Practice Essentials

Placenta previa is a condition in which the placental tissue lies abnormally close to the internal cervical os. The 4 generally recognized subtypes are as follows [1, 2, 3] :

-

Complete or total, in which the placenta covers 360° of the internal cervical os.

-

Incomplete or partial, in which 0°-360° of the internal cervical os is covered by placental tissue.

-

Marginal, in which the placental tissue abuts but does not cover the internal cervical os.

-

Low lying, in which the edge of the placenta lies abnormally close to but does not abut the internal cervical os.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) suggests describing the relationship between the placenta and internal cervical os. [4, 5, 6, 7]

Placenta previa occurs in 0.3-2.0% of all births. This range in the reported incidence results from differing definitions, methods of diagnosis, and gestational ages at the time of diagnosis. In addition, the frequency varies among different patient populations. In the United States, the incidence of placenta previa is reported to be slightly higher in minority populations. Increased maternal age is a known risk factor for placenta previa. [1, 2, 3]

(See the images below.)

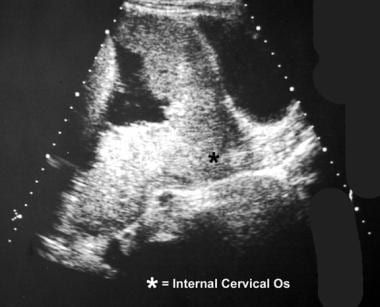

Ultrasonogram shows asymmetric complete placenta previa. Follow-up examination should be performed after the patient has voided to prevent false-positive results. An overdistended bladder may have the appearance of placenta previa. This finding is more common when the placenta is anterior.

Ultrasonogram shows asymmetric complete placenta previa. Follow-up examination should be performed after the patient has voided to prevent false-positive results. An overdistended bladder may have the appearance of placenta previa. This finding is more common when the placenta is anterior.

The reported incidence of placenta previa in the second trimester is nearly 10 times that at delivery. Various explanations have been proposed to account for this difference. The most likely theory suggests that during the third trimester, the lower uterine segment elongates more than the placenta enlarges. Thus, a placenta that appears marginal or low lying at 20 weeks may be normally positioned at term. Results of most investigations of this phenomenon, however, indicate that a complete placenta previa in the second trimester rarely reverts to a normal position at term.

Historically, placenta previa was diagnosed by means of digital palpation of the placental tissue through the cervical canal. The slightest amount of manipulation, however, may result in a substantial amount of hemorrhage. Physical examination should be performed only with a fetus that has achieved pulmonary maturity and only in a fully staffed operating room. Maternal bleeding may be so severe that immediate delivery is necessary.

Imaging modalities

Transvaginal ultrasonography is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of placenta previa. Some clinicians advocate insertion of the probe no more than 3 cm for visualization of the placenta to avoid inadvertent insertion into the cervical os. Transvaginal ultrasonographic techniques can also be used to evaluate the cervical length, when indicated. On ultrasonography, if the internal cervical os can be visualized and if no placental tissue overlies it, placenta previa is excluded. The cervix should be no longer than 3-3.5 cm during the third trimester. If the cervical length exceeds 3.5 cm or if a falsely elongated cervix is suspected, further imaging should be performed after the patient empties her bladder. With a qualified operator, ultrasonography is more than 95% accurate. [8, 9, 10, 11]

Transabdominal ultrasonography is a simple, precise, and safe method to visualize the placenta that can often be used in conjunction with TVS when available. This imaging modality can also be used as an alternative to TVS; however, it is less accurate. [9, 10, 11]

Usually, the placenta is relatively homogeneous, and signal intensity on T1-weighted spin-echo images on MRI is low and slightly higher than that of the myometrium. On T2-weighted spin-echo images, placental tissue has high signal intensity, and it is clearly distinguishable from the adjacent fetus, uterus, and cervix. [12, 13, 14, 15, 16] In a study by Romeo et al, MRI demonstrated a higher diagnostic accuracy than ultrasound in detecting placental adhesion spectrum in placenta previa. [17] Maurea et al also found MRI to be a useful imaging technique to assess placental adhesion disorders. Of the abnormal MRI signs, intraplacental dark bands and focal interruption of myometrial border were those highly correlated with histologic proof of placental adhesion disorders. [18]

