Practice Essentials

Mesenteric ischemia is characterized by inadequate blood flow to or from the involved mesenteric vessels supplying a particular segment of bowel (see the images below). The organs typically affected are the small bowel or colon. The source of blood that is lacking can be arterial or venous, and hemodynamically, the cause can be occlusive or nonocclusive. Mesenteric ischemia can be acute or chronic. [1] Most cases of mesenteric ischemia are due to an acute event leading to decreased blood supply to the splanchnic vasculature. Chronic mesenteric ischemia is uncommon, accounting for less than 5% of cases of mesenteric ischemia, and is almost always associated with diffuse atherosclerotic disease. [2]

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) may be classified as either arterial or venous. AMI as arterial disease may be subdivided into nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) and occlusive mesenteric arterial ischemia (OMAI); OMAI may be further subdivided into acute mesenteric arterial embolism (AMAE) and acute mesenteric arterial thrombosis (AMAT). AMI as venous disease takes the form of mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT). Thus, for practical purposes, AMI comprises 4 different primary clinical entities: NOMI, AMAE, AMAT, and MVT.

The 4 types of AMI have somewhat different predisposing factors, clinical pictures, and prognoses. A secondary clinical entity of mesenteric ischemia occurs as a consequence of mechanical obstruction (eg, from internal hernia with strangulation, volvulus, or intussusception). Tumor compression, aortic dissection, and postangiography thrombosis are other reported causes. Occasionally, blunt trauma may cause isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and lead to intestinal infarction.

AMI is a vascular emergency that will lead to death if left untreated. Although the disease is responsible for fewer than 1 in 1,000 hospital admissions, mortality remains high, ranging frin 30 to 90% in acute settings despite advances in treatment options. Higher prevalence in the elderly population and nonspecific clinical presentation leading to delayed diagnosis contribute to the high mortality. [2]

(See the images below.)

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements shows thumbprinting of the transverse colon. Differential diagnosis included inflammatory/infectious versus ischemic disease. A CT scan was obtained (see the next image).

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements shows thumbprinting of the transverse colon. Differential diagnosis included inflammatory/infectious versus ischemic disease. A CT scan was obtained (see the next image).

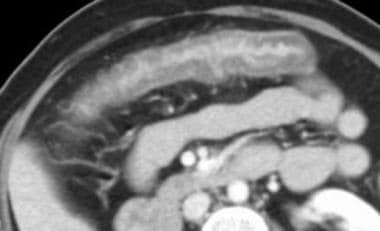

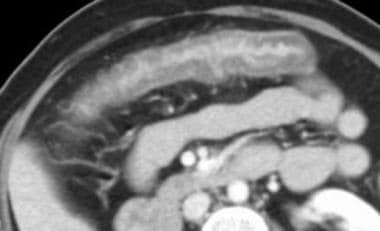

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements (same patient as in the previous image) shows thickening of the transverse colon, which is correlated with the plain radiographic findings. These findings suggest a distribution in the superior mesenteric artery territory.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements (same patient as in the previous image) shows thickening of the transverse colon, which is correlated with the plain radiographic findings. These findings suggest a distribution in the superior mesenteric artery territory.

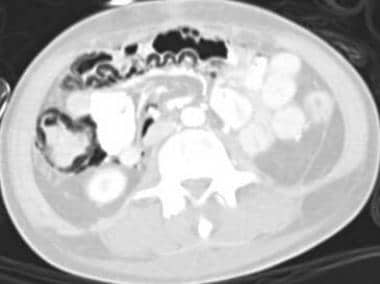

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 72-year-old man with bright-red blood per rectum and abdominal pain shows thickening of the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. The differential diagnoses included conditions with an infectious etiology versus ischemia. Magnetic resonance angiography was performed, and images showed stenosis at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 72-year-old man with bright-red blood per rectum and abdominal pain shows thickening of the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. The differential diagnoses included conditions with an infectious etiology versus ischemia. Magnetic resonance angiography was performed, and images showed stenosis at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery.

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals pneumatosis of the colon dissecting the bowel wall. CT scan revealed the extent of pneumatosis (see the next image).

