Practice Essentials

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is characterized by progressive pancreatic damage that eventually leads to impairment of both exocrine and endocrine functions of the pancreas. [1] Specific risk factors for CP include alcohol and smoking, genetics, and obstructive diseases. In 10-30% of patients, no identifiable causitive factor for CP is found. [2]

The most common cause of chronic pancreatitis in Western societies is alcohol abuse and accounts for 50% of cases of CP in the United States. [2] However, a recent study found that moderate alcohol intake (less than 2 drinks per day) was protective against recurrent acute and CP. [3] An association between genetic variants of CLDN2 in alcoholic patients has been proposed as second risk factor in alcoholics. CLDN2 is an X-linked gene that encodes the protein Claudin-2, which is highly expressed by pancreatic acinar cells during stressful conditions, and may contribute to pathologic inflammation of CP.31 [2]

The most common symptom of CP is abdominal pain, usually epigastric, dull and constant in nature. It is almost always localized in the upper half of the abdomen and radiates directly through to the back, or laterally around to the left or right flank. Initially the duration of pain ranges from several hours to several days, but as the disease progresses the attacks become more frequent and pain-free intervals shrink. However, pain can be absent in CP and patients present with steatorrhea, weight loss and diabetes caused by exocrine or endocrine insufficiency. [1]

Less common initial presentations include biliary obstruction with recurrent episodes of mild jaundice, cholangitis, or vague attacks of indigestion. Obstruction of the splenic vein by an inflamed tail of the pancreas can lead to left-sided portal hypertension, gastric varices and GI bleeding. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer may present in a similar manner, making it difficult to distinguish between them. [1, 2]

A diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is difficult to establish, especially in the early stages of disease. Typical symptoms such as weight loss, pain, steatorrhea, and malnutrition are vague and nonspecific. The diagnosis of CP is based on a combination of clinical history, risk factors, imaging, endoscopy, and pancreatic function testing. [1, 2]

Various imaging modalities are used to diagnose CP including endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), computerized tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Pancreatic calcifications are pathognomonic for severe CP and are located exclusively in the ductal system. The diagnosis of advanced CP is usually straightforward; however, the diagnosis of early, mild, non-calcific, or minimal change CP is challenging. The accurate diagnosis of CP in its early stages remains difficult for many reasons, including an inability to differentiate pancreatic versus nonpancreatic chronic upper abdominal, the lack of consensus on the degree of histological changes needed to diagnose chronic pancreatitis, and the fact that advanced imaging (EUS and secretin-stimulated magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) and endoscopic pancreatic function tests can be abnormal in asymptomatic patients who are older, obese, smoke, and/or use alcohol. [4]

(See the images of chronic pancreatitis below.)

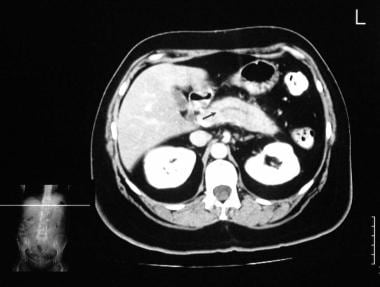

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas, associated with a 4-cm pseudocyst to the right of the head of the pancreas.

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas, associated with a 4-cm pseudocyst to the right of the head of the pancreas.

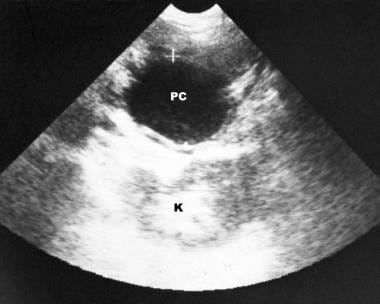

Chronic pancreatitis. Transverse sonogram shows an echogenic, enlarged pancreas with multiple small hyperechoic nonshadowing foci in the pancreas.

Chronic pancreatitis. Transverse sonogram shows an echogenic, enlarged pancreas with multiple small hyperechoic nonshadowing foci in the pancreas.

Distinct classification systems have been developed for CP, but only the Toxic/metabolic, Idiopathic, Genetic, Autoimmune, Recurrent acute pancreatitis, and Obstructive (TIGAR-O) and the M-ANNHEIM classification systems take the etiology of CP into account.

In the TIGAR-O system, the major risk factors for the development of chronic pancreatitis are categorized as follows:

-

T: toxic-metabolic (e.g. alcohol)

-

I: idiopathic (cystic fibrosis must be ruled out in these patients before diagnosis is made) [5]

-

G: genetic (more commonly seen in the pediatric population)

-

A: autoimmune

-

R: recurrent

-

O: obstructive (e.g. choledocholithiasis, pancreatic head tumour)

In the M-ANNHEIM system, the stage, severity and clinical findings of CP are integrated. The M-ANNHEIM system is the only one offering a severity index and is used accordingly. After a complex procedure, a score of between 0–25, representing the severity of CP, is calculated. [5]

Chronic pancreatitis can also be classified into 3 categories:

-

Chronic calcifying pancreatitis

-

Chronic obstructive pancreatitis

-

Chronic inflammatory pancreatitis

Chronic calcifying pancreatitis

Chronic calcifying pancreatitis is invariably related to alcoholism. The earliest finding is precipitation of proteinaceous material in the pancreatic ducts that forms protein plugs that subsequently calcify. The ducts and lobules are initially involved in a random manner, and they are surrounded by normal parenchymal tissue. However, as the disease progresses, these normal areas become more diffuse. The pancreatic ductal epithelium undergoes atrophy, hyperplasia, and metaplasia at the site of the protein plugs. Many of the small pancreatic ductules dilate, while others are obliterated by fibrosis.

