Practice Essentials

Given its prominent anatomic location, the mandible is one of the most commonly fractured facial bones. Before the invention of the automobile, mandibular fractures were most often caused by assault or other blunt trauma to the jaw. However, vehicular accidents are now responsible for an equal share of the incidence of such injuries. Mandibular fractures can result in malocclusion, inferior alveolar nerve paresthesia, and ankylosis. In patients who have delayed presentation, infection and osteomyelitis may occur. [1, 2, 3] Mandibular fractures can be classified anatomically, by dentition, by muscle group, and by severity. They may also be closed, open, comminuted, displaced, or pathologic. [4]

Radiologic evaluation is a standard component of the workup of a suspected mandibular fracture (see the images below). With computed tomography (CT) scanning—particularly helical CT and panoramic imaging—in addition to the basic mandibular radiographic study, a comprehensive evaluation and subsequent identification of all but the most subtle fractures can be achieved. CT is the current diagnostic tool of choice for the radiographic evaluation and diagnosis of mandible fractures. [5, 3, 6, 7]

MRI is reserved for assessing soft-tissue injuries associated with condylar fractures and can be used as an additional imaging modality once the patient is stable and if clinical suspicion of such injury is high. For example, it can be used to assess for temporomandibular disc disruption or capsular tear, which can occur with high condylar fractures. [4]

Ultrasonography has been demonstrated as a useful imaging modality in detecting mandibular fractures, with a sensitivity of up to 94%, and has the advantages of being fast and relatively inexpensive without the need for ionizing radiation. It can be particularly useful in trauma patients who are too unstable for CT or who are pregnant. However, ultrasound provides limited detail regarding the severity fractures because of limited views and lack of spatial detail. [4] Endoscopic ultrasonography offers an alternative to MRI for evaluating the temperomandibular joint (TMJ) [8] but is usually performed with maxillofacial surgery. [9, 10, 11]

In rare cases, a bone scan may be used to evaluate healing at a fracture plane; plain radiographs may not show evidence of healing because of the slow radiographic appearance of bone repair. Infection and osteomyelitis after a fracture may be evaluated by means of triple-phase technetium-99m (99mTc) bone scanning. Concurrent plain radiography may also show soft-tissue swelling, periosteal thickening, and focal osteopenia.

Patients should be assessed in accordance with the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol, so that potentially life-threatening injuries are recognized and treated promptly. The mechanism of injury should be identified, because knowledge of the cause of injury can be valuable in determining the type of injury. For example, physical altercations are associated with a higher incidence of angle fractures from a lateral blow to the mandible, and motor vehicle accidents are more commonly associated with parasymphyseal, symphyseal, body, and condylar fractures. Careful evaluation of the C-spine is required, as many studies report a 2-10% incidence of C-spine injuries in patients with facial fractures and up to 20% with panfacial fractures. [2]

In a study of pediatric mandibular fractures (patients ≤18 yr), patients 12 years or younger and female patients tended to have condyle fractures caused more commonly by falls, while older patients (13-18 yr) and male patients tended to have angle fractures caused by assault. [12] In a study of facial fractures in the elderly (>64 yr), patients were more likely to have experienced injury from a fall. [13]

In patients with multiple injuries due to an automobile accident, surgeons may not give mandibular fractures the highest priority, but early detection of such fractures is important because early reduction is associated with improved outcomes. Mandibular fractures can be treated by means of open or closed reduction. CT scanning is often required to identify intact bone before fixation with hardware proceeds.

(See the diagrams and images of mandibular fractures below.)

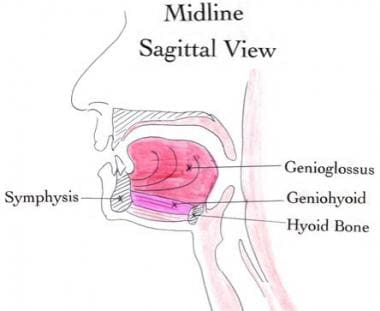

This midline sagittal drawing illustrates the anterior attachments of the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles. If the symphysis becomes a free fragment (as with bilateral parasymphyseal fractures), the symphysis retracts posteriorly, compromising the airway. The anterior belly of the digastric muscle is not depicted in the image because it is lateral to this central section.