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals pneumatosis of the colon dissecting the bowel wall. CT scan revealed the extent of pneumatosis (see the next image).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan obtained by using lung window parameters in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals free retroperitoneal air (same patient as in the previous image).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan obtained by using lung window parameters in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals free retroperitoneal air (same patient as in the previous image).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis shows the true extent of the pneumatosis with curvilinear air collections in the colonic wall (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Note how the use of lung windows for abdominal CT makes the intramural air more detectable.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis shows the true extent of the pneumatosis with curvilinear air collections in the colonic wall (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Note how the use of lung windows for abdominal CT makes the intramural air more detectable.

The diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia often is a challenge to both clinicians and radiologists. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease and infectious colitis can present with similar physical signs and symptoms, including cramping abdominal pain, diarrhea, leukocytosis, and hematochezia. Bowel wall thickening is a finding common to all 3 types of disease; however, the pattern of vascular distribution can sometimes narrow the differential diagnosis.

Guidelines

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria for imaging of mesenteric ischemia are summarized as follows [2] :

-

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast has been shown to provide best accuracy and inter-reader agreement for grading mesenteric vessel stenosis compared to magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and ultrasonography.

-

CTA of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast is the recommended initial imaging study for evaluation of suspected AMI.

-

CTA of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast or MRA without and with IV contrast is the recommended initial imaging study for evaluation of suspected chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI)

The 2017 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Siociety for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases includes the following recommendations for the diagnosis of mesenteric artery disease [3] :

-

Urgent CTA should be performed in patients with suspected AMI.

-

For evaluation of suspected CMI, duplex ultrasound should be the first-line study performed.

Guidelines from the World Society of Emergency Surgery concur with the recommendation to perform CTA as soon as possible for any patient with suspicion for AMI. The guidelines also note that although radiographs are usually the initial test ordered in patients with acute abdominal pain, they have a limited role in the diagnosis of AMI. A negative radiograph does not exclude mesenteric ischemia. Plain radiography only becomes positive when bowel infarction has developed and intestinal perforation manifests as free intraperitoneal air. [4]

The European Society for Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) guidelines for diagnosis and management of AMI recommend biphasic multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with intravenous contrast as the first-line imaging in suspected AMI due to its high diagnostic accuracy and its ability to exclude other causes of acute abdominal pain. [5]

Preferred examination

Pertinent history and a physical examination can narrow the differential diagnosis in patients with an acute abdomen, particularly when considering the timing of the event, localizing signs and symptoms, and vascular distribution of the pain. The diagnostic work-up of AMI requires a noninvasive test that confirms the diagnosis and differentiates it from other abdominal pathology. Any delay of the initial diagnosis and intestinal revascularization increases the mortality risk. The lethality of AMI rises exponentially from 10% to 100% within 24 hours. [6]

Upright and supine plain abdominal radiographs typically are requested first to evaluate for free air, obstruction, ileus, intussusception, or volvulus. A CT scan using oral and, preferably, intravenous contrast material follows if the cause is not apparent on plain radiographs. [7, 8, 9]

When an AMI is suspected, biphasic CTA is the diagnostic method of choice and should be performed without delay. The method is universally available, is time-saving, and has a high diagnostic value for all intra-abdominal pathologies. Sensitivity is 93% and specificity is 100%, while the positive and negative prognostic values are 94% and 100%, respectively. A CT scan immediately enables many treatment options of both abdominal and vascular pathologies, with the additional option of an endovascular intervention. If colorectal ischemia is suspected, endoscopic evaluation of the colorectal mucosa should be promptly performed. Other diagnostic means (eg, abdominal ultrasound, abdominal radiograph, catheter angiography, or magnetic resonance tomography) are usually time-consuming and do not offer a comprehensive presentation of all abdominal organs. [6]

Limitations of techniques

Plain abdominal radiographs are helpful initial screening tools for excluding certain manifestations of disease. Although plain radiographs may be sensitive, they are typically nonspecific. For instance, the presence of mucosal edema, small-bowel dilatation, and free air on plain radiographs are sensitive findings; however, these findings are not useful in localizing or determining the etiology of the event.