The main pancreatic duct shows a chain-of-lakes appearance due to alternating stenoses and dilatation. In approximately 50% of patients with chronic calcific pancreatitis, the pancreatic parenchyma contains cysts of varying sizes (several millimeters to 5 cm). These cysts are lined by cuboidal epithelium and contain pancreatic enzymes. Peripancreatic fibrosis is usually a late finding that involves the portal and/or splenic veins. Peripancreatic fibrosis causes stenosis or occlusion of retroperitoneal lymph channels. Ascites may complicate chronic calcific pancreatitis as a result of portal hypertension or lymphatic obstruction in 1-2% patients.

Chronic obstructive pancreatitis

In chronic obstructive pancreatitis, the prominent histologic changes are periductal fibrosis and subsequent ductal dilatation. These changes are much more focal than those in the other forms, and in most patients, the changes involve only the portion of the pancreas in which ductal drainage is impaired. Diffuse changes may occur, in which the main pancreatic duct or ampulla is obstructed. Although protein inspissation may occur, histologic changes in the ductal mucosa are less common, and calcification is unusual. Moreover, the pancreatic duct is dilated, and the pancreas is normal in size, atrophic, or focally and/or globally enlarged. A variety of factors are implicated in chronic obstructive pancreatitis; these include ductal obstruction due to ampullary stenosis, inflammatory or neoplastic causes, surgical ductal ligation, and fibrosis due to a pseudocyst as a complication of an episode of acute pancreatitis.

Chronic inflammatory pancreatitis

Chronic inflammatory pancreatitis is rare and can affect elderly persons without a previous history of alcohol excess.

Autoimmune pancreatitis

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a distinct form of chronic pancreatitis characterized clinically by frequent presentation with obstructive jaundice with or without a pancreatic mass, histologically by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and fibrosis, and therapeutically by a dramatic response to steroids. The International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC) for AIP has proposed two distinctive type of AIP, type 1 and type 2. [6]

Type 1 AIP is believed to be the pancreatic manifestation of an IgG4 related systematic disease and is often accompanied with some extrapancreatic lesions, such as sclerosing cholangitis, sclerosing sialadenitis, and retroperitoneal fibrosis. This type of AIP usually presents with obstructive jaundice in elderly male subjects and responds well to steroid therapy. [7]

Type 1 and 2 share some features in histopathology, such as periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and storiform fibrosis. Type 2 has no or few IgG4-positive cells and seems to be a pancreatic-specific disorder and is not associated with other organ involvement. Patients with type 2 are often a decade younger and do no show gender preference. [7]

The diagnosis of AIP depends on serum IgG4 concentration, pancreatic histology, pancreatic parenchymal and duct imaging, other organ involvement, and steroid reaction. [7]

Preferred examination

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) provides the most accurate visualization of the pancreatic ductal system and is considered the gold standard for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis. It combines the use of endoscopy and fluoroscopy to visualize and treat problems of the biliary and pancreatic ducts.

ERCP is considered a sensitive test for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, having the ability to show dilation or stricture of the pancreatic duct and its branches, as well as early features of chronic pancreatitis. ERCP provides therapeutic options, such as dilation, stone extraction, and stenting of the duct. An additional benefit is the possibility of procuring pancreatic juice during ERCP. [1] However, ERCP is invasive, expensive, and time consuming and can only evaluate for ductal changes. The use of ERCP is generally reserved for patients in whom the diagnosis remains inconclusive despite pancreatic function testing CT/MRI or EUS. [2] Angiography is reserved for patients with suspected complications resulting from chronic pancreatitis.

Ultrasonography is the first modality to be used in patients presenting with upper abdominal pain, although the direct diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is not always possible. Sonography can help in determining the cause of chronic pancreatitis (eg, alcoholic liver disease, calculus disease) and in assessing the complications of the disease (eg, pseudocysts, ascites, splenic/portal venous obstruction). [8]

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an important imaging modality to detect early morphologic changes in CP. It can detect mild parenchymal and ductal changes not seen on CT scan, and can be used when CT and MR imaging are non-diagnostic. The most predictive endosonographic feature of chronic pancreatitis is the presence of stones. [2]

The Rosemont classification system is designed to standardize the endosonographic assessment of CP and categorize patients undergoing endosonography by the likelihood of having CP on the basis of particular EUS criteria. Major criteria include hyperechoic foci with shadowing and main pancreatic duct calculi, and lobularity with honeycombing. Minor criteria include cysts, dilated ducts ≥3.5 mm, irregular pancreatic duct contour, dilated side branches ≥1 mm, hyperechoic duct wall, strands, nonshadowing hyperechoic foci, and lobularity with noncontiguous lobules. However, these criteria for predicting prognosis and outcome of therapy in patients with chronic pancreatitis is unknown. [9, 10]

EUS, in which the probe can approach the pancreas, is capable of yielding high-resolution visualization of abnormal pancreatic parenchyma and the pancreatic duct that may not be possible with other modalities. Although EUS can detect subtle changes that cannot be detected by other diagnostic imaging modalities, interpretation of the results can be challenging, particularly in early CP, in which interpretation is dependent on examiners and may result in false positives. [11, 12, 13]

One of the greatest limitations in using EUS is the low interobserver agreement. Studies show good agreement in two features, duct dilatation (κ = 0.6) and lobularity (κ = 0.51), but low agreement for the other seven features (κ< 0.4) [83].