This midline sagittal drawing illustrates the anterior attachments of the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles. If the symphysis becomes a free fragment (as with bilateral parasymphyseal fractures), the symphysis retracts posteriorly, compromising the airway. The anterior belly of the digastric muscle is not depicted in the image because it is lateral to this central section.

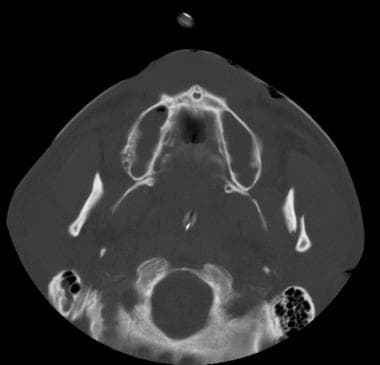

Axial computed tomography scan of a left condylar fracture, with lateral displacement of the proximal condylar fragment.

Axial computed tomography scan of a left condylar fracture, with lateral displacement of the proximal condylar fragment.

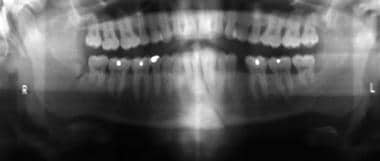

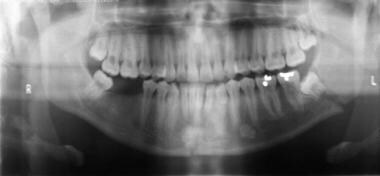

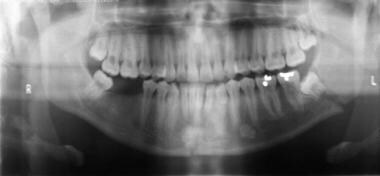

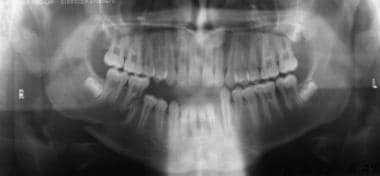

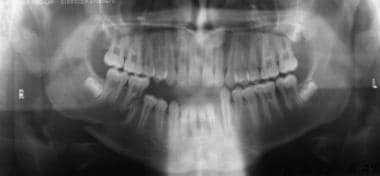

Panoramic radiographic image shows a left angle fracture extending to and dislodging the molar. This image also shows a right symphyseal fracture.

Panoramic radiographic image shows a left angle fracture extending to and dislodging the molar. This image also shows a right symphyseal fracture.

Delayed union, nonunion, and malunion are of concern in evaluating the response of mandibular fractures to treatment. Delayed union is the absence or delay of healing at the fracture plane along its normal timetable. After adequate treatment and immobilization are instituted, the fracture should resume normal healing. Nonunion is a lack of bony healing that persists without proper treatment and fixation. Subacutely, plain radiographs show no healing between bone fragments and, chronically, show rounding of the fracture segment edges. Malunion is the improper alignment of a healed fracture. However, in some cases, absolute prefracture alignment may not be necessary to restore full function. This complication may also be amenable to treatment with orthodontics. [14, 15, 16]

Preferred examination

The radiologic workup of a suspected mandibular fracture initially depends on whether the patient presents with an isolated injury or with multi-injury trauma. If only an isolated mandibular fracture is suspected, radiographic evaluation should begin with the acquisition of a posteroanterior (PA) view, a Towne view (anteroposterior [AP] axial view), and bilateral oblique views. This is a typical, routine mandible series (see the images below). CT scanning—particularly helical CT and panoramic imaging—in addition to the basic mandibular radiographic study will identify all but the most subtle fractures. CT is the current diagnostic tool of choice for the radiographic evaluation and diagnosis of mandible fractures. [5, 3, 6, 7]

