Practice Essentials

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is commonly encountered in pediatric practice and is the most common gastrointestinal disease in infants (incidence rate, 1.56 per 1000 live births). [1] HPS usually presents at 2-12 weeks after birth, often in a previously healthy infant, with peak onset at week 5. The typical infant presents with nonbilious projectile vomiting and dehydration (with hypochloremic hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis) if the diagnosis is delayed. The presentation age of preterm infants is defined less clearly. Studies suggest that preterm infants may present with HPS symptoms at a later chronological age than term infants. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Stark et al reported a series of 2466 newborns with HPS, 208 (8.43%) of whom were premature. Chronological age at presentation was found generally to increase as gestational age decreased. Preterm birth was associated with longer interval from birth to presentation with HPS (median [IQR] days of 40 [30-56] vs. 33 [26–45] in full-term infants; P< 0.001). [7] HPS occurs in infants usually in the first 2 months of life and is rare in infants older than 6 months. [8, 9]

This condition accounts for one third of nonbilious vomiting occurrences in infants and is the most common reason for laparotomy before age 1 year. [10] A striking male preponderance is seen, with a male-to-female ratio of 4-6:1. In addition, pyloric stenosis and esophageal atresia may coexist. [11, 12] HPS occurs in 2-5 per 1000 infants. While the etiology remains elusive, a multivariate cause including genetic and environmental exposures is accepted. It has a predilection for male infants, first-born infants, and those born to younger mothers. It is also associated with smoking, postnatal erythromycin administration [13] , and bottle feeding. Viral etiologies have also been postulated. [14] McAteer et al showed the association with bottle feeding to be greater in older and multiparous mothers. [15]

Approximately 300 cases of adult-onset idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis have been reported. The most common clinical symptom is abdominal distention relieved by vomiting. In adults, upper gastrointestinal barium series and upper endoscopy are used to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out possible malignant disease. [16, 17]

Midgut volvulus is part of the differential diagnosis for high intestinal obstruction; however, other conditions to be considered include malrotation, with or without midgut volvulus; antral polyps; gastric duplication; focal foveolar hyperplasia; and pylorospasm.

Anatomy

In hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, the circular muscle layer becomes thickened, which narrows the pyloric channel and elongates the pylorus. During this process, the mucosa becomes redundant and may appear hypertrophic. With elongation and thickening of the muscle, the pylorus deviates upward toward the gallbladder, which serves as a marker, because in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, the pylorus can be seen adjacent to the gallbladder and anteromedial to the right kidney. The thickened pylorus narrows the pyloric channel, resulting in gastric outlet obstruction, gastric distention, and retrograde peristalsis in the stomach.

Clinical details

In the past and with experience, [18, 19] the pyloric olive, which represents the thickened and elongated pylorus, was said to be felt by surgeons in up to 80% of patients. More recent radiologic and surgical literature indicates that the olive is felt much less frequently (23% of the time in one reported case series). A meta-analysis of 43 studies (4241 infants) with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis found a wide variance in sensitivity of palpation of the pyloric olive (10-93%). [20]

The low rate of positive palpation for the pyloric olive may be the result of several factors. Patients present at an earlier age when the olive is smaller; with earlier presentation, the incidences of dehydration, metabolic alkalosis, weight loss, and failure to thrive as manifestations of HPS decrease dramatically. [21] Consequently, infants who present at a younger age are better nourished such that abdominal wall fat may obscure palpation of the mass. In addition, the skill of palpation may become lost as more medical school graduates come to rely heavily on ultrasonography for diagnosis. [22]

A peristaltic wave through the stomach may also be observed during visual inspection of the abdomen. [23]

Imaging modalities

The preferred diagnostic test for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is a contentious topic, with a wealth of articles that discuss the cost-effectiveness and the changing face of this disease. [24, 25, 26]

The first and most important step in patient workup of suspected hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is a thorough physical examination. If the pyloric olive is felt, the patient may proceed directly to the operating room without imaging. [19] However, many surgeons are uncomfortable with this protocol because a false-positive physical examination then leads to a negative laparotomy. Therefore, ultrasonography is recommended, because its sensitivity and specificity are close to 100% for this disease. [27, 28, 29] If the clinical suspicion for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is moderate to high, ultrasonography is also recommended.

(See the images below.)

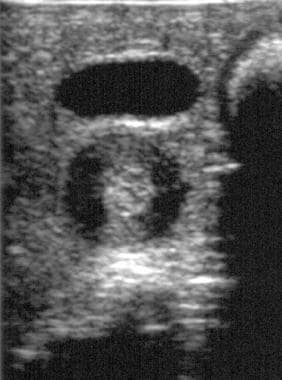

Longitudinal ultrasonogram of the pylorus in a patient with surgically proven hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Note the thickened, circular muscle, elongated pylorus, and narrowed pyloric channel.