CT scans are more specific regarding the cause of the findings, and CT scans may occasionally reveal additional findings, such as the presence of portal venous gas, which may be missed on plain radiographs.

Nonenhanced CT scans have an inherent limitation: CT scans obtained without oral contrast enhancement are not helpful in differentiating mucosal thickening from nonopacified bowel loops. Although CT findings may help localize a diseased segment of bowel, differentiating a venous origin from an arterial origin in thrombosis often is difficult, even with the proper intravenous administration of contrast material. In addition, differentiating ischemic colitis from infectious colitis can often be difficult using CT scans.

The presence of overlying bowel gas, obesity, and vascular calcifications are challenges for an adequate sonographic evaluation. In addition, duplex ultrasonography has a limited role in detecting distal arterial emboli or in diagnosing nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia. Moreover, the length of the examination and the possible pain associated with the applied pressure to the abdomen during imaging may be limiting factors in initial evaluation of patients with suspected acute mesenteric ischemia. [2]

Radiography

Plain radiographic findings are often normal. Although upright and supine abdominal images are helpful screening tools for detecting free air or bowel obstruction, the findings are usually not specific for mesenteric ischemia. Findings such as thumbprinting (mucosal edema) are occasionally masked by a gasless fluid-filled abdomen. Mesenteric ischemia is rarely, if ever, diagnosed by using plain abdominal images. Because the disease is a continuum, normal findings on abdominal radiographs should not mislead the interpreter to exclude the disease. The diagnosis often requires the use of additional imaging modalities.

With barium enema examination, a decreased and irregular bowel lumen is seen. When free air, bowel obstruction, or thumbprinting is apparent, plain radiographic findings are often sensitive but not specific for the disease because many other forms of bowel disease can exhibit similar findings. Another plain radiographic finding is pneumatosis, which represents luminal gas that has dissected into the bowel wall and is seen in less than 30% of patients. Peripherally located portal venous gas in the right or left upper quadrant is a rare finding on plain radiographs that strongly suggests mesenteric ischemia. Other causes of colonic or small-bowel-wall thickening include ulcerative colitis and lymphoma infiltration.

(See the images below.)

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements shows thumbprinting of the transverse colon. Differential diagnosis included inflammatory/infectious versus ischemic disease. A CT scan was obtained (see the next image).

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements shows thumbprinting of the transverse colon. Differential diagnosis included inflammatory/infectious versus ischemic disease. A CT scan was obtained (see the next image).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements (same patient as in the previous image) shows thickening of the transverse colon, which is correlated with the plain radiographic findings. These findings suggest a distribution in the superior mesenteric artery territory.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements (same patient as in the previous image) shows thickening of the transverse colon, which is correlated with the plain radiographic findings. These findings suggest a distribution in the superior mesenteric artery territory.

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals pneumatosis of the colon dissecting the bowel wall. CT scan revealed the extent of pneumatosis (see the next image).

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals pneumatosis of the colon dissecting the bowel wall. CT scan revealed the extent of pneumatosis (see the next image).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan obtained by using lung window parameters in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals free retroperitoneal air (same patient as in the previous image).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan obtained by using lung window parameters in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals free retroperitoneal air (same patient as in the previous image).

Computed Tomography

CT is the primary imaging modality (see the images below), and it has been proven to be highly accurate in the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia; scans sometimes depict the underlying etiology. Typically, CT scans show mesenteric edema with irregular thickening of the wall of the small or large bowel that is greater than 3 mm. Large-vessel disease (superior mesenteric artery/vein [SMA/SMV]; inferior mesenteric artery/vein [IMA/IMV]) is diffuse, whereas small-vessel arterial or venous disease is more likely to be focal. [7, 8, 10, 11, 12]

