Practice Essentials

Tuberculosis (TB) has existed for millennia, and despite initial declines in its incidence during the middle of the 20th century, the disease has been reemerging across the world. [1] Tuberculosis results from infection by any of the TB complex mycobacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M bovis, M africanum, M microti, and M canetti. [2] In the United States, annual incidence of tuberculosis is 30 per 1 million people. [3] TB can be divided into primary, progressive-primary, and postprimary forms on the basis of the natural history of the disease. Postprimary TB results from either reactivation of a latent primary infection or, less commonly, from the repeat infection of a previously sensitized host. Reinfection is possible because the type of immune response required, cell-mediated immunity, needs a certain local inflammatory response to locate lesions. [4, 5, 6]

The term "postprimary" is preferred to "reactivation" when referring to the clinical diagnosis, because firmly distinguishing recurrence from an antecedent infection is impossible in most cases. Approximately 10% of all infected patients are likely to develop reactivation, and the risk is highest within the first 2 years or during periods of immunosuppression. [7, 8, 9, 10] However, lifetime risk of reactivation TB from latent TB infection depends on the person's age when infected and the presence of other medical conditions associated with TB progression. [11]

Over the years, improvements in technology, coupled with extensive investigation into the radiologic patterns of pulmonary TB, have resulted in diagnostic imaging being an essential adjunct to the clinical and microbiologic diagnosis of this disease. [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17] No radiologic study displays findings that are specific for tuberculosis. A cavitary process that is demonstrated on chest radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans in the apical and posterior segments of the upper pulmonary lobe or in the superior segments of the lower lobes is likely to be TB; however, differential considerations include other diseases, such as histoplasmosis and other fungal infections, bacterial abscesses, and necrotic neoplasms, especially lung neoplasms. [18, 19, 20]

Although the findings of currently active TB can often be differentiated from previous scarring on radiologic images, the possibility of latent or temporarily quiescent infection exists, and healed or inactive TB should not be diagnosed without adequate clinical information and/or the finding of calcified lesions. Radiographic follow-up is recommended in all cases of TB because it provides valuable information regarding the extent of the disease and its progression.

(Images related to postprimary tuberculosis are provided below.)

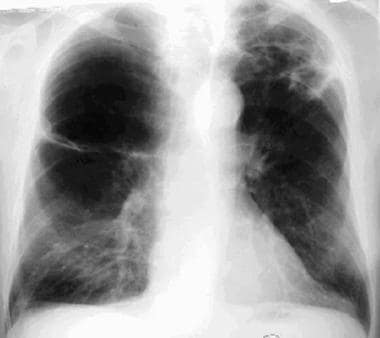

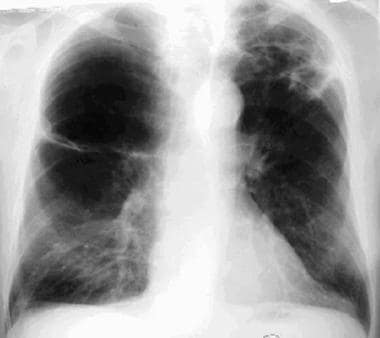

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. The patient presented with a history of recent onset of coughing, as well as had a fever and night sweats. This image shows right-upper lung (RUL) bullous disease and suggests a left-lower lung (LLL) cavity. The LLL abnormality was new, appearing since his previous examination a year earlier, which was performed before the onset of his recent symptoms.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. The patient presented with a history of recent onset of coughing, as well as had a fever and night sweats. This image shows right-upper lung (RUL) bullous disease and suggests a left-lower lung (LLL) cavity. The LLL abnormality was new, appearing since his previous examination a year earlier, which was performed before the onset of his recent symptoms.