Longitudinal ultrasonogram of the pylorus in a patient with surgically proven hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Note the thickened, circular muscle, elongated pylorus, and narrowed pyloric channel.

Transverse ultrasonographic image in a patient with proven hypertrophic pyloric stenosis demonstrates the target sign and heterogeneous echo texture of the muscular layer (the pylorus is deep to the anechoic gallbladder).

Transverse ultrasonographic image in a patient with proven hypertrophic pyloric stenosis demonstrates the target sign and heterogeneous echo texture of the muscular layer (the pylorus is deep to the anechoic gallbladder).

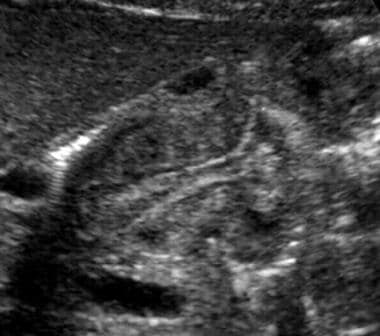

Longitudinal ultrasonogram in a patient with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis demonstrates a redundant mucosa that creates the antral nipple sign.

Longitudinal ultrasonogram in a patient with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis demonstrates a redundant mucosa that creates the antral nipple sign.

If the vomiting infant is outside the usual age range for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis or if the clinical suspicion is low, an upper GI study is recommended, because this study more effectively rules out other problems, such as malrotation and gastroesophageal reflux. [26]

(See the images below).

Some investigators have reported that a UGI study is the most cost-effective study [25] (more than ultrasonography) in the vomiting infant, because a negative ultrasonogram often leads to a UGI study to evaluate other diagnoses that a focused ultrasonographic evaluation does not detect. [26] A second test, such as ultrasonography, rarely follows a negative UGI study for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. [25, 26]

The American College of Radiology (ACR) supports abdominal ultrasonography as the initial imaging for suspected hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. The ACR notes that there may be overlap in findings between patients with pylorospasm and patients with evolving HPS. Imaging should be repeated over a period of time to ensure the correct diagnosis of HPS. [30]

In experienced hands, ultrasonography is the preferred modality in the workup of any vomiting infant. The technique includes feeding glucose water to the baby, which often improves visualization of the pylorus and, in the case of a negative study, allows continuous observation of the gastroesophageal junction to diagnose reflux. The radiologist's skill and clinical suspicion ultimately determine which test is appropriate.

Limitations of technique

Ultrasonography has high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy in the diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. However, errors in diagnosis do occur and relate to false negatives and false positives

False negatives may result from operator inexperience, in which the pylorus may not be identified. Another cause may be from distended fluid and a gas-filled stomach. These cause the pylorus to fold backward on itself such that it may remain hidden behind the stomach. The overdistended antrum may be mistaken for the pylorus; in such cases and in any infant whose pylorus is not visualized on ultrasonogram, one should place a nasogastric tube and withdraw the gastric secretions.

Muscle thickness increases with patient size, and borderline measurements are seen early in the disease and with premature infants, which may also cause false-negative findings. Some authors report an increase in muscle thickness with fluid resuscitation. [31] Observation and repeat ultrasound examination in 2-3 days can confirm the diagnosis if the patient is stable.

False positives may result from pylorospasm, a dynamic process that changes over time. The normal pylorus opens at least once every 15 minutes. The thickened muscle and elongated pylorus should be fixed. In addition, the postoperative appearance of the pylorus can lead to false-positive findings. Symptoms may take time to clear and, therefore, so do the abnormalities on ultrasonography. This modality may show hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (thickened muscle thickness) for up to 12 weeks following pyloromyotomy. In these cases, a UGI study may provide more information than ultrasonography in the evaluation of incomplete myotomy.

Special concerns

The following are issues that may arise when managing a child with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis:

-

Failure to choose the best test, which is dictated by patient history, physical examination, and the surgeon's level of suspicion.

-

Failure to choose the best radiologic investigation for the vomiting infant. If imaging is requested despite a child having a palpable pyloric olive, confirm hypertrophic pyloric stenosis by ultrasonography.

-

If the clinical history suggests hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and the child is stable, perform ultrasonography to diagnose or exclude this condition. If the ultrasonographic findings are negative, perform a UGI study to confirm or rule out other pathology.

-

Ultrasonography, although reliable for diagnosing hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, may miss malrotation, which is the most serious cause of vomiting in infants. These children require a UGI examination. Thus, if concern exists about malrotation, with or without volvulus (no olive is felt; patient is sick), a UGI study is necessary.