A panoramic tomographic view (Panorex view) [6, 7, 4] shows the entire mandible in one plane. If the results of these studies are equivocal or if more definition is requested, further specific views, such as the lateral, Waters (occipitomental view), periapical, or basal (submentovertex view), can be obtained (see the images below). Because of the high accessibility of multidetector CT and its use as a first-line examination for imaging the face and orbits, CT is now widely accepted as a primary imaging modality. [17]

Helical CT imaging in some studies have shown 100% sensitivity in diagnosing mandible fractures, compared with 86% sensitivity with panoramic tomography imaging. Together with 3D reconstruction, CT is considered the diagnostic tool of choice for the radiographic evaluation and diagnosis of mandible fractures. [6, 7]

Open-mouth lateral radiographic view of both condyles. Note that the condyles are posterior to the eminence of the temporal bone. No dislocation is observed.

Open-mouth lateral radiographic view of both condyles. Note that the condyles are posterior to the eminence of the temporal bone. No dislocation is observed.

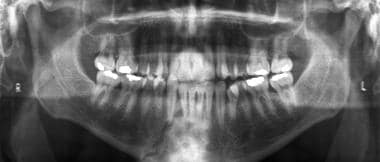

Panoramic radiographic image that was obtained after maxillary-mandibular fixation (wiring the jaw shut) of a right angle and left symphyseal fracture.

Panoramic radiographic image that was obtained after maxillary-mandibular fixation (wiring the jaw shut) of a right angle and left symphyseal fracture.

Panoramic radiographic image shows a left angle fracture extending to and dislodging the molar. This image also shows a right symphyseal fracture.

Panoramic radiographic image shows a left angle fracture extending to and dislodging the molar. This image also shows a right symphyseal fracture.

Panoramic radiographic image of the left angle fracture. Note that the back left molar is now horizontal.

Panoramic radiographic image of the left angle fracture. Note that the back left molar is now horizontal.

Panoramic radiographic image of a left body and angle fracture. This image depicts extension and fracture of a tooth.

Panoramic radiographic image of a left body and angle fracture. This image depicts extension and fracture of a tooth.

Panoramic radiographic image of a fracture of the left symphysis and right body. The body fracture extends through a tooth. This is considered a compound fracture.

Panoramic radiographic image of a fracture of the left symphysis and right body. The body fracture extends through a tooth. This is considered a compound fracture.

Poor-quality radiographic images should not be accepted. This repeat panoramic image reveals a right parasymphyseal fracture. Note also that the patient has a left condylar fracture.

Poor-quality radiographic images should not be accepted. This repeat panoramic image reveals a right parasymphyseal fracture. Note also that the patient has a left condylar fracture.

A retrospective study of 42 patients showed that initial helical CT scans depicted 100% of mandibular fractures, whereas the initial panoramic imaging showed only 86% of such fractures that were eventually demonstrated. [6] However, results from the same study also suggested that the bony detail of alveolar-ridge tooth-root fractures were better evaluated by using panoramic imaging.

For the CT scan examination, direct coronal and axial imaging should be attempted, depending on the patient's mobility. The direct coronal (or reverse coronal) series requires the patient's neck to be hyperextended, which is often not possible for patients who are in a spinal fixation collar. If direct coronal scans cannot be obtained, thinner axial sections (< 3 mm) should be included in the protocol to allow for enhanced detail on the sagittal and coronal reconstructed images. As fast, thin-section, multidetector-row CT (MDCT) scanners become common, the consideration regarding the patient's mobility is less of an issue, as motion artifact is greatly reduced, with MDCT scanners providing an alternative to direct coronal imaging. CT scanning is most valuable in the assessment of suspected high-condylar fractures that are difficult to see on plain radiographs. [6, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 4]

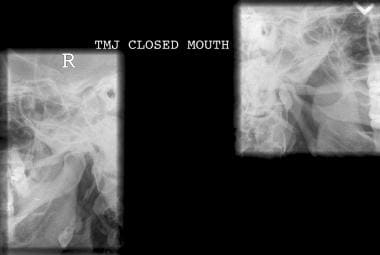

Patients with a suspected mandibular dislocation or limited excursion should undergo lateral imaging of the TMJs, with the acquisition of both open-mouth and closed-mouth views. This type of injury may also be examined by means of real-time fluoroscopy. Alternatively, open- and closed-mouth CT scanning may be performed (see the images below).