Guidelines/recommendations

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada have published the following guidelines and recommendations [1] :

-

History of antepartum hemorrhage (first episode < 29 wk or recurrent episodes [≥3]), a thick placental edge covering (or close to) the cervical os, short cervical length (< 3 cm with placenta previa, < 2 cm with low-lying placenta), and a previous cesarean delivery are risk factors with an associated increased risk of urgent/preterm cesarean delivery.

-

Preoperative bedside ultrasound assessment of placental location can be useful for planning of surgical technique and may reduce risk of intraoperative transection of placenta.

-

When deciding the location of delivery, consider ultrasound assessment of placental location, any risk factors, the patient's history, and logistical factors, including available resources at the delivery unit.

-

Classify placental location as placenta previa (placenta covering the cervical os), low-lying placenta (edge located ≤20 mm from cervical os), or normally located placenta (edge located >20 mm from cervical os).

-

Diagnosis of placenta previa or low-lying placenta should not be made < 18 to 20 wk gestation, and the provisional diagnosis must be confirmed after >32 wk gestation, or earlier if the clinical situation warrants. In women with a low-lying placenta, a recent ultrasound (within 7-14 days) should be used to confirm placental location before a cesarean delivery.

-

Assessment by transvaginal ultrasound is recommended in all cases where placenta previa or a low-lying placenta is present or suspected by transabdominal ultrasonography, with attempt to clearly define placental location (including laterality), characteristics of placental edge (including thickness, presence of a marginal sinus), and associated findings (succenturiate lobe, cord insertion close to the cervix).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Usually, the placenta is relatively homogeneous. Its signal intensity on T1-weighted spin-echo images is low and slightly higher than that of the myometrium. On T2-weighted spin-echo images, placental tissue has high signal intensity, and it is clearly distinguishable from the adjacent fetus, uterus, and cervix. Sagittal images best demonstrate the placental position in relation to the internal cervical os. Occasionally, endometrial veins may be seen at the margins of the placenta. Normal physiologic placental calcifications, which occur during late pregnancy, usually are not seen on MRIs.

The diagnosis of placenta previa is established on finding that placental tissue covers all or part of the internal cervical os. [19, 20, 21, 12, 22, 13, 14, 15, 16]

(See the image below.)

Accuracy

MRI has been used to evaluate placental location in a number of studies. Its accuracy is equivalent to and may even surpass that of ultrasonography.

False-positive findings may result from myometrial contraction in the lower uterine segment at imaging. Although the placental margin remains distinct from the contracted muscle and the internal cervical os, the distance between the placental margin and the os may decrease, leading to a false diagnosis of a low-lying placenta. In extreme cases, the edge of the placenta might come in contact with or even overlie a portion of the internal cervical os and thereby mimic placenta previa.

In a study by Romeo et al, MRI demonstrated a higher diagnostic accuracy than ultrasound in detecting placental adhesion spectrum in placenta previa. [17]

Maurea et al also found MRI to be a useful imaging technique to assess placental adhesion disorders. Of the abnormal MRI signs, intraplacental dark bands and focal interruption of myometrial border were those highly correlated with histologic proof of placental adhesion disorders. [18]

Imaging pearls

In the case of pure placenta previa (ie, placenta previa that is not complicated by placenta accreta), the radiologist nearly always plays a solely diagnostic role. Occasionally, the interventionalist may be called upon to embolize the uterine arteries after cesarean delivery. If hemorrhage cannot be controlled surgically, this procedure may obviate emergency hysterectomy. [23]

Failure to diagnose placenta previa may have grave consequences during the later trimesters and at the time of delivery. The relatively high incidence of placenta previa during the second trimester should not lead the radiologist to fail to diagnose this condition. Whenever the diagnosis is suspected in the second trimester, further evaluation is recommended. In nearly all cases, this evaluation involves repeat ultrasonography during the third trimester.