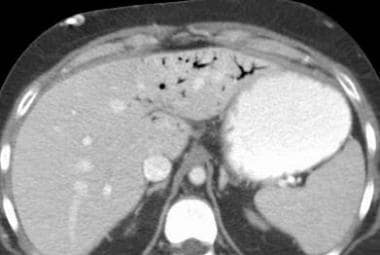

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 72-year-old man with bright-red blood per rectum and abdominal pain shows thickening of the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. The differential diagnoses included conditions with an infectious etiology versus ischemia. Magnetic resonance angiography was performed, and images showed stenosis at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 72-year-old man with bright-red blood per rectum and abdominal pain shows thickening of the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. The differential diagnoses included conditions with an infectious etiology versus ischemia. Magnetic resonance angiography was performed, and images showed stenosis at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 56-year-old woman with abdominal pain and a family history of colon cancer shows inflammatory changes and thickening of the hepatic flexure, initially believed to represent cancer. Colonoscopy with biopsy showed focal mucosal necrosis with ulceration consistent with ischemic colitis, which likely is caused by a small contributing vessel, since it is only seen focally at the hepatic flexure.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 56-year-old woman with abdominal pain and a family history of colon cancer shows inflammatory changes and thickening of the hepatic flexure, initially believed to represent cancer. Colonoscopy with biopsy showed focal mucosal necrosis with ulceration consistent with ischemic colitis, which likely is caused by a small contributing vessel, since it is only seen focally at the hepatic flexure.

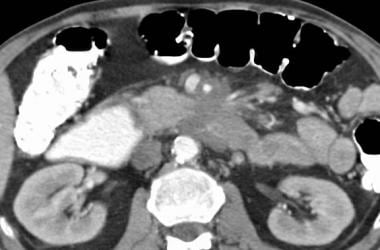

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis shows congested, edematous, central small bowel loops. Thrombosis was found in the superior mesenteric vein (also see the 2 Images that follow).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis shows congested, edematous, central small bowel loops. Thrombosis was found in the superior mesenteric vein (also see the 2 Images that follow).

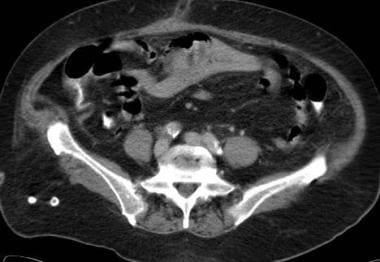

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis reveals a hypoattenuating thrombus in an enhanced superior mesenteric vein, revealing a venous source of the small bowel ischemia (same patient as in the Image above and the Image below). A resultant cavernous transformation is seen in the Image below.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis reveals a hypoattenuating thrombus in an enhanced superior mesenteric vein, revealing a venous source of the small bowel ischemia (same patient as in the Image above and the Image below). A resultant cavernous transformation is seen in the Image below.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis shows cavernous transformation of the portal vein with abundant collateral vessels, causing venous congestion of the small bowel mesentery. This is likely secondary to thrombus in the portal vein (same patient as in the 2 Images above).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis shows cavernous transformation of the portal vein with abundant collateral vessels, causing venous congestion of the small bowel mesentery. This is likely secondary to thrombus in the portal vein (same patient as in the 2 Images above).

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 36-year-old woman with abdominal pain and guaiac-positive stool from her colostomy shows portal-venous air in the left hepatic lobe. Pneumatosis of the small bowel was present, consistent with small bowel infarction.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 36-year-old woman with abdominal pain and guaiac-positive stool from her colostomy shows portal-venous air in the left hepatic lobe. Pneumatosis of the small bowel was present, consistent with small bowel infarction.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 59-year-old man with pancreatic adenocarcinoma shows a large mass encasing the superior mesenteric artery. The patient did not have abdominal symptoms of ischemia because the superior mesenteric artery remained patent. Tumor encasement is a rare cause of mesenteric ischemia.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 59-year-old man with pancreatic adenocarcinoma shows a large mass encasing the superior mesenteric artery. The patient did not have abdominal symptoms of ischemia because the superior mesenteric artery remained patent. Tumor encasement is a rare cause of mesenteric ischemia.

With proper timing of the contrast-agent bolus, a thrombus in a large vessel is seen as a soft-tissue filling defect in rare cases. Small-bowel obstruction can cause vessel obstruction and lead to ischemia, which often is apparent as dilated loops on CT scans.

