Practice Essentials

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous environmental organisms that are normally found in soil and water and are resistant to extreme heat and pH, as well as many disinfectants and antibiotics, because of a highly protective, thick, lipid-rich cell wall. [1] They are an important cause of pulmonary infections in humans. [2] In 1968, Dr Wolinsky published the first comprehensive review, stating, "chronic pulmonary disease resembling tuberculosis [TB] represents the most important clinical problem associated with NTM." [3] Since then, a variety of manifestations of NTM infection have been described, but the lungs remain the most commonly involved site. [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

The increasing efficiency of microbiologic laboratories in isolating small quantities of organisms has made the distinction between colonization and infection more difficult. Therefore, diagnostic guidelines from the American Thoracic Society suggest that the presence of symptoms and radiographic evidence of infiltrates (nodular or cavitary disease) are essential adjuncts to the microbiologic diagnosis. [9, 10, 11]

(See the images below.)

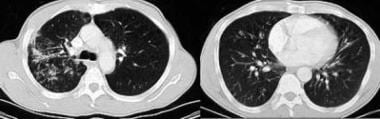

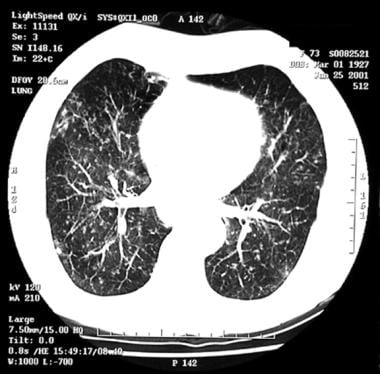

Images in a 50-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a worsening cough, and a low-grade fever of 3 months' duration show cavitating consolidation and volume loss, the primary pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. This particular patient had a Mycobacterium kansasii infection.

Images in a 50-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a worsening cough, and a low-grade fever of 3 months' duration show cavitating consolidation and volume loss, the primary pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. This particular patient had a Mycobacterium kansasii infection.

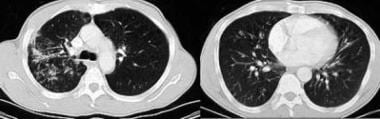

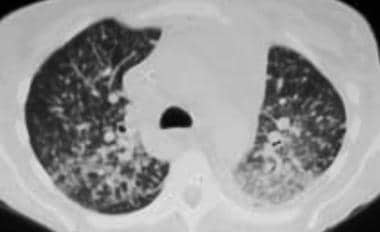

Chest CT scans in a patient with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection show nodules and multifocal bronchiectasis in the middle lobe and lingula.

Chest CT scans in a patient with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection show nodules and multifocal bronchiectasis in the middle lobe and lingula.

The prevalence of pulmonary NTM disease is increasing and occurs more frequently in the elderly and in patients with chronic underlying disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis, and interstitial lung disease. Cystic fibrosis significantly increases the risk for NTM pulmonary disease. [12] It may also afflict otherwise healthy individuals. [13, 14] The clinical presentation varies from mild disease that does not require treatment to significant disease that may be drug resistant or refractory to treatment. [14]

The best-studied NTM are slow-growing Mycobacterium avium (MAI) complex and Mycobacterium kansasii. Nontuberculosis mycobacteria are pathogenic mycobacteria, other than Mycobacterium leprae, that are not part of the tuberculosis complex. There are many other potentially pathogenic NTM organisms. Approximately 80% of pulmonary NTM infections are caused by M avium complex (MAC), and M abscessus accounts for 6-13%. [2] Typical treatment regimens consist of multiple antibiotics for prolonged durations. These regimens depend on the specific species, drug sensitivity, and severity of disease. Surgical intervention may be required in some situations.

MAI is the most common pathogen in the United States, followed by M kansasii, and MAI and then Mycobacterium xenopi are most common in Canada and in parts of Europe. M abscessus accounts for greater than 80% of cases of NTM lung disease due to rapidly growing mycobacterial species. [15]

Radiography

NTM infections are associated with a wide spectrum of radiologic findings, as demonstrated in the image below. [16, 17]

The nodular bronchiectatic pattern may be seen in healthy individuals and occurs predominantly in elderly females in the lingula or the middle lobe. This is also known as Lady Windermere syndrome; it was initially thought to be partly a result of volunatry cough suppression and was later linked to unique body and immune phenotypes. [18, 19]

Images in a 60-year-old woman with a chronic cough lasting for 1 year. Sputum cultures grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex). This is the other typical pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Note the prominent lingular bronchiectasis, fibrosis, and atelectasis. Significant middle lobe disease was also found.

Images in a 60-year-old woman with a chronic cough lasting for 1 year. Sputum cultures grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex). This is the other typical pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Note the prominent lingular bronchiectasis, fibrosis, and atelectasis. Significant middle lobe disease was also found.