Fluoroscopic image showing the left temporomandibular joint with the patient's mouth closed. The condyle appears slightly more anterior than normal.

Fluoroscopic image showing the left temporomandibular joint with the patient's mouth closed. The condyle appears slightly more anterior than normal.

With the patient's mouth open, the left temporomandibular joint (TMJ) shows some mild dislocation in this radiographic image. The mandibular condyle is overlying the articular eminence of the temporal bone on this view. On open-mouth views, the condyle may normally lie just below the eminence, just not anterior to it.

With the patient's mouth open, the left temporomandibular joint (TMJ) shows some mild dislocation in this radiographic image. The mandibular condyle is overlying the articular eminence of the temporal bone on this view. On open-mouth views, the condyle may normally lie just below the eminence, just not anterior to it.

Conversely, in patients with suspected mandibular fractures that are associated with major trauma or multiple injuries, radiography is usually limited to the acquisition of AP and lateral projections, immediately followed by thin-section CT scanning, with a section thickness of approximately 1.0-3.0 mm. Images should be reconstructed in both the coronal and sagittal planes.

Despite being visually impressive, 3-dimensional (3-D) reconstructed CT scan images are of questionable value in detecting fractures when compared with planar images. However, once a fracture is identified, 3-D images may be helpful in depicting the spatial relationships among fragments when planning for surgery and/or other treatment. [18, 19, 24, 20] Generally, 3-D images are not useful unless they are constructed from high-resolution thin-section CT scans.

Lastly, if a broken tooth or broken dentures are incidentally detected in the imaging studies, chest radiography should be performed to rule out the aspiration of teeth or other dental hardware.

Limitations of techniques

The limitations of routine radiography include diminished sensitivity, poor technique, and lack of patient cooperation. Often, the proximal portion of the mandibular condyle is not visualized on any view. Sagittal fractures of the condyle are especially hard to identify. Oblique views are often acquired with overlap of the contralateral side (body, angle, and/or ramus) of the mandible. The symphyseal region is notoriously hard to evaluate because of overlap from the cervical spine. In this instance, a Waters or basal view may help visualize the symphysis.

The panoramic view (Panorex view) is even more affected by poor technique and lack of patient cooperation. Furthermore, the patient must be upright and hemodynamically stable for this examination. As such, panoramic imaging is not suitable in most trauma cases. In addition, many smaller emergency departments may not have the specialized equipment or the trained technologists that are needed for this modality. As on routine radiographs, panoramic views may not fully demonstrate the condyles, which can be obscured.

With CT scanning, mandibular fractures that are oriented in the same plane as the CT scan section can be obscured. For instance, a horizontal fracture through the mandibular body can be difficult to detect on axial CT images.

Motion artifact can hide even obvious fractures, which is even more true for reconstructed images. Dental work and fillings also create artifacts, but such artifacts are often not severe enough to interfere with the diagnosis.

A CT scan examination is relatively expensive compared with standard radiography. With any CT examination, the radiation dose to the patient is greater than that which is required for standard radiography. The typical effective dose-equivalent value of one head CT scan series is 200-400 millirems (mrems), compared with 10-20 mrems per plain radiograph. As with the Panorex equipment, there may sometimes be limited availability of CT scanners in small centers, especially after hours.

Radiography

The nature of the trauma and the direction of the force that is applied often foretell the type of fracture injury. A patient who is hit on the side of his or her face often presents with an ipsilateral body fracture and a contralateral condylar fracture. An impact at the central symphysis (as with a head hitting a dashboard) can result in bilateral condylar fractures with a symphyseal or parasymphyseal fracture (the classic "triple fracture").