Care should be taken not to mistake a more serious situation, such as placental abruption or placenta accreta, for placenta previa, because the management of these conditions is different. In addition, the radiologist must avoid satisfaction-of-search errors. The possibility of one of these diagnoses complicating placenta previa must be excluded.

The likelihood of congenital anomalies and transverse fetal positioning is slightly higher in patients with placenta previa than in others.

The long-term effects of exposure to a static magnetic field and rapidly shifting gradients on fetal development have not been fully evaluated.

The time required to arrange and perform an adequate examination may limit its usefulness, particularly in the setting of acute maternal hemorrhage.

MRI should be used only after ultrasonography fails to provide adequate information. [24]

Ultrasonography

Transvaginal ultrasonography is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of placenta previa. Some clinicians advocate insertion of the probe no more than 3 cm for visualization of the placenta to avoid inadvertent insertion into the cervical os. If the internal cervical os can be visualized and if no placental tissue overlies it, placenta previa is excluded. The cervix should be no longer than 3-3.5 cm during the third trimester. If the cervical length exceeds 3.5 cm or if a falsely elongated cervix is suspected, further imaging should be performed after the patient empties her bladder. With a qualified operator, ultrasonography is more than 95% accurate. [8, 9, 10, 11]

Transabdominal ultrasonography is a simple, precise, and safe method to visualize the placenta that can often be used in conjunction with TVS when available. It can be used as an alternative to transvaginal ultrasonography but is less accurate. [9, 10, 11]

An attempt must be made to identify the inferior-most aspect of the placenta and to determine the distance between it and the internal os. When the fetal head obscures a posteriorly positioned placenta or when the inferior placental margin is not visualized with transabdominal imaging, a transvaginal or transperineal approach is nearly always adequate in revealing its position.

(See the images below.)

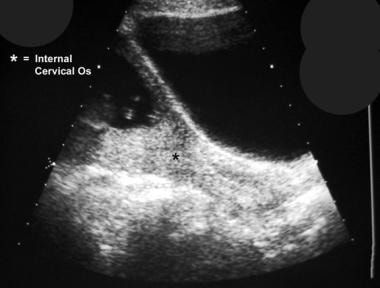

Ultrasonogram shows asymmetric complete placenta previa. Follow-up examination should be performed after the patient has voided to prevent false-positive results. An overdistended bladder may have the appearance of placenta previa. This finding is more common when the placenta is anterior.

Ultrasonogram shows asymmetric complete placenta previa. Follow-up examination should be performed after the patient has voided to prevent false-positive results. An overdistended bladder may have the appearance of placenta previa. This finding is more common when the placenta is anterior.

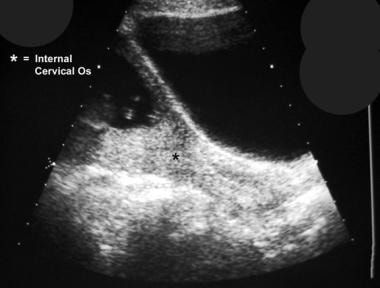

Postvoiding longitudinal sonogram shows that the findings in a patient are not related to an overdistended bladder but rather to a true placenta previa.

Postvoiding longitudinal sonogram shows that the findings in a patient are not related to an overdistended bladder but rather to a true placenta previa.