Radiography

Abdominal radiographs may show a fluid-filled or air-distended stomach, suggesting the presence of gastric outlet obstruction. A markedly dilated stomach with exaggerated incisura (caterpillar sign) may be seen, which represents increased gastric peristalsis in these patients (see the image below). [32] This peristaltic wave may be seen on visual inspection of the abdomen. [23] If the patient has recently vomited or has a nasogastric tube in place, the stomach is decompressed and the radiographic findings are normal.

Supine radiograph in an infant with vomiting demonstrates the caterpillar sign of active gastric hyperperistalsis.

Supine radiograph in an infant with vomiting demonstrates the caterpillar sign of active gastric hyperperistalsis.

A UGI study was once considered the test of choice for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Findings on UGI studies include the following:

-

Delayed gastric emptying (if severe, this may prevent barium from passing into the pylorus and severely limit the study)

-

Cephalic orientation of the pylorus

-

Shouldering (ie, filling defect at the antrum created by prolapse of the hypertrophic muscle)

-

Mushroom or umbrella sign (ie, thickened muscle that indents the duodenal bulb; the name refers to the impression made by the hypertrophic pylorus on the duodenum)

-

String sign (ie, barium passing through the narrowed channel, creating a single, markedly attenuated, and elongated track) (see the following image)

-

Pyloric teat (ie, outpouching created by distortion of the lesser curve by the hypertrophied muscle)

-

Retained secretions and retrograde peristalsis

Plain film radiography provides a low degree of confidence in making the diagnosis of, or in ruling out, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. A UGI study has high sensitivity (>90%) and low specificity.

High intestinal obstruction can be seen with midgut volvulus, duodenal obstruction (from stenosis, duodenal web, annular pancreas), gastric outlet obstruction caused by focal foveolar hyperplasia, and eosinophilic gastroenteritis, among others. False-negative radiographs can be seen in a child who has recently vomited.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is important in the diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and has likely contributed to the changing face of the disease, because this modality results in earlier diagnosis and treatment due to the accessibility and accuracy of ultrasonography. [21] This modality is the method of choice for both the diagnosis and exclusion of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, because ultrasonography has a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 100%. [27, 28, 31, 33] Thus, ultrasonography is also recommended in patients whose disease is clinically suspected but in whom the pyloric olive cannot be felt. [19, 27, 34, 35, 36, 37]

In a study by Leaphart et al, ultrasonography confirmed hypertrophic pyloric stenosis when the pyloric muscle thickness (MT) was greater than 4 mm and the pyloric channel length (CL) was greater than 15 mm. [38] The investigators studied the diagnostic criteria for this disease in newborns younger than 21 days and found that ultrasonographic measurement of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis was significantly decreased in younger patients (MT, 3.7 +/- 0.65 mm; CL, 16.9 +/- 2.8 mm) versus older newborns (MT, 4.6 +/- 0.82 mm; CL, 18.2 +/- 3.4 mm). Of important note, the mean ultrasonographic measurement for young newborns with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis typically fell within the range currently defined as normal or borderline. [38] A linear relationship existed between pyloric MT and CL and patient age, suggesting that 3.5 mm MT be considered the cutoff in younger patients. [38]

The ACR has noted the following in its recommendations for the diagnosis of HPS [30] :

-

US of the abdomen (UGI tract) is usually appropriate for the initial imaging of an infant older than 2 wk and up to 3 mo with new-onset nonbilious vomiting (suspected HPS).

-

US is highly accurate for diagnosing HPS, with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 100%.

-

US allows real-time imaging of the pyloric muscle and channel.

-

The diagnosis of HPS is based on imaging of a constant elongated, thick-walled pylorus with no passage of gastric content and is supported by measurements of pyloric channel length and muscle thickness.

-

Muscle thickness ≥4 mm with a length >18 mm is considered positive for HPS, but measurements between 3 and 4 mm may also be positive, particularly in the premature or younger neonate.

-

Muscle thickness measurement may be obtained on transverse or longitudinal views of the pylorus. In some patients, there is overlap of these measurements, most notably between patients with pylorospasm and patients with evolving HPS. Pylorospasm is considered to be the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in this age group and is treated conservatively.

In a retrospective study by Piotto et al of 607 patients (615 scans) who underwent ultrasonography testing for HPS, muscle thickness in the normal group was less than 2 mm, versus 2-5 mm in infants with HPS; pyloric canal length in the normal group was less than 5 mm, versus 10-24 mm in those with HPS; and transverse diameters ranged from 6 to 11 mm in the normal group, versus 8-16 mm in the HPS patients. The authors suggested that the commonly used measurement of 16 mm is too long for canal length and should be reduced to 10 mm. They also noted that muscle thickness in infants with HPS can be as low as 2 mm, versus the current standard of 3 mm. [39]

A study by Park et al of infants (< 90 days) who were brought to the ED for vomiting and underwent point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) showed that POCUS had a sensitivity of 96.6% and a specificity of 94.0% for HPS. [40]