It is important to evaluate the adequacy of the radiographs. Besides adequate image quality, the absence of significant rotational malalignment of the PA, Towne, and panoramic views should be verified. On oblique views, the opposite mandible body should not be superimposed over the side that is being evaluated. [3, 4]

Next, the cortical margin of all portions of the mandible should be traced. Often, only slight discontinuity of the cortex is seen. An indirect sign of mandibular fracture is any malocclusion or displacement of the teeth. In cases in which there is significant displacement of bone fragments, the identification of a fracture is an easy matter. However, because of the muscular attachments of the jaw, some fractures may be held in apposition. These are labeled the favorable fractures. Mandibular fractures can be labeled as horizontally or vertically favorable or unfavorable. In general, the muscular attachments of the mandible pull the anterior fragments posteriorly or inferiorly. Posterior fragments are generally pulled superiorly and medially.

Edentulous patients often have greater displacement of bone fragments due to the lack of the structural stability of the mandibular alveolus and dentition.

If a fracture occurs at the base of the condyle, the base is often pulled medially by the lateral pterygoid muscle up to 90º with the ramus. This finding is often accompanied by dislocation of the condyle from the TMJ.

A dislocation should not be the interpretation in cases in which the condyle is only below the articular eminence. This finding is normal in the open-mouth position. In a true dislocation, the mandibular condyle is anterior to the articular eminence.

In cases of bilateral condylar fractures with a symphyseal fracture (the triple fracture), the magnification sign may be seen, in which the lower jaw appears magnified compared with the upper jaw because bilateral lateral displacement of the mandibular bodies is present (see the image below).

Anteroposterior radiographic image shows a right ramus and left parasymphyseal fracture. This patient has the subtle magnification sign, with the right portion of the mandible appearing slightly magnified compared with the maxilla. This sign is due to lateral displacement of the right body.

Anteroposterior radiographic image shows a right ramus and left parasymphyseal fracture. This patient has the subtle magnification sign, with the right portion of the mandible appearing slightly magnified compared with the maxilla. This sign is due to lateral displacement of the right body.

The mandibular grooves should be traced bilaterally. Special attention should be paid to the condyles and symphysis because these areas often hide subtle fractures. Fractures of the alveolar ridge should be sought. An intraoral image may be required to more closely examine a tooth root. (Note: The intraoral film and other special dental views are often obtained in a dental surgery department rather than the typical radiology department.)

Fractures may also be classified as greenstick (seen in children), simple, compound, comminuted, or pathologic. Compound fractures are those that communicate with the external surface of the wound. Alveolar fractures are included in this category because intraoral bacteria can infect the broken tooth and the underlying mandible (see the image below).

Panoramic radiographic image of a fracture of the left symphysis and right body. The body fracture extends through a tooth. This is considered a compound fracture.

Panoramic radiographic image of a fracture of the left symphysis and right body. The body fracture extends through a tooth. This is considered a compound fracture.

If a fracture is seen in a patient who has a history of only minimal trauma, the fracture site should be reevaluated for any evidence of an underlying bone tumor or periapical abscess.

Again, the ring or pretzel principle of the mandible should always be remembered: if 1 fracture is present, look for another fracture.

Degree of confidence

If radiographic findings are still equivocal for a suspected fracture, repeat or additional views should be considered. If the new radiographic findings remain equivocal, a CT scan evaluation should be performed.

False positives/negatives

The PA view is used to evaluate the entire mandible. However, the symphysis is often obscured by the cervical spine, and the condyles can be superimposed over the mastoid process and occipital bone. A Waters view or a basal view should be obtained to better evaluate the symphysis to negate the overlap of the cervical spin. The Towne view is primarily used to view the condyles, but again, bone overlap is common. Among all facial fractures, mandibular condyle fractures are the ones that are most commonly undiagnosed (see the image below).