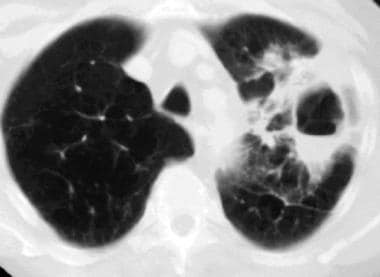

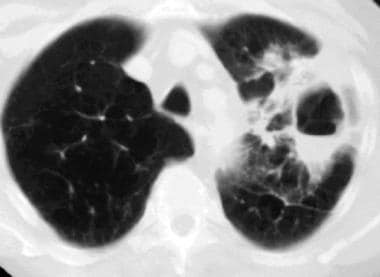

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. This image shows a thick-walled, left-lower lung (LLL) cavity with an air-fluid level; a smaller, more medial cavity; and some lung parenchymal opacities. Acid-fast organisms were detected in the patient's sputum, and the culture results indicated the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. This image shows a thick-walled, left-lower lung (LLL) cavity with an air-fluid level; a smaller, more medial cavity; and some lung parenchymal opacities. Acid-fast organisms were detected in the patient's sputum, and the culture results indicated the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in an 83-year-old woman who was sent to the emergency department from her nursing home because of a recent history of productive cough, weight loss, and fatigue. Until recently, the woman was the social director at the nursing home. In her younger years, the patient had tuberculosis during her first pregnancy; this illness occurred before antibiotic therapy was used to treat tuberculosis. This image demonstrates extensive bilateral lung nodules and a cavity in a partially collapsed right upper lung. Sputum cultures were positive for tuberculosis. The nodules indicate endobronchial spread of the tuberculosis.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in an 83-year-old woman who was sent to the emergency department from her nursing home because of a recent history of productive cough, weight loss, and fatigue. Until recently, the woman was the social director at the nursing home. In her younger years, the patient had tuberculosis during her first pregnancy; this illness occurred before antibiotic therapy was used to treat tuberculosis. This image demonstrates extensive bilateral lung nodules and a cavity in a partially collapsed right upper lung. Sputum cultures were positive for tuberculosis. The nodules indicate endobronchial spread of the tuberculosis.

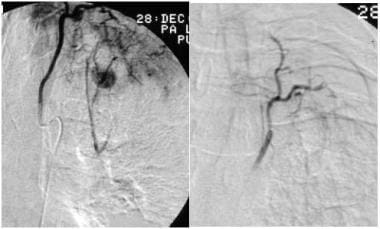

Selective bronchial arteriogram in a patient with history of tuberculosis who presented with massive hemoptysis. This image reveals a Rasmussen aneurysm (left) that was embolized (right).

Selective bronchial arteriogram in a patient with history of tuberculosis who presented with massive hemoptysis. This image reveals a Rasmussen aneurysm (left) that was embolized (right).

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a young female patient who presented with a cough, positive findings on skin testing with purified protein derivative of tuberculin (PPD), and a pleural effusion that was positive for acid-fast bacilli. This image shows a left pleural effusion and left lower-lobe consolidation.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a young female patient who presented with a cough, positive findings on skin testing with purified protein derivative of tuberculin (PPD), and a pleural effusion that was positive for acid-fast bacilli. This image shows a left pleural effusion and left lower-lobe consolidation.

In immunocompromised patients, postprimary TB may mimic primary TB, and the condition can appear with pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy, or miliary spread. The usual pattern of cavitary upper-lobe disease is less common in immunocompromised hosts than in immunocompetent hosts. [21]

Stout et al reviewed 241 radiographs from 99 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis to determine reliability in predicting tuberculosis relapse. Agreement among 3 independent readers was very good for the findings of bilateral disease and cavitation, but substituting a consensus interpretation for the original interpretation increased the odds ratio for the association between cavitation on early chest radiograph and subsequent tuberculosis relapse from 4.97 to 8.97. According to the authors, improving the reliability of these findings could improve the utility of chest radiographs for predicting tuberculosis relapse. [22]

Sant'Anna et al, in a Brazilian study, observed the radiographic features of young patients with pulmonary TB and found cavitary lesions in 67 of 243 patients (27.6%) between the ages of newborn and 15 years, and in 116 of 321 patients (36.1%) in adolescents aged 16 to 19 years. The most common radiographic lesions were postprimary tuberculosis (53.3%), tuberculous expansile pneumonia (27%), and primary complex with adenomegaly (1.8%). [23]