With mucosal disruption and gas dissection, intramural air can be seen. This is often best appreciated by using lung window settings. This entity is called pneumatosis intestinalis.

Gas may enter the portal circulation, and it may be found in peripherally located portal vein branches, usually in the nondependent left hepatic lobe.

A reliable method to differentiate arterial causes from venous causes is depiction of the characteristic bowel-wall enhancement pattern. Arterial occlusive disease demonstrates no enhancement of the involved segment, whereas venous occlusion reveals marked contrast enhancement and retention secondary to stagnant flow.

Regardless of the cause, mesenteric ischemia produces findings that may mimic those of other inflammatory or infectious conditions. Wall thickening is the most common sign; however, the vascular territory of involvement is not always clear. This limitation reduces the interpreter's degree of confidence regarding the exact etiology. In addition, ischemic colitis can involve both the SMA and IMA in rare cases, producing wall thickening of the left and right colon.

The presence of ulcerative colitis can lead to a false-positive diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia, particularly if the sigmoid and descending segments of the colon are involved. This type of ulcerative colitis simulates ischemia caused by IMA occlusion. Ulcerative colitis involves the rectum in more than 90% of patients because the process progresses in a retrograde fashion. However, in ischemic colitis, the rectum is spared.

A false-negative diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia can result from many causes. Focal wall thickening, particularly of the cecum, can be confusing. Tumor infiltration, especially that caused by lymphoma and adenocarcinoma, can mimic focal ischemic colitis caused by small colic branches of the SMA. Local lymph node enlargement may be present in infectious and neoplastic processes, allowing them to be further differentiated from ischemia.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography with B-mode and Doppler waveform analysis is a useful initial screening tool for chronic mesenteric ischemia. Duplex is best performed in the fasting state and early in the day to avoid bowel gas, as visualizing the mesenteric vessels with duplex US can be technically challenging. [2]

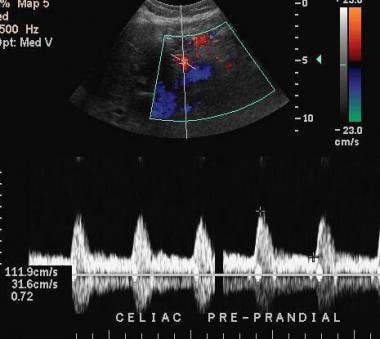

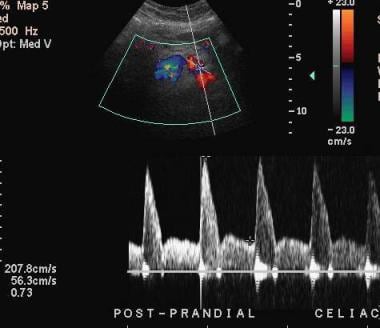

Color Doppler and spectral waveform ultrasonography help evaluate the patency and adequacy of flow through the celiac artery, SMA, and IMA (see the images below). Sample velocities are assessed proximal to the stenosis, where flow is expected to be normal; at the stenosis, where velocity is maximal; and distal to the stenosis, where velocity is the most turbulent. [13]

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation with spectral analysis and color Doppler imaging in a 64-year-old man shows a typical normal pattern.

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation with spectral analysis and color Doppler imaging in a 64-year-old man shows a typical normal pattern.

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation with spectral analysis and color Doppler imaging in a 64-year-old man shows a typical normal pattern of response. The normal postprandial response of the celiac artery shown here is an increase in the peak systolic velocity, suggesting patency of flow. An abnormal response would be a blunted increase in the peak systolic velocity in response to eating, indicating stenosis.

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation with spectral analysis and color Doppler imaging in a 64-year-old man shows a typical normal pattern of response. The normal postprandial response of the celiac artery shown here is an increase in the peak systolic velocity, suggesting patency of flow. An abnormal response would be a blunted increase in the peak systolic velocity in response to eating, indicating stenosis.