Possible false-positive radiographic finding of a mandibular fracture. The anterior margin of C2 often simulates a fracture of a condyle. Here, although the margin is too obvious to be mistaken for a fracture, the orientation of the anterior cortex of C2, which overlaps the left condyle, is demonstrated.

Possible false-positive radiographic finding of a mandibular fracture. The anterior margin of C2 often simulates a fracture of a condyle. Here, although the margin is too obvious to be mistaken for a fracture, the orientation of the anterior cortex of C2, which overlaps the left condyle, is demonstrated.

Another important cause of false-negative results is not identifying any underlying bone pathology, such as a fracture resulting from a periapical abscess. This error is most likely due to the satisfaction-of-search phenomenon, but not identifying a pathologic lesion can lead to delayed healing, delayed treatment, and, possibly, later osteomyelitis.

The normal mandibular groove should not be mistaken for a fracture. This structure is best seen on an oblique view. The normal appearance is 2 fine, parallel lines of cortical attenuation (see the images below).

Many structures can overlap on the plain radiographic series. These structures include vertebral bodies and soft tissues. In addition, air within the pharynx, bony ridges, and sinuses of the skull and/or face can also simulate fracture. The differentiation of these findings is the primary reason for the continued and increased use of CT scanning in the evaluation of questionable maxillofacial fractures.

Computed Tomography

CT scanning is the best method for detecting subtle or questionable fractures. CT scanning can also better elucidate hard-to-see fractures through the thin cortex of a pathologic lesion. With sagittal and coronal reconstructions, CT scans can depict all the portions of the mandible in 3 planes, but direct coronal views are always preferred. Besides identifying the fracture, it is easier to determine the degree of fragment displacement with CT scanning than with plain radiography. However, if the fracture is in the same plane as the CT scan section or if patient movement is excessive (this is most problematic with reconstructions), a fracture can be easily obscured. [21, 22, 25, 26] Motion artifact on reconstructed CT scan images can mimic a fracture. To reduce this artifact, the section thickness can be reduced and the sections can be overlapped.

Indications for CT imaging of the mandible include the following [4] :

-

In all unstable patients where the suspicion of mandibular fracture is present.

-

When there are ongoing concerns that a fracture is likely despite not being demonstrated on radiographs.

-

In all patients with a radiographic diagnosis of a fracture that would be amenable to closed or open reduction.

The CT scout image (computer-generated digital radiograph) should be evaluated because it may provide an approximation of the AP and lateral radiographic views. However, the scout image should not be considered a replacement for the lateral or AP images because the sensitivity of the scout image is much lower than that of the direct plain image. [4]

An internal study at the authors' institution (Santa Clara Valley Medical Center) was conducted to examine this issue. In the study, 400 trauma patients with mandibular fractures were retrospectively reexamined to determine if the CT scout images could have been used to predict an unknown mandibular fracture (before plain radiographs were obtained). The conclusion was that the scout images were not adequate as replacements for the AP and lateral plain images. This finding was partially based on the wide variations in the quality and positioning of the scout scans; more importantly, the finding was based on the low sensitivity of the scout images in the detection of fractures. However, looking at all of the images is still prudent; in the same internal study, most of the fractures that were suspected could be seen on the scout scan.

Using multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT), investigators found that multiple mandibular fractures of paramedian and condylar type may be a stronger indicator for temporal bone fractures. This study suggests that patients with mandibular fracture, especially the paramedian and condylar type, should be examined for coexisting temporal bone fracture using MDCT. [27]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Whereas CT scanning is used to evaluate the position of a condyle relative to the TMJ, MRI can be performed to evaluate the position and morphology of the cartilage of the TMJ. [28, 29, 30] MRI is best for evaluating a torn meniscus or a displaced disk (internal derangement), but rarely is trauma the instigating factor for this study. [31] As evaluated with MRI, TMJ pathology is most often degenerative in nature. This modality is also rarely used to evaluate for osteomyelitis that is secondary to mandibular fractures. [32]