In a Japanese study, Nakanishi et al concluded that even in cases of negative sputum smears, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scanning can be used to predict the risk of pulmonary TB with good reproducibility and to indicate which patients have a high probability of pulmonary TB. The authors examined findings in 116 patients with suspected pulmonary TB who had negative sputum smears for acid-fast bacilli. They found that large nodules, tree-in-bud appearance, lobular consolidation, and the main lesion being located in S1, S2, and S6 were significantly associated with an increased risk of pulmonary TB. [24]

Radiography

Pulmonary tuberculosis, especially postprimary disease, nearly always causes abnormalities on chest radiographs. Typically, the disease is parenchymal without nodal enlargement, and it manifests as cavitary lesions. Upper-lobe involvement with cavitation and the absence of lymphadenopathy are helpful in distinguishing postprimary TB from primary TB. [25] In addition to the usually involved pulmonary segments—namely, the apical or posterior segments of the upper lobe or the superior segment of a lower lobe—anterior or basal segments may be involved in as many as 75% of cases. [26]

TB cannot be confidently diagnosed on the basis of chest radiographic findings alone because the imaging results can often be normal in primary TB. Normal findings are unusual in postprimary lung disease, but they cannot be used to exclude extrapulmonary TB. However, the combined positive predictive value is high for the typical symptoms of the disease and the finding of cavitary upper-lobe infiltrates on chest radiographs. Sarcoidosis, granulomatous fungal infections, Nocardia infections, and atypical mycobacterioses are the conditions that most commonly mimic pulmonary TB.

(See the image below.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. The patient presented with a history of recent onset of coughing, as well as had a fever and night sweats. This image shows right-upper lung (RUL) bullous disease and suggests a left-lower lung (LLL) cavity. The LLL abnormality was new, appearing since his previous examination a year earlier, which was performed before the onset of his recent symptoms.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. The patient presented with a history of recent onset of coughing, as well as had a fever and night sweats. This image shows right-upper lung (RUL) bullous disease and suggests a left-lower lung (LLL) cavity. The LLL abnormality was new, appearing since his previous examination a year earlier, which was performed before the onset of his recent symptoms.

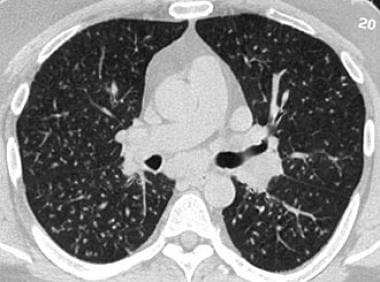

Cavitation is a distinguishing feature of postprimary TB; this finding is seen on chest radiographs in about half of the cases and is discernible on chest CT scans in most cases. Typical cavities are thick walled and irregular. Air-fluid levels are uncommon and usually indicate superinfection; however, in 9% of cases, air-fluid levels can be seen in other circumstances. The persistence of cavitation without healing is unusual and should be investigated to exclude mycetomas, particularly in patients with persisting hemoptysis. [27] Cavitation can lead to endobronchial spread to the remaining lung or rupture into the pleural space, where it can cause an empyema or bronchopleural fistula. Cavitation can also cause pseudoaneurysms of the pulmonary artery, which are called Rasmussen aneurysms.

(See the image below.)

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in an 83-year-old woman who was sent to the emergency department from her nursing home because of a recent history of productive cough, weight loss, and fatigue. Until recently, the woman was the social director at the nursing home. In her younger years, the patient had tuberculosis during her first pregnancy; this illness occurred before antibiotic therapy was used to treat tuberculosis. This image demonstrates extensive bilateral lung nodules and a cavity in a partially collapsed right upper lung. Sputum cultures were positive for tuberculosis. The nodules indicate endobronchial spread of the tuberculosis.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in an 83-year-old woman who was sent to the emergency department from her nursing home because of a recent history of productive cough, weight loss, and fatigue. Until recently, the woman was the social director at the nursing home. In her younger years, the patient had tuberculosis during her first pregnancy; this illness occurred before antibiotic therapy was used to treat tuberculosis. This image demonstrates extensive bilateral lung nodules and a cavity in a partially collapsed right upper lung. Sputum cultures were positive for tuberculosis. The nodules indicate endobronchial spread of the tuberculosis.