In the most common group of patients—namely, elderly with COPD—the typical findings include linear and nodular opacities involving the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments of the lower lobes. Involvement of multiple segments is common. Unlike those of TB, NTM lesions are indolent and progress slowly. Marked fibrosis and atelectasis of affected zones are commonly seen, with traction bronchiectasis evident in the most affected areas. (See the image below.)

Images in a 50-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a worsening cough, and a low-grade fever of 3 months' duration show cavitating consolidation and volume loss, the primary pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. This particular patient had a Mycobacterium kansasii infection.

Images in a 50-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a worsening cough, and a low-grade fever of 3 months' duration show cavitating consolidation and volume loss, the primary pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. This particular patient had a Mycobacterium kansasii infection.

Degree of confidence

In NTM infections, chest radiographic findings are usually not specific, and they can also be seen in TB, granulomatous fungal infections, sarcoidosis, and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP). In appropriate clinical contexts, typical findings have a high predictive value. For example, patients with MAI infection may be distinguished from those with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) by the presence of widespread bronchiectasis, particularly if it involves the right middle lobe and the lingula. Cavitation is usually associated with positive sputum results.

False positives/negatives

Regarding false-positive results, normal anatomic variants are usually not confused with NTM infection. On the other hand, granulomatous processes such as TB, fungal infections, and sarcoidosis can all resemble NTM infections. Often, the colonization of a scarred or bronchiectatic lung cannot be distinguished from active infection causing scarring and/or bronchiectasis.

Regarding false-negative results, immunosuppressed patients commonly have normal findings on chest radiographs, or detectable parenchymal disease is absent. Findings of focal bronchiectasis associated with early NTM infections are also easily missed. Only 70% of patients with established bronchiectasis, as depicted on CT scans, have a detectable abnormality on chest radiographs.

Computed Tomography

Typical diagnostic features of NTM infections (particularly those due to MAI complex) in immunocompetent patients without underlying lung disease are the following: (1) multiple small parenchymal nodules in a centrilobular pattern, (2) associated multifocal bronchiectasis involving more than 1 lobe, and (3) progressive fibrosis and atelectasis of the affected areas. HRCT is useful in identifying these patterns. [11] (See the image below.)

Chest CT scans in a patient with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection show nodules and multifocal bronchiectasis in the middle lobe and lingula.

Chest CT scans in a patient with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection show nodules and multifocal bronchiectasis in the middle lobe and lingula.

In a large group of patients, the findings are similar to those of TB. Reticulonodular changes, along with cavitation, may be seen in an upper-lobe distribution. The additional information provided by CT is limited to better anatomic delineation of cavitation and the extent of disease.

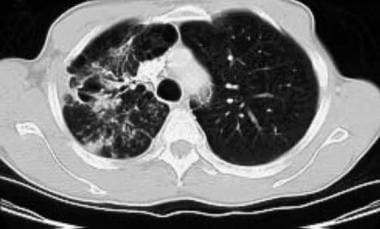

Consolidation and cavitation are frequently seen. The cavities vary in size and are radiologically indistinguishable from postprimary TB (see the image below). Endobronchial spread is the predominant mechanism of spread and can be seen in about half the cases. It is seen best on CT images as 5- to 10-mm centrilobular peribronchiolar opacities with clustering. It is unusual to see extensive adenopathy in this patient group. Pleural effusions are infrequent but not rare (10-20%).

CT chest image in a patient with Mycobacterium kansasii infection shows cavitation and fibrosis in the right upper lobe.

CT chest image in a patient with Mycobacterium kansasii infection shows cavitation and fibrosis in the right upper lobe.

A study comparing the CT findings in patients with bronchiectasis with and without NTM infections found patients without NTM infection more often showed peripheral ground-glass opacities and interstitial changes than patients with NTM infection. The study further reported that patients with NTM infection had higher prevalence of bronchiectasis in the middle lobes, extended bronchiolitis, more nodules, larger cavities and thickened bronchial walls. [20]

The second group of patients consists of middle-aged or elderly women without a history of lung disease. The symptoms are typically milder than those in other patients; the radiographs show scattered reticulonodular opacities without an upper-lobe predominance. CT imaging reveals more extensive disease with scattered centrilobular nodules, a tree-in-bud pattern, and focal bronchiectasis. In some cases, atelectasis and severe bronchiectasis of the middle lobe and/or lingula may be the only manifestations. Usually, no cavitation, pleural effusion, or extensive adenopathy is depicted.