Nogami et al studied 25 joints in 23 patients to determine the relationship between MRI evidence of joint effusion and concentrations of cytokines in synovial fluid samples from patients with mandibular condyle fractures. The results showed a correlation that could support arthrocentesis as a treatment modality for high condylar fractures. [32]

-

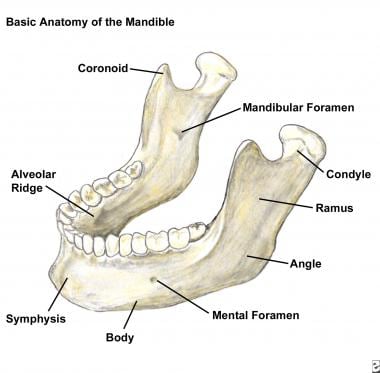

Basic anatomy of the mandible.

-

This midline sagittal drawing illustrates the anterior attachments of the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles. If the symphysis becomes a free fragment (as with bilateral parasymphyseal fractures), the symphysis retracts posteriorly, compromising the airway. The anterior belly of the digastric muscle is not depicted in the image because it is lateral to this central section.

-

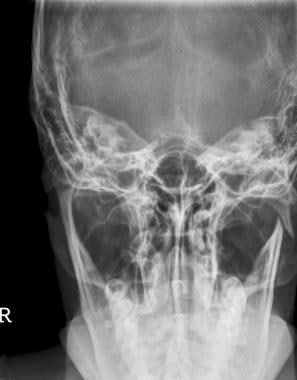

The normal Towne view in this radiograph shows the mandibular condyles well.

-

This right oblique radiograph clearly demonstrates the normal right mandibular groove.

-

The coronoid is best seen on an oblique radiographic view.

-

Sagittal computed tomography scan reconstruction shows the normal superior margin of the mandibular groove on the right side. This may be mistaken for a fracture.

-

Normal Waters radiographic view. In addition to the symphysis, the coronoids are depicted on this radiograph as well.

-

Normal basal (submentovertex) radiographic view.

-

Normal panoramic radiographic view.

-

Panoramic radiographic image in an edentulous patient.

-

Plain oblique radiographic view in an edentulous patient.

-

Panoramic radiographic image in a 5-year-old boy.

-

Posteroanterior radiographic view of a left condylar fracture.

-

Towne radiographic view of the left condylar fracture.

-

Axial computed tomography scan of a left condylar fracture, with lateral displacement of the proximal condylar fragment.

-

Axial computed tomography scan of a right subcondylar fracture.

-

Reconstructed coronal computed tomography scan of a right subcondylar fracture.

-

This example of a right subcondylar fracture was not well depicted on a right oblique radiographic view.

-

This coronal computed tomography scan clearly shows a right subcondylar fracture.

-

Possible false-positive radiographic finding of a mandibular fracture. The anterior margin of C2 often simulates a fracture of a condyle. Here, although the margin is too obvious to be mistaken for a fracture, the orientation of the anterior cortex of C2, which overlaps the left condyle, is demonstrated.

-

Axial computed tomography scan of a comminuted left ramus fracture.

-

Direct coronal computed tomography scan of a left ramus fracture.

-

Anteroposterior radiographic image shows a right ramus and left parasymphyseal fracture. This patient has the subtle magnification sign, with the right portion of the mandible appearing slightly magnified compared with the maxilla. This sign is due to lateral displacement of the right body.

-

Panoramic radiographic image of a right angle and left symphyseal fracture.

-

Panoramic radiographic image that was obtained after maxillary-mandibular fixation (wiring the jaw shut) of a right angle and left symphyseal fracture.

-

Panoramic radiographic image shows a left angle fracture extending to and dislodging the molar. This image also shows a right symphyseal fracture.

-

Left oblique radiographic image shows a left angle fracture in a patient with a dislodged molar tooth.

-

Panoramic radiographic image of the left angle fracture. Note that the back left molar is now horizontal.