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and MRI have also been used to diagnose CP and have the advantage of no radiation exposure. Moreover, MRI has the advantage of detecting both parenchymal and ductal changes. [2] The use of secretin-stimulated magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (s-MRCP) can demonstrate pancreatic exocrine reserve, as well as a "santorinocele" (ie, a dilated Santorini duct seen in pancreas divisum). [14, 15] For the diagnosis of early CP, s-MRCP has a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 83%. [2]

CT is a widely-used imaging modality and while diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis is not reliable, CT should nevertheless be performed in all patients to exclude a mass or gastro-intestinal malignancy. It is excellent for imaging of the retroperitoneum, and it is useful in differentiating chronic pancreatitis from pancreatic carcinoma. [16] In addition, CT may be used in the assessment of chronic pancreatitis-related complications, such as pseudocysts, pseudoaneurysm and duodenal stenosis. Overall, CT remains the best screening tool for detection of chronic pancreatitis and exclusion of other intra-abdominal pathology that may be indistinguishable from chronic pancreatitis based on clinical symptoms. [1]

EUS, ERCP, MRI and CT all have comparable high diagnostic accuracy in the initial diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. EUS and ERCP are outperformers and US has the lowest accuracy. The choice of imaging can be made based on clinical considerations. [17]

Limitations of techniques

On anteroposterior radiographs, the spine may mask small punctate calcifications; therefore, the acquisition of additional oblique or lateral imaging may be indicated.

On sonograms, the pancreas may appear normal even in the presence of advanced disease. In patients who are obese, excessive intraperitoneal gas may obscure the pancreas. Gas overlying the pancreas also can make visualization of the pancreas difficult.

Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma share many features on CT, which makes differentiation difficult. Further, it can be challenging and sometimes impossible to differentiate between the two conditions on US. Gerstenmaier and Malone proposed a diagnostic algorithm based on Bayesian analysis and recommended EUS and fine needle aspiration as next steps when a mass is detected on US or CT. [18]

Anatomy

An understanding of pancreatic anatomy is important in delineating the cross-sectional anatomy of the pancreas and the causation of pain in pancreatic disease. The pancreas varies in shape and lies in the anterior pararenal space. The head of the pancreas lies within the curve of the duodenal loop, and the inferior vena cava and right renal vessels lie posteriorly. The common bile duct receives the main pancreatic duct as it passes through the pancreatic head and then drains into the duodenum at the ampulla.

The gastroduodenal artery may be seen anteriorly at the pancreatic head and neck. The head of the pancreas is the most bulbous part of the gland, which then narrows to the neck. The union of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins, which forms the portal vein posteriorly, marks the anatomic position of the pancreatic neck. The pylorus lies anteriorly. The lesser sac lies anterior to the pancreas, whereas the splenic vein runs along its posterosuperior surface. The tail of the pancreas is related to the spleen, left adrenal gland, and upper pole of the left kidney.

Sonograms of the pancreas typically demonstrate a homogeneous echo pattern, and the pancreas is more echogenic than the liver. The pancreatic head measures 2.5-3.5 cm; the body, 1.75-2.5 cm; and the tail, 1.5-3.5 cm. The size of the pancreas varies considerably; therefore, reliance on size alone can lead to diagnostic errors. Generally, the size of the gland decreases with patient age, while echogenicity increases. The pancreas is more echogenic than the liver in 52% of young adults and equally echogenic in 48%. With the use of modern ultrasonographic machines, the main pancreatic duct can be identified in 85% of patients. On sonograms, the normal duct diameter is 1.3 mm ± 0.3. In patients with gallstones, the average diameter is 1.4 mm.

The typical criteria for pancreatic size on CT scans are the following: the head is 23 mm; neck, 19 mm; body, 20 mm; and tail, 15 mm. By using optimal CT techniques, the pancreatic duct can be identified in just more than 50% of the patients. Normally, the pancreatic diameters demonstrated on CT scans vary from 2-4 mm, but the effect of pixel averaging on normal pancreatic duct measurements is significant and can make such measurements unreliable. Errors of 1 or 2 mm may occur.

In most patients, a normal pancreatic duct is seen on images obtained with T2-weighted short-tau inversion recovery MRI sequences and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

Chronic pancreatitis imaging guidelines

The clinical practice guidelines for the diagnostic cross-sectional imaging and severity scoring of chronic pancreatitis were released in October 2018 by the Working Group for the International Consensus Guidelines for Chronic Pancreatitis and include the following [19] :

-

Computed tomography (CT) is often the most appropriate initial imaging modality to evaluate suspected chronic pancreatitis (CP); it depicts most of the changes in pancreatic morphology.

-

CT is also indicated to exclude other potential intra-abdominal pathologies that present with symptoms similar to those of chronic pancreatitis, but CT cannot exclude a diagnosis of CP and cannot exclusively diagnose early or mild CP.

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are superior and are indicated especially in patients in whom no specific pathologic changes are seen on CT.

-

Secretin-stimulated MRCP is more accurate than standard MRCP to identify subtle ductal changes. Secretin-stimulated MRCP should be performed after a negative MRCP if there is still clinical suspicion of CP.

-

Secretin-stimulated MRCP can provide assessment of exocrine function and ductal compliance.

-

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can also be used to diagnose parenchymal and ductal changes mainly during the early stage of CP.

-

There are no known validated radiologic severity scoring systems for CP, but a modified Cambridge Classification has been used for MRCP.

-

A new and validated radiologic CP severity scoring system is needed that is based on imaging criteria (CT and/or MRI), including glandular volume loss, ductal changes, parenchymal calcifications, and parenchymal fibrosis.

The 2017 United European Gastroenterology guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of chronic pancreatitis (HaPanEU) include the following key imaging recommendations [5] :

-

There is no preferred classification system for defining the etiology of CP since the available classification systems have not been evaluated in randomized prospective trials with endpoints of morbidity and mortality.

-

EUS, MRI, and CT are the best imaging methods for establishing a diagnosis of CP.

-

CT examination is the most appropriate method for identifying pancreatic calcifications, while for very small calcifications non-enhanced CT is preferred.

-

The presence of typical imaging findings for CP with MRI/MRCP is sufficient for diagnosis; however, a normal MRI/MRCP result cannot exclude the presence of mild forms of the disease.

-

The use of IV secretin increases the diagnostic potential of MRCP in the evaluation of patients with known/suspected CP.

-

Duodenal filling (DF) during secretin-stimulated MRCP does not help to evaluate the grade of severity of CP.