Although MAI infections can be associated with a wide variety of radiologic patterns, findings of multifocal bronchiectasis with centrilobular nodules and patchy consolidation are highly predictive. When seen in its typical locations of the lingula or middle lobe in elderly females, MAI complex is also referred to as Lady Windermere syndrome. Similar findings are seen in rapidly growing NTM infections, with a more extensive and multilobar distribution of nodular bronchiectasis in M abscessus lung infection. [21]

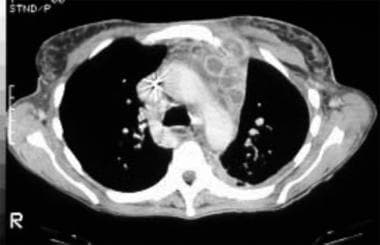

The presentation of immunocompromised patients is entirely different from the patterns mentioned above. Patients with clinical infection may have no radiographic abnormalities, presumably because of inadequate inflammatory response. Alternatively, lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions may be the only abnormalities, with no evidence of parenchymal disease (see the first image below). In other patients, segmental or lobar consolidation may be seen. Miliary spread is seen occasionally. The most common pattern is scattered alveolar opacities and bilateral nodules, but this is not specific for the disease (see the second and third images below). A high index of suspicion and microbiologic investigation are required for diagnosis.

HIV-positive patient with fever. Note the hypoattenuating lymphadenopathy with extension into the left chest wall. Biopsy samples revealed Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex).

HIV-positive patient with fever. Note the hypoattenuating lymphadenopathy with extension into the left chest wall. Biopsy samples revealed Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex).

CT scan obtained in a patient with an infection due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex).

CT scan obtained in a patient with an infection due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex).

Disseminated Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection in a patient with AIDS.

Disseminated Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection in a patient with AIDS.

Unusual radiographic presentations of NTM infections include solitary pulmonary nodules or masses (see the image below). The diagnosis is usually incidental in otherwise asymptomatic patients being examined for a malignancy.

Image in a 40-year-old man with HIV disease. Chest radiographs showed an anterior mediastinal mass, and the patient underwent transthoracic biopsy. Smears showed numerous acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and cultures grew Mycobacterium kansasii.

Image in a 40-year-old man with HIV disease. Chest radiographs showed an anterior mediastinal mass, and the patient underwent transthoracic biopsy. Smears showed numerous acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and cultures grew Mycobacterium kansasii.

In patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, a high index of suspicion must be maintained because a wide spectrum of radiologic findings can be seen. The disease can resemble disseminated primary TB or can cause localized pneumonia. Lymphadenopathy and/or pleural effusions are common. In patients with these findings, CT aids in the identification of subtle disease that is missed on the chest radiographs.

Lymph nodes with hypoattenuating centers that suggest necrosis are associated with mycobacterioses. CT is more sensitive than other techniques in the detection of cavitation and effusions. Subtle centrilobular nodules may be the only sign of infection in immunocompromised patients.

In summary, NTM infection of the lung is a diagnosis that requires the radiologic or pathologic demonstration of disease, followed by definitive microbiologic isolation of the organism.

Degree of confidence

CT findings of NTM infections are often nonspecific. However, typical patterns such as multifocal bronchiectasis with patchy consolidation and centrilobular nodules have been defined; these have a high positive predictive value. In bronchiectatic patients with multiple small lung nodules whose culture results are positive for MAI complex, CT has a sensitivity of 80%, a specificity of 87%, and an accuracy of 86%.

Although certain patterns on HRCT scans are associated with high specificity, false-positive results can be seen with any radiographic presentation. Atypical presentations of pulmonary TB can mimic those of NTM lung disease, as can those of granulomatous fungal infections.

The high sensitivity of HRCT results in a low false-negative rate in immunocompetent patients. Immunocompromised patients usually have abnormalities on CT scans; however, these findings can be atypical, and parenchymal disease can be subtle.

-

Images in a 50-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a worsening cough, and a low-grade fever of 3 months' duration show cavitating consolidation and volume loss, the primary pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. This particular patient had a Mycobacterium kansasii infection.

-

CT chest image in a patient with Mycobacterium kansasii infection shows cavitation and fibrosis in the right upper lobe.

-

Chest CT scans in a patient with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection show nodules and multifocal bronchiectasis in the middle lobe and lingula.

-

Chest CT scan showing centrilobular nodules.

-

Images in a 60-year-old woman with a chronic cough lasting for 1 year. Sputum cultures grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex). This is the other typical pattern associated with nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Note the prominent lingular bronchiectasis, fibrosis, and atelectasis. Significant middle lobe disease was also found.

-

HIV-positive patient with fever. Note the hypoattenuating lymphadenopathy with extension into the left chest wall. Biopsy samples revealed Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex).

-

CT scan obtained in a patient with an infection due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex).

-

Disseminated Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI complex) infection in a patient with AIDS.

-

Image in a 40-year-old man with HIV disease. Chest radiographs showed an anterior mediastinal mass, and the patient underwent transthoracic biopsy. Smears showed numerous acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and cultures grew Mycobacterium kansasii.

![Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC) (Mycobacterium Avium-Intracellulare [MAI])](https://img.medscapestatic.com/pi/meds/ckb/31/37331tn.jpg?interpolation=lanczos-none&resize=75:*)