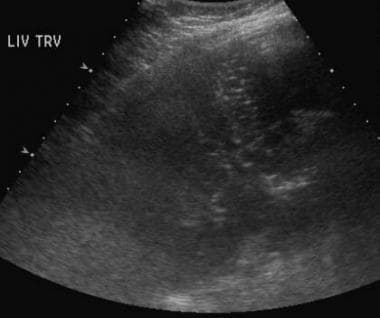

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation in an 83-year-old woman with abdominal pain reveals multiple echogenic foci within the liver, which are suggestive of portal venous air. CT scans confirmed the finding and revealed the cause (see the next 2 images).

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation in an 83-year-old woman with abdominal pain reveals multiple echogenic foci within the liver, which are suggestive of portal venous air. CT scans confirmed the finding and revealed the cause (see the next 2 images).

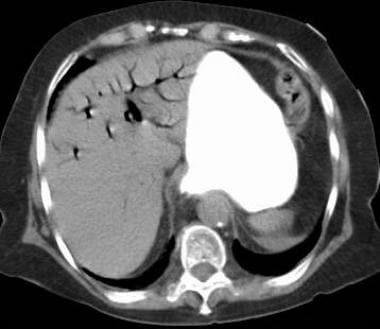

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in an 83-year-old woman (same patient as in the previous image) obtained after suggestive sonographic findings of portal venous air were observed confirms the presence of air in the portal-venous system and proximal small bowel mucosal edema. These findings suggest ischemia of the affected bowel.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in an 83-year-old woman (same patient as in the previous image) obtained after suggestive sonographic findings of portal venous air were observed confirms the presence of air in the portal-venous system and proximal small bowel mucosal edema. These findings suggest ischemia of the affected bowel.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in an 83-year-old woman (same patient as in the previous 2 images) obtained after suggestive sonographic findings of portal venous air were observed confirms the presence of air in the portal-venous system and proximal small-bowel mucosal edema. These findings suggest ischemia of the affected bowel. Whenever pneumatosis is found, one should search the mesenteric and portal veins for gas.

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in an 83-year-old woman (same patient as in the previous 2 images) obtained after suggestive sonographic findings of portal venous air were observed confirms the presence of air in the portal-venous system and proximal small-bowel mucosal edema. These findings suggest ischemia of the affected bowel. Whenever pneumatosis is found, one should search the mesenteric and portal veins for gas.

The normal response to a meal is an increase in blood flow through the mesenteric circulation, which is measured as the peak systolic arterial flow. Stenosis or occlusion decreases normal laminar blood flow. The severity of the stenosis in the sampled artery is best correlated with the maximum peak systolic velocity.

A luminal stenosis greater than 60-70% is usually considered severe. In response to eating, the peak systolic velocity should increase as arterioles dilate to supply the bowel segment. Published reports of highly predictive values of stenosis include a fasting peak systolic velocity of more than 275 cm/s in the SMA or 200 cm/s in the celiac artery. The normal postprandial peak systolic velocity should increase by approximately 20% or more. An abnormal postprandial response is interpreted as an increase in the peak systolic velocity of less than 20%, which is a blunted response.

Another useful parameter is the end-diastolic velocity of the sampled artery during the compliant diastolic cardiac state. The normal end diastolic velocity should increase in the postprandial state, since compliance is greater in this phase of the cardiac and systemic cycle. With stenosis, the end diastolic velocity should decrease secondary to decreased compliance.

US has been shown to be able to demonstrate proximal mesenteric vessel thrombosis via Doppler mode and can be used to detect proximal superior mesenteric and celiac artery stenosis with high sensitivity and specificity of 85 to 90%. US may also reveal focal superior mesenteric or portal venous thrombosis in cases of venous occlusive ischemia. [2]

Sources of error are related to the cause of the ischemia. Abnormal increases in velocity in response to meals are not specific for the diagnosis of ischemia. The findings of significant abnormalities of the celiac artery and SMA on Doppler sonograms do not necessarily indicate mesenteric ischemia. Additionally, Doppler ultrasonography is not useful in evaluating mesenteric ischemia caused by venous abnormalities. Normal findings on an arterial Doppler sonogram in a symptomatic patient do not exclude venous mesenteric ischemia.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements shows thumbprinting of the transverse colon. Differential diagnosis included inflammatory/infectious versus ischemic disease. A CT scan was obtained (see the next image).