-

Abdominal ultrasonography can only be used to diagnose CP at an advanced stage.

-

Ultrasonography can be used in patients with suspected CP complications

-

EUS is the most sensitive imaging technique for the diagnosis of CP, mainly during the early stages of the disease, and its specificity increases with increasing diagnostic criteria.

-

EUS has a potential role in the follow-up of patients with CP in the detection of complications, mainly due to its ability in detecting pancreatic malignancy.

-

EUS-guided fine needle biopsy can be considered as the most reliable procedure for detecting malignancy.

Patient education

For patient education information, see the Liver, Gallbladder, and Pancreas Center, as well as Pancreatitis.

Radiography

Plain radiography

Pancreatic calcifications are a common finding in chronic calcific pancreatitis and are considered pathognomonic for alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Calcification primarily represents intraductal calculi, either in the main pancreatic duct or in the smaller pancreatic ductal radicles. Calcification is punctate or coarse, and it may have a focal, segmental, or diffuse distribution.

(See the radiographic images of chronic pancreatitis below.)

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows coarse calcification in the distribution of the pancreas due to chronic calcific pancreatitis.

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows coarse calcification in the distribution of the pancreas due to chronic calcific pancreatitis.

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows calcification in the pancreas associated with osteomalacia secondary to malabsorption. Note the pseudofracture in the right 11th rib (arrow).

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows calcification in the pancreas associated with osteomalacia secondary to malabsorption. Note the pseudofracture in the right 11th rib (arrow).

Chronic pancreatitis. Upper gastrointestinal tract barium study shows a reverse 3 in the duodenum due to chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic carcinoma can have a similar appearance.

Chronic pancreatitis. Upper gastrointestinal tract barium study shows a reverse 3 in the duodenum due to chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic carcinoma can have a similar appearance.

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows a common bile duct stent in situ and fairly extensive pancreatic calcification.

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows a common bile duct stent in situ and fairly extensive pancreatic calcification.

Upper GI tract barium series

Even in the age of cross-sectional imaging, upper GI tract barium series may provide information that is critical to the treatment of patients with chronic pancreatitis.

Esophageal involvement rarely occurs in chronic pancreatitis, and obstruction is usually the result of mediastinal extension of a pseudocyst. Pancreatic enlargement or a pseudocyst may compress the stomach. Peripancreatic fibrosis may involve the antrum of the stomach or duodenum, resulting in stenosis. The anatomic proximity of the pancreatic head and stomach antrum is constant, and enlargement of the pancreatic head usually causes effacement of the antrum; this has been termed the pad sign. Chronic pancreatitis may cause gastric nodularity and thickening of the mucosal folds; these findings are most prominent on the posterior aspect.

Gastric varices secondary to splenic venous thrombosis may have similar findings. The C loop of the duodenum may be widened because of mass effect from an enlarged pancreatic head, or it may be present as an inverted 3 sign due to traction on the medial wall of the duodenum. In the duodenum, mucosal changes occur, such as spiculation, flattening, or slight nodularity of the mucosal folds of the medial border of the duodenum or concentric narrowing due to periduodenal fibrosis.

Small-bowel changes infrequently occur in chronic pancreatitis. Displacement and stretching may occur as a result of pseudocysts. Small-bowel changes may occur as a result of exudation of pancreatic enzymes during the early stages of chronic pancreatitis, when the pancreatic secretory function is still intact. The enzymes may affect the mesenteric vessels at their roots, causing small-bowel ischemia, fibrotic stricture, and malabsorption pattern. As a result of the close anatomic relationship between the transverse colon and the pancreas, the pancreatic enzymes have direct access to the colon.

Changes in the colon include thickening of the haustral folds due to mucosal edema and luminal narrowing. These changes are usually confined to the inferior haustral row of the transverse colon and the splenic flexure. Rarely, fistula formation may occur. All 3 of these colon findings are best appreciated on barium enema examination.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) provides the most accurate visualization of the pancreatic ductal system and is considered the gold standard for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis. It combines the use of endoscopy and fluoroscopy to visualize and treat problems of the biliary and pancreatic ducts.

Earliest changes are observed in side branches of the pancreatic duct, including dilatation without stenosis, dilatation with downstream stenosis, intraluminal mucosal irregularity, and intraluminal filling defects due to protein plugs or calculi. The number of opacified side branches may be reduced in a focal or diffuse manner because of ductal occlusion. (See the image below.)

Chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram shows a dilated common bile duct (CBD) associated with a stricture of the lower CBD (not well shown on this image) and a dilated ectatic tortuous pancreatic duct. A stent was subsequently placed across the CBD stricture.

Chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram shows a dilated common bile duct (CBD) associated with a stricture of the lower CBD (not well shown on this image) and a dilated ectatic tortuous pancreatic duct. A stent was subsequently placed across the CBD stricture.

In late stages of the disease, changes in the main pancreatic duct are prominent and are similar to those in the side branches, such as ductal dilatation with or without stenosis, short segmental narrowing or long strictures, and intraluminal filling defects due to protein plugs or calculi.

The pancreatic duct may show beading or a chain-of-lakes or string-of-pearls appearance because of alternating stenosis and dilatation of the pancreatic duct.

Small (1-2 cm), round or oval, irregular or well-delineated pancreatic parenchymal cavities may be observed.

Occasionally, contrast material may fill large pseudocysts via fistulous communications. Prolonged emptying of contrast material may be observed.

Common bile duct changes are common in chronic pancreatitis. The most common finding is a long, smooth narrowing of the duct, with gradual tapering of the distal segment due to periductal fibrosis.

In 25% patients with chronic pancreatitis, alternating stenosis and dilation may cause the common bile duct to have an hourglass appearance.