Although diagnostic criteria may vary among institutions, any of the following findings excludes placenta previa: direct apposition of the presenting part of the fetus and the cervix without space for interposed tissue; the presence of amniotic fluid between the presenting part of the fetus and the cervix, without the presence of placental tissue; and a distance of greater than 2 cm between the inferior aspect of the placenta and the internal cervical os on direct visualization. [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 14, 16]

The conditions that are most commonly misdiagnosed as placenta previa are an overdistended bladder and myometrial contractions. Overdistention of the maternal urinary bladder places pressure on the anterior aspect of the lower uterine segment, compressing it against the posterior wall and causing the cervix to appear elongated. Thus, a normal placenta may appear to overlie the internal os. The cervix should be no longer than 3-3.5 cm during the third trimester. If the cervical length exceeds 3.5 cm or if a falsely elongated cervix is suspected, further imaging should be performed after the patient empties her bladder. Because transvaginal and transperineal imaging is performed when the patient's bladder is empty, this pitfall should occur only rarely.

During a myometrial contraction, 2 situations that mimic placenta previa may occur: First, the wall of the uterus may thicken and imitate placental tissue. Second, the lower uterine segment may shorten and bring the inferior edge of the placenta into contact with the internal cervical os, creating a condition that mimics placenta previa. To avoid this pitfall, a contraction should be suspected if the myometrium is thicker than 1.5 cm. Findings from repeat imaging performed after 30 minutes should be sufficient to exclude this condition.

Accuracy

With a qualified operator, sonography is more than 95% accurate. Transvaginal evaluation of the placenta has a 1% false-positive rate and a 2% false-negative rate. Hertzberg and colleagues reported a 100% negative predictive value for transperineal sonography in a study of 164 patients. [32]

Transabdominal sonography is the test of choice to confirm placenta previa. When the internal cervical os cannot be visualized or when the results are inconclusive, transperineal or transvaginal sonography is recommended as an adjunct. The overall accuracy of ultrasonography in the evaluation of placenta previa has been reported to be 93-98%. Transperineal studies have a negative predictive value of nearly 100% for this diagnosis. No increased risk of hemorrhage has been associated with transvaginal or transperineal sonography in this clinical setting. [14, 15, 33, 34, 35]

Imaging pearls

Care should be taken when diagnosing placenta previa during the second trimester. This condition is reported to be 10-100 times as common in the second trimester as it is at term. Although the underlying physiology remains somewhat controversial, the disparity remains a fact. When placental tissue lies near or over the internal os in the second trimester, repeat imaging should be performed at a later date to confirm the diagnosis.

In the case of pure placenta previa (ie, placenta previa that is not complicated by placenta accreta), the radiologist nearly always plays a solely diagnostic role. Occasionally, the interventionalist may be called upon to embolize the uterine arteries after cesarean delivery. If hemorrhage cannot be controlled surgically, this procedure may obviate emergency hysterectomy. [23]

Failure to diagnose placenta previa may have grave consequences during the latter trimesters and at the time of delivery. The relatively high incidence of placenta previa during the second trimester should not lead the radiologist to fail to diagnose this condition. Whenever the diagnosis is suspected in the second trimester, further evaluation is recommended. In nearly all cases, this evaluation involves repeat sonography during the third trimester.

Care should be taken not to mistake a more serious situation, such as placental abruption or placenta accreta, for placenta previa, because the management of these conditions is different. In addition, the radiologist must avoid satisfaction-of-search errors. The possibility of one of these diagnoses complicating placenta previa must be excluded.

The likelihood of congenital anomalies and transverse fetal positioning is slightly higher in patients with placenta previa than in others. Special care should be taken to document such findings.

The major limitation of sonography in the diagnosis of placenta previa is related to the gestational age at diagnosis.

-

Longitudinal transabdominal sonogram demonstrates complete symmetric placenta previa.

-

Ultrasonogram shows asymmetric complete placenta previa. Follow-up examination should be performed after the patient has voided to prevent false-positive results. An overdistended bladder may have the appearance of placenta previa. This finding is more common when the placenta is anterior.

-

Postvoiding longitudinal sonogram shows that the findings in a patient are not related to an overdistended bladder but rather to a true placenta previa.

-

Sagittal T2-weighted image (SSFSE) depicts a complete placenta previa in this 28-week pregnancy.