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 49-year-old woman with acute bloody bowel movements (same patient as in the previous image) shows thickening of the transverse colon, which is correlated with the plain radiographic findings. These findings suggest a distribution in the superior mesenteric artery territory.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in an 81-year-old man with abdominal pain and diarrhea shows wall thickening of the ascending colon. This finding also can be seen with infectious colitis; however, assay results for Clostridium difficile were negative. The cause is likely atherosclerotic in origin because of the patient's age and because of the partially calcified aorta.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 72-year-old man with bright-red blood per rectum and abdominal pain shows thickening of the ascending colon and hepatic flexure. The differential diagnoses included conditions with an infectious etiology versus ischemia. Magnetic resonance angiography was performed, and images showed stenosis at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 56-year-old woman with abdominal pain and a family history of colon cancer shows inflammatory changes and thickening of the hepatic flexure, initially believed to represent cancer. Colonoscopy with biopsy showed focal mucosal necrosis with ulceration consistent with ischemic colitis, which likely is caused by a small contributing vessel, since it is only seen focally at the hepatic flexure.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals pneumatosis of the colon dissecting the bowel wall. CT scan revealed the extent of pneumatosis (see the next image).

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan obtained by using lung window parameters in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis reveals free retroperitoneal air (same patient as in the previous image).

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 17-year-old male patient with encephalitis shows the true extent of the pneumatosis with curvilinear air collections in the colonic wall (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Note how the use of lung windows for abdominal CT makes the intramural air more detectable.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis shows congested, edematous, central small bowel loops. Thrombosis was found in the superior mesenteric vein (also see the 2 Images that follow).

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis reveals a hypoattenuating thrombus in an enhanced superior mesenteric vein, revealing a venous source of the small bowel ischemia (same patient as in the Image above and the Image below). A resultant cavernous transformation is seen in the Image below.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 76-year-old woman with a 4-day history of abdominal pain and leukocytosis shows cavernous transformation of the portal vein with abundant collateral vessels, causing venous congestion of the small bowel mesentery. This is likely secondary to thrombus in the portal vein (same patient as in the 2 Images above).

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 36-year-old woman with abdominal pain and guaiac-positive stool from her colostomy shows portal-venous air in the left hepatic lobe. Pneumatosis of the small bowel was present, consistent with small bowel infarction.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in a 59-year-old man with pancreatic adenocarcinoma shows a large mass encasing the superior mesenteric artery. The patient did not have abdominal symptoms of ischemia because the superior mesenteric artery remained patent. Tumor encasement is a rare cause of mesenteric ischemia.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation with spectral analysis and color Doppler imaging in a 64-year-old man shows a typical normal pattern.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation with spectral analysis and color Doppler imaging in a 64-year-old man shows a typical normal pattern of response. The normal postprandial response of the celiac artery shown here is an increase in the peak systolic velocity, suggesting patency of flow. An abnormal response would be a blunted increase in the peak systolic velocity in response to eating, indicating stenosis.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. Ultrasonographic evaluation in an 83-year-old woman with abdominal pain reveals multiple echogenic foci within the liver, which are suggestive of portal venous air. CT scans confirmed the finding and revealed the cause (see the next 2 images).

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in an 83-year-old woman (same patient as in the previous image) obtained after suggestive sonographic findings of portal venous air were observed confirms the presence of air in the portal-venous system and proximal small bowel mucosal edema. These findings suggest ischemia of the affected bowel.

-

Mesenteric ischemia. CT scan in an 83-year-old woman (same patient as in the previous 2 images) obtained after suggestive sonographic findings of portal venous air were observed confirms the presence of air in the portal-venous system and proximal small-bowel mucosal edema. These findings suggest ischemia of the affected bowel. Whenever pneumatosis is found, one should search the mesenteric and portal veins for gas.