Degree of confidence

The sensitivity of plain abdominal radiography in the detection of pancreatic calcification is approximately 80%, which is higher than that of sonography but lower than that of CT. When seen, pancreatic calcification is pathognomonic for chronic pancreatitis. Barium study findings can be specific for GI tract changes secondary to chronic pancreatitis in the appropriate clinical setting.

ERCP is the most sensitive and specific technique for chronic pancreatitis, although it is invasive and may cause an acute episode of pancreatitis and ascending cholangitis.

False positives/negatives

On anteroposterior radiographs, the spine may mask small punctate calcifications; therefore, the acquisition of additional oblique or lateral images may be indicated. Bowel contents may obscure pancreatic calcification, and calcification in the pancreas and pancreatic bed is not specific for chronic pancreatitis. Causes of pancreatic calcification include acute pancreatitis, cavernous lymphangioma, hemangioma, cystic fibrosis, pancreatic hematoma/infarction, cystadenoma and/or cystadenocarcinoma, islet tumors, metastasis, pseudocysts, and kwashiorkor. Calcification in a vascular atheroma, an aortic aneurysm, or branches of the aorta can occasionally be confused with pancreatic calcification on plain abdominal radiographs.

Gastric displacement seen on barium examination is not specific for chronic pancreatitis and may be due to pancreatic carcinoma, a variety of peripancreatic masses (including adrenal gland or renal masses), aortic aneurysms, exophytic gastric or duodenal tumors, lymphoma and other retroperitoneal tumors, mesenteric cysts, splenic masses, or enlargement of the left lobe of the liver. In some patients, nodular mucosal changes on the medial border of the duodenum may be prominent and may mimic pancreatic carcinoma. Thickened gastric mucosal folds are not specific for chronic pancreatitis; similar thickening can occur with pancreatic carcinoma, lymphoma, gastric carcinoma, gastric sarcoidosis, and Ménétrier disease.

Widening of the duodenal loop is reported as a normal variant, but a similar abnormality is reported with aortic aneurysm; choledochal cysts; duodenal hematoma; retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy; retroperitoneal tumors; parasitic disease; and neoplasms of the stomach, colon, and kidney.

Small-bowel changes in chronic pancreatitis may mimic other causes of intestinal ischemia, Crohn disease, and malabsorption. Colonic changes may mimic vascular ischemia, Crohn disease, and primary colonic carcinoma.

Although ERCP findings can be specific in patients with chronic pancreatitis, they may be confused with those of pancreatic carcinoma in 10% of patients. Such confusion may arise with focal forms of chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma extending through the entire pancreas, and coexisting chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) may have imaging findings identical to those of chronic pancreatitis, such as main duct and side-chain dilatation. ERCP can be used to differentiate main duct IPMN from chronic pancreatitis, because the former often shows mucin bulging from the ampulla.

Computed Tomography

CT features of chronic pancreatitis that can be visualized on CT scans include dilatation of the main pancreatic duct; calcifications; changes in size, shape, and contour; pseudocysts; and bile duct changes. [16, 20, 21]

(See the CT images of chronic pancreatitis below.)

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas.

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas.

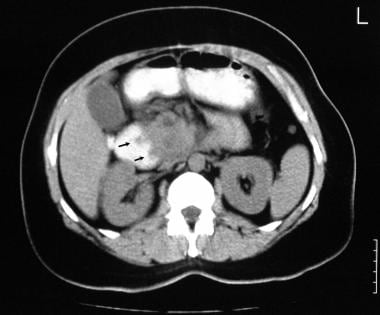

Chronic pancreatitis. Enhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows a low-attenuating mass at the junction of the head and body of the pancreas due to focal chronic noncalcific pancreatitis.

Chronic pancreatitis. Enhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows a low-attenuating mass at the junction of the head and body of the pancreas due to focal chronic noncalcific pancreatitis.

Chronic pancreatitis. Enhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows a mildly dilated pancreatic duct.

Chronic pancreatitis. Enhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows a mildly dilated pancreatic duct.

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas, associated with a 4-cm pseudocyst to the right of the head of the pancreas.

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas, associated with a 4-cm pseudocyst to the right of the head of the pancreas.

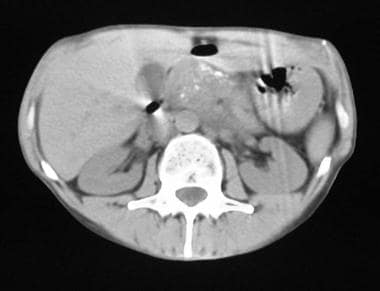

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows a reverse 3 in the Gastrografin-filled duodenum. Note the patchy attenuation in the head of the pancreas. A contrast-enhanced study was not performed because the patient was allergic to intravenous iodinated contrast material.

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows a reverse 3 in the Gastrografin-filled duodenum. Note the patchy attenuation in the head of the pancreas. A contrast-enhanced study was not performed because the patient was allergic to intravenous iodinated contrast material.

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows an enlarged pancreas associated with punctate calcification.

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows an enlarged pancreas associated with punctate calcification.

Main pancreatic duct dilatation can be demonstrated, with the width of the main pancreatic duct exceeding 5 mm in the head and 2 mm in the body and tail. CT is the most sensitive and specific modality for depicting pancreatic calcifications, which may be tiny and punctate or larger and coarse. Focal enlargement or atrophy of the pancreas is readily demonstrated on CT scans. Focal enlargement associated with calcification or ductal dilatation in a mass is suggestive of chronic pancreatitis.

Obliteration of the peripancreatic fat, which results in poor definition and an ill-defined pancreatic contour, is usually seen in acute exacerbations of chronic pancreatitis. Obliteration of the fat sleeve around the superior mesenteric artery has been described in both chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma.