Miliary spread is less common in postprimary TB and is caused by erosion of bronchial vessels or pulmonary veins.

(See the image below.)

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 31-year-old man with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and a previous history of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). The patient developed shortness of breath, high-grade fever, and generalized lymphadenopathy. This image shows right mediastinal adenopathy and bilateral, uniformly tiny nodules. The man underwent biopsy by means of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), with the resultant diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 31-year-old man with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and a previous history of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). The patient developed shortness of breath, high-grade fever, and generalized lymphadenopathy. This image shows right mediastinal adenopathy and bilateral, uniformly tiny nodules. The man underwent biopsy by means of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), with the resultant diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis.

Most cases of TB in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or other immunosuppressive diseases are secondary to reactivation of a latent infection. However, a hypersensitive response or the absence of adequate immunity results in disease that behaves like primary TB. Miliary spread with systemic dissemination is more common in these immunocompromised individuals than in the healthy population. In these patients, radiographic findings are atypical, and the images often show diffuse dissemination, with striking lymphadenopathy and/or pleural effusions. Parenchymal involvement can range from consolidation to the absence of any lung opacities. Pleural effusion and parenchymal involvement are seen in the image below.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a young female patient who presented with a cough, positive findings on skin testing with purified protein derivative of tuberculin (PPD), and a pleural effusion that was positive for acid-fast bacilli. This image shows a left pleural effusion and left lower-lobe consolidation.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a young female patient who presented with a cough, positive findings on skin testing with purified protein derivative of tuberculin (PPD), and a pleural effusion that was positive for acid-fast bacilli. This image shows a left pleural effusion and left lower-lobe consolidation.

In the developed world, cavitation is uncommon in HIV-infected patients who have TB. In endemic areas, a more typical response, including upper-lobe disease and cavitation, is frequently seen in affected patients. This variance may be related to differences in the immune status of the patients.

TB and lung cancer coexist in as many as 5% of cases, but whether TB independently increases the likelihood of cancer remains unclear.

Computed Tomography

Because typical postprimary TB is readily seen on conventional chest radiographs, the major utility of CT scanning is for assessment of the extent and nature of the disease. CT scanning is more sensitive than chest radiography in depicting cavitation. The associated complications of postprimary TB, such as the erosion of vessels, rupture into the pleural space, and miliary and bronchogenic spread, are also better defined with CT scanning than with radiography. [28, 29, 30]

(See the images below.)

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. This image shows a thick-walled, left-lower lung (LLL) cavity with an air-fluid level; a smaller, more medial cavity; and some lung parenchymal opacities. Acid-fast organisms were detected in the patient's sputum, and the culture results indicated the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. This image shows a thick-walled, left-lower lung (LLL) cavity with an air-fluid level; a smaller, more medial cavity; and some lung parenchymal opacities. Acid-fast organisms were detected in the patient's sputum, and the culture results indicated the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a patient with treated postprimary cavitary tuberculosis who had persistent hemoptysis. This scan shows a right-upper lung cavity with a dependent mass within the cavity and air around it. This is the so-called crescent sign, which is a characteristic finding for a mycetoma, usually an aspergilloma.

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a patient with treated postprimary cavitary tuberculosis who had persistent hemoptysis. This scan shows a right-upper lung cavity with a dependent mass within the cavity and air around it. This is the so-called crescent sign, which is a characteristic finding for a mycetoma, usually an aspergilloma.

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window, from a patient with postprimary tuberculosis. This image shows a miliary tuberculous pattern. Used with permission (Amorosa, 1999).

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window, from a patient with postprimary tuberculosis. This image shows a miliary tuberculous pattern. Used with permission (Amorosa, 1999).

A tree-in-bud pattern of 5- to 10-mm centrilobular nodules has been associated with endobronchial spread on HRCT scans, which helps in identifying active disease. [31] Also, postprimary TB disease in immunocompromised patients may not be seen on chest radiographs. Mediastinal adenopathy, subtle pleural changes, and miliary lung parenchymal involvement are best detected with CT scanning.