-

Posteroanterior radiographic view showing a left angle fracture.

-

Left angle fracture on a left oblique radiographic image.

-

Direct coronal computed tomography scan of a left angle fracture.

-

Sagittal computed tomography scan reconstruction of a left angle fracture.

-

Axial computed tomography scan of a right body fracture.

-

A right body fracture is barely seen on this panoramic radiographic image.

-

Radiograph of a comminuted fracture of the body and symphysis caused by a gunshot wound.

-

Axial computed tomography scan of a lytic lesion of the right body (giant cell granuloma). This lesion is predisposed to pathologic fracture.

-

Panoramic radiographic image of the lesion through the right body.

-

3-dimensional (3-D) reconstructed computed tomography scan of the lytic lesion of the right body.

-

Posteroanterior radiographic view of a fracture of the left body and angle.

-

Oblique radiographic image of a fracture of the left body and angle.

-

Towne radiographic view of a left body and angle fracture.

-

Panoramic radiographic image of a left body and angle fracture. This image depicts extension and fracture of a tooth.

-

Left oblique radiographic image that was obtained after fixation of a fracture of the left body and angle.

-

Subtle left body fracture on a left oblique radiographic image.

-

Radiograph of a right body fracture.

-

Axial computed tomography scan of a right body fracture.

-

Panoramic radiographic image of a fracture of the left symphysis and right body. The body fracture extends through a tooth. This is considered a compound fracture.

-

Axial computed tomography scan in a patient with a right symphyseal fracture.

-

Prone hyperextended axial computed tomographic scan of a right symphyseal fracture.

-

Three-dimensional (3-D) computed tomographic scan of a right symphyseal fracture.

-

Three-dimensional (3-D) computed tomography scan of a right parasymphyseal fracture from a submentovertex projection.

-

Axial computed tomography scan depicting a free tooth fragment.

-

Free fragment of a molar seen on a right oblique radiographic image.

-

Coronal computed tomography scan showing an alveolar ridge fracture of the incisors.

-

Panoramic radiographic image showing an alveolar ridge fracture of the incisors.

-

Axial computed tomography scan showing a symphyseal fracture as well as a mandibular fracture.

-

Closed-mouth lateral radiographic view of both condyles. No dislocation is observed.

-

Open-mouth lateral radiographic view of both condyles. Note that the condyles are posterior to the eminence of the temporal bone. No dislocation is observed.

-

Oblique radiographic image showing a dislocation of the left mandibular condyle.

-

Fluoroscopic image showing the left temporomandibular joint with the patient's mouth closed. The condyle appears slightly more anterior than normal.

-

With the patient's mouth open, the left temporomandibular joint (TMJ) shows some mild dislocation in this radiographic image. The mandibular condyle is overlying the articular eminence of the temporal bone on this view. On open-mouth views, the condyle may normally lie just below the eminence, just not anterior to it.

-

Radiograph from a 6-year-old boy who was attacked by a dog. The lateral plain image does not show the suspected fracture or dislocation well; therefore, a computed tomography examination was ordered.

-

Axial computed tomography scan showing a normal right condyle in the temporomandibular joint.

-

The left condyle is anteriorly dislocated in this computed tomography scan. Note how fluid attenuation (blood) fills the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). This is aptly termed the empty TMJ sign of displacement.

-

Prone, direct coronal computed tomography scan shows an anterior left condylar dislocation.

-

Panoramic radiographic image in which the inferior margin of the symphysis is blurred and cut off.

-

Poor-quality radiographic images should not be accepted. This repeat panoramic image reveals a right parasymphyseal fracture. Note also that the patient has a left condylar fracture.

-

Posteroanterior radiographic view of the left condyle and right parasymphyseal fracture.

-

Towne radiographic view showing that the left condylar fracture is comminuted and distracted.

-

The examining physician should remember to check the mandible on a cervical spine image. On this lateral cervical spine radiograph, a fracture extends through the left mandibular angle.