Obstruction of the common bile duct may be visualized as a gradual tapering of the ductal lumen. By contrast, a pancreatic carcinoma usually results in an abrupt transition of the common bile duct. Vascular complications of chronic pancreatitis are best depicted by contrast-enhanced CT scans. In images of pseudoaneurysms, high-attenuation masses are seen during the arterial phase. Portal and/or splenic vein thrombosis and associated collateral venous channels are better delineated during the portal venous phase of contrast enhancement.

Degree of confidence

Currently, CT is regarded as the imaging modality of choice for the initial evaluation of suggested chronic pancreatitis. The diagnostic features of pancreatic enlargement, pancreatic calcifications, pancreatic ductal dilatation, thickening of the peripancreatic fascia, and bile duct involvement are depicted well on CT scans.

CT is more sensitive than plain radiography and ultrasonography in the depiction of pancreatic calcification. Moreover, CT depicts calcification in the pancreas, and confusion with nonpancreatic calcification is less likely. The accuracy of CT is 59-95%; the wide variation is due to the wide discrepancy in the criteria used for diagnosis and in the quality of CT scanners. CT helps in the diagnosis of atrophy of the pancreas, providing better results than ultrasonography.

Pancreatic pseudocysts and complications associated with pseudocysts, including various organ involvements, infection, hemorrhage with pseudoaneurysm formation, rupture with fistula formation, and gastrointestinal or biliary obstruction, are well depicted on CT. Detection of these complications are important, as they may necessitate prompt intervention or surgery. [20, 22]

False positives/negatives

Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma share many CT features, and occasionally, differentiation may be impossible. Obliteration of the fat sleeve around the superior mesenteric artery has been described in both chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma.

Pseudotumoral enlargement around focal pancreatitis with extensive fibrous tissue proliferation usually fails to enhance after the administration of contrast material. This characteristic makes the differential diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma difficult.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

In most patients, a normal pancreatic duct is seen on images obtained with T2-weighted short-tau inversion recovery MRI sequences and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). MRCP may depict the characteristic beaded appearance of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic duct calculi are depicted as round filling defects. In chronic pancreatitis, fat-suppressed T1-weighted images usually show a loss of signal intensity. This loss is explained by the fact that pancreatic fibrosis decreases the proteinaceous fluid content of the pancreas, resulting in loss of pancreatic signal intensity. Fibrosis is associated with decreased vascularity, which causes decreased pancreatic gadolinium enhancement. [14, 15]

(See the magnetic resonance images of chronic pancreatitis below.)

Chronic pancreatitis. Transaxial T2-weighted MRI scan through the tail of the pancreas shows a dilated tortuous pancreatic duct (arrow).

Chronic pancreatitis. Transaxial T2-weighted MRI scan through the tail of the pancreas shows a dilated tortuous pancreatic duct (arrow).

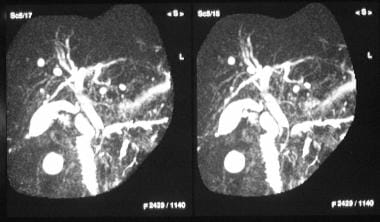

Chronic pancreatitis. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram obtained 24 hours after the placement of a common bile duct stent shows good biliary drainage through the stent. Note the dilated tortuous pancreatic stricture and a downstream stricture in the head of the pancreas (left).

Chronic pancreatitis. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram obtained 24 hours after the placement of a common bile duct stent shows good biliary drainage through the stent. Note the dilated tortuous pancreatic stricture and a downstream stricture in the head of the pancreas (left).

Small punctate pancreatic calcification is difficult to detect by using MRI, but larger calcifications may be seen as foci of a signal void. As a result of its ability to depict fluid, T2-weighted MRI may demonstrate pancreatic and common bile duct irregularities and pseudocysts associated with chronic pancreatitis.

Parenchymal gadolinium enhancement is a useful technique in evaluating focal areas of inflammation. Compared with normal pancreatic segments, inflamed areas have decreased enhancement in the arterial phase and increased enhancement in the equilibrium phase.

Currently, the diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis is difficult. With future improvement in spatial resolution and with the use of secretin-enhanced pancreatography, the detection of subtle changes of the side branches may allow the earlier noninvasive diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Secretin-enhanced pancreatography also has the potential to depict the anatomic relationships of pancreatic ducts and pseudocysts and to aid in the evaluation of pancreatic exocrine function.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness.

Degree of confidence

Because of the introduction of faster imaging sequences and phased-array coils, the accuracy of MRCP has improved considerably, although some concern remains regarding the resolution of smaller pancreatic ducts.

Secretin-enhanced MRCP improves the detection of diseased pancreatic ducts when no abnormality can be shown in physiologic conditions. It also provides additional functional information regarding pancreatic exocrine function. As experience grows, MRI imaging, particularly MRCP, may be increasingly used in assessing and screening for chronic pancreatitis.

Standard good-quality protocols are important with MRCP; otherwise, poor examination technique may create false lesions, which may increase the frequency of unnecessary ERCP examinations.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography may be useful in depicting the anatomy of the pancreas. Primary findings on abdominal ultrasonography include changes in the size, shape contour, and echotexture of the pancreas (see the images below). Irregular pancreatic contour is seen in 45-60% of patients, focal enlargement is detected in 12-32%, and diffuse enlargement occurs in 27-45%. Peripancreatic fascial thickening and blurring of the pancreatic margins are seen in approximately 15% of patients. [8, 23, 24, 25]

Chronic pancreatitis. Transverse sonogram shows an echogenic, enlarged pancreas with multiple small hyperechoic nonshadowing foci in the pancreas.

Chronic pancreatitis. Transverse sonogram shows an echogenic, enlarged pancreas with multiple small hyperechoic nonshadowing foci in the pancreas.

Chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal sonogram through the head of the pancreas (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows an echogenic pancreas with multiple, small, hyperechoic, nonshadowing foci.

Chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal sonogram through the head of the pancreas (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows an echogenic pancreas with multiple, small, hyperechoic, nonshadowing foci.

Chronic pancreatitis. A 52-year-old woman known to have chronic pancreatitis presented with moderate left upper quadrant pain. Transverse sonogram through the pancreas shows a 4.37-cm pseudocyst in the tail of the pancreas (arrow).

Chronic pancreatitis. A 52-year-old woman known to have chronic pancreatitis presented with moderate left upper quadrant pain. Transverse sonogram through the pancreas shows a 4.37-cm pseudocyst in the tail of the pancreas (arrow).

Chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal sonogram (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows a pseudocyst at the splenic hilum. Doppler sonogram (not shown) showed no signal in the splenic vein.

Chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal sonogram (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows a pseudocyst at the splenic hilum. Doppler sonogram (not shown) showed no signal in the splenic vein.

Ultrasonography is the first modality to be used in patients presenting with upper abdominal pain, although the direct diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is not always possible. Sonography can help in determining the cause of chronic pancreatitis (eg, alcoholic liver disease, calculus disease) and in assessing the complications of the disease (eg, pseudocysts, ascites, splenic/portal venous obstruction). [8]

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an important imaging modality to detect early morphologic changes in CP. It can detect mild parenchymal and ductal changes not seen on CT scan, and can be used when CT and MR imaging are non-diagnostic. The most predictive endosonographic feature of chronic pancreatitis is the presence of stones. [2]

The Rosemont classification system is designed to standardize the endosonographic assessment of CP and categorize patients undergoing endosonography by the likelihood of having CP on the basis of particular EUS criteria. Major criteria include hyperechoic foci with shadowing and main pancreatic duct calculi, and lobularity with honeycombing. Minor criteria include cysts, dilated ducts ≥3.5 mm, irregular pancreatic duct contour, dilated side branches ≥1 mm, hyperechoic duct wall, strands, nonshadowing hyperechoic foci, and lobularity with noncontiguous lobules. However, these criteria for predicting prognosis and outcome of therapy in patients with chronic pancreatitis is unknown. [9, 10]

In early disease, the pancreas may be enlarged and hypoechoic, with ductal dilatation. Later, the pancreas becomes heterogeneous, with areas of increased echogenicity and focal or diffuse enlargement. Pseudocysts may occur, and focal hypoechoic inflammatory masses may mimic pancreatic neoplasia. Calculi and calcification in the gland result in densely echogenic foci, which may show shadow. The pancreatic and common bile ducts may be dilated.

In late stages of the disease, the pancreas becomes atrophic and fibrotic, and it shrinks. These changes result in a small, echogenic pancreas with a heterogeneous echotexture. The pancreatic duct remains dilated and has a beaded appearance because of multiple stenoses. When seen, biliary dilation is mild.

Other complications, such as arterial pseudoaneurysms, left-sided portal hypertension (ie, splenic venous thrombosis), and pleural effusions are readily detected by using sonography.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)

EUS is more sensitive at showing the changes mentioned above, and the changes can be seen at an earlier stage of disease. There are nine criteria used in diagnosing CP with EUS: four parenchymal features including hyperechoic foci, hyperechoic strands, lobular contour, and cysts, and five ductal features including main duct dilatation, duct irregularity, hyperechoic margins, visible side branches, and stones. Currently there is no firmly established number of criteria needed to diagnose CP, but the sensitivity and specificity increases with increasing number of criteria. [2]

Degree of confidence

Although ultrasonography cannot always help in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, it is a highly accurate noninvasive technique for detecting the complications of chronic pancreatitis. Ultrasonography also can help in detecting other causes of epigastric pain.

Sonograms may demonstrate a normal pancreas in the presence of established chronic pancreatitis. The pancreas is not always seen; it may be obscured by gas or fat. Differentiation between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma may be difficult and sometimes impossible.

Nuclear Imaging

FDG-PET to detection pancreatic carcinoma in chronic pancreatitis

Patients with chronic pancreatitis are at risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has been established as a tool for the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Early detection is mandatory, as cure can only be achieved in nonadvanced disease; however, this is very difficult with conventional radiologic techniques.

Van Kouwen et al investigated whether FDG-PET can detect pancreatic cancer in the setting of chronic pancreatitis, [26] and they found that in 67 of the 77 patients with chronic pancreatitis (87%), pancreatic FDG accumulation was absent. Of the 6 patients with pancreatic cancer complicating chronic pancreatitis, focal uptake was seen in 5 patients and minor uptake in 1 patient. FDG-PET was positive in almost all pancreatic cancer patients (used as controls). FDG-PET was negative in the large majority (87%) of patients, which suggests that a positive PET scan in chronic pancreatitis patients must lead to efforts to exclude a malignancy.

These data suggest that FDG-PET has a potential role as a diagnostic tool for detecting pancreatic cancer in long-standing chronic pancreatitis. Rasmussen and associates, however, could not confirm or exclude malignancy in 25 indeterminate pancreatic head masses using FDG-PET imaging. 11C-acetate-PET provided no additional diagnostic benefits. [27]

FDG-PET of AIP

PET is more sensitive than conventional imaging to detect organ involvement and uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose in organs other than the pancreas often suggests AIP when the clinical characteristic, histology, and serum detection incline the diagnosis of IgG4 related disease. [7]

Degree of confidence

In studies noted above, [26, 27] FDG-PET was positive in almost all pancreatic cancer patients (used as controls) and cancer complicating chronic pancreatitis. FDG-PET was negative in the large majority (87%) of chronic pancreatitis patients, which suggests that a positive PET scan in chronic pancreatitis patients must lead to efforts to exclude a malignancy.

Angiography

Angiographic findings in pancreatitis are related to the duration and severity of disease. Vascular abnormalities are usually minimal in patients who have had the disease for less than 2 years. The tortuosity of the pancreatic vessels is increased and associated with angulation of the pancreatic arcades.