Degree of confidence

Although no single radiologic feature is diagnostic of postprimary TB, a combination of upper-lobe opacities with a dominant cavitary process increases confidence in the diagnosis of TB. A tree-in-bud pattern is associated with endobronchial spread and suggests active disease.

Regarding false-positive findings, nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infections can mimic all radiologic findings that are associated with postprimary TB. [32] Typically, these findings are seen in elderly men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); in such patients, NTM infections should always be considered. Fungal infections, particularly histoplasmosis, may also result in similar findings. Cavitary lung disease that resembles TB has also been reported in cases of pyogenic infections, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, parasitic infections, bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), and malignancies.

Regarding false-negative findings, postprimary TB resembles primary TB in immunocompromised patients, and it can be radiologically misclassified. CT and/or HRCT scan results are unlikely to be completely normal in postprimary TB.

Nuclear Imaging

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans may be positive in cases of active tuberculosis. Positive results are usually found when malignancy is suspected during the workup of a lung abnormality.

Using a non-human primate model, Lin and colleagues reported that PET/CT can identify certain features that are associated with a higher risk of reactivation of latent TB. These factors include overall lung inflammation, individual granulomas in the lung with higher bacterial burden, and a site of infection outside the lungs. Such biomarkers may identify those people who would benefit most from treatment of latent TB to prevent reactivation. [33]

Current nuclear medicine tests are not specific for tuberculosis. There is increasing research on tagging nuclear medicine labels to molecular ligands for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB). While such molecular imaging is likely to be useful, it is yet to reach clinical practice. In one small study, [34] technetium-99m ciprofloxacin single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was found to have 89% positive predictive value and 83% negative predictive value for the diagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis. This approach is particularly promising in differentiating active tuberculosis from prior scarring.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. The patient presented with a history of recent onset of coughing, as well as had a fever and night sweats. This image shows right-upper lung (RUL) bullous disease and suggests a left-lower lung (LLL) cavity. The LLL abnormality was new, appearing since his previous examination a year earlier, which was performed before the onset of his recent symptoms.

-

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a 65-year-old man with a long history of smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and childhood tuberculosis. This image shows a thick-walled, left-lower lung (LLL) cavity with an air-fluid level; a smaller, more medial cavity; and some lung parenchymal opacities. Acid-fast organisms were detected in the patient's sputum, and the culture results indicated the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

-

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window setting, in a patient with treated postprimary cavitary tuberculosis who had persistent hemoptysis. This scan shows a right-upper lung cavity with a dependent mass within the cavity and air around it. This is the so-called crescent sign, which is a characteristic finding for a mycetoma, usually an aspergilloma.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in an 83-year-old woman who was sent to the emergency department from her nursing home because of a recent history of productive cough, weight loss, and fatigue. Until recently, the woman was the social director at the nursing home. In her younger years, the patient had tuberculosis during her first pregnancy; this illness occurred before antibiotic therapy was used to treat tuberculosis. This image demonstrates extensive bilateral lung nodules and a cavity in a partially collapsed right upper lung. Sputum cultures were positive for tuberculosis. The nodules indicate endobronchial spread of the tuberculosis.

-

Selective bronchial arteriogram in a patient with history of tuberculosis who presented with massive hemoptysis. This image reveals a Rasmussen aneurysm (left) that was embolized (right).

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 31-year-old man with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and a previous history of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). The patient developed shortness of breath, high-grade fever, and generalized lymphadenopathy. This image shows right mediastinal adenopathy and bilateral, uniformly tiny nodules. The man underwent biopsy by means of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), with the resultant diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis.

-

Computed tomography scan, pulmonary window, from a patient with postprimary tuberculosis. This image shows a miliary tuberculous pattern. Used with permission (Amorosa, 1999).

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph from a young female patient who presented with a cough, positive findings on skin testing with purified protein derivative of tuberculin (PPD), and a pleural effusion that was positive for acid-fast bacilli. This image shows a left pleural effusion and left lower-lobe consolidation.