Technique

Ultrasonography is performed with a 7.5- to 13.5-MHz linear transducer in the supine child. Transverse images at the epigastrium identify the pylorus to the left of the gallbladder and anteromedial to the right kidney (see the image below). A distended stomach, however, displaces and distorts the pylorus and may require the placement of a nasogastric tube to withdraw the stomach's contents. A gastric aspirate of more than 5 mL in a baby who has been without oral intake (NPO) for several hours indicates gastric outlet obstruction. Right posterior oblique positioning and scanning from a posterior approach may help improve visualization of the pylorus. [41]

Ultrasonographic signs of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, originally described in 1977 [42] and further defined, are as follows:

-

An MT (serosa to mucosa) greater than 3 mm (a correlation between MT and the patient's age exists; the most reliable ultrasonographic sign is an MT greater than 3 mm. Because this measurement can be increased falsely with off-axis imaging, attention to technique is important.)

-

Pyloric channel length greater than 17 mm

-

Pyloric thickness (serosa to serosa) of 15 mm or greater

-

Failure of the channel to open during a minimum of 15 minutes of scanning

-

Retrograde or hyperperistaltic contractions

-

Antral nipple sign [43] (ie, a prolapse of redundant mucosa into the antrum, which creates a pseudomass) (see the image below)

-

Other findings include reversible portal venous gas; nonuniform echogenicity of the pyloric muscle

Degree of confidence

A positive hypertrophic pyloric stenosis finding by ultrasonography almost always indicates this condition is present. A negative examination can be false in a patient who is seen early in the disease or in a younger patient whose MT is less than 3 mm.

Many articles since Teele and Smith’s original description of the ultrasound diagnosis of HPS have justified measurement criteria based on each group’s specificity, sensitivity, and positive predictive value. Values reported in the literature range from an MT of 2.5 to 4 mm or thicker and a CL of 14 to 19 mm. The risk of a false-positive test may result in a negative laparotomy. Forman concluded that an MT of 4 mm and a CL of 16-20 mm may decrease sensitivity for HPS, but these thresholds avoid a negative laparotomy. [46] The authors commented that a patient with a normal ultrasound, based on these criteria, and persistent symptoms may be reevaluated. Of note, as discussed above, younger infants may have relatively smaller measurements of the pylorus in the setting of HPS.

False positives/negatives

The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is high. Sensitivity and specificity approach 100%. [27, 28] Possible sources of false negatives are an overdistended stomach (the pylorus is hidden behind the antrum), failure to identify the pylorus (eg, operator inexperience in performing ultrasonography for evaluation of this condition), and a small infant or early presentation.

Iqbal et al showed that age and weight correlate positively with ultrasound measurement of the pylorus in pyloric stenosis and that it did not affect the diagnostic criteria. In their series of 318 ultrasound studies, there was 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity for HPS when either the pyloric channel thickness or length of 3 mm and 15 mm, respectively, were met. Further, they demonstrated a negative correlation between pyloric measurement, age, and weight when the pylorus was normal. [47] If a question remains, follow-up ultrasound can be performed in a few days to reassess muscle thickness.

Another possible source for false-positive findings is pylorospasm (typically transient). In this scenario, one should wait up to 15 minutes and remeasure the muscle to avoid mistaking muscle spasm for hypertrophy.

Although a false-negative clinical diagnosis causes diagnostic delay, a false-positive diagnosis results in a negative laparotomy. Therefore, imaging has become more important in the diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

-

Longitudinal ultrasonogram of the pylorus in a patient with surgically proven hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Note the thickened, circular muscle, elongated pylorus, and narrowed pyloric channel.

-

Transverse ultrasonographic image in a patient with proven hypertrophic pyloric stenosis demonstrates the target sign and heterogeneous echo texture of the muscular layer (the pylorus is deep to the anechoic gallbladder).

-

Longitudinal ultrasonogram in a patient with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis demonstrates a redundant mucosa that creates the antral nipple sign.

-

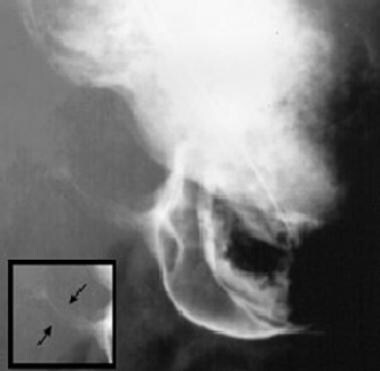

Lateral view from an upper gastrointestinal study demonstrates the double-track sign.

-

Upper gastrointestinal study from a child shows the string sign (see inset).

-

Supine radiograph in an infant with vomiting demonstrates the caterpillar sign of active gastric hyperperistalsis.