon.

Benign cystic pneumatosis. Radiograph from a barium enema study demonstrates rounded, lucent filling defects in the right side of the colon.

Computed Tomography

Abdominal CT is the most sensitive imaging technique for the diagnosis of PI. [8] Abdominal CT scanning can depict small amounts of intramural gas not shown on routine radiographs. Depending on the morphology, distention, and thickness of the bowel loops, CT scanning helps provide clues to the cause of pneumatosis intestinalis. [9]

A study that compared the CT findings in patients with benign or life-threatening PI showed that certain CT features, including mesenteric stranding, bowel wall thickening, and ascites, were present in more than 90% of patients with severe PI and correlated significantly with life-threatening disease. [3] The presence of hepatoportal or portomesenteric venous gas and a linear pattern of intramural gas are associated with intestinal infarction, but portal venous gas or pneumoperitoneum has been seen in a patient with benign PI. [10] The lesion area in PI may also be important. In about half of all patients with life-threatening PI, the main PI lesion area is confined to the small intestine, whereas about 70% of patients with benign PI show colonic involvement. However, these findings are not specific or definitive characteristics of life-threatening PI because these CT findings, including mesenteric stranding, bowel wall thickening, and ascites, are also observed in about 50% of patients with benign PI. [3]

(See the images below.)

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a soft-tissue window in a patient with intestinal ischemia demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis.

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a soft-tissue window in a patient with intestinal ischemia demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis.

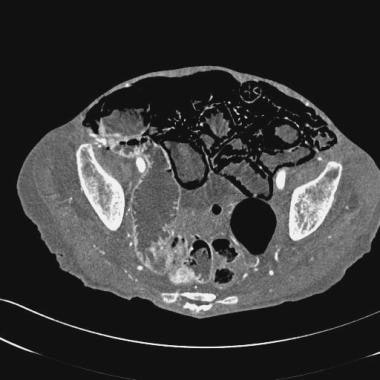

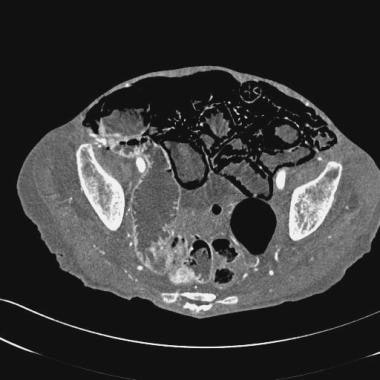

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a lung window in a patient with ischemic bowel more easily demonstrates circumferential pneumatosis intestinalis than do scans obtained with other settings.

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a lung window in a patient with ischemic bowel more easily demonstrates circumferential pneumatosis intestinalis than do scans obtained with other settings.

Three-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with ischemic bowel demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis intestinalis.

Three-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with ischemic bowel demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis intestinalis.

CT scanning is often helpful in determining the primary cause of pneumatosis intestinalis, and it can demonstrate important coexistent findings or complications. The use of multidetector-row CT scans, thin sections, and high-quality portal venous phase scans are advantageous for providing greater accuracy in the detection of ischemia, as well as for diagnosing other causes of acute abdomen, such as perforation, abscess formation, and peritonitis. The sensitivity of CT scanning (82%) for the diagnosis of acute bowel ischemia has been shown to be comparable to that of angiography (87.5%). [3]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography of the abdomen shows within the bowel wall circumferential, bright, echogenic foci that represent the gas bubbles. The pattern of gas distribution, particularly within the dependent wall, should raise the suspicion of pneumatosis intestinalis in a patient with the appropriate clinical history. [7]

Case reports of the use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to diagnose pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis has been published. The advantages over CT have included the lack of radiation and the fact that it can be performed during the same session as colonoscopy. If a miniaturized probe is used, all the segments of the colon can be easily explored. [8]

Misregistration artifact occurs only on the nondependent wall and usually involves the superficial wall layers, in contrast to pneumatosis intestinalis, which is typically circumferential and often has a submucosal or subserosal location.

In addition to the familiar artifacts of dirty shadowing and small reverberation artifacts, a bubble of intraluminal gas may falsely lie within the gut wall, producing an artifact called pseudopneumatosis. It is more likely seen with thickening of the gut wall.

-

Benign cystic pneumatosis. Radiograph from a barium enema study demonstrates rounded, lucent filling defects in the right side of the colon.

-

Radiograph in a patient with ischemic bowel demonstrates linear pneumatosis intestinalis.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a soft-tissue window in a patient with intestinal ischemia demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan in a lung window in a patient with ischemic bowel more easily demonstrates circumferential pneumatosis intestinalis than do scans obtained with other settings.

-

Three-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with ischemic bowel demonstrates circumferential small bowel pneumatosis intestinalis.

-

Pneumatosis of the right colon in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

-

Benign small bowel pneumatosis in a patient with multiple myeloma secondary to amyloidosis.

-

Radiograph in a patient with intestinal ischemia demonstrates portal venous gas.

-

Nonenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with intestinal ischemia demonstrates portal venous gas.

-

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in an infant. Pneumatosis is usually secondary to NEC in newborns.