(See the angiographic images of chronic pancreatitis below.)

Chronic pancreatitis. Manually subtracted celiac-axis angiogram shows stretching of the pancreaticoduodenal artery with arterial tortuosity and a capillary blush in the region of the splenic hilum. These findings are superimposed on the left kidney and suggest an inflammatory mass.

Chronic pancreatitis. Manually subtracted celiac-axis angiogram shows stretching of the pancreaticoduodenal artery with arterial tortuosity and a capillary blush in the region of the splenic hilum. These findings are superimposed on the left kidney and suggest an inflammatory mass.

Chronic pancreatitis. Manually subtracted venous-phase celiac-axis angiogram (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows an occluded splenic vein and a large peripancreatic collateral vein that drains into the portal vein.

Chronic pancreatitis. Manually subtracted venous-phase celiac-axis angiogram (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows an occluded splenic vein and a large peripancreatic collateral vein that drains into the portal vein.

In long-standing disease, the major intrapancreatic arteries and their branches have a beaded appearance in which short dilated segments alternate with narrow segments. Long-standing chronic pancreatitis associated with patch fibrosis results in the prolonged accumulation of contrast material. With diffuse fibrosis, both the number of intrahepatic arteries and the contrast agent accumulation are decreased.

The major vessels around the pancreas may be involved. The splenic artery is particularly susceptible to pancreatitis, and a sleevelike narrowing of the artery may occur. The splenic and superior mesenteric veins may be narrowed or may have luminal irregularities. Venous compression and/or occlusion, particularly in the splenic vein, occurs in 20-50% of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Portoportal shunting and gastric varices without esophageal varices may be seen as a result of splenic vein occlusion.

Degree of confidence

Pancreatic angiography is usually reserved for patients in whom vascular complications from chronic pancreatitis are suspected. Angiography aids in the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysms, which may be treated by means of transcatheter embolization. By using certain criteria, differentiation between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma is possible in some patients on the basis of angiography.

The sleevelike narrowing of the splenic artery that occurs in pancreatitis may appear similar to atherosclerosis. However, the splenic artery is straight and narrow in pancreatitis, whereas, in atherosclerosis, it tends to be generally tortuous and irregularly narrowed. Encasement by a carcinoma may cause a similar sleevelike narrowing, but the involved segment is usually short.

Occasionally, differentiation between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma can be difficult with angiography; unfortunately, this also is the case with nearly all available imaging modalities.

The major differentiating features include the following:

-

The course of the pancreatic arteries remains relatively unchanged in chronic pancreatitis. In contrast, a pancreatic carcinoma invariably changes the course of the arteries, which is characterized by abrupt angulation and distortion. However, similar changes may occur in chronic pancreatitis when pancreatic fibrosis ensues.

-

Changes in arterial luminal caliber in chronic pancreatitis remain relatively smooth. In contrast, a carcinoma results in irregular and jagged-appearing changes in the caliber of the lumen.

-

Characteristic arterial changes in chronic pancreatitis tend to be associated with an increase in the number of arteries, whereas, in carcinoma, the overall vascularity is decreased.

-

Vascular changes in chronic pancreatitis are more diffuse, and carcinomas usually cause focal changes.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows coarse calcification in the distribution of the pancreas due to chronic calcific pancreatitis.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows calcification in the pancreas associated with osteomalacia secondary to malabsorption. Note the pseudofracture in the right 11th rib (arrow).

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Upper gastrointestinal tract barium study shows a reverse 3 in the duodenum due to chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic carcinoma can have a similar appearance.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Enhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows a low-attenuating mass at the junction of the head and body of the pancreas due to focal chronic noncalcific pancreatitis.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Enhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows a mildly dilated pancreatic duct.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows granular calcification in the pancreas, associated with a 4-cm pseudocyst to the right of the head of the pancreas.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows a reverse 3 in the Gastrografin-filled duodenum. Note the patchy attenuation in the head of the pancreas. A contrast-enhanced study was not performed because the patient was allergic to intravenous iodinated contrast material.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Transaxial T2-weighted MRI scan through the tail of the pancreas shows a dilated tortuous pancreatic duct (arrow).

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram shows a dilated common bile duct (CBD) associated with a stricture of the lower CBD (not well shown on this image) and a dilated ectatic tortuous pancreatic duct. A stent was subsequently placed across the CBD stricture.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram obtained 24 hours after the placement of a common bile duct stent shows good biliary drainage through the stent. Note the dilated tortuous pancreatic stricture and a downstream stricture in the head of the pancreas (left).

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Plain abdominal radiograph shows a common bile duct stent in situ and fairly extensive pancreatic calcification.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Transverse sonogram shows an echogenic, enlarged pancreas with multiple small hyperechoic nonshadowing foci in the pancreas.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal sonogram through the head of the pancreas (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows an echogenic pancreas with multiple, small, hyperechoic, nonshadowing foci.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Nonenhanced axial CT scan through the pancreas shows an enlarged pancreas associated with punctate calcification.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. A 52-year-old woman known to have chronic pancreatitis presented with moderate left upper quadrant pain. Transverse sonogram through the pancreas shows a 4.37-cm pseudocyst in the tail of the pancreas (arrow).

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal sonogram (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows a pseudocyst at the splenic hilum. Doppler sonogram (not shown) showed no signal in the splenic vein.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Manually subtracted celiac-axis angiogram shows stretching of the pancreaticoduodenal artery with arterial tortuosity and a capillary blush in the region of the splenic hilum. These findings are superimposed on the left kidney and suggest an inflammatory mass.

-

Chronic pancreatitis. Manually subtracted venous-phase celiac-axis angiogram (in the same patient as in the previous image) shows an occluded splenic vein and a large peripancreatic collateral vein that drains into